MASARYK UNIVERSITY Faculty of Social Studies Department Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Czechoslovak Exiles and Anti-Semitism in Occupied Europe During the Second World War

WALKING ON EGG-SHELLS: THE CZECHOSLOVAK EXILES AND ANTI-SEMITISM IN OCCUPIED EUROPE DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR JAN LÁNÍČEK In late June 1942, at the peak of the deportations of the Czech and Slovak Jews from the Protectorate and Slovakia to ghettos and death camps, Josef Kodíček addressed the issue of Nazi anti-Semitism over the air waves of the Czechoslovak BBC Service in London: “It is obvious that Nazi anti-Semitism which originally was only a coldly calculated weapon of agitation, has in the course of time become complete madness, an attempt to throw the guilt for all the unhappiness into which Hitler has led the world on to someone visible and powerless.”2 Wartime BBC broadcasts from Britain to occupied Europe should not be viewed as normal radio speeches commenting on events of the war.3 The radio waves were one of the “other” weapons of the war — a tactical propaganda weapon to support the ideology and politics of each side in the conflict, with the intention of influencing the population living under Nazi rule as well as in the Allied countries. Nazi anti-Jewish policies were an inseparable part of that conflict because the destruction of European Jewry was one of the main objectives of the Nazi political and military campaign.4 This, however, does not mean that the Allies ascribed the same importance to the persecution of Jews as did the Nazis and thus the BBC’s broadcasting of information about the massacres needs to be seen in relation to the propaganda aims of the 1 This article was written as part of the grant project GAČR 13–15989P “The Czechs, Slovaks and Jews: Together but Apart, 1938–1989.” An earlier version of this article was published as Jan Láníček, “The Czechoslovak Service of the BBC and the Jews during World War II,” in Yad Vashem Studies, Vol. -

Ivo PEJČOCH, Fašismus V Českých Zemích. Fašistické A

CENTRAL EUROPEAN PAPERS 2014 / II / 1 203 Ivo PEJČOCH Fašismus v českých zemích. Fašistické a nacionálněsocialistické strany a hnutí v Čechách a na Moravě 1922–1945 Praha: Academia 2011, 864 pages ISBN 978-80-200-1919-6 Critical review of Ivo Pejčoch’s book “Fascism in Czech countries. Fascist and national-so- cialist parties and movements in Bohemia and Moravia 1922-1945” The peer reviewed book written by Ivo Pejčoch, a historian working in the Military Historical Institute, was published by the Academia publishing house in 2011. The central topic of the monograph is, as the name suggests, mapping of the Czech fascism from the time of its origination in early 1920s through the period of Munich agreement and World War II to the year 1945. As the author mentions in preface, he restricts himself to the activity of organizations of Czech nation and language, due to extent limitation. The topic of the book picks up the threads of the earlier published monographs by Tomáš Pasák and Milan Nakonečný. But unlike Pasák’s book “Czech fascism 1922-1945 and col- laboration”, Ivo Pejčoch does not analyze fascism and seek causes of sympathies of a num- ber of important personalities to that ideology. On the contrary, his book rather presents a summary of parties, small parties and movements related to fascism and National Social- ism. He deals in more detail with the major ones - i.e. the Národní obec fašistická (National Fascist Community) or Vlajka (The Flag), but also for example the Kuratorium pro výchovu mládeže (Board for Youth Education) that was not a political party but, under the guid- ance of Emanuel Moravec, aimed at spreading the Roman-Empire ideas and influencing a large group of primarily young Protectorate inhabitants. -

CM 2-10.Indd

czech music quarterly Jan Mikušek The Bartered Bride Jazz of the 50s and 60s 2 0 1 0 2 | CM 2-10 obálka strany.indd 1 21.6.2010 14:51:46 International Music Festival Radio Autumn 12|10>16|10>2010 www.radioautumn.cz 12| 10| Tue 7.30 pm| Rudolfi num - Dvořák Hall 15| 10| Fri 7.30 pm| Bethlehem Chapel PRAGUE PREMIERS Contemporary Music Showcase Ferenc Liszt Concert of Laureates of Concertino Praga International Music Competition 2010 Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 14| 10| Thu 7.30 pm| Martinů Hall Fryderik Chopin | Piano Concerto No. 2 Antonín Rejcha | Overture in D Major Béla Bartók Antonio Vivaldi | Guitar concerto Pavel Zemek (Novák) Dance Suite for orchestra Johann Sebastian Bach Concerto (Consonance) for Cello and Chamber Orchestra Maurice Ravel | La Valse Violin concerto in A minorr Wojciech Widłak | Shortly „on Line“ Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Aleksander Nowak PRAGUE RADIO SYMPHONY Piano Concerto No. 23 Dark Haired Girl in a Black Sports Car ORCHESTRA Joseph Haydn | Symphony No. 45 „Farewell“ Tomáš Netopil | conductor Raminta Šerkšnytė Fairy Tale about the Little Prince Alexander Ghindin | piano COLLEGIUM OF PRAGUE RADIO SYMPHONY PLAYERS Erkki-Sven Tüür | Symphony No. 8 Tickets prices Alfonso Scarano | conductor 690, 490, 290, 90 CZK Veronika Hrdová | guitar CZECH CHAMBER PHILHARMONIC Julie Svěcená | violins ORCHESTRA PARDUBICE 13| 10| Wed 7.30 pm| Rudolfi num - Dvořák Hall Anastasia Vorotnaya | piano Marko Ivanovič | conductor Tickets prices Tickets prices Bedřich Smetana 290, 190, 90 CZK 150, 100 CZK Šárka, symphonic poem Witold Lutoslawski | Cello concerto 16| 10| Sat 7.00 pm| Rudolfi num - Dvořák Hall 15| 10| Fri 7.00 pm| Martinů Hall Zygmunt Noskowski Wojciech Kilar | Orawa for string orchestra Eye of the Sea, symphonic poem Wojciech Kilar Ignacy Jan Paderewski Leoš Janáček Ricordanza for string orcherstra Piano Concerto in A Minor Taras Bulba, rhapsody for orchestra Anatolius Šenderovas Antonín Dvořák | Symphony No. -

Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938–1948

21 Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938 –1948 LUCIE ZADRAILOVÁ AND MILAN PECH 332 Lucie Zadražilová and Milan Pech Lucie Zadražilová (Skřivánková) is a curator at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, while Milan Pech is a researcher at the Institute of Christian Art at Charles University in Prague. Teir text is a detailed archival study of the activities of two Czech art institutions, the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague and the Mánes Association of Fine Artists, during the Nazi Protectorate era and its immediate aftermath. Te larger aim is to reveal that Czech cultural life was hardly dormant during the Protectorate, and to trace how Czech institutions negotiated the limitations, dangers, and interferences presented by the occupation. Te Museum of Decorative Arts cautiously continued its independent activities and provided otherwise unattainable artistic information by keeping its library open. Te Mánes Association of Fine Artists trod a similarly-careful path of independence, managing to avoid hosting exhibitions by representatives of Fascism and surreptitiously presenting modern art under the cover of traditionally- themed exhibitions. Tis essay frst appeared in the collection Konec avantgardy? Od Mnichovské dohody ke komunistickému převratu (End of the Avant-Garde? From the Munich Agreement to the Communist Takeover) in 2011.1 (JO) Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938–1948 In the light of new information gained from archival sources and contemporaneous documents it is becoming ever clearer that the years of the Protectorate were far from a time of cultural vacuum. Credit for this is due to, among other things, the endeavours of many people to maintain at least a partial continuity in public services and to achieve as much as possible within the framework of the rules set by the Nazi occupiers. -

Český Jazz 1955- Foto Studio 5 – Karel Velebný-Ts, Vib; Jan Konopásek-Fl

Český jazz 1955- foto Studio 5 – Karel Velebný-ts, vib; Jan Konopásek-fl, bs; Artur Hollitzer-vtb; Vladimír Tomek-g; Luděk Hulan-b; Ivan Dominák-dr Zleva: Velebný, Hollitzer, Tomek, Dominák, Konopásek, Hulan Zleva: Konopásek, Hulan, Hollitzer, Tomek, Velebný, Dominák Malá EP deska, ale naše! Ukázka anonymního „obalu“: To na export se vývozní společnost Artia jinak snažila: I zadní strana obalu byla potištěna „k věci“: Tento exportní obal velké vinylové LP desky… …pak převzala vzorná brněnská reediční značka Indies Happy Trail na první CD Studia 5: Antologie Českoslovenští jazzoví sólisté (1964; nalezena jen exportní verze v angličtině) Karel Velebný kdysi Jan Konopásek současný Milan Pilar (výřez ze svatebního foto) Pavel Staněk na návštěvě u Karla Velebného (1964; autor Jan D.) Jedno z pozdějších obsazení SHQ: Rudolf Ticháček, Karel Velebný, Josef Vejvoda, Petr Kořínek. Karel Růžička Malá obměna: nahoře Růžička, Jiří Tomek-perc, Vejvoda; dole Kořínek, Velebný, Ticháček Titíž na pódiu Nahoře: František Uhlíř, Milan Vitoch, Emil Viklický. Dole: Karel Velebný, Tony Viktora Poslední Velebného spoluhráči, Uhlíř a Viklický, mezi nimi jeden dávný, Laco Tropp Metronom – Ivo Preiss-tp, Zdeněk Pulec-tb Metronom Czech jazz combo, active 1961–1965. Members: Ivo Preis (trumpet), Miroslav Rücker or Miroslav Krýsl (saxophone), Zdeněk Pulec (trombone), Vítězslav Voborník (piano), Rudolf Dašek (guitar), Jan Arnet or Vladimír Hora (double bass), Karel Turnovský (drums). Zdeněk Pulec Gustav Brom Na jaře a v létě roku 1960 měl Orchestr Gustava Broma vzácného hosta – Edmonda Halla Orchestr Gustava Broma, jak ho neznáme – na Špilberku roku 1968 pro album SABA/MPS Ještě novější foto na stadionu Zbrojovky Brno „Jen si blbněte“, myslí si asi pan kapelník. -

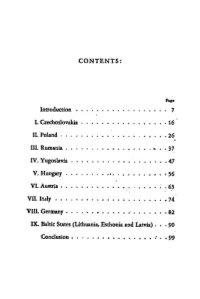

GIPE-011912-05.Pdf

CONTENTS: Paco Introduction • • . 7 L Czechoslovakia . .J6 II. Poland .. • • 26 III. Rumania . ... • 37 IV. Yugoslavia . • • • •••• 47 V. Hungary ..• • • "'.. • "' • • • • . • , " l 56 VL Austtia ••. • • • • • ; • 6_5 VII. Italy ••• • ••• 74 VIII. Germany ••.•• •· • • • • 82 IX. Baltic States (Lithuania, Esthonia and latvia) . • • 90 Conclusion • • · . • • • • • • • , • • • • : • • 99 THE MILITARY J.MPORTANCE OF. CZECHOSLOVAKIA .IN EUROPE THE MILITARY IMPORTANCE OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA IN EUROPE COLONEL EMANUEL MORAVEC Profusor of tAe HigA Sclaool of War WitL. 8 Maps t 9 s a "Orl:.is" Printing and Pul:.lisl:.iog Co., Pregue l'BilfTBD BY «OABIB# l'B.A.GVlll li:II CZJtCHOBLOVA:&:IA. "If suc(.II!SS be achieved in uniting Austria with Germany, the collapse of Czechoslovakia will follow; Germany will then have common frontiers with Italy and Yugoslavia, and Italy will be strengthened against France." Ewald Banse in "Raum und Volk im Welt kriege", Edition of 1932. I BRIEF HISTORICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL OUTLINE The Rise of the Czechoslovak State After the defeat of the Central Powers at the end of October 1918 the Austro-Hungarian Empire fell asunder. The nations that had composed it either joined their kinsmen among the victorious Allied countries-Italy, Rumania and Yugoslavia--or formed new States. In this latter ma:nner arose Czechoslo vakia and Poland. Finally, there remained the racial· remnants of the old Monarchy-Austria with a Ger man population, and Hungary with a Magyar popu lation. The territories of the new Austria and Hun gary formed a central nationality zone in Central Europe touching the Italians on the West and the Ru manians on the East. North of this German-Magyar zone were the Slavonic nations forming the Republics· of Czechoslovakia and Poland. -

Kompoziční Činnost Karla Velebného

janáčkova akademie múzických umění v brně hudební fakulta katedra jazzové interpretace studijní obor - klavír Kompoziční činnost Karla Velebného Bakalářská práce Autor práce: Bc. Augustin Bernard Vedoucí práce: MgA. Jan Dalecký Oponent práce: RNDr. Matúš Jakabčic Brno 2017 Obsah Úvod 7 1 Stav bádání 8 2 Osobnost Karla Velebného a její šíře 11 2.1 Pedagogická činnost . 12 2.2 Organizační činnost . 14 2.3 Jára da Cimrman a Dr. Evžen Hedvábný . 14 3 Kompoziční činnost Karla Velebného 17 3.1 Studio 5 . 17 3.2 SHQ . 18 3.3 Spolupráce s Orchestrem Gustava Broma . 22 3.4 Analýza vybraných kompozic . 23 3.4.1 Metodika výběru kompozic . 23 3.4.2 Skladby z období spolupráce se Studiem 5 . 23 3.4.3 Skladby z archivu Českého rozhlasu Brno . 28 3.4.4 Klarinetový koncert . 39 3.5 Shrnutí analyzovaného materiálu . 40 4 Závěr 41 5 Odkazy 42 6 Literatura 43 7 Karel Velebný v článcích a časopisech 45 8 Přílohy 51 Bibliografický záznam BERNARD, Augustin. Kompoziční činnost Karla Velebného [Compositional work of Karel Velebný]. Brno: Janáčkova akademie múzických umění v Brně, Hu- dební fakulta, Katedra jazzové interpretace, 2017. 96 s. Vedoucí práce MgA. Jan Dalecký. Anotace Bakalářská práce „Kompoziční činnost Karla Velebného“ pojednává o kompo- ziční činnosti významného českého jazzového hudebníka Karla Velebného. První část popisuje jeho osobnost z hlediska činností, kterými se ve svém životě zabý- val. Druhá část práce se na něj zaměřuje jako na skladatele. Velký prostor je zde věnován analýze výběru několika skladeb, na nichž autor zkoumá skladatelský přínos Karla Velebného české jazzové hudbě. Skladby jsou vybrány s ohledem na jeho spolupráci s Orchestrem Gustava Broma v rámci nahrávek Československého rozhlasu Brno. -

Instructions for Authors

Journal of Science and Arts Supplement at No. 2(13), pp. 157-161, 2010 THE CLARINET IN THE CHAMBER MUSIC OF THE 20TH CENTURY FELIX CONSTANTIN GOLDBACH Valahia University of Targoviste, Faculty of Science and Arts, Arts Department, 130024, Targoviste, Romania Abstract. The beginning of the 20th century lay under the sign of the economic crises, caused by the great World Wars. Along with them came state reorganizations and political divisions. The most cruel realism, of the unimaginable disasters, culminating with the nuclear bombs, replaced, to a significant extent, the European romanticism and affected the cultural environment, modifying viewpoints, ideals, spiritual and philosophical values, artistic domains. The art of the sounds developed, being supported as well by the multiple possibilities of recording and world distribution, generated by the inventions of this epoch, an excessively technical one, the most important ones being the cinema, the radio, the television and the recordings – electronic or on tape – of the creations and interpretations. Keywords: chamber music of the 20th century, musical styles, cultural tradition. 1. INTRODUCTION Despite all the vicissitudes, music continued to ennoble the human souls. The study of the instruments’ construction features, of the concert halls, the investigation of the sound and the quality of the recordings supported the formation of a series of high-quality performers and the attainment of high performance levels. The international contests organized on instruments led to a selection of the values of the interpretative art. So, the exceptional professional players are no longer rarities. 2. DISCUSSIONS The economic development of the United States of America after the two World Wars, the cultural continuity in countries with tradition, such as England and France, the fast restoration of the West European states, including Germany, represented conditions that allowed the flourishing of musical education. -

Supraphon Classical Music Catalogue 2019

s cla ssical music cat alogue 2020 Pavel Haas Quarte t 2 # Gramophone Award, 2007 # BBC Music Magazine Award, 2007 # BBC Radio 3 Disc of the Week, 2006 # Supersonic Award of Pizzicato, 2006 SU 3877-2 # BBC Music Magazine Chamber Choice, 2008 # BBC Radio 3 Disc of the Week, 2007 # Gramophone Editor’s Choice, 2008 # Cannes Classical Award, MIDEM 2009 SU 3922-2 # Gramophone Disc of the Month, 2010 # BBC Radio 3 Disc of the Week, 2010 # Caecilia, 2010 # Diapason d’Or de l’Année, 2010 # Choc de Classica, 2011 SU 3957-2 # Gramophone Award, Recording of the Year, 2011 # BBC Music Magazine Disc of the Month, 2010 # Sunday Times Album of the Week, 2010 # ClassicsToday Disc of the Month, 2011 SU 4038-2/1 # Gramophone Award, 2014 SU 4110-2 # Gramophone Award, 2015 # BBC Music Magazine Award, 2016 # Presto Classical Recordings of the Year, 2016 # Sinfini Best Chamber Album of the Year, 2015 # BBC Radio 3 Disc of the Week, 2015 # MusicWeb International Recording of the Month, 2015 SU 4172-2/1 SU 3877-2 SU 3922-2 SU 3957-2 SU 4038-2/1 # Gramophone Award, 2018 # Presto Classical Recordings of the Year, 2017 # Gramophone Editor’s Choice, 2017 # BBC Music Magazine Disc of the Month, 2017 # Sunday Times Album of the Week, 2017 # Diapason d’Or, 2018 SU 4195-2/1 # Presto Classical Recording of the Week, 2019 # Europadisc Disc of the Week, 2019 # The Times 100 Best Records of the Year, 2019 SU 4110-2 SU 4172-2/1 SU 4195-2/1 SU 4271-2 SU 4271-2 tomáš NetoPil co ndu ctor 3 You hear everything and yet not a single note obtrudes. -

Gustav Brom 100 Let

TIC BRNO ← TIC BRNO ↓ GO TO BRNO.cz Gustav Brom 100 let První angažmá Ideový koncept projektu Gustav Brom 100: Mgr. Vladimír Koudelka Archivní fotografie: archiv ČT, Jef Kratochvil, archiv Českého rozhlasu Brno Současné fotografie: Michal Růžička, Gustav Brom se na vlastní nohy postavil Tam si na ni ale úřady přece jen došláply později vyrostl v jednu z největších osob- Pocket Media s.r.o., Igor Zehl poměrně záhy. Ještě v roce 1940, konkrét- a Gustav Brom se tak opět ocitl se želízky ností historie českého jazzu. Samotný ně 15. června, získal se svými R-Boys první na rukou. Naštěstí byl mezi příznivci kapely Brom pak hrál nejen na altsaxofon, klari- TIC BRNO, p. o. finančně podporuje angažmá, a to v hotelu Radhošť v Rožno- i jeden ze zaměstnanců brněnského úřadu net a housle, ale příležitostně přidal i zpěv statutární město Brno. vě pod Radhoštěm. V Brně začala kapela práce, k terý muzikantům zajistil místo v br- a nebál se chopit ani kontrabasu. Ještě za 2021 pravidelně koncertovat v hotelu Passage něnské Zbrojovce. Režim se nažral, kapela války se orchestr z kavárenské kapely vy- na Lidické ulici a dařilo se jí natolik, že si zůstala celá a mohla dál koncertovat. pracoval na koncertní a rozhlasové těleso. www.gustavbrom100.cz Brom opatřil živnostenský list jako kapelník. První spolupráci s rozhlasem navázal v roce Jenže režim by zdatné mladíky viděl raději Obsazení kapely se z původních šesti čle- 1942, kdy mu brněnská stanice vyhradila www.ticbrno.cz bojovat na válečné frontě než swingovat nů během války postupně zdvojnásobilo. každou středu odpoledne půlhodinu pří- na pódiu. -

Spis Treci 1.Indd

Zeszyty Naukowe ASzWoj nr 2(111) 2018 War Studies University Scientific Quarterly no. 2(111) 2018 ISSN 2543-6937 THE DEFENCE SECTOR AND ITS EFFECT ON NATIONAL SECURITY DURING THE CZECHOSLOVAK (MUNICH) CRISIS 1938 Aleš BINAR, PhD University of Defence in Brno Abstract The Czechoslovak (Munich) Crisis of 1938 was concluded by an international conference that took place in Munich on 29-30 September 1938. The decision of the participating powers, i.e. France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom, was made without any respect for Czechoslovakia and its representatives. The aim of this paper is to examine the role of the defence sector, i.e. the representatives of the ministry of defence and the Czechoslovak armed forces during the Czechoslovak (Munich) Crisis in the period from mid-March to the beginning of October 1938. There is also a question as to, whether there are similarities between the position then and the present-day position of the army in the decision-making process. Key words: Czechoslovak (Munich) Crisis, Munich Agreement, 1938, Czechoslovak Army, national security. Introduction The agreement in Munich (München), where the international conference took place on 29–30 September 1938, represents a crucial crossroads in the history of Czechoslovakia. By accepting the Munich Agreement, Czechoslovak President, Edvard Beneš, and representatives of his government made a decision that affected the nation not only for the next few years, but for decades thereafter. This so-called Munich Syndrome, then, is infamously blamed by many in Czechoslovak society for the fascist-like orientation of the so-called the Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–1939) and the acceptance of the Communist coup d’état of 1948. -

Šéfredaktor Protektorátní Přítomnosti E

Masarykova univerzita Fakulta sociálních studií Šéfredaktor protektorátní Přítomnosti E. Vajtauer před Národním soudem E. Vajtauer, the editor in chief of protectorate „Přítomnost“, on the National court Diplomová práce Bc. Kristýna Maletová Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Pavel Večeřa, Ph.D. Brno 2015 Čestné prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím pramenů a literatury uvedené v bibliografii. V Brně, dne 23. 12. 2015 …………………… 2 Poděkování Na tomto místě bych ráda poděkovala především vedoucímu diplomové práce panu PhDr. Pavlu Večeřovi, Ph.D., zejména za jeho trpělivost a cenné rady, kterými mi ochotně pomáhal řešit odborné a organizační problémy této práce. Ke zdárnému dokončení mi pomohla také podpora rodiny a zejména přítele, kteří mi dodávali povzbuzení vždy, když jsem potřebovala. 3 Anotace Diplomová práce „Šéfredaktor protektorátní Přítomnosti E. Vajtauer před Národním soudem“ se zabývá životními osudy Emanuela Vajtauera (*1892 – † ?), jednoho z předních představitelů skupiny tzv. aktivistických novinářů, kteří v době okupace kolaborovali s nacistickým Německem, a pojednává o soudním procesu z dubna roku 1947, jenž proběhl v nově obnoveném Československu v rámci poválečné retribuce, kdy byli před Národní soud postaveni ti, kteří svou činností v období existence protektorátu podporovali a propagovali nacistické hnutí. Autorka v úvodu práce zasazuje téma do historického kontextu, kdy přibližuje okolnosti vzniku Protektorátu Čechy a Morava, vysvětluje tehdejší tiskové poměry a věnuje se problematice kolaborace, aktivismu a následně i poválečného retribučního soudnictví. Stěžejní částí práce je pak komplexnější zachycení Vajtauerova života a činnosti, snaha dopátrat se konkrétních motivů, jež jej vedly k této kolaborační činnosti, a rekonstrukce soudního líčení. Emanuel Vajtauer byl v době nacistické okupace jedním z prominentních aktivistických šéfredaktorů, jenž byl následně Národním soudem uznán vinným ze zločinu proti státu a odsouzen k trestu smrti provazem.