Submission to the Committee on the Rights of the Child Review of Ecuador 90Th Pre-Session July 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

She Is Not a Criminal

SHE IS NOT A CRIMINAL THE IMPACT OF IRELAND’S ABORTION LAW Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2015 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2015 Index: EUR 29/1597/2015 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Stock image: Female patient sitting on a hospital bed. © Corbis amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. Executive summary ................................................................................................... 6 -

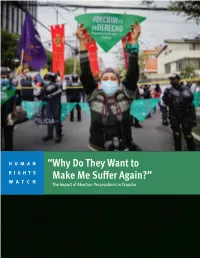

“Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” the Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador

HUMAN “Why Do They Want to RIGHTS WATCH Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ....................................................................................................... 8 To the Presidency ................................................................................................................... -

Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #Metoo

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 49 Issue 1 Article 3 2019 Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #MeToo Nicole Hallett University of Buffalo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hallett, Nicole (2019) "Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #MeToo," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 49 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol49/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMMIGRANT WOMEN IN THE SHADOW OF #METOO Nicole Hallett* I. INTRODUCTION We hear Daniela Contreras’s voice, but we do not see her face in the video in which she recounts being raped by an employer at the age of sixteen.1 In the video, one of four released by a #MeToo advocacy group, Daniela speaks in Spanish about the power dynamic that led her to remain silent about her rape: I couldn’t believe that a man would go after a little girl. That a man would take advantage because he knew I wouldn’t say a word because I couldn’t speak the language. Because he knew I needed the money. Because he felt like he had the power. And that is why I kept quiet.2 Daniela’s story is unusual, not because she is an undocumented immigrant who was victimized -

Supplementary Information on Kenya, Scheduled for Review by the Pre

Re: Supplementary Information on Kenya, Scheduled for Review by the Pre-sessional Working Group of the Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights during its 56th Session Distinguished Committee Members, This letter is intended to supplement the periodic report submitted by the government of Kenya, which is scheduled to be reviewed during the 56th pre-session of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (the Committee). The Center for Reproductive Rights (the Center) a global legal advocacy organization with headquarters in New York and, and regional offices in Nairobi, Bogotá, Kathmandu, Geneva, and Washington, D.C., hopes to further the work of the Committee by providing independent information concerning the rights protected under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR),1 and other international and regional human rights instruments which Kenya has ratified.2 The letter provides supplemental information on the following issues of concern regarding the sexual and reproductive rights of Kenyan women and girls: the high rate of preventable maternal mortality and morbidity; the abuse and mistreatment of women that attend maternal health care services; inaccessibility of safe abortion services and post-abortion care; lack of access to comprehensive family planning services and information; and discrimination resulting in gender-based violence and female genital mutilation. I. The Right to Equality and Non-Discrimination It has long been recognized that the obligation to ensure the rights -

How to Face Violence Against Women

Step by step HowEMANU to face violence against women ELA 5ªD Cambridge 0 EmanueLiceo Scientifico Statale “Gaetano Salvemini”, Bari Index Preface 1 Violence against women in the past and in the present: spot the differences 2 Women’s voices for change 9 The strange case of misogyny 16 Women: muses in art and objects in real life 22 Violence behind the screen and the musical notes 27 Two pandemics: violence against women and COVID-19 32 Rape culture: the monster in our minds 35 41 Words and bodies: verbal violence and prostitution Conclusion 45 Bibliography 46 1 Preface The idea for this book was born during an English lesson, on an apparently normal Wednesday. However, it was the 25th of November 2020, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against women, and our teacher decided to focus on something which is not included in our school programme. By exchanging our opinions, we understood that our knowledge about the issue was not deep at all, no matter how many newspapers we read or news we watch. That pushed us to start this journey through all the aspects of violence against women. We did it by dividing us into groups and doing several types of research on many different websites and books (you can find our sources on page 46). We discovered that this problem is much wider than what we expected; it has influenced our world in endless ways, affecting all the fields of knowledge, such as art, cinema and music. We ended up reading hundreds of stories that touched us very deeply; that’s how we decided to give life to these pages. -

Pregnancy from Rape Can Seem to Addition, 10.9 Percent of U.S

courages all victims from reporting rape, encourages isolation, and causes women to tive feelings and fears. Of those who continued 4 M. Planty et al., note 2. 5 their pregnancy, two-thirds developed more posi- C. Tietze, “Probability of pregnancy resulting from a single unpro- conceal signs of victimization. Because pregnan- tected coitus,” Fertility and Sterility 11: 5 (1960) 485-488. cy cannot be hidden, the mentality of blaming tive feelings toward their unborn child as the 6 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “National Survey the victim only encourages resort to abortion. pregnancy progressed. Their feelings of self- Family Growth 2006-2010,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg.htm (accessed May esteem and contentedness improved during the 14, 2013). Response to pregnancy pregnancy, while anxiety, depression, anger and 7 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “National Survey fear decreased. Family Growth 2006-2010,” note 6; Guttmacher Institute, Rape victims may respond in a variety of ways “Contraceptive Use in the United States,” http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/fb_contr_use.html (accessed May on learning they are pregnant—anger, fear, The abortion rate among rape victims (50 per- 14, 2013). anxiety, depression, complacency and anything cent) is not substantially higher than among all 8 L.B. Finer et al., “Reasons U.S. Women Have Abortions: else you can imagine. Family and friends often Quantitative and Qualitative Perspectives,” Perspectives on Sexual women who report an “unintended pregnancy” and Reproductive Health 37:3 (2005), feel helpless or are uncomfortable and embar- (40 percent).10 The majority of those who http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/3711005.html (accessed rassed. -

Case 1:17-Cv-02122-TSC Document 87-1 Filed 12/21/17 Page 1 of 8

Case 1:17-cv-02122-TSC Document 87-1 Filed 12/21/17 Page 1 of 8 Case 1:17-cv-02122-TSC Document 87-1 Filed 12/21/17 Page 2 of 8 Case 1:17-cv-02122-TSC Document 87-1 Filed 12/21/17 Page 3 of 8 Case 1:17-cv-02122-TSC Document 87-1 Filed 12/21/17 Page 4 of 8 Case 1:17-cv-02122-TSC Document 87-1 Filed 12/21/17 Page 5 of 8 NOTE TO FILE December 17, 2017 Scott Lloyd, Director Background We have in our custody an unaccompanied alien child (UAC) who is years old and who reported that she was sexually assaulted in her home country. Based on the timeframe she provided for the sexual assault, we have reason to believe that this assault resulted in her current pregnancy. While she also reported that she had a boyfriend in her home country with whom she had intercourse, the UAC also now believes she is pregnant with the child of her attacker. Several weeks after the assault, she made the journey to the United States where she attempted to cross the border illegally, but was apprehended at the border, and is now in our care. She originally requested an abortion upon confirmation that she was pregnant, but rescinded the request after she reported that her mother, and the who was to serve as her sponsor, threatened to “beat” her if she did so. She renewed her request after a few days, although language difficulties and other circumstances made it unclear that she knew what she was requesting. -

The Community Response to Rape: Victims' Experiences with the Legal, Medical, and Mental Health Systems1

American Journal of Community Psychology, Vol. 26, No. 3, 1998 The Community Response to Rape: Victims' Experiences with the Legal, Medical, and Mental Health Systems1 Rebecca Campbell2 University of Illinois at Chicago This research examined how the legal, medical, and mental health systems respond to the needs of rape victims. A national random sample of rape victim advocates (N = 168) participated in a phone interview that assessed the resources available to victims in their communities. as well as the specific experiences of the most recent rape victim with which they had completed work. Results from hierarchical and iterative cluster analysis revealed three patterns in victims' experiences with the legal, medical, and mental health systems. One group of victims had relatively positive experiences with all three systems, a second group had beneficial outcomes with only the medical systems, and the final group had difficult encounters with all three systems. Multinominal logistic regression was then used to evaluate an ecological model predicting cluster membership. Community-level factors as well as features of the assault and characteristics of the victims predicted unique variance in victims' outcomes with the legal, medical, and mental health systems. These findings provide empirical support for a basic tenet of ecological theory: environmental structures and practices influence individual outcomes. Implications for ecological theory and interventions to improve the community response to rape victims' needs are discussed. KEY WORDS: rape victims; community response; rape victim advocates. 1The author thanks Ana Mari Cauce, Bill Davidson, Chris Keys, Deborah Salem, and Sarah Ullman for their helpful comments on this paper; the members of the Community Response to Rape Project for their assistance in data collection; and the rape victim advocates who participated in this study for their time, expertise, and feedback on this manuscript. -

National Guidelines on Management of Sexual Violence in Kenya

MINISTRY OF HEALTH National Guidelines on Management of Sexual Violence in Kenya 3rd Edition, 2014 i National Guidelines on Management of Sexual Violence in Kenya 3rd Edition, 2014 Printing supported by German Development Cooperation through SGBV Networks Project Table of Contents Forward vii Acknowledgements ix Executive Summary xi Acronyms xiii Definition of Terms xv Medical Management 1 Pyscho Social Support 19 Forensic Management of Sexual Violence 29 Humanitarian Issues 39 Quality Assurance and Quality Improvement 44 Annexes 47 Forward exual Violence is a serious public health and human rights concern in Kenya. It affects men Sand women, boys and girls and has adverse physical and Psycho-social consequences on the survivor. The post election violence experienced in 2008 following the disputed 2007 presidential elections, that saw a wave of sexual abuse targeted at women and girls, was perhaps the clearest manifestation of the gravity of sexual violence in Kenya. Sexual Violence and its attendant consequences threaten the attainment of global development goals espoused in the Millennium Development Goals and national goals contained in Vision 2030 as well as the National Health Sector Strategic Plan II, as it affects the health and well being of the survivor. Of concern is the emerging evidence worldwide that Sexual Violence is an important risk factor contributing towards vulnerability to HIV infection. The National Plan for Mainstreaming Gender into the HIV/AIDS strategic plan for Kenya has identified sexual violence as an issue of concern in HIV transmission, particularly among adolescents. This calls for comprehensive measures to address issues of Sexual Violence and more importantly meet the diverse and often complex needs of the survivors and their families. -

Rape Pregnancy and My Furor Over Social Myths,” Elliot Institute

LIFE MATTERS: PREGNANCY FROM RAPE A rape victim becoming pregnant—what situation Prevalence and reporting: According to the could be more emotionally charged than that? National Crime Victimization Survey (a large household survey of over 146,000 individuals over Even among those who are pro-life, some age 12), designed to capture reported and individuals are tempted to condone aborting unreported crimes, there were 143,300 completed children conceived from rape out of a natural “rape and sexual assault victimizations” against empathy for the rape victim. Rape is an evil act. females in the U.S. in 2010. That means an assault Since pregnancy from rape can seem to compound for every 1,000 females age 12 and older. The rate and prolong the victim’s anguish, some believe that was highest among women under age 35. The great abortion will permit the rape victim to begin healing majority of victims were related to or in a earlier. relationship with their attacker. Only slightly over Abortion advocates exploit this compassion, one-third reported the attack to police. Eleven pointing endlessly to the “need” for abortion in the percent of assaults were associated with a weapon. case of pregnancy from rape. Because abortion is Injuries, ranging from gunshot wounds to minor already legal for any reason, their real purpose is to bruises and cuts, were reported by 58 percent of marginalize and malign those who are consistent in victims. Only 35 percent of those with an injury their pro-life beliefs—by characterizing them as sought treatment.4 insensitive and rigid. -

Gender Perspectives on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, Or Degrading Treatment Or Punishment: Expert Consultation

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Reports Scholarship & Research 11-5-2015 Gender Perspectives on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment: Expert Consultation Brenda V. Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/fasch_rpt Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Law and Gender Commons GENDER PERSPECTIVES ON TORTURE AND OTHER CRUEL, INHUMAN, OR DEGRADING TREATMENT OR PUNISHMENT EXPERT CONSULTATION NOVEMBER 5 – 6, 2015 WORKING PAPER1 INTRODUCTION The aim of this consultation with experts is to ensure that the Special Rapporteur receives the necessary exposure to the different practices, international standards and jurisprudence, and expert opinions that will help him draft his forthcoming thematic report for the United Nations Human Rights Council. The report will focus on assessing the unique experiences of women, girl children and LGBTI persons from the perspective of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment and punishment (“CIDTP”) in international law. The consultation will focus on specific practices where the mistreatment rises to the level of torture or CIDTP to identify gaps in protection, state obligations, and best practices. The thematic report will specifically consider practices such as, inter alia, violence and discrimination against women, girls, and LGBTI persons; conflict-related sexual violence; domestic violence; custody and detention practices; honour-based violence, human trafficking, reproductive rights and healthcare, and other cultural practices that uniquely or disproportionately affect women and LGBTI individuals. The purpose of examining these practices will be to determine whether higher or modified standards are required to ensure adequate protection of women, girls, and LGBTI persons. -

Sexual Assault Forensic Examiner Program Guidelines for the Care of the Sexual Assault Patient

SEXUAL ASSAULT FORENSIC EXAMINER PROGRAM GUIDELINES for the CARE OF THE SEXUAL ASSAULT PATIENT Sexual Assault Forensic Examiner Program Office of the Attorney General 6 State House Station Augusta, Maine 04333-0006 207-626-8806 January 2011 (Page left blank intentionally) SEXUAL ASSAULT FORENSIC EXAMINER PROGRAM The following recommendations were developed by a subcommittee of the Sexual Assault Forensic Examiner Program Advisory Board. Reviewers included Sexual Assault Forensic Examiners, emergency department physicians, sexual assault support center advocates, and prosecutors. Many thanks to all who participated in the creation of the guidelines. Committee Members Polly Campbell, RN, SAFE Program Director Barbara Covey, MD Gloria DiSalvatore, RN, ME-SANE-A Dottie MacCabe, RN, ME-SANE-A Hannah Pressler, MHS, PNP Reviewers Deb Cashman, Assistant District Attorney Carmen Columbe, Assistant Attorney General Sue Hall Dreher, Executive Director, Sexual Assault Support Services of Midcoast Maine Nancy Fishwick, PhD, FNP, Director, School of Nursing, University of Maine Kathy Greason, Assistant Attorney General Robin Matthews, RN, SANE-A Gretchen Lajoie, Forensic Chemist II, Maine State Police Crime Laboratory Mary Lake, RN, ME-SANE-A Jeanette Michaud, RN, SANE-A Melissa O‘Dea, Assistant Attorney General Pam Poisson, RN, ME-SANE-A Tina Panayides, Esq. Kathy Parent, RN, ME-SANE –A Lois Skillings, RN, CEO, Midcoast Hospital Joni Sephton, RN, ME-SANE-A Janice Stuver, Assistant Attorney General Table of Contents (Page left blank intentionally)