What Is the Difference Between a Million, Billion and Trillion?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Large but Finite

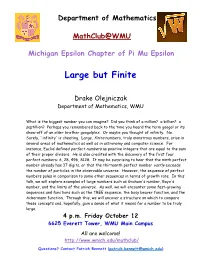

Department of Mathematics MathClub@WMU Michigan Epsilon Chapter of Pi Mu Epsilon Large but Finite Drake Olejniczak Department of Mathematics, WMU What is the biggest number you can imagine? Did you think of a million? a billion? a septillion? Perhaps you remembered back to the time you heard the term googol or its show-off of an older brother googolplex. Or maybe you thought of infinity. No. Surely, `infinity' is cheating. Large, finite numbers, truly monstrous numbers, arise in several areas of mathematics as well as in astronomy and computer science. For instance, Euclid defined perfect numbers as positive integers that are equal to the sum of their proper divisors. He is also credited with the discovery of the first four perfect numbers: 6, 28, 496, 8128. It may be surprising to hear that the ninth perfect number already has 37 digits, or that the thirteenth perfect number vastly exceeds the number of particles in the observable universe. However, the sequence of perfect numbers pales in comparison to some other sequences in terms of growth rate. In this talk, we will explore examples of large numbers such as Graham's number, Rayo's number, and the limits of the universe. As well, we will encounter some fast-growing sequences and functions such as the TREE sequence, the busy beaver function, and the Ackermann function. Through this, we will uncover a structure on which to compare these concepts and, hopefully, gain a sense of what it means for a number to be truly large. 4 p.m. Friday October 12 6625 Everett Tower, WMU Main Campus All are welcome! http://www.wmich.edu/mathclub/ Questions? Contact Patrick Bennett ([email protected]) . -

An Atomic Physics Perspective on the New Kilogram Defined by Planck's Constant

An atomic physics perspective on the new kilogram defined by Planck’s constant (Wolfgang Ketterle and Alan O. Jamison, MIT) (Manuscript submitted to Physics Today) On May 20, the kilogram will no longer be defined by the artefact in Paris, but through the definition1 of Planck’s constant h=6.626 070 15*10-34 kg m2/s. This is the result of advances in metrology: The best two measurements of h, the Watt balance and the silicon spheres, have now reached an accuracy similar to the mass drift of the ur-kilogram in Paris over 130 years. At this point, the General Conference on Weights and Measures decided to use the precisely measured numerical value of h as the definition of h, which then defines the unit of the kilogram. But how can we now explain in simple terms what exactly one kilogram is? How do fixed numerical values of h, the speed of light c and the Cs hyperfine frequency νCs define the kilogram? In this article we give a simple conceptual picture of the new kilogram and relate it to the practical realizations of the kilogram. A similar change occurred in 1983 for the definition of the meter when the speed of light was defined to be 299 792 458 m/s. Since the second was the time required for 9 192 631 770 oscillations of hyperfine radiation from a cesium atom, defining the speed of light defined the meter as the distance travelled by light in 1/9192631770 of a second, or equivalently, as 9192631770/299792458 times the wavelength of the cesium hyperfine radiation. -

Building the Bridge Between the First and Second Year Experience: a Collaborative Approach to Student Learning and Development STEP

Building the bridge between the first and second year experience: A collaborative approach to student learning and development STEP Introductions STEP Agenda for Today • Share research and theory that shapes first and second year programs • Differentiate programs, interventions, and support that should be targeted at first year students, second year students, or both • Think about your own department and how to work differently with first and second-year students • Review structure of FYE and STEP at Ohio State and where your office can support existing efforts STEP Learning Outcomes • Participants will reflect on and articulate what services, resources, and programming currently exist in their department for first and/or second year students. • Participants will articulate the key salient needs and developmental milestones that often distinguish the second year experience from the first. • Participants will be able to utilize at least one strategy for curriculum differentiation that will contribute to a more seamless experiences for students between their first and second year. Foundational Research that Informs FYE and STEP STEP Developmental Readiness and Sequencing • Developmental Readiness: “The ability and motivation to attend to, make meaning of, and appropriate new knowledge into one’s long term memory structures” (Hannah & Lester, 2009). • Sequencing: The order and structure in which people learn new skill sets (Hannah & Avolio, 2010). • Scaffolding: Support given during the learning process which is tailored to the needs of an -

Grade 7/8 Math Circles the Scale of Numbers Introduction

Faculty of Mathematics Centre for Education in Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1 Mathematics and Computing Grade 7/8 Math Circles November 21/22/23, 2017 The Scale of Numbers Introduction Last week we quickly took a look at scientific notation, which is one way we can write down really big numbers. We can also use scientific notation to write very small numbers. 1 × 103 = 1; 000 1 × 102 = 100 1 × 101 = 10 1 × 100 = 1 1 × 10−1 = 0:1 1 × 10−2 = 0:01 1 × 10−3 = 0:001 As you can see above, every time the value of the exponent decreases, the number gets smaller by a factor of 10. This pattern continues even into negative exponent values! Another way of picturing negative exponents is as a division by a positive exponent. 1 10−6 = = 0:000001 106 In this lesson we will be looking at some famous, interesting, or important small numbers, and begin slowly working our way up to the biggest numbers ever used in mathematics! Obviously we can come up with any arbitrary number that is either extremely small or extremely large, but the purpose of this lesson is to only look at numbers with some kind of mathematical or scientific significance. 1 Extremely Small Numbers 1. Zero • Zero or `0' is the number that represents nothingness. It is the number with the smallest magnitude. • Zero only began being used as a number around the year 500. Before this, ancient mathematicians struggled with the concept of `nothing' being `something'. 2. Planck's Constant This is the smallest number that we will be looking at today other than zero. -

Second Time Moms & the Truth About Parenting

Second Time Moms & The Truth About Parenting Summary Why does our case deserve an award? In the US, and globally, every diaper brand obsesses about the emotion and joy experienced by new parents. Luvs took the brave decision to focus exclusively on an audience that nobody was talking to: second time moms. Planning made Luvs the official diaper brand of experienced moms. The depth of insights Planning uncovered about this target led to creative work that did a very rare thing for the diaper category: it was funny, entertaining and sparked a record amount of debate. For the first time these moms felt that someone was finally standing up for them and Luvs was applauded for not being afraid to show motherhood in a more realistic way. And in doing so, we achieved the highest volume and value sales in the brand’s history. 2 Luvs: A Challenger Facing A Challenge Luvs is a value priced diaper brand that ranks a distant fourth in terms of value share within the US diaper category at 8.9%. Pampers and Huggies are both premium priced diapers that make up most of the category, with value share at 31, and 41 respectively. Private Label is the third biggest player with 19% value share. We needed to generate awareness to drive trial for Luvs in order to grow the brand, but a few things stood in our way. Low Share Of Voice Huggies spends $54 million on advertising and Pampers spends $48 million. In comparison, Luvs spends only $9 million in media support. So the two dominant diaper brands outspend us 9 to 1, making our goal of increased awareness very challenging. -

Second Amendment Rights

Second Amendment Rights Donald J. Trump on the Right to Keep and Bear Arms The Second Amendment to our Constitution is clear. The right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed upon. Period. The Second Amendment guarantees a fundamental right that belongs to all law-abiding Americans. The Constitution doesn’t create that right – it ensures that the government can’t take it away. Our Founding Fathers knew, and our Supreme Court has upheld, that the Second Amendment’s purpose is to guarantee our right to defend ourselves and our families. This is about self-defense, plain and simple. It’s been said that the Second Amendment is America’s first freedom. That’s because the Right to Keep and Bear Arms protects all our other rights. We are the only country in the world that has a Second Amendment. Protecting that freedom is imperative. Here’s how we will do that: Enforce The Laws On The Books We need to get serious about prosecuting violent criminals. The Obama administration’s record on that is abysmal. Violent crime in cities like Baltimore, Chicago and many others is out of control. Drug dealers and gang members are given a slap on the wrist and turned loose on the street. This needs to stop. Several years ago there was a tremendous program in Richmond, Virginia called Project Exile. It said that if a violent felon uses a gun to commit a crime, you will be prosecuted in federal court and go to prison for five years – no parole or early release. -

Accounting Recommended Four-Year Plan (Fall 2010)

Anisfield School of Business Accounting Recommended Four-Year Plan (Fall 2010) This recommended four-year plan is designed to provide a blueprint for students to complete their degrees within four years. These plans are the recommended sequences of courses. Students must meet with their Major Advisor to develop a more individualized plan to complete their degree. This plan assumes that no developmental courses are required. If developmental courses are needed, students may have additional requirements to fulfill which are not listed in the plan and degree completion may take longer. NOTE: This recommended Four-Year Plan is applicable to students admitted into the major during the 2010-2011 academic year. First Year Fall Semester HRS Spring Semester HRS GenEd: INTD 101-First Year Seminar 4 School Core: ECON 101-Microeconomics 4 GenEd: ENGL 180-College English 4 GenEd: Science w/ Experiential 4 GenEd/School Core: BADM 115-Perspectives 4 GenEd: History 4 of Business & Society GenEd: MATH 101, 110 or 121-Mathematics 4 Major: INFO 224-Principles of Information 4 Technology Total: 16 Total: 16 Second Year Fall Semester HRS Spring Semester HRS Major: ACCT 221-Principles of Financial 4 Major: ACCT 222-Principles of Managerial 4 Accounting Accounting Major: MKTG 290-Marketing Principles & 4 GenEd: AIID 201-Readings in Humanities 4 Practices Major: BADM 225-Management Statistics 4 Major: FINC 301-Corporate Finance I 4 School Core: ECON 102-Macroeconomics 4 Major: BADM 223-Business Law 1 4 Total: 16 Total: 16 Third Year Fall Semester HRS Spring -

WRITING and READING NUMBERS in ENGLISH 1. Number in English 2

WRITING AND READING NUMBERS IN ENGLISH 1. Number in English 2. Large Numbers 3. Decimals 4. Fractions 5. Power / Exponents 6. Dates 7. Important Numerical expressions 1. NUMBERS IN ENGLISH Cardinal numbers (one, two, three, etc.) are adjectives referring to quantity, and the ordinal numbers (first, second, third, etc.) refer to distribution. Number Cardinal Ordinal In numbers 1 one First 1st 2 two second 2nd 3 three third 3rd 4 four fourth 4th 5 five fifth 5th 6 six sixth 6th 7 seven seventh 7th 8 eight eighth 8th 9 nine ninth 9th 10 ten tenth 10th 11 eleven eleventh 11th 12 twelve twelfth 12th 13 thirteen thirteenth 13th 14 fourteen fourteenth 14th 15 fifteen fifteenth 15th 16 sixteen sixteenth 16th 17 seventeen seventeenth 17th 18 eighteen eighteenth 18th 19 nineteen nineteenth 19th 20 twenty twentieth 20th 21 twenty-one twenty-first 21st 22 twenty-two twenty-second 22nd 23 twenty-three twenty-third 23rd 1 24 twenty-four twenty-fourth 24th 25 twenty-five twenty-fifth 25th 26 twenty-six twenty-sixth 26th 27 twenty-seven twenty-seventh 27th 28 twenty-eight twenty-eighth 28th 29 twenty-nine twenty-ninth 29th 30 thirty thirtieth 30th st 31 thirty-one thirty-first 31 40 forty fortieth 40th 50 fifty fiftieth 50th 60 sixty sixtieth 60th th 70 seventy seventieth 70 th 80 eighty eightieth 80 90 ninety ninetieth 90th 100 one hundred hundredth 100th 500 five hundred five hundredth 500th 1,000 One/ a thousandth 1000th thousand one thousand one thousand five 1500th 1,500 five hundred, hundredth or fifteen hundred 100,000 one hundred hundred thousandth 100,000th thousand 1,000,000 one million millionth 1,000,000 ◊◊ Click on the links below to practice your numbers: http://www.manythings.org/wbg/numbers-jw.html https://www.englisch-hilfen.de/en/exercises/numbers/index.php 2 We don't normally write numbers with words, but it's possible to do this. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

Simple Statements, Large Numbers

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln MAT Exam Expository Papers Math in the Middle Institute Partnership 7-2007 Simple Statements, Large Numbers Shana Streeks University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Streeks, Shana, "Simple Statements, Large Numbers" (2007). MAT Exam Expository Papers. 41. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap/41 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Math in the Middle Institute Partnership at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAT Exam Expository Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Master of Arts in Teaching (MAT) Masters Exam Shana Streeks In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Teaching with a Specialization in the Teaching of Middle Level Mathematics in the Department of Mathematics. Gordon Woodward, Advisor July 2007 Simple Statements, Large Numbers Shana Streeks July 2007 Page 1 Streeks Simple Statements, Large Numbers Large numbers are numbers that are significantly larger than those ordinarily used in everyday life, as defined by Wikipedia (2007). Large numbers typically refer to large positive integers, or more generally, large positive real numbers, but may also be used in other contexts. Very large numbers often occur in fields such as mathematics, cosmology, and cryptography. Sometimes people refer to numbers as being “astronomically large”. However, it is easy to mathematically define numbers that are much larger than those even in astronomy. We are familiar with the large magnitudes, such as million or billion. -

1 Powers of Two

A. V. GERBESSIOTIS CS332-102 Spring 2020 Jan 24, 2020 Computer Science: Fundamentals Page 1 Handout 3 1 Powers of two Definition 1.1 (Powers of 2). The expression 2n means the multiplication of n twos. Therefore, 22 = 2 · 2 is a 4, 28 = 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 is 256, and 210 = 1024. Moreover, 21 = 2 and 20 = 1. Several times one might write 2 ∗ ∗n or 2ˆn for 2n (ˆ is the hat/caret symbol usually co-located with the numeric-6 keyboard key). Prefix Name Multiplier d deca 101 = 10 h hecto 102 = 100 3 Power Value k kilo 10 = 1000 6 0 M mega 10 2 1 9 1 G giga 10 2 2 12 4 T tera 10 2 16 P peta 1015 8 2 256 E exa 1018 210 1024 d deci 10−1 216 65536 c centi 10−2 Prefix Name Multiplier 220 1048576 m milli 10−3 Ki kibi or kilobinary 210 − 230 1073741824 m micro 10 6 Mi mebi or megabinary 220 40 n nano 10−9 Gi gibi or gigabinary 230 2 1099511627776 −12 40 250 1125899906842624 p pico 10 Ti tebi or terabinary 2 f femto 10−15 Pi pebi or petabinary 250 Figure 1: Powers of two Figure 2: SI system prefixes Figure 3: SI binary prefixes Definition 1.2 (Properties of powers). • (Multiplication.) 2m · 2n = 2m 2n = 2m+n. (Dot · optional.) • (Division.) 2m=2n = 2m−n. (The symbol = is the slash symbol) • (Exponentiation.) (2m)n = 2m·n. Example 1.1 (Approximations for 210 and 220 and 230). -

Big Numbers Tom Davis [email protected] September 21, 2011

Big Numbers Tom Davis [email protected] http://www.geometer.org/mathcircles September 21, 2011 1 Introduction The problem is that we tend to live among the set of puny integers and generally ignore the vast infinitude of larger ones. How trite and limiting our view! — P.D. Schumer It seems that most children at some age get interested in large numbers. “What comes after a thousand? After a million? After a billion?”, et cetera, are common questions. Obviously there is no limit; whatever number you name, a larger one can be obtained simply by adding one. But what is interesting is just how large a number can be expressed in a fairly compact way. Using the standard arithmetic operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division and exponentia- tion), what is the largest number you can make using three copies of the digit “9”? It’s pretty clear we should just stick to exponents, and given that, here are some possibilities: 999, 999, 9 999, and 99 . 9 9 Already we need to be a little careful with the final one: 99 . Does this mean: (99)9 or 9(9 )? Since (99)9 = 981 this interpretation would gain us very little. If this were the standard definition, then why c not write ab as abc? Because of this, a tower of exponents is always interpreted as being evaluated from d d c c c (c ) right to left. In other words, ab = a(b ), ab = a(b ), et cetera. 9 With this definition of towers of exponents, it is clear that 99 is the best we can do.