Remember the Maine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JCC Rockland Travel with the J

In 1908, the first Sephardic immigrants arrived in Cuba, mostly from Turkey, and to a lesser degree, from Syria and Greece. In 1914, the first Sephardic synagogue was founded. Its name was Shevet Achim Hebrew Union. It functioned until 1995, when it became necessary to close its doors due to its state of disrepair. Successive waves of immigration took place around the First and Second World Wars. At the time this happened, there were in existence in the capital of Cuba two Sephardic synagogues. One of them, founded in 1954, the Sephardic Hebrew Center of Cuba, is still functioning presently. It is the only Sephardic synagogue in Havana City. Presently, approximately 65% of the total Jewish population of the country is Sephardic. We will go to the to Sephardic Hebrew Center and meet with Dr. Myra Levy, president of the congregation followed by fellowship and interaction with members of the community.Lunch on your own. We proceed to Muraleando, to see artists and musicians rebuilding their neighborhood. CUBA Farewell dinner at a Paladar. DAY 9 MARCH 8-16, 2017 THURSDAY, MARCH 16 Breakfast and departure to the airport. Cuba, a Caribbean gem, is a cultural oasis of We’ve been on tours all over the world, but I will have to say that this particular trip was one of the best. Not only did warm, generous people. Be inspired by Cuba’s we learn more about Jewish history, especially in a place like Cuba, because Miriam is Cuban born, there was Miriam’s personal story and point-of-view to everything we saw soulful art, musical rhythms and vibrant dance. -

Race, Nation, and Popular Culture in Cuban New York City and Miami, 1940-1960

Authentic Assertions, Commercial Concessions: Race, Nation, and Popular Culture in Cuban New York City and Miami, 1940-1960 by Christina D. Abreu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American Culture) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof Associate Professor Richard Turits Associate Professor Yeidy Rivero Associate Professor Anthony P. Mora © Christina D. Abreu 2012 For my parents. ii Acknowledgments Not a single word of this dissertation would have made it to paper without the support of an incredible community of teachers, mentors, colleagues, and friends at the University of Michigan. I am forever grateful to my dissertation committee: Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, Richard Turits, Yeidy Rivero, and Anthony Mora. Jesse, your careful and critical reading of my chapters challenged me to think more critically and to write with more precision and clarity. From very early on, you treated me as a peer and have always helped put things – from preliminary exams and research plans to the ups and downs of the job market – in perspective. Your advice and example has made me a better writer and a better historian, and for that I thank you. Richard, your confidence in my work has been a constant source of encouragement. Thank you for helping me to realize that I had something important to say. Yeidy, your willingness to join my dissertation committee before you even arrived on campus says a great deal about your intellectual generosity. ¡Mil Gracias! Anthony, watching you in the classroom and interact with students offered me an opportunity to see a great teacher in action. -

China Behind Raúl's Economic Reforms, Says Expert in Chinese

Vol. 21, No. 7 July 2013 In the News China behind Raúl’s economic reforms, Reforms announced says expert in Chinese-Cuban relations DeregUlation of state firms to begin; GDP BY VITO ECHEVARRÍA another 1,000 bUses in 2008 — replacing the infamoUs hUmp-shaped bUses Univer- growth forecast downgraded .......Page 4 verage CUbans can now sell hoUses and “camello” apartments to each other, bUdding entre- sally hated by habaneros. There was also a 2006 deal in which Chinese ApreneUrs may offer goods and services Political briefs manUfactUrer Haier sUpplied CUba with 300,000 directly to consUmers — withoUt going throUgh new energy-efficient refrigerators, as part of the GOP tries to restrict travel to CUba; revived the state — and the island’s new immigration Castro regime’s plan to finally rid the island of interest in CUba certified claims ...Page 5 law permits foreign real-estate owners and long- antiqUated, mostly American-made fridges. term renters to obtain renewable visas. “These kinds of trade interactions have been AUstralian academic Adrian Hearn says all accompanied by some pretty intensive dialogUe Corruption on trial these people can thank the Chinese for pUshing with China aboUt how the [CUban] economy can Canadian expert Gregory Biniowsky says President Raúl Castro to reform the economy. develop,” Hearn said. Raúl’s anti-corrUption campaign is good for Speaking May 22 at New York’s CUNY “This has been happening since 1995 when GradUate School, Hearn explained how China Fidel Castro visited Beijing and met Prime foreign investors in long rUn .........Page 6 — along with VenezUela — has become a vital Minister Li Pong, who advised him in no Uncer- economic lifeline for CUba. -

Full Itinerary

CUBA November 7-14, 2016 University of Redlands Day 1 Miami Monday, November 7 Travelers arrive in Miami independently on Monday, November 7. Crowne Plaza Hotel is located 5 minutes from MIA Airport. Free shuttle service to and from the Miami airport every 20 minutes. Look for signs indicating where hotel shuttles pick up passengers in the departure level (2nd floor). Taxis are also available. Check in to Crowne Plaza Hotel. A reservation has been made for you. Crowne Plaza Miami International Airport 950 NW Le Jeune Rd. Miami, FL 33126 Tel: (305) 446-9000 7:00 pm Group meets in the lobby of the hotel. Meet-and-greet in nearby conference room. 8:00 pm Dinner Day 2 Tuesday, November 8: Miami to Havana 6:00 am Group meets in the lobby of the Crowne Plaza Hotel to board shuttle for the airport 6:30 am Check-in at Miami International Airport (MIA) for Havana Air flight #EA3141 operated by Eastern Airlines. Havana Air flight departs from Concourse G. There is a Havana Air check- in counter near Dunkin Donuts. (Note: Flight departure time and details will be confirmed at a later date) 9:00 am Depart from Miami to Havana. Flight duration is 1 hour. 10:00 am Arrive in Havana. Clear customs and immigration (approximately 1 hour). 11:30 am Visit the Plaza de la Revolución, the center of government also commonly used for massive rallies. 12:00 pm Lunch at VIP Havana. Itinerary subject to change. 1 VIP Havana ranks among the most stylish paladares in Havana, and its airy interior is strikingly modern (especially compared to its more historically minded brethren). -

An Ethnomusicological Study of the Policies and Aspirations for US

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 Beyond the Blockade: An Ethnomusicological Study of the Policies and Aspirations for U.S.-Cuban Musical Interaction Timothy P. Storhoff Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC BEYOND THE BLOCKADE: AN ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL STUDY OF THE POLICIES AND ASPIRATIONS FOR U.S.-CUBAN MUSICAL INTERACTION By TIMOTHY P. STORHOFF A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2014 Timothy Storhoff defended this dissertation on April 2, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Frank Gunderson Professor Directing Dissertation José Gomáriz University Representative Michael B. Bakan Committee Member Denise Von Glahn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To Mom and Dad, for always encouraging me to write and perform. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was made possible through the support, assistance and encouragement of numerous individuals. I am particularly grateful to my advisor, Frank Gunderson, and my dissertation committee members, Michael Bakan, Denise Von Glahn and José Gomáriz. Along with the rest of the FSU Musicology faculty, they have helped me refine my ideas and ask the right questions while exemplifying the qualities required of outstanding educators and scholars. From the beginning of my coursework through the completion of my dissertation, I could not have asked for a finer community of colleagues, musicians and scholars than the musicologists at the Florida State University. -

Cuba Educational Travel Havana – Cienfuegos – Pinar Del Rio Educational Trip Draft October 22 – October 30. 2013

Cuba Educational Travel Havana – Cienfuegos – Pinar del Rio Educational Trip Draft October 22 – October 30. 2013 Day 1 – October 22, 2013 *** Arrive in Miami and check-in at the Crowne Plaza Hotel the night before Day 2 – October 23, 2013 *** Depart Miami at 10 am, arriving in Cienfuegos at 11 am Proceed to the Hotel Union , Cienfuegos’ finest hotel, located in the city’s center Following check-in we will do a quick overview of agenda , discussion of current events, what you need to know about the trip to get everyone up to speed about our upcoming week in Cuba Lunch at Palacio del Valle restaurant . This stunning palace, completed in 1917 by a sugar merchant, was once a casino and is now the home of a picturesque restaurant with a sea view. Cuba overview briefing by Collin Laverty , Cuba Educational Travel President Walking tour of historic center of Cienfuegos led by the City Historian’s office Afternoon visit to the Maroya Gallery to meet with owner Miguel Ángel Rodríguez and local artists who have organized and promoted their art internationally through this community gallery. Discussion with young artists about their work and their plans and visions for the future Music and cocktails with the local chapter of UNEAC, the National Union of Artists and Writers of Cuba, featuring an interactive discussion with photographers, musicians and other locals, followed by live music and dance Dinner as a group at a local paladar Day 3 – October 24, 2013 Day trip to Trinidad , a UNESCO world heritage site, known for its cobble stoned streets, pastel colored homes and small-town feel City Tour with Nancy Benítez , a local architect, historian and restoration specialist Conversation with artist Yami Martínez at her gallery, La Casa de los Conspiradores. -

And the Author(S) 2019 JC Kent, Aesthetics and the Revolutionary

INDEX A aestheticization, 1, 150, 156, 170, Abbott, Berenice, 20 171, 201 Académie des Beaux-Arts (French aesthetics Academy of Fine Arts), 11 Buena Vista aesthetic, 7, 150, 153, Académie des sciences (French 155, 173, 195. See also Buena Academy of Sciences), 11 Vista Social Club (flm) Academy Awards, 153, 162 geographical aesthetics, 1 advertising “post-Special Period” aesthetic, 3, 6, alcohol, 118, 119 86, 90, 108, 117, 140, 150 brand image, 117, 120–126, 129, “post-Castro Cuba” aesthetic, 203, 204 132, 133, 139. See also iconic pre-revolutionary Cuba, 150, 172, branding 173, 186 “city-of-origin” effect, 121, 132 “Special Period” aesthetic, 3, 7, 84, “country-of-origin” effect, 120– 109, 161, 184, 186, 201 121, 123 Afro-Cuban Havana Club, 6, 117–129, 131– photography, representation in, 24, 134, 136, 139–142, 144. See 25, 29–32, 98, 99, 102–104 also Havana Club AfroCubism (project), 151 Havana in, 5, 7, 31, 124, 134, 142 AfroCubism (recording), 151 travel advertisements, 15, 24, 39, “afterimage” (theory), 7, 150, 156, 125–127, 129, 130 173, 185. See also Bruno, Giuliana advertising discourse, 6, 122, 126–128, Air Supply, 184 130, 133, 134, 141, 142, 144 A Lady without Passport, 71 advertising image, 5–7, 118, 119, 122, Álvarez Bravo, Manuel, 103, 104 125–134, 136–142, 146 Antonioni, Michelangelo © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019 211 J. C. Kent, Aesthetics and the Revolutionary City, Studies of the Americas, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64030-3 212 INDEX Blow-up, 92 production of photobooks, 83, 106 Arechabala, Don José, 119, 120. -

Federal Bure

FEDERAL BURE .,' . REGISTRATION ACT - CUBA > .G NEUTRALITY MATTER 7-/p a$ aka a See Cover Page Ea "( Ep. COPIES MADE: -. 10 - Bureau (105-70973)(RM) 1 U. S. Customs (RM) - - -- 1 - ONI, DIO, 6th ND (RM) Charleston,S.C. 1 - U. S. Border Patrol (RM) Tampa, Fla. d 1 - INS, Miami (RM) 1 - OSI, MacMll AFB, Fla. (RM) 1 - G-2, Ft. kpherson, Ga. (RM) 2 - Cleveland 5 - Miami (105-1563) (1 - 105-2006) - ,- (1 - 105-1742) LEADS (continued) At Miami, Fla. "3 \: c Will await coverage of Cleveland lead; if negative, will write closing report reflecting subject has left the ,?- * 4 country, 10st his U. S. Citizenship and taken Cuban 1 : - Citizenship. ADMINISTRATIVE This report is classified Secret inasmuch as it contains information obtained from CIA communications so classified. Anw extra copy of this report is furnished the Bureau for transmittal to the Legat, Havana.b) B - COVER PAGE - Miami is continuing its inquiry of BARTONE and during the coursed investigation will attempt to develop additional information regarding the activities of subject and his relationship with BARTONE .&) It is noted the period of this report extends from Mag 21, 1959 to March 9, 1960. Pertinent information set forth in his report- has been furnished to the Bureau previously in cormmications under this caption, as well as under caption of other leading revolutionary figures in Miami, including DOMINICK BARTONE .(3) e INFORMANTS I Identity Location of Original In£onnation MU T-2 is 8 0PSI, H~vBP(I,, by LA JAMES T. UVEBIITY I MM-T-3 is teport of ~egat, "W- _ _-___ ._ - grmU &tad 5/30/59 I , . -

Congregation B'nai Havurah April 15

Congregation B’nai Havurah April 15 - April 23, 2018 La Habana, Cienfuegos, Trinidad de Cuba Join your fellow members, family, and friends on this insightful trip of cultural discovery and humanitarian effort. We will have experiences offered to few travelers to this tropical island nation. You will make a difference in the lives of our Cuban brothers and sisters. And you will experience Cuba Cuban culture's vibrancy and vitality is alive. Cuba is old, some of it is destroyed, and it feels as though time has stopped. But it is full of life from the aroma of cooking food, to the warmth of the people, to the rhythm in the way people move, to the sound of music in the air. Cuba is changing Rapidly; Now is the Time! There is Still Time to Experience Cuba the Right Way! Mission package includes: 8 days, 7 nights in Cuba One night in Miami at hotel near Miami airport Prepared by World Passage Ltd. 215 836 0858; [email protected] Meetings with the leadership and members of two synagogues and one provincial Jewish Community Presentation by noted historian on the history of the Jews in Cuba Guided visits to: Hemingway’s home Bellas Artes Museum Museo de la Revolucion Museo Romantico Round trip air from Miami - Havana Cuban Visa and USA Travel License Sixteen included meals Private Choral performance Introduction to Afro Cuban religion through lecture, dance and music Experienced driver; modern A/C bus with W.C. Professional English speaking Cuban guide specialized in Jewish Heritage missions Tips to wait staff at included meals and hotel porters Cuban Medical insurance Guided tour of largest Jewish Cemetery in Cuba Bottled water on the bus Accommodations at (subject to change) MIAMI: Crowne Plaza Hotel – near Miami International airport – One night. -

Cuba Itinerarysheets2.Indd

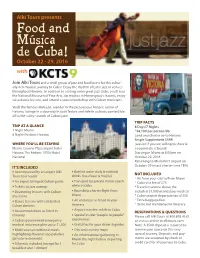

Alki Tours presents Food and Música de Cuba! October 22 - 29, 2016 with Join Alki Tours and a small group of jazz and food lovers for this cultur- ally rich musical journey to Cuba! Enjoy the rhythm of Latin jazz in venues throughout Havana. In addition to visiting some great jazz clubs, you’ll tour the National Museum of Fine Arts, sip mojitos in Hemingway’s haunts, enjoy salsa dance lessons, and attend a special workshop with Cuban musicians. Stroll the famous Malecón, wander in the picturesque historic center of Havana, lounge in a doorway in your fedora and ride in a classic convertible, all to the sultry sounds of Cuban jazz! TRIP FACTS TRIP AT A GLANCE 8 Days/7 Nights 1 Night Miami *$4,199 per person/do 6 Nights historic Havana Land and charter air to Havana Single Supplement $599 WHERE YOU’LL BE STAYING (waived if you are willing to share & Miami: Crowne Plaza airport hotel a roommate is found) Havana: The historic 1930s Hotel Starting in Miami at 8:00pm on Nacional October 22, 2016 Returning to Miami Int’l airport on October 29 (exact charter time TBA) IT’S INCLUDED Accompanied by an expert Alki Bottled water daily & national • • NOT INCLUDED Tours tour leader drinks (local beer & mojito) * Air from your city to/from Miami • An expert bilingual Cuban guide • Transport by private motor coach * Cuba visa fee of $75 • Tickets to jazz outings while in Cuba * Travel insurance above the • Drumming lessons with Cuban • Roundtrip charter flight from included $1,000 mandatory medical musicians Miami * Cuban airport departure tax of $30 • Dance lessons with celebrated • All entrances as listed in your * Extra baggage fees Cuban dancers itinerary * Items not mentioned in itinerary Airport transfers while in Cuba • Accommodations as listed in • RESERVATIONS & QUESTIONS itinerary • Special insider “people to people” Please call Alki Tours at 800.895.ALKI • Cuban government emergency experiences or visit us online at alkitours.com. -

Discover Havana & Imagine Your Next Dance!

Guide La Habana Free www.lahabana.travel Havana in its fi ve centuries The town founded at the south coast near the actual Melena del Sur around 1514, according to the Julian calendar, was baptized as San Cristobal de La Habana and was definitively settled on the north, in the Habaguanex cacique’s domain after many removals. In 1519, the place where El Templete, the small Greco-Roman temple is now, was the stage for the first mass and town council session celebrated under a leafy Ceiba tree. This event marked the foundation of the city that grew and became the economic and government center of the archipelago. Havana is the capital, the head of the nation, but at the same time is the representation of all cultural, intellectual, political, historical and social values of the Cuban people. It is also a catalog of the island’s dazzling architecture that can be observed in the modern neighborhoods of Miramar and Vedado, in a historic center with Moorish constructions influenced by Spaniards and Muslims, with gothic churches like that of Santo Angel and Reina, with the baroque Cathedral of Havana and Museum of Fine Arts, with the neoclassical Templete and the recently restored National Capitol building, and also in the incredibly eclectic Centro Habana neighborhood, full of gargoyles, atlantes, extraordinary figures and imaginary creatures whose most outstanding example is the Gran Teatro de La Habana. This unique mixture also includes the magnificent art nouveau Cueto building at Plaza Vieja, recently restored and turned into a comfortable hotel, and the Bacardi building clear example of art deco in the capital. -

People to People Cultural Exchange

CUBA November 7-14, 2016 University of Redlands $5,800.00 double occupancy $1,700 supplement for single occupancy Please note that the highlighted items are part of the Redlands Signature Experience, which elevate this trip beyond typical Cuban Travel. Day 1 Miami Monday, November 7 Travelers arrive in Miami independently on Monday, November 7. Crowne Plaza Hotel is located 5 minutes from MIA Airport. Free shuttle service to and from the Miami airport every 20 minutes. Look for signs indicating where hotel shuttles pick up passengers in the departure level (2nd floor). Taxis are also available. Check in to Crowne Plaza Hotel. A reservation has been made for you. Crowne Plaza Miami International Airport 950 NW Le Jeune Rd. Miami, FL 33126 Tel: (305) 446-9000 Day 2 Tuesday, November 8: Miami to Havana 9:00 am Group meets in the lobby of the Crowne Plaza Hotel to board shuttle for the airport 9:30 pm Check-in at Miami International Airport (MIA) for ABC Charter flight #AA9476 operated by American Airlines. Check-in is located in Concourse D. (Note: Flight departure time and details will be confirmed at a later date) 12:00 pm Depart from Miami to Havana. Flight duration is 1 hour. 1:00 pm Arrive in Havana. Clear customs and immigration (approximately 1 hour). 2:30 pm Lunch at El Aljibe. El Aljibe offers a pretty open-air setting and live music while you dine. The popular state-owned restaurant celebrates creole fare. 4:00 pm Check in Hotel Parque Central. Itinerary subject to change.