The Belarus Free Theater on the Global Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belarus Free Theatre Opens up Its Digital Archive to Share 24 Theatrical Productions from the Past 15 Years

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Thursday 2 April 2020 BELARUS FREE THEATRE OPENS UP ITS DIGITAL ARCHIVE TO SHARE 24 THEATRICAL PRODUCTIONS FROM THE PAST 15 YEARS WILL ATTENBOROUGH, STEPHEN FRY, ANDREI KHLYVNIUK, DAVID LAN, JULIET STEVENSON & SAM WEST JOIN NEW FAIRY-TALE-INSPIRED CAMPAIGN #LOVEOVERVIRUS 2020 marks the 15th anniversary of Belarus Free Theatre (BFT), the foremost refugee-led theatre company in the UK and the only theatre in Europe banned by its government on political grounds. Ahead of the announcement of the full programme of BFT’s 15th anniversary celebrations, and in response to the coronavirus pandemic, the company will open up its digital archive to make 24 acclaimed stage productions free to watch online, alongside the launch of a new fairy-tale-inspired campaign: #LoveOverVirus 15 YEARS OF THEATRICAL HIGHLIGHTS FREE TO WATCH ONLINE Belarus Free Theatre began 15 years ago this week – on 30 March 2005 – in Minsk under Europe's last surviving dictatorship. Since 2011, the company has been based between Minsk and London where its co-founding Artistic Directors, Natalia Kaliada and Nicolai Khalezin, are political refugees in the UK. New productions are created and rehearsed over Skype before premiering in continually changing underground locations in and around Minsk. Over the past decade, BFT has - through necessity - pioneered creating award-winning theatre at distance and will now share a raft of its theatrical highlights with audiences online at a time when more than a third of the world’s population is adapting to daily life under lockdown. Beginning this Saturday (4 April), and continuing each weekend for the next three months, 24 productions will be made available to watch online on BFT’s YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/c/BelarusFreeTheatre Each production listed below will air on the date indicated at 8pm GMT and will be available to watch for the following 24 hours. -

Is Time Running out for Democracy in Belarus?

Is Time Running Out for Democracy in Belarus? Thursday, 17th December 2020 at 5pm Following a flawed election in August 2020, which was neither free nor fair, Belarusians have protested the denial of democracy. Thousands of protesters have been arrested. Detention is widespread. Hundreds have been subjected to torture and other prohibited ill treatment. Police use of force is routine. Ten protesters have been killed. The authorities act with impunity. The pioneers of democracy in Belarus are either in prison or forced into exile. The acknowledged leader of the democratic Belarus movement, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, continues to call for free and fair elections and to galvanise democracies across the globe in support of democracy in Belarus. Alexander Lukashenko, the last dictator in Europe, reasserts his grip on power. After four months of protests, what options are there for democracy in Belarus? This webinar will bring together the key international actors and we will grapple with the issues facing democratic Belarus. How do we make sanctions meaningful? Will there be accountability for the serious human rights violations taking place in Belarus? Is the potential of the Council of Europe as a broker for peace being overlooked? What can the OSCE achieve? Can Russia’s influence be used to support democracy in Belarus? Can the UN system hold Belarus to account? Will the EU be able to insist that Belarus complies with democratic values? Is there a role for the UK? All these questions and more will be discussed in depth. There will be plenty of opportunities for questions from all those attending. -

The Mediation of the Concept of Civil Society in the Belarusian Press (1991-2010)

THE MEDIATION OF THE CONCEPT OF CIVIL SOCIETY IN THE BELARUSIAN PRESS (1991-2010) A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 IRYNA CLARK School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures ............................................................................................... 5 List of Abbreviations ....................................................................................................... 6 Abstract ............................................................................................................................ 7 Declaration ....................................................................................................................... 8 Copyright Statement ........................................................................................................ 8 A Note on Transliteration and Translation .................................................................... 9 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ 10 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 11 Research objectives and questions ................................................................................... 12 Outline of the Belarusian media landscape and primary sources ...................................... 17 The evolution of the concept of civil society -

Exam Preparation Through Directed Video Blogging Using Electronically-Mediated Realtime Classroom Interaction

2016 ASEE Southeast Section Conference Exam Preparation through Directed Video Blogging and Electronically-Mediated Realtime Classroom Interaction Ronald F. DeMara, Soheil Salehi, and Sindhu Muttineni Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL 32816-2362 e-mail: [email protected] Abstract A structured approach to video blogging (“vlogging”) has been piloted at the University of Central Florida (UCF) as a pedagogical tool to increase engagement in large-enrollment undergraduate courses. This two-phased activity enables a “risk-free” approach of increasing participation from all students enrolled in the course, as well as the opportunity for students who volunteer to advance their technical exposition soft-skills through professional video composition. A review of subject matter content without requiring the viewing of an excessive quantity of vlogs along with a rubric supporting automated grading mechanisms in real-time are some of the objectives that will be met through the implementation of this pedagogical tool. The resulting Learner Video Thumbnailing (LVT) hybrid individual/group exercise offers a highly- engaging interactive means for all students to review course topics in preparation for larger objective formative assessments. Keywords Formative Assessment, Cyberlearning, Student Engagement, vlog, YouTube Introduction Video Blog postings, also known as vlogs in a shared online environment can facilitate learners’ reflective thinking1. In addition, it can provide a medium to express the students’ understanding, triggering a meaning-making process thereby making it a significant aspect of formative assessment in online higher education1, 4, 5, 6, 7. A vlog can be defined as a blog in which the postings are in video format2. -

The State of Artistic Freedom 2021

THE STATE OF ARTISTIC FREEDOM 2021 THE STATE OF ARTISTIC FREEDOM 2021 1 Freemuse (freemuse.org) is an independent international non-governmental organisation advocating for freedom of artistic expression and cultural diversity. Freemuse has United Nations Special Consultative Status to the Economic and Social Council (UN-ECOSOC) and Consultative Status with UNESCO. Freemuse operates within an international human rights and legal framework which upholds the principles of accountability, participation, equality, non-discrimination and cultural diversity. We document violations of artistic freedom and leverage evidence-based advocacy at international, regional and national levels for better protection of all people, including those at risk. We promote safe and enabling environments for artistic creativity and recognise the value that art and culture bring to society. Working with artists, art and cultural organisations, activists and partners in the global south and north, we campaign for and support individual artists with a focus on artists targeted for their gender, race or sexual orientation. We initiate, grow and support locally owned networks of artists and cultural workers so their voices can be heard and their capacity to monitor and defend artistic freedom is strengthened. ©2021 Freemuse. All rights reserved. Design and illustration: KOPA Graphic Design Studio Author: Freemuse Freemuse thanks those who spoke to us for this report, especially the artists who took risks to take part in this research. We also thank everyone who stands up for the human right to artistic freedom. Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of February 2021. -

The EU and Belarus – a Relationship with Reservations Dr

BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION EDITED BY DR. HANS-GEORG WIECK AND STEPHAN MALERIUS VILNIUS 2011 UDK 327(476+4) Be-131 BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION Authors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Dr. Vitali Silitski, Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann, Andrei Yahorau, Dr. Svetlana Matskevich, Valeri Fadeev, Dr. Andrei Kazakevich, Dr. Mikhail Pastukhou, Leonid Kalitenya, Alexander Chubrik Editors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Stephan Malerius This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies and the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication has received funding from the European Parliament. Sole responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication rests with the authors. The Centre for European Studies, the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility either for the information contained in the publication or its subsequent use. ISBN 978-609-95320-1-1 © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin / Berlin © Front cover photo: Jan Brykczynski CONTENTS 5 | Consultancy PROJECT: BELARUS AND THE EU Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck 13 | BELARUS IN AN INTERnational CONTEXT Dr. Vitali Silitski 22 | THE EU and BELARUS – A Relationship WITH RESERvations Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann 34 | CIVIL SOCIETY: AN analysis OF THE situation AND diRECTIONS FOR REFORM Andrei Yahorau 53 | Education IN BELARUS: REFORM AND COOPERation WITH THE EU Dr. Svetlana Matskevich 70 | State bodies, CONSTITUTIONAL REALITY AND FORMS OF RULE Valeri Fadeev 79 | JudiciaRY AND law -

Овчаренко Jewish Theater As a Microdynamic Model

ARTS AND CULTURE AS PARTS OF THE CIVILIZING PROCESSES AT THE TURN OF MILLENNIUM Collective monograph Lviv-Toruń Liha-Pres 2020 Reviewers: Konrad Janowski, PhD, Vice-dean of the Faculty of Psychology, University of Economics and Human Sciences in Warsaw (Republic of Poland); Prof. dr hab. Tadeusz Dmochowski, University of Gdansk (Republic of Poland). Arts and culture as parts of the civilizing processes at the turn of millennium : collective monograph / M. Poplavskyi, T. Humeniuk, Yu. Horban, I. Bondar, A. Furdychko, etc. – Lviv-Toruń : Liha-Pres, 2020. – 152 p. ISBN 978-966-397-197-1 Liha-Pres is an international publishing house which belongs to the category „C” according to the classification of Research School for Socio-Economic and Natural Sciences of the Environment (SENSE) [isn: 3943, 1705, 1704, 1703, 1702, 1701; prefixMetCode: 978966397]. Official website – www.sense.nl. ISBN 978-966-397-197-1 © Liha-Pres, 2020 CONTENTS PIANISM AS A CATEGORY OF PIANO PERFORMANCE Genkin А. А. .................................................................................................. 1 INFORMATION SPACE OF THE MUSIC THESAURUS Kalashnyk M. P. .......................................................................................... 23 SYSTEM SIGNS OF A KAPELLMEISTER’S ACTIVITY Loshkov Yu. I. .............................................................................................. 44 JEWISH THEATER AS A MICRODYNAMIC MODEL NATIONAL CULTURE: THE PARADIGM OF RESEARCH Ovcharenko T. S. ........................................................................................ -

Human Rights for Musicians Freemuse

HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS FREEMUSE – The World Forum on Music and Censorship Freemuse is an international organisation advocating freedom of expression for musicians and composers worldwide. OUR MAIN OBJECTIVES ARE TO: • Document violations • Inform media and the public • Describe the mechanisms of censorship • Support censored musicians and composers • Develop a global support network FREEMUSE Freemuse Tel: +45 33 32 10 27 Nytorv 17, 3rd floor Fax: +45 33 32 10 45 DK-1450 Copenhagen K Denmark [email protected] www.freemuse.org HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS Ten Years with Freemuse Human Rights for Musicians: Ten Years with Freemuse Edited by Krister Malm ISBN 978-87-988163-2-4 Published by Freemuse, Nytorv 17, 1450 Copenhagen, Denmark www.freemuse.org Printed by Handy-Print, Denmark © Freemuse, 2008 Layout by Kristina Funkeson Photos courtesy of Anna Schori (p. 26), Ole Reitov (p. 28 & p. 64), Andy Rice (p. 32), Marie Korpe (p. 40) & Mik Aidt (p. 66). The remaining photos are artist press photos. Proofreading by Julian Isherwood Supervision of production by Marie Korpe All rights reserved CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Human rights for musicians – The Freemuse story Marie Korpe 9 Ten years of Freemuse – A view from the chair Martin Cloonan 13 PART I Impressions & Descriptions Deeyah 21 Marcel Khalife 25 Roger Lucey 27 Ferhat Tunç 29 Farhad Darya 31 Gorki Aguila 33 Mahsa Vahdat 35 Stephan Said 37 Salman Ahmad 41 PART II Interactions & Reactions Introducing Freemuse Krister Malm 45 The organisation that was missing Morten -

Understanding Affective Content of Music Videos Through Learned Representations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten: Publications Understanding Affective Content of Music Videos Through Learned Representations Esra Acar, Frank Hopfgartner, and Sahin Albayrak DAI Laboratory, Technische Universitat¨ Berlin, Ernst-Reuter-Platz 7, TEL 14, 10587 Berlin, Germany {name.surname}@tu-berlin.de Abstract. In consideration of the ever-growing available multimedia data, anno- tating multimedia content automatically with feeling(s) expected to arise in users is a challenging problem. In order to solve this problem, the emerging research field of video affective analysis aims at exploiting human emotions. In this field where no dominant feature representation has emerged yet, choosing discrimi- native features for the effective representation of video segments is a key issue in designing video affective content analysis algorithms. Most existing affective content analysis methods either use low-level audio-visual features or generate hand-crafted higher level representations based on these low-level features. In this work, we propose to use deep learning methods, in particular convolutional neural networks (CNNs), in order to learn mid-level representations from auto- matically extracted low-level features. We exploit the audio and visual modality of videos by employing Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC) and color values in the RGB space in order to build higher level audio and visual represen- tations. We use the learned representations for the affective classification of music video clips. We choose multi-class support vector machines (SVMs) for classi- fying video clips into four affective categories representing the four quadrants of the Valence-Arousal (VA) space. -

The Musicless Music Video As a Spreadable Meme Video: Format, User Interaction, and Meaning on Youtube

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 3634–3654 1932–8036/20170005 The Musicless Music Video as a Spreadable Meme Video: Format, User Interaction, and Meaning on YouTube CANDE SÁNCHEZ-OLMOS1 University of Alicante, Spain EDUARDO VIÑUELA University of Oviedo, Spain The aim of this article is to analyze the musicless music video—that is, a user-generated parodic musicless of the official music video circulated in the context of online participatory culture. We understand musicless videos as spreadable content that resignifies the consumption of the music video genre, whose narrative is normally structured around music patterns. Based on the analysis of the 22 most viewed musicless videos (with more than 1 million views) on YouTube, we aim, first, to identify the formal features of this meme video format and the characteristics of the online channels that host these videos. Second, we study whether the musicless video generates more likes, dislikes, and comments than the official music video. Finally, we examine how the musicless video changes the multimedia relations of the official music video and gives way to new relations among music, image, and text to generate new meanings. Keywords: music video, music meme, YouTube, participatory culture, spreadable media, interaction For the purposes of this research, the musicless video is considered as a user-generated memetic video that alters and parodies an official music video and is spread across social networks. The musicless video modifies the original meaning of the official-version music video, a genre with one of the greatest impacts on the transformation of the audiovisual landscape in the past 10 years. -

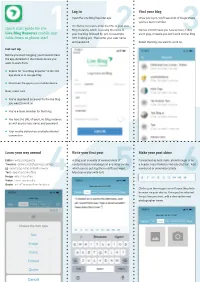

Quick Start Guide for the Live Blog Reporter Mobile

1 Log in 2 Find your blog 3 Open the Live Blog Reporter app. Once you log in, you’ll see a list of blogs where you’re a team member. On the log-in screen, enter the URL of your Live Quick start guide for the Blog instance, which is usually the name of Names in bold mean you have access; if they Live Blog Reporter mobile1 app: your live blog followed by .pro, for example:2 are in grey, it means you can’t work on3 that blog. folds down to phone size! DPA.liveblog.pro. Then enter your user name and password. Select the blog you want to work on. Get set up Before you start blogging, you’ll need to have the app installed on the mobile device you want to work from. Search for “Live Blog Reporter” in the iOS app store or in Google Play Download the app to your mobile device Next, make sure: You’re registered as a user for the live blog you want to work on You’re a team member for that blog You have the URL of your Live Blog instance as well as your user name and password Your mobile device has a reliable internet connection Learn your way around 4 Write your first post 5 Make your post shine 6 Editor - write a blog entry A blog post consists of various kinds of Format text as bold, italic, strikethrough or as Timeline - show a list of previous entries content blocks, including text and other media, a header. -

Does Belarusian-Ukrainian Civilization Belong to the Western Or the Latin Civilization? Piotra Murzionak

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 78 | Number 78 Article 5 4-2018 Does Belarusian-Ukrainian Civilization Belong to the Western or the Latin Civilization? Piotra Murzionak Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Murzionak, Piotra (2018) "Does Belarusian-Ukrainian Civilization Belong to the Western or the Latin Civilization?," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 78 : No. 78 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol78/iss78/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Murzionak: Does Belarusian-Ukrainian Civilization Belong to the Western or t Comparative Civilizations Review 41 Does Belarusian-Ukrainian Civilization Belong to the Western or the Latin Civilization? Piotra Murzionak Abstract The aim of this article is to further develop the idea of the existence of a distinct Belarusian-Ukrainian/Western-Ruthenian civilization, to define its place among Western sub-civilizations, as well as to argue against the designation of Belarus and Ukraine as belonging to the Eurasian civilization. Most of the provided evidence will be related to Belarus; however, it also applies to Ukraine, the country that has had much in common with Belarus in its historical and cultural inheritance since the 9th and 10th centuries. Key words: designation, Belarus, Europe, civilization Introduction The designation of a modern country or group of countries to one or another civilization bears two aspects.