8Organized Crime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

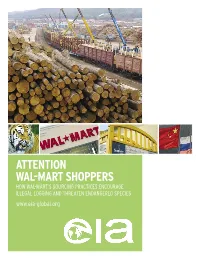

Attention Wal-Mart Shoppers How Wal-Mart’S Sourcing Practices Encourage Illegal Logging and Threaten Endangered Species Contents © Eia

ATTENTION WAL-MART SHOPPERS HOW WAL-MART’S SOURCING PRACTICES ENCOURAGE ILLEGAL LOGGING AND THREATEN ENDANGERED SPECIES www.eia-global.org CONTENTS © EIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Copyright © 2007 Environmental Investigation Agency, Inc. No part of this publication may be 2 INTRODUCTION: WAL-MART IN THE WOODS reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Environmental 4 THE IMPACTS OF ILLEGAL LOGGING Investigation Agency, Inc. Pictures on pages 8,10,11,14,15,16 were published in 6 LOW PRICES, HIGH CONTROL: WAL-MART’S BUSINESS MODEL The Russian Far East, A Reference Guide for Conservation and Development, Josh Newell, 6 REWRITING THE RULES OF THE SUPPLIER-RETAILER RELATIONSHIP 2004, published by Daniel & Daniel, Publishers, Inc. 6 SQUEEZING THE SUPPLY CHAIN McKinleyville, California, 2004. ENVIRONMENTAL INVESTIGATION AGENCY 7 BIG FOOTPRINT, BIG PLANS: WAL-MART’S ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT 7 THE FOOTPRINT OF A GIANT PO Box 53343, Washington DC 20009, USA 7 STEPS FORWARD Tel: +1 202 483 6621 Fax: +1 202 986 8626 Email: [email protected] 8 GLOBAL REACH: WAL-MART’S SALE OF WOOD PRODUCTS Web: www.eia-global.org 8 A SNAPSHOT INTO WAL-MART’S WOOD BUYING AND RETAIL 62-63 Upper Street, London N1 ONY, UK 8 WAL-MART AND CHINESE EXPORTS 8 THE RISE OF CHINA’S WOOD PRODUCTS INDUSTRY Tel: +44(0)20 7354 7960 Fax: +44(0)20 7354 7961 10 CHINA IMPORTS RUSSIA’S GREAT EASTERN FORESTS Email: [email protected] 10 THE WILD WILD FAR EAST 11 CHINA’S GLOBAL SOURCING Web: www.eia-international.org 10 IRREGULARITIES FROM FOREST TO FRONTIER 14 ECOLOGICAL AND SOCIAL IMPACTS 15 THE FLOOD OF LOGS ACROSS THE BORDER 17 LONGJIANG SHANGLIAN: BRIEFCASES OF CASH FOR FORESTS 18 A LANDSCAPE OF WAL-MART SUPPLIERS: INVESTIGATION CASE STUDIES 18 BABY CRIBS 18 DALIAN HUAFENG FURNITURE CO. -

Catalogue of Exporters of Primorsky Krai № ITN/TIN Company Name Address OKVED Code Kind of Activity Country of Export 1 254308

Catalogue of exporters of Primorsky krai № ITN/TIN Company name Address OKVED Code Kind of activity Country of export 690002, Primorsky KRAI, 1 2543082433 KOR GROUP LLC CITY VLADIVOSTOK, PR-T OKVED:51.38 Wholesale of other food products Vietnam OSTRYAKOVA 5G, OF. 94 690001, PRIMORSKY KRAI, 2 2536266550 LLC "SEIKO" VLADIVOSTOK, STR. OKVED:51.7 Other ratailing China TUNGUS, 17, K.1 690003, PRIMORSKY KRAI, VLADIVOSTOK, 3 2531010610 LLC "FORTUNA" OKVED: 46.9 Wholesale trade in specialized stores China STREET UPPERPORTOVA, 38- 101 690003, Primorsky Krai, Vladivostok, Other activities auxiliary related to 4 2540172745 TEK ALVADIS LLC OKVED: 52.29 Panama Verkhneportovaya street, 38, office transportation 301 p-303 p 690088, PRIMORSKY KRAI, Wholesale trade of cars and light 5 2537074970 AVTOTRADING LLC Vladivostok, Zhigura, 46 OKVED: 45.11.1 USA motor vehicles 9KV JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 690091, Primorsky KRAI, Processing and preserving of fish and 6 2504001293 HOLDING COMPANY " Vladivostok, Pologaya Street, 53, OKVED:15.2 China seafood DALMOREPRODUKT " office 308 JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 692760, Primorsky Krai, Non-scheduled air freight 7 2502018358 OKVED:62.20.2 Moldova "AVIALIFT VLADIVOSTOK" CITYARTEM, MKR-N ORBIT, 4 transport 690039, PRIMORSKY KRAI JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 8 2543127290 VLADIVOSTOK, 16A-19 KIROV OKVED:27.42 Aluminum production Japan "ANKUVER" STR. 692760, EDGE OF PRIMORSKY Activities of catering establishments KRAI, for other types of catering JOINT-STOCK COMPANY CITYARTEM, STR. VLADIMIR 9 2502040579 "AEROMAR-ДВ" SAIBEL, 41 OKVED:56.29 China Production of bread and pastry, cakes 690014, Primorsky Krai, and pastries short-term storage JOINT-STOCK COMPANY VLADIVOSTOK, STR. PEOPLE 10 2504001550 "VLADHLEB" AVENUE 29 OKVED:10.71 China JOINT-STOCK COMPANY " MINING- METALLURGICAL 692446, PRIMORSKY KRAI COMPLEX DALNEGORSK AVENUE 50 Mining and processing of lead-zinc 11 2505008358 " DALPOLIMETALL " SUMMER OCTOBER 93 OKVED:07.29.5 ore Republic of Korea 692183, PRIMORSKY KRAI KRAI, KRASNOARMEYSKIY DISTRICT, JOINT-STOCK COMPANY " P. -

The Russia You Never Met

The Russia You Never Met MATT BIVENS AND JONAS BERNSTEIN fter staggering to reelection in summer 1996, President Boris Yeltsin A announced what had long been obvious: that he had a bad heart and needed surgery. Then he disappeared from view, leaving his prime minister, Viktor Cher- nomyrdin, and his chief of staff, Anatoly Chubais, to mind the Kremlin. For the next few months, Russians would tune in the morning news to learn if the presi- dent was still alive. Evenings they would tune in Chubais and Chernomyrdin to hear about a national emergency—no one was paying their taxes. Summer turned to autumn, but as Yeltsin’s by-pass operation approached, strange things began to happen. Chubais and Chernomyrdin suddenly announced the creation of a new body, the Cheka, to help the government collect taxes. In Lenin’s day, the Cheka was the secret police force—the forerunner of the KGB— that, among other things, forcibly wrested food and money from the peasantry and drove some of them into collective farms or concentration camps. Chubais made no apologies, saying that he had chosen such a historically weighted name to communicate the seriousness of the tax emergency.1 Western governments nod- ded their collective heads in solemn agreement. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank both confirmed that Russia was experiencing a tax collec- tion emergency and insisted that serious steps be taken.2 Never mind that the Russian government had been granting enormous tax breaks to the politically connected, including billions to Chernomyrdin’s favorite, Gazprom, the natural gas monopoly,3 and around $1 billion to Chubais’s favorite, Uneximbank,4 never mind the horrendous corruption that had been bleeding the treasury dry for years, or the nihilistic and pointless (and expensive) destruction of Chechnya. -

Russia: CHRONOLOGY DECEMBER 1993 to FEBRUARY 1995

Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/CHRONO... Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets Home Issue Paper RUSSIA CHRONOLOGY DECEMBER 1993 TO FEBRUARY 1995 July 1995 Disclaimer This document was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This document is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate. Table of Contents GLOSSARY Political Organizations and Government Structures Political Leaders 1. INTRODUCTION 2. CHRONOLOGY 1993 1994 1995 3. APPENDICES TABLE 1: SEAT DISTRIBUTION IN THE STATE DUMA TABLE 2: REPUBLICS AND REGIONS OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION MAP 1: RUSSIA 1 of 58 9/17/2013 9:13 AM Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/CHRONO... MAP 2: THE NORTH CAUCASUS NOTES ON SELECTED SOURCES REFERENCES GLOSSARY Political Organizations and Government Structures [This glossary is included for easy reference to organizations which either appear more than once in the text of the chronology or which are known to have been formed in the period covered by the chronology. The list is not exhaustive.] All-Russia Democratic Alternative Party. Established in February 1995 by Grigorii Yavlinsky.( OMRI 15 Feb. -

The Siloviki in Russian Politics

The Siloviki in Russian Politics Andrei Soldatov and Michael Rochlitz Who holds power and makes political decisions in contemporary Russia? A brief survey of available literature in any well-stocked bookshop in the US or Europe will quickly lead one to the answer: Putin and the “siloviki” (see e.g. LeVine 2009; Soldatov and Borogan 2010; Harding 2011; Felshtinsky and Pribylovsky 2012; Lucas 2012, 2014 or Dawisha 2014). Sila in Russian means force, and the siloviki are the members of Russia’s so called “force ministries”—those state agencies that are authorized to use violence to respond to threats to national security. These armed agents are often portrayed—by journalists and scholars alike—as Russia’s true rulers. A conventional wisdom has emerged about their rise to dominance, which goes roughly as follows. After taking office in 2000, Putin reconsolidated the security services and then gradually placed his former associates from the KGB and FSB in key positions across the country (Petrov 2002; Kryshtanovskaya and White 2003, 2009). Over the years, this group managed to disable almost all competing sources of power and control. United by a common identity, a shared worldview, and a deep personal loyalty to Putin, the siloviki constitute a cohesive corporation, which has entrenched itself at the heart of Russian politics. Accountable to no one but the president himself, they are the driving force behind increasingly authoritarian policies at home (Illarionov 2009; Roxburgh 2013; Kasparov 2015), an aggressive foreign policy (Lucas 2014), and high levels of state predation and corruption (Dawisha 2014). While this interpretation contains elements of truth, we argue that it provides only a partial and sometimes misleading and exaggerated picture of the siloviki’s actual role. -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

East Asian Strategic Review 2001 Runoff Election

Chapter 7 Russia ussia entered upon the new century with an energetic young Rleader Vladimir Putin. He seems to be aiming at rebuilding a strong Russia by resolutely facing up to the reality in Russia and by solving problems facing Russia one by one. Nearly ten years under President Boris Yeltsin were a transi- tional period from the old regime of the Communist Party dictator- ship to a new regime based on democracy and market economy. In the sense that he had demolished the old regime, President Yeltsin had made a great success. However, he failed to resolve the confu- sion that had arisen in the course of transition to the new regime and was unable to alleviate the sufferings of the people. What the Russian people expect President Putin to do first is to end the polit- ical and social confusion, and stabilize their livelihood. Putin considers solving domestic problems the top priority of his administration and believes that a strong Russia could not be re- vived without solving these domestic problems. In foreign policy, he stressed that Russia will favor a pragmatic approach for overcom- ing domestic difficulties, and has indicated his willingness to steer clear of troubles that could impair economic relations with the West. In the field of defense and security, he attaches priority to adapting Russia’s military to the country’s needs and economic po- tential. Since he took office President Putin has revised basic documents on diplomacy, national defense and security: Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation, National Security Concept of the Russian Federation and Military Doctrine. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

RUSSIA INTELLIGENCE Politics & Government

N°66 - November 22 2007 Published every two weeks / International Edition CONTENTS KREMLIN P. 1-4 Politics & Government c KREMLIN The highly-orchestrated launching into orbit cThe highly-orchestrated launching into orbit of of the «national leader» the «national leader» Only a few days away from the legislative elections, the political climate in Russia grew particu- STORCHAK AFFAIR larly heavy with the announcement of the arrest of the assistant to the Finance minister Alexey Ku- c Kudrin in the line of fire of drin (read page 2). Sergey Storchak is accused of attempting to divert several dozen million dol- the Patrushev-Sechin clan lars in connection with the settlement of the Algerian debt to Russia. The clan wars in the close DUMA guard of Vladimir Putin which confront the Igor Sechin/Nikolay Patrushev duo against a compet- cUnited Russia, electoral ing «Petersburg» group based around Viktor Cherkesov, overflows the limits of the «power struc- home for Russia’s big ture» where it was contained up until now to affect the entire Russian political power complex. business WAR OF THE SERVICES The electoral campaign itself is unfolding without too much tension, involving men, parties, fac- cThe KGB old guard appeals for calm tions that support President Putin. They are no longer legislative elections but a sort of plebicite campaign, to which the Russian president lends himself without excessive good humour. The objec- PROFILE cValentina Matvienko, the tive is not even to know if the presidential party United Russia will be victorious, but if the final score “czarina” of Saint Petersburg passes the 60% threshhold. -

Power Surge? Russia’S Power Ministries from Yeltsin to Putin and Beyond

Power Surge? Russia’s Power Ministries from Yeltsin to Putin and Beyond PONARS Policy Memo No. 414 Brian D. Taylor Syracuse University December 2006 The “rise of the siloviki ” has become a standard framework for analyzing Russian politics under President Vladimir Putin . According to this view, the main difference between Putin’s rule and that of former president Boris Yeltsin is the triumph of guns (the siloviki ) over money (the oligarchs). This approach has a lot to recommend it, but it also raises sever al important questions . One is the ambiguity embedded in the term siloviki itself . Taken from the Russian phrase for the power ministries ( silovie ministerstva ) or power structures ( silovie strukturi ), the word is sometimes used to refer to those ministrie s and agencies ; sometimes to personnel from those structures ; and sometimes to a specific “clan” in Russian politics centered around the deputy head of the presidential administration, former KGB official Igor Sechin . A second issue , often glossed over in the “rise of the siloviki ” story , is whether the increase in political power of men with guns has necessarily led to the strengthening of the state, Putin’s central policy goal . Finally, as many observers have pointed out, treating the siloviki as a unit – particularly when the term is used to apply to all power ministries or power ministry personnel – seriously overstates the coherence of this group. In this memo, I break down the rise of the siloviki narrative into multiple parts, focusing on three issues . First, I look at change over time, from the early 1990s to the present . -

S:\FULLCO~1\HEARIN~1\Committee Print 2018\Henry\Jan. 9 Report

Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. 1 115TH CONGRESS " ! S. PRT. 2d Session COMMITTEE PRINT 115–21 PUTIN’S ASYMMETRIC ASSAULT ON DEMOCRACY IN RUSSIA AND EUROPE: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY A MINORITY STAFF REPORT PREPARED FOR THE USE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JANUARY 10, 2018 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations Available via World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 28–110 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. 9 REPORT FOREI-42327 with DISTILLER seneagle Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS BOB CORKER, Tennessee, Chairman JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland MARCO RUBIO, Florida ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin JEANNE SHAHEEN, New Hampshire JEFF FLAKE, Arizona CHRISTOPHER A. COONS, Delaware CORY GARDNER, Colorado TOM UDALL, New Mexico TODD YOUNG, Indiana CHRISTOPHER MURPHY, Connecticut JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming TIM KAINE, Virginia JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts ROB PORTMAN, Ohio JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon RAND PAUL, Kentucky CORY A. BOOKER, New Jersey TODD WOMACK, Staff Director JESSICA LEWIS, Democratic Staff Director JOHN DUTTON, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. -

Russia's Looming Crisis

FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE Russia’s Looming Crisis By David Satter Russia’s Looming Crisis By David Satter March 2012 About FPRI - - - Founded in 1955 by Ambassador Robert Strausz Hupé, FPRI is a non partisan,- non profit organization devoted to bringing the insights of scholarship to bear on the development of policies that advance U.S. national interests. In the tradition of Strausz Hupé, FPRI embraces history and geography to illuminate foreign policy challenges facing the United States. In 1990, FPRI established the Wachman Center to foster civic and international literacy in the community and in the classroom. FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE 19102-3684 Tel. 215-732- -732-4401 1528 Walnut Street, Suite 610 • Philadelphia, PA 3774 • Fax 215 Email [email protected] • Website: www.fpri.org Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 1. The Political Situation ........................................................................................................ 3 The Control of the Election Process ............................................................................................ 4 The Economic Key to Putin’s Political Success ....................................................................... 5 A Political Charade ............................................................................................................................ 6 An Election Fraud .............................................................................................................................