Martin Gardner's New Mathematical Diversions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iterations of the Words-To-Numbers Function

1 2 Journal of Integer Sequences, Vol. 21 (2018), 3 Article 18.9.2 47 6 23 11 Iterations of the Words-to-Numbers Function Matthew E. Coppenbarger School of Mathematical Sciences 85 Lomb Memorial Drive Rochester Institute of Technology Rochester, NY 14623-5603 USA [email protected] Abstract The Words-to-Numbers function takes a nonnegative integer and maps it to the number of characters required to spell the number in English. For each k = 0, 1,..., 8, we determine the minimal nonnegative integer n such that the iterates of n converge to the fixed point (through the Words-to-Numbers function) in exactly k iterations. Our travels take us from some simple answers, to an etymology of the names of large numbers, to Conway/Guy’s established system representing the name of any integer, and finally use generating functions to arrive at a very large number. 1 Introduction and initial definitions The idea for the problem originates in a 1965 book [3, p. 243] by recreational linguistics icon Dmitri Borgmann (1927–85) and in a 1966 article [16] by another icon, recreational mathematician Martin Gardner (1914–2010). Gardner’s article appears again in a book [17, pp. 71–72, 265–267] containing reprinted Gardner articles from Scientific American along with his comments on his reader’s responses. Both Borgmann and Gardner identify the only English number that requires exactly the same number of characters to spell the number as the number represents. Borgmann goes further by identifying numbers in 16 other languages with this property. Borgmann calling such numbers truthful and Gardner calling them honest. -

Mathematical Circus & 'Martin Gardner

MARTIN GARDNE MATHEMATICAL ;MATH EMATICAL ASSOCIATION J OF AMERICA MATHEMATICAL CIRCUS & 'MARTIN GARDNER THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Washington, DC 1992 MATHEMATICAL More Puzzles, Games, Paradoxes, and Other Mathematical Entertainments from Scientific American with a Preface by Donald Knuth, A Postscript, from the Author, and a new Bibliography by Mr. Gardner, Thoughts from Readers, and 105 Drawings and Published in the United States of America by The Mathematical Association of America Copyright O 1968,1969,1970,1971,1979,1981,1992by Martin Gardner. All riglhts reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. An MAA Spectrum book This book was updated and revised from the 1981 edition published by Vantage Books, New York. Most of this book originally appeared in slightly different form in Scientific American. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 92-060996 ISBN 0-88385-506-2 Manufactured in the United States of America For Donald E. Knuth, extraordinary mathematician, computer scientist, writer, musician, humorist, recreational math buff, and much more SPECTRUM SERIES Published by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Committee on Publications ANDREW STERRETT, JR.,Chairman Spectrum Editorial Board ROGER HORN, Chairman SABRA ANDERSON BART BRADEN UNDERWOOD DUDLEY HUGH M. EDGAR JEANNE LADUKE LESTER H. LANGE MARY PARKER MPP.a (@ SPECTRUM Also by Martin Gardner from The Mathematical Association of America 1529 Eighteenth Street, N.W. Washington, D. C. 20036 (202) 387- 5200 Riddles of the Sphinx and Other Mathematical Puzzle Tales Mathematical Carnival Mathematical Magic Show Contents Preface xi .. Introduction Xlll 1. Optical Illusions 3 Answers on page 14 2. Matches 16 Answers on page 27 3. -

Single Digits

...................................single digits ...................................single digits In Praise of Small Numbers MARC CHAMBERLAND Princeton University Press Princeton & Oxford Copyright c 2015 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved The second epigraph by Paul McCartney on page 111 is taken from The Beatles and is reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown Group Ltd., London on behalf of The Beneficiaries of the Estate of Hunter Davies. Copyright c Hunter Davies 2009. The epigraph on page 170 is taken from Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince:Copyrightc J.K. Rowling 2005 The epigraphs on page 205 are reprinted wiht the permission of the Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., from Born on a Blue Day: Inside the Extraordinary Mind of an Austistic Savant by Daniel Tammet. Copyright c 2006 by Daniel Tammet. Originally published in Great Britain in 2006 by Hodder & Stoughton. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chamberland, Marc, 1964– Single digits : in praise of small numbers / Marc Chamberland. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-16114-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Mathematical analysis. 2. Sequences (Mathematics) 3. Combinatorial analysis. 4. Mathematics–Miscellanea. I. Title. QA300.C4412 2015 510—dc23 2014047680 British Library -

Neutral Emergence and Coarse Graining Cellular Automata

NEUTRAL EMERGENCE AND COARSE GRAINING CELLULAR AUTOMATA Andrew Weeks Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of York Department of Computer Science March 2010 Neutral Emergence and Coarse Graining Cellular Automata ABSTRACT Emergent systems are often thought of as special, and are often linked to desirable properties like robustness, fault tolerance and adaptability. But, though not well understood, emergence is not a magical, unfathomable property. We introduce neutral emergence as a new way to explore emergent phe- nomena, showing that being good enough, enough of the time may actu- ally yield more robust solutions more quickly. We then use cellular automata as a substrate to investigate emergence, and find they are capable of exhibiting emergent phenomena through coarse graining. Coarse graining shows us that emergence is a relative concept – while some models may be more useful, there is no correct emergent model – and that emergence is lossy, mapping the high level model to a subset of the low level behaviour. We develop a method of quantifying the ‘goodness’ of a coarse graining (and the quality of the emergent model) and use this to find emergent models – and, later, the emergent models we want – automatically. i Neutral Emergence and Coarse Graining Cellular Automata ii Neutral Emergence and Coarse Graining Cellular Automata CONTENTS Abstract i Figures ix Acknowledgements xv Declaration xvii 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Neutral emergence 1 1.2 Evolutionary algorithms, landscapes and dynamics 1 1.3 Investigations with -

Diary Presage Instructions

DIARY PRESAGE INSTRUCTIONS PAUL ROMHANY MIKE MAIONE Copyright © 2013 Paul Romhany, Mike Maione All rights reserved. DEDICATION This routine is dedicated to our wives who put up with us asking them to keep thinking of a day in the week. CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION!-----------------------------------1 2 BASIC WORKINGS!--------------------------------2 3 PROVERB ROUTINE!-----------------------------4 4 SCRATCH & WIN PREDICTION!---------------9 5 COLOR PREDICTION!---------------------------12 6 TRIBUTE TO HOY!-------------------------------14 7 ROYAL FLUSH!------------------------------------15 8 FORTUNE COOKIE!------------------------------16 9 ACAAN WEEK!-------------------------------------20 10 MIND READING WORDS!--------------------23 11. BIRTHDAY CARD TRICK!--------------------29 12. BIRTHDAY CARD TRICK 2!------------------35 13. BOOK TEST!-------------------------------------37 14. DISTRESSING!----------------------------------38 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to acknowledge the following people. Richard Webster, Stanley Collins, Terry Rogers, Long Island’s C.U.E. Club, Joe Silkie 1 INTRODUCTION Thank you for purchasing Diary Presage. We truly believe you have in your procession one of the strongest book tests, certainly the strongest Diary type book test ever devised. A statement we don’t use lightly and after reading these instructions and using the book we think you’ll agree. The concept originally came about after I reviewed another book test by Mike using the same principle called Celebrity Presage. I contacted Mike with my idea for the diary and together we worked on producing Diary Presage. It went through many stages until we got it to what you have now, and in collaboration with Richard Webster and Atlas Brookings we can now offer the fraternity this amazing product. After working this ourselves we both realize the hardest part is holding back and not performing all the routines at once. -

Name of Game Date of Approval Comments Nevada Gaming Commission Approved Gambling Games Effective August 1, 2021

NEVADA GAMING COMMISSION APPROVED GAMBLING GAMES EFFECTIVE AUGUST 1, 2021 NAME OF GAME DATE OF APPROVAL COMMENTS 1 – 2 PAI GOW POKER 11/27/2007 (V OF PAI GOW POKER) 1 BET THREAT TEXAS HOLD'EM 9/25/2014 NEW GAME 1 OFF TIE BACCARAT 10/9/2018 2 – 5 – 7 POKER 4/7/2009 (V OF 3 – 5 – 7 POKER) 2 CARD POKER 11/19/2015 NEW GAME 2 CARD POKER - VERSION 2 2/2/2016 2 FACE BLACKJACK 10/18/2012 NEW GAME 2 FISTED POKER 21 5/1/2009 (V OF BLACKJACK) 2 TIGERS SUPER BONUS TIE BET 4/10/2012 (V OF BACCARAT) 2 WAY WINNER 1/27/2011 NEW GAME 2 WAY WINNER - COMMUNITY BONUS 6/6/2011 21 + 3 CLASSIC 9/27/2000 21 + 3 CLASSIC - VERSION 2 8/1/2014 21 + 3 CLASSIC - VERSION 3 8/5/2014 21 + 3 CLASSIC - VERSION 4 1/15/2019 21 + 3 PROGRESSIVE 1/24/2018 21 + 3 PROGRESSIVE - VERSION 2 11/13/2020 21 + 3 XTREME 1/19/1999 (V OF BLACKJACK) 21 + 3 XTREME - (PAYTABLE C) 2/23/2001 21 + 3 XTREME - (PAYTABLES D, E) 4/14/2004 21 + 3 XTREME - VERSION 3 1/13/2012 21 + 3 XTREME - VERSION 4 2/9/2012 21 + 3 XTREME - VERSION 5 3/6/2012 21 MADNESS 9/19/1996 21 MADNESS SIDE BET 4/1/1998 (V OF 21 MADNESS) 21 MAGIC 9/12/2011 (V OF BLACKJACK) 21 PAYS MORE 7/3/2012 (V OF BLACKJACK) 21 STUD 8/21/1997 NEW GAME 21 SUPERBUCKS 9/20/1994 (V OF 21) 211 POKER 7/3/2008 (V OF POKER) 24-7 BLACKJACK 4/15/2004 2G'$ 12/11/2019 2ND CHANCE BLACKJACK 6/19/2008 NEW GAME 2ND CHANCE BLACKJACK – VERSION 2 9/24/2008 2ND CHANCE BLACKJACK – VERSION 3 4/8/2010 3 CARD 6/24/2021 NEW GAME NAME OF GAME DATE OF APPROVAL COMMENTS 3 CARD BLITZ 8/22/2019 NEW GAME 3 CARD HOLD’EM 11/21/2008 NEW GAME 3 CARD HOLD’EM - VERSION 2 1/9/2009 -

Notices of the American Mathematical

ISSN 0002-9920 Notices of the American Mathematical Society AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Graduate Studies in Mathematics Series The volumes in the GSM series are specifically designed as graduate studies texts, but are also suitable for recommended and/or supplemental course reading. With appeal to both students and professors, these texts make ideal independent study resources. The breadth and depth of the series’ coverage make it an ideal acquisition for all academic libraries that of the American Mathematical Society support mathematics programs. al January 2010 Volume 57, Number 1 Training Manual Optimal Control of Partial on Transport Differential Equations and Fluids Theory, Methods and Applications John C. Neu FROM THE GSM SERIES... Fredi Tro˝ltzsch NEW Graduate Studies Graduate Studies in Mathematics in Mathematics Volume 109 Manifolds and Differential Geometry Volume 112 ocietty American Mathematical Society Jeffrey M. Lee, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, American Mathematical Society TX Volume 107; 2009; 671 pages; Hardcover; ISBN: 978-0-8218- 4815-9; List US$89; AMS members US$71; Order code GSM/107 Differential Algebraic Topology From Stratifolds to Exotic Spheres Mapping Degree Theory Matthias Kreck, Hausdorff Research Institute for Enrique Outerelo and Jesús M. Ruiz, Mathematics, Bonn, Germany Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain Volume 110; 2010; approximately 215 pages; Hardcover; A co-publication of the AMS and Real Sociedad Matemática ISBN: 978-0-8218-4898-2; List US$55; AMS members US$44; Española (RSME). Order code GSM/110 Volume 108; 2009; 244 pages; Hardcover; ISBN: 978-0-8218- 4915-6; List US$62; AMS members US$50; Ricci Flow and the Sphere Theorem The Art of Order code GSM/108 Simon Brendle, Stanford University, CA Mathematics Volume 111; 2010; 176 pages; Hardcover; ISBN: 978-0-8218- page 8 Training Manual on Transport 4938-5; List US$47; AMS members US$38; and Fluids Order code GSM/111 John C. -

Identifying, Measuring, and Defining Equitable Mathematics Instruction

Identifying, Measuring, and Defining Equitable Mathematics Instruction by Imani Dominique Goffney A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Education) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor Deborah Loewenberg Ball, Chair Professor Hyman Bass Professor Percy Bates Associate Professor Robert B. Bain Assistant Professor Vilma Mesa © Imani Masters Goffney 2010 DEDICATION My princesses Bria and Naima Remember that with faith, hard work, and God you can do anything! ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been written without the tremendous support, guidance, encouragement, and friendship I received from my family, ―family‖, friends, and colleagues. I would first like to thank my family. To Brian for being everything I needed (co- parent, spades partner, dishwasher, editor, supportive shoulder) to help me get through this process. This process tested the boundaries of his patience, but he stepped up, learning to do bath, homework, cook, comb hair, and edit chapters. Thanks for being willing to both wipe away my tears and tell me when it was time to get over it. We celebrate this milestone together. Thanks to my beautiful and wonderful daughters, Bria and Naima, who have brought me more joy than I can say. Thanks Bria for being such an awesome daughter and for all of your patience and support. I know this was hard on you at times, and you handled my being busy with grace and love and I really appreciate it. To my little Naima who always makes me smile and is a perfect example of joy, love, patience, and friendship. -

Horological 10

Ladies' Mesh Watch Bands to Fit Seiko, Pulsar, Citizen And Many Other Brands! LADIES1 MESH WATCHBANDS Now you can offer your customers a quality micron plated or stainless band SLIDING CLASPS at a reasonable price and keep the extra profit for yourself I Width at case Sliding clasps complete with top is 9.8mm, width of fork end is 8mm, & portions. Fits Lorus, Sharp and width at clasp is 7mm. many others! Available in 6, 7, 8 & Need 15mm. Yellow & White. it tomorrow? $8.95Y $4.95 S/S $3.50 each Call us today! POPULAR FOLDOVER ... · CLASPS Our popular clasps fit Seiko, CENTER CATCHES ;: ,,, Pulsar and many others. These handy catches fit many brands Available separately or in an assort - and at this low price, you'll want to ment! Available Sizes: stock up! Available Widths: 2, 3, 4, 5 . ~: 5,6,7,8,10,15&16mm. & 6mm. Yellow & White. (Assortments Yellow & White. available) $2.95 each Clasp Asst: Contains 1O ea. ladies' & 1O mens' buckle spring bars; 12 ea. Y & W safety $29.95 chains; 12 foldover clasps (1 each A $50.00 5, 6, 7, 8,10, & 15mm in Y & W); SEIKO TYPE SAFETY and a plastic compartment box. Value!! CHAINS First quality with hooks and eyes in gold or rhodium finish. $5.95 I dozen $40per100 ,, ..... National WATS: 800-328-0205 ~~ Esslinger & Co. In Minnesota: 800-392-0334 ~ 1165 Medallion Dr., St. Paul, MN 55120 FAX: (612) 452-4298 ~ ~ P.O. Box 64561, St. Paul, Minnesota 55164 Toll-Free FAX: 800-548-9304 VOLUME 16, NUMBER 8 AUGUST 1992 Found: TM George's Watch! HOROLOGICAL 10 Official Publication of the American Watchmakers-Clockmakers Institute 1992AWI Wes Door 2 PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE Annual Meetings Henry B. -

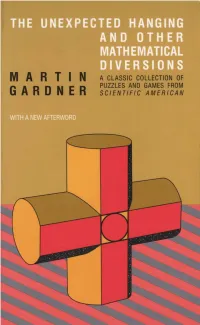

The Unexpected Hanging and Other Mathematical Diversions

AND OTHER MATHEMATICAL nIVERSIONS OLLECTION OF GI ES FRON A ERIC" The Unexpected Hanging A Partial List of Books by Martin Gardner: The Annotated "Casey at the Bat" (ed.) The Annotated Innocence of Father Brown (ed.) Hexaflexagons and Other Mathematical Diversions Logic Machines and Diagrams The Magic Numbers of Dr. Matrix Martin Gardner's Whys and Wherefores New Ambidextrous Universe The No-sided Professor Order and Surprise Puzzles from Other Worlds The Sacred Beetle and Other Essays in Science (ed.) The Second Scientific American Book of Mathematical Puzzles and Diversions Wheels, Life, and Other Mathematical Entertainments The Whys of a Philosopher Scrivener MARTIN GARDNER The Unexpected Hanging And Other Mathematical Diversions With a new Afterword and expanded Bibliography The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London Material previously published in Scientific American is copyright 0 1961, 1962, 1963 by Scientific American, Inc. All rights reserved. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London O 1969, 1991 by Martin Gardner All rights reserved. Originally published 1969. University of Chicago Press edition 1991 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gardner, Martin, 1914- The unexpected hanging and other mathematical diversions : with a new afterword and expanded bibliography 1 Martin Gardner. - University of Chicago Press ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-226-28256-2 (pbk.) 1. Mathematical recreations. I. Title. QA95.G33 1991 793.7'4-dc20 91-17723 CIP @ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 239.48-1984. -

Hollins Student Life (1928 Dec 1) Hollins College

Hollins University Hollins Digital Commons Hollins Student Newspapers Hollins Student Newspapers 12-1-1928 Hollins Student Life (1928 Dec 1) Hollins College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/newspapers Part of the Higher Education Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Social History Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Hollins College, "Hollins Student Life (1928 Dec 1)" (1928). Hollins Student Newspapers. 3. https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/newspapers/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Hollins Student Newspapers at Hollins Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hollins Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Hollins Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. I VOLUME I HOLLINS COLLEGE, DECEMBER I, 1928, HOLLINS, VIRGINIA N UMBE R 5 Evens Defeat Odds In Thanks- ,Odd-Even Hockey . · '. Teams Are Banqueted giving Game By Score ()f. 4 to I Thanksgiving Day was brought to an ap propriate close with an athletic banquet given The Evens .crashed through with another.· well as Fullback, and Harriet Bates made in honor of the two hockey teams. victory this ' year by' defeating ,the Odds by sensational stops and lunges. The shifting of The . banquet tables were arranged in the the score of 4-1. Although this gave them a Patch to Center, Hardy to Wing and Speiden form of a large " H", around which sat forty one persons, all members of the Odd or Even . margin of three points, at · the end of the half to Center Half was another of the big surprises. -

Math Olympics 2000/2002: Intermediate Mathematics Fun for Communities of Children and Adults

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 468 026 SE 065 051 AUTHOR Kundert, Bette L. TITLE Math Olympics 2000/2002: Intermediate Mathematics Fun for Communities of Children and Adults. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 172p.; For the primary level guide, see SE 065 052. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Elementary Education; Evening Programs; *Family Programs; Geometry; *Mathematics Activities; *Mathematics Instruction; Measurement; Number Concepts; *Parent Participation; Probability; *Problem Solving ABSTRACT The materials and ideas in this document are intended to be used by teachers in schools in order to bring adults and children together to experience good mathematics. It features an evening of hands-on mathematics scheduled for one night a week for four weeks. Students and adults come together to share mathematics activities, solve problems, and have fun with mathematics. The activities are intended for intermediate level students. Sessions include measurement and geometry, number concepts and problem solving, estimation and calculators, and data collections and probability. Descriptions of each session and a list of materials are presented. The description of each session includes directions for preparations to be done prior to the event, guidelines on how to present each activity, and solutions to some of the explorations. Hard copies of all worksheets, overhead transparency masters, and graphics mats are included. (ASK) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. MATH U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS CENTER (ERIC) BEEN GRANTED BY This document has been reproducedas OLYMPICS 'ved from the person or organization originating it.