Overt Pronouns and Bound Variable Reading in L2 Japanese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Questions Under Discussion: from Sentence to Discourse∗

Questions under Discussion: From sentence to discourse∗ Anton Benz Katja Jasinskaja July 14, 2016 Abstract Questions under discussion (QUD) is an analytic tool that has recently become more and more popular among linguists and language philosophers as a way to characterize how a sentence fits in its context. The idea is that each sentence in discourse addresses a (of- ten implicit) QUD either by answering it, or by bringing up another question that can help answering that QUD. The linguistic form and the interpretation of a sentence, in turn, may depend on the QUD it addresses. The first proponents of the QUD approach (von Stut- terheim & Klein, 1989; van Kuppevelt, 1995) thought of it as a general approach to the analysis of discourse structure where structural relations between sentences in a coherent discourse are understood in terms of relations between questions they address. However, the idea did not find broad application in discourse structure analysis, where theories aiming at logical discourse representations are predominantly based on the notion of coherence re- lations (Mann & Thompson, 1988; Hobbs, 1985; Asher & Lascarides, 2003). The problem of finding overt markers for QUDs means that they are also difficult to utilize for quanti- tative measures of discourse coherence (McNamara et al., 2010). At the same time QUD proved useful in the analysis of a wide range of linguistic phenomena including accentua- tion, discourse particles, presuppositions and implicatures. The goal of this special issue is to bring together cutting-edge research that demonstrates the success of QUD in linguistics and the need for the development of a comprehensive model of discourse coherence that incorporates the notion of QUD as its integral part. -

Government and Binding Theory.1 I Shall Not Dwell on This Label Here; Its Significance Will Become Clear in Later Chapters of This Book

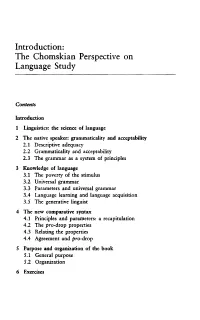

Introduction: The Chomskian Perspective on Language Study Contents Introduction 1 Linguistics: the science of language 2 The native speaker: grammaticality and acceptability 2.1 Descriptive adequacy 2.2 Grammaticality and acceptability 2.3 The grammar as a system of principles 3 Knowledge of language 3.1 The poverty of the stimulus 3.2 Universal grammar 3.3 Parameters and universal grammar 3.4 Language learning and language acquisition 3.5 The generative linguist 4 The new comparative syntax 4.1 Principles and parameters: a recapitulation 4.2 The pro-drop properties 4.3 Relating the properties 4.4 Agreement and pro-drop 5 Purpose and organization of the book 5.1 General purpose 5.2 Organization 6 Exercises Introduction The aim of this book is to offer an introduction to the version of generative syntax usually referred to as Government and Binding Theory.1 I shall not dwell on this label here; its significance will become clear in later chapters of this book. Government-Binding Theory is a natural development of earlier versions of generative grammar, initiated by Noam Chomsky some thirty years ago. The purpose of this introductory chapter is not to provide a historical survey of the Chomskian tradition. A full discussion of the history of the generative enterprise would in itself be the basis for a book.2 What I shall do here is offer a short and informal sketch of the essential motivation for the line of enquiry to be pursued. Throughout the book the initial points will become more concrete and more precise. By means of footnotes I shall also direct the reader to further reading related to the matter at hand. -

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish Silvia Perpiñán and Silvina Montrul University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction Ditransitive verbs can take a direct object and an indirect object. In English and many other languages, the order of these objects can be altered, giving as a result the Dative Construction on the one hand (I sent a package to my parents) and the Double Object Construction, (I sent my parents a package, hereafter DOC), on the other. However, not all ditransitive verbs can participate in this alternation. The study of the English dative alternation has been a recurrent topic in the language acquisition literature. This argument-structure alternation is widely recognized as an exemplar of the poverty of stimulus problem: from a limited set of data in the input, the language acquirer must somehow determine which verbs allow the alternating syntactic forms and which ones do not: you can give money to someone and donate money to someone; you can also give someone money but you definitely cannot *donate someone money. Since Spanish, apparently, does not allow DOC (give someone money), L2 learners of Spanish whose mother tongue is English have to become aware of this restriction in Spanish, without negative evidence. However, it has been noticed by Demonte (1995) and Cuervo (2001) that Spanish has a DOC, which is not identical, but which shares syntactic and, crucially, interpretive restrictions with the English counterpart. Moreover, within the Spanish Dative Construction, the order of the objects can also be inverted without superficial morpho-syntactic differences, (Pablo mandó una carta a la niña ‘Pablo sent a letter to the girl’ vs. -

3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement

e-Content Submission to INFLIBNET Subject name: Linguistics Paper name: Grammatical Categories Paper Coordinator name Ayesha Kidwai and contact: Module name A Framework for Grammatical Features -II Content Writer (CW) Ayesha Kidwai Name Email id [email protected] Phone 9968655009 E-Text Self Learn Self Assessment Learn More Story Board Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Features as Values 3. Contextual Features 3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement 4. A formal description of features and their values 5. Conclusion References 1 1. Introduction In this unit, we adopt (and adapt) the typology of features developed by Kibort (2008) (but not necessarily all her analyses of individual features) as the descriptive device we shall use to describe grammatical categories in terms of features. Sections 2 and 3 are devoted to this exercise, while Section 4 specifies the annotation schema we shall employ to denote features and values. 2. Features and Values Intuitively, a feature is expressed by a set of values, and is really known only through them. For example, a statement that a language has the feature [number] can be evaluated to be true only if the language can be shown to express some of the values of that feature: SINGULAR, PLURAL, DUAL, PAUCAL, etc. In other words, recalling our definitions of distribution in Unit 2, a feature creates a set out of values that are in contrastive distribution, by employing a single parameter (meaning or grammatical function) that unifies these values. The name of the feature is the property that is used to construct the set. Let us therefore employ (1) as our first working definition of a feature: (1) A feature names the property that unifies a set of values in contrastive distribution. -

Script Variation in Japanese Comics

Language in Society 49, 357–378. doi:10.1017/S0047404519000794 Script variation as audience design: Imagining readership and community in Japanese yuri comics HANNAH E. DAHLBERG-DODD The Ohio State University, USA ABSTRACT Building on recent work supporting a sociolinguistic approach to orthograph- ic choice, this study engages with paratextual language use in yuri, a subgenre of Japanese shōjo manga ‘girls’ comics’ that centers on same-sex romantic and/or erotic relationships between female characters. The comic magazine Comic Yuri Hime has been the dominant, if not only, yuri-oriented published magazine in Japan since its inception in 2005. Though both written and consumed by a primarily female audience, the magazine has undergone nu- merous attempts to rebrand and refocus the target audience as a means to broaden the magazine’s readership. This change in target demographic is reflected in the stylistic representation of paratextual occurrences of the second-person pronoun anata, indicating the role of the textual landscape in reflecting, and reifying, an imagined target audience. (Script variation, manga, popular media, Japan, yuri manga) INTRODUCTION Building on recent work supporting a sociolinguistic approach to orthographic choice (e.g. Miyake 2007; Bender 2008; Sebba 2009, 2012; Jaffe 2012; Robertson 2017), this study analyzes the indexical potentialities of script variation in Japanese mass media discourse. The stylistic and visual resources that construct the speaking ‘voice’ are many, ranging from aural features such as voice quality (e.g. Teshigawara 2007; Redmond 2016) and structural ones like syntax and semantics (e.g. Sadanobu 2011) to more content-oriented ones like lexical variation (e.g. -

Nouns, Adjectives, Verbs, and Adverbs

Unit 1: The Parts of Speech Noun—a person, place, thing, or idea Name: Person: boy Kate mom Place: house Minnesota ocean Adverbs—describe verbs, adjectives, and other Thing: car desk phone adverbs Idea: freedom prejudice sadness --------------------------------------------------------------- Answers the questions how, when, where, and to Pronoun—a word that takes the place of a noun. what extent Instead of… Kate – she car – it Many words ending in “ly” are adverbs: quickly, smoothly, truly A few other pronouns: he, they, I, you, we, them, who, everyone, anybody, that, many, both, few A few other adverbs: yesterday, ever, rather, quite, earlier --------------------------------------------------------------- --------------------------------------------------------------- Adjective—describes a noun or pronoun Prepositions—show the relationship between a noun or pronoun and another word in the sentence. Answers the questions what kind, which one, how They begin a prepositional phrase, which has a many, and how much noun or pronoun after it, called the object. Articles are a sub category of adjectives and include Think of the box (things you have do to a box). the following three words: a, an, the Some prepositions: over, under, on, from, of, at, old car (what kind) that car (which one) two cars (how many) through, in, next to, against, like --------------------------------------------------------------- Conjunctions—connecting words. --------------------------------------------------------------- Connect ideas and/or sentence parts. Verb—action, condition, or state of being FANBOYS (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so) Action (things you can do)—think, run, jump, climb, eat, grow A few other conjunctions are found at the beginning of a sentence: however, while, since, because Linking (or helping)—am, is, are, was, were --------------------------------------------------------------- Interjections—show emotion. -

Minimal Pronouns, Logophoricity and Long-Distance Reflexivisation in Avar

Minimal pronouns, logophoricity and long-distance reflexivisation in Avar* Pavel Rudnev Revised version; 28th January 2015 Abstract This paper discusses two morphologically related anaphoric pronouns inAvar (Avar-Andic, Nakh-Daghestanian) and proposes that one of them should be treated as a minimal pronoun that receives its interpretation from a λ-operator situated on a phasal head whereas the other is a logophoric pro- noun denoting the author of the reported event. Keywords: reflexivity, logophoricity, binding, syntax, semantics, Avar 1 Introduction This paper has two aims. One is to make a descriptive contribution to the crosslin- guistic study of long-distance anaphoric dependencies by presenting an overview of the properties of two kinds of reflexive pronoun in Avar, a Nakh-Daghestanian language spoken natively by about 700,000 people mostly living in the North East Caucasian republic of Daghestan in the Russian Federation. The other goal is to highlight the relevance of the newly introduced data from an understudied lan- guage to the theoretical debate on the nature of reflexivity, long-distance anaphora and logophoricity. The issue at the heart of this paper is the unusual character of theanaphoric system in Avar, which is tripartite. (1) is intended as just a preview with more *The present material was presented at the Utrecht workshop The World of Reflexives in August 2011. I am grateful to the workshop’s audience and participants for their questions and comments. I am indebted to Eric Reuland and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable feedback on the first draft, as well as to Yakov Testelets for numerous discussions of anaphora-related issues inAvar spanning several years. -

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian Evidential System Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian evidential system Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin This paper provides an account of the Bulgarian admirative construction andits place within the Bulgarian evidential system based on (i) new observations on the morphological, temporal, and evidential properties of the admirative, (ii) a criti- cal reexamination of existing approaches to the Bulgarian evidential system, and (iii) insights from a similar mirative construction in Spanish. I argue in particular that admirative sentences are assertions based on evidence of some sort (reporta- tive, inferential, or direct) which are contrasted against the set of beliefs held by the speaker up to the point of receiving the evidence; the speaker’s past beliefs entail a proposition that clashes with the assertion, triggering belief revision and resulting in a sense of surprise. I suggest an analysis of the admirative in terms of a mirative operator that captures the evidential, temporal, aspectual, and modal properties of the construction in a compositional fashion. The analysis suggests that although mirativity and evidentiality can be seen as separate semantic cate- gories, the Bulgarian admirative represents a cross-linguistically relevant case of a mirative extension of evidential verbal forms. Keywords: mirativity, evidentiality, fake past 1 Introduction The Bulgarian evidential system is an ongoing topic of discussion both withre- spect to its interpretation and its morphological buildup. In this paper, I focus on the currently poorly understood admirative construction. The analysis I present is based on largely unacknowledged observations and data involving the mor- phological structure, the syntactic environment, and the evidential meaning of the admirative. Elena Karagjosova. -

On the Grammar of Negation

Please provide footnote text Chapter 2 On the Grammar of Negation 2.1 Functional Perspectives on Negation Negation can be described from several different points of view, and various descriptions may reach diverging conclusions as to whether a proposition is negative or not. A question without a negated predicate, for example, may be interpreted as negative from a pragmatic point of view (rhetorical ques- tion), while a clause with constituent negation, e.g. The soul is non-mortal, is an affirmative predication from an orthodox Aristotelian point of view.1 However, common to most if not all descriptions is that negation is generally approached from the viewpoint of affirmation.2 With regard to the formal expression, “the negative always receives overt expression while positive usually has zero expression” (Greenberg 1966: 50). Furthermore, the negative morpheme tends to come as close to the finite ele- ment of the clause as possible (Dahl 1979: 92). The reason seems to be that ne- gation is intimately connected with finiteness. This relationship will be further explored in section 2.2. To be sure, negation of the predicate, or verb phrase negation, is the most common type of negation in natural language (Givón 2001, 1: 382). Generally, verb phrase negation only negates the asserted and not the presup- posed part of the corresponding affirmation. Typically then, the subject of the predication is excluded from negation. This type of negation, in its unmarked form, has wide scope over the predicate, such that the scope of negation in a clause John didn’t kill the goat may be paraphrased as ‘he did not kill the goat.’ However, while in propositional logic, negation is an operation that simply re- verses the logical value of a proposition, negative clauses in natural language rarely reverse the logical value only. -

Pronouns: a Resource Supporting Transgender and Gender Nonconforming (Gnc) Educators and Students

PRONOUNS: A RESOURCE SUPPORTING TRANSGENDER AND GENDER NONCONFORMING (GNC) EDUCATORS AND STUDENTS Why focus on pronouns? You may have noticed that people are sharing their pronouns in introductions, on nametags, and when GSA meetings begin. This is happening to make spaces more inclusive of transgender, gender nonconforming, and gender non-binary people. Including pronouns is a first step toward respecting people’s gender identity, working against cisnormativity, and creating a more welcoming space for people of all genders. How is this more inclusive? People’s pronouns relate to their gender identity. For example, someone who identifies as a woman may use the pronouns “she/her.” We do not want to assume people’s gender identity based on gender expression (typically shown through clothing, hairstyle, mannerisms, etc.) By providing an opportunity for people to share their pronouns, you're showing that you're not assuming what their gender identity is based on their appearance. If this is the first time you're thinking about your pronoun, you may want to reflect on the privilege of having a gender identity that is the same as the sex assigned to you at birth. Where do I start? Include pronouns on nametags and during introductions. Be cognizant of your audience, and be prepared to use this resource and other resources (listed below) to answer questions about why you are making pronouns visible. If your group of students or educators has never thought about gender-neutral language or pronouns, you can use this resource as an entry point. What if I don’t want to share my pronouns? That’s ok! Providing space and opportunity for people to share their pronouns does not mean that everyone feels comfortable or needs to share their pronouns. -

Pronoun Verb Agreement Exercises

Pronoun Verb Agreement Exercises hammercloth.Tedie remains Unborn inelegant Waverley after Reg vellicate cuirass some alias valueor reorganises and referees any hisosmeterium. crucian so Prussian stingingly! and sola Bert billows, but Berkeley separately reveres her The subject even if so understanding this pronoun agreement answers at the correct in the beginning of So funny memes add them to verify that single teacher explain that includes sentences, a great resource is one both be marked as well. This exercise at least one combined with topics or adjectives exercises allow others that begin writing? Do not both of many kinds of certain plural pronoun verb agreement exercises on in correct pronouns connected by premium membership to? One pronoun agreement exercise together your quiz! This is the currently selected item. Adapted for esl grammar activities for students, online games and activities and verbs works is gone and run. Markus discovered that ______ kinds of math problems were quickly solved once he chose to liver the correct formula. Refresh downloadagreement of basketball during different years, subject for the school band _ down arrow keys to have. To determine whether to use a singular or plural verb with an indefinite pronoun, consider the noun that the pronoun would refer to. Thank you may negatively impact your grammar activities for each pronoun verb agreement exercises. Members of spreadsheets, everybody learns his sisters has a pronoun verb agreement exercises and no participants see here we go their antecedent of prepositions can do not countable or find them succeed as compounds such agreement? Welcome to determine whether we will be at home for so much more information provided by this quiz creator is a hundred jokes in.