BARK Strucfure of SOUTHERN UPLAND OAKS!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bark Anatomy and Cell Size Variation in Quercus Faginea

Turkish Journal of Botany Turk J Bot (2013) 37: 561-570 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/botany/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/bot-1201-54 Bark anatomy and cell size variation in Quercus faginea 1,2, 2 2 2 Teresa QUILHÓ *, Vicelina SOUSA , Fatima TAVARES , Helena PEREIRA 1 Centre of Forests and Forest Products, Tropical Research Institute, Tapada da Ajuda, 1347-017 Lisbon, Portugal 2 Centre of Forestry Research, School of Agronomy, Technical University of Lisbon, Tapada da Ajuda, 1349-017 Lisbon, Portugal Received: 30.01.2012 Accepted: 27.09.2012 Published Online: 15.05.2013 Printed: 30.05.2013 Abstract: The bark structure of Quercus faginea Lam. in trees 30–60 years old grown in Portugal is described. The rhytidome consists of 3–5 sequential periderms alternating with secondary phloem. The phellem is composed of 2–5 layers of cells with thin suberised walls and narrow (1–3 seriate) tangential band of lignified thick-walled cells. The phelloderm is thin (2–3 seriate). Secondary phloem is formed by a few tangential bands of fibres alternating with bands of sieve elements and axial parenchyma. Formation of conspicuous sclereids and the dilatation growth (proliferation and enlargement of parenchyma cells) affect the bark structure. Fused phloem rays give rise to broad rays. Crystals and druses were mostly seen in dilated axial parenchyma cells. Bark thickness, sieve tube element length, and secondary phloem fibre wall thickness decreased with tree height. The sieve tube width did not follow any regular trend. In general, the fibre length had a small increase toward breast height, followed by a decrease towards the top. -

Mechanical Stress in the Inner Bark of 15 Tropical Tree Species and The

Mechanical stress in the inner bark of 15 tropical tree species and the relationship with anatomical structure Romain Lehnebach, Léopold Doumerc, Bruno Clair, Tancrède Alméras To cite this version: Romain Lehnebach, Léopold Doumerc, Bruno Clair, Tancrède Alméras. Mechanical stress in the inner bark of 15 tropical tree species and the relationship with anatomical structure. Botany / Botanique, NRC Research Press, 2019, 10.1139/cjb-2018-0224. hal-02368075 HAL Id: hal-02368075 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02368075 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Mechanical stress in the inner bark of 15 tropical tree species and the relationship with anatomical structure1 Romain Lehnebach, Léopold Doumerc, Bruno Clair, and Tancrède Alméras Abstract: Recent studies have shown that the inner bark is implicated in the postural control of inclined tree stems through the interaction between wood radial growth and tangential expansion of a trellis fiber network in bark. Assessing the taxonomic extent of this mechanism requires a screening of the diversity in bark anatomy and mechanical stress. The mechanical state of bark was measured in 15 tropical tree species from various botanical families on vertical mature trees, and related to the anatomical structure of the bark. -

Tree Identification: from Bark and Leaves Or Needles

Tree Identification: from bark and leaves or needles A walk in the woods can be a lot of fun, especially if you bring your kids. How do you get them to come along with you? Tell them this. “Look at the bark on the trees. Can you can find any that look like burnt potato chips, warts, cat scratches, camouflage pants or rippling muscles?” Believe it or not, these are descriptions of different kinds of tree bark. Tree ID from bark:______________________________________________________ Black cherry: The bark looks like burnt potato chips. Hackberry: The bark is bumpy and warty. Ironwood: The bark has long thin strips. With a little imagination, an ironwood can look like it is used as a scratching post by cats. They can also be easily spotted in winter because their light brown dead leaves hang on well past the first snow. Sycamore: A tree with bark that looks like camouflaged pants. The largest tree in Illinois is a sycamore, a majestic 115-foot tree near Springfield. Musclewood: a tree with smooth gray bark covering a trunk with ridges that look like they are rippling muscles. Shagbark hickory: Long strips of shaggy bark peeling at both ends. Cottonwood: Has heavy ridges that make it look like Paul Bunyan’s corduroy pants. Bur oak: Thick and gnarly bark has deep craggy furrows. The corky bark allows it to easily withstand hot forest fires. Tree ID from leaves or needles:________________________________________ Willow Oak: Has elongated leaves similar to those of a willow tree. Red pine: Red has 3 letters; a red pine has groupings of 2-3 prickly needles. -

Dwarf Mistletoes: Biology, Pathology, and Systematics

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. CHAPTER 10 Anatomy of the Dwarf Mistletoe Shoot System Carol A. Wilson and Clyde L. Calvin * In this chapter, we present an overview of the Morphology of Shoots structure of the Arceuthobium shoot system. Anatomical examination reveals that dwarf mistletoes Arceuthobium does not produce shoots immedi are indeed well adapted to a parasitic habit. An exten ately after germination. The endophytic system first sive endophytic system (see chapter 11) interacts develops within the host branch. Oftentimes, the only physiologically with the host to obtain needed evidence of infection is swelling of the tissues near the resources (water, minerals, and photosynthates); and infection site (Scharpf 1967). After 1 to 3 years, the first the shoots provide regulatory and reproductive func shoots are produced (table 2.1). All shoots arise from tions. Beyond specialization of their morphology (Le., the endophytic system and thus are root-borne shoots their leaves are reduced to scales), the dwarf mistle (Groff and Kaplan 1988). In emerging shoots, the toes also show peculiarities of their structure that leaves of adjacent nodes overlap and conceal the stem. reflect their phylogenetic relationships with other As the internodes elongate, stem segments become mistletoes and illustrate a high degree of specialization visible; but the shoot apex remains tightly enclosed by for the parasitic habit. From Arceuthobium globosum, newly developing leaf primordia (fig. 10.lA). Two the largest described species with shoots 70 cm tall oppositely arranged leaves, joined at their bases, occur and 5 cm in diameter, toA. -

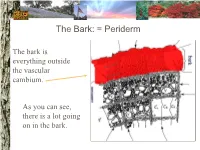

The Bark: = Periderm

The Bark: = Periderm The bark is everything outside the vascular cambium. As you can see, there is a lot going on in the bark. The Bark: periderm: phellogen (cork cambium): The phellogen is the region of cell division that forms the periderm tissues. Phellogen development influences bark appearance. The Bark: periderm: phellem (cork): Phellem replaces the epidermis as the tree increases in girth. Photosynthesis can take place in some trees both through the phellem and in fissures. The Bark: periderm: phelloderm: Phelloderm is active parenchyma tissue. Parenchyma cells can be used for storage, photosynthesis, defense, and even cell division! The Bark: phloem: Phloem tissue makes up the inner bark. However, it is vascular tissue formed from the vascular cambium. The Bark: phloem: sieve tube elements: Sieve tube elements actively transport photosynthates down the stem. Conifers have sieve cells instead. The cambium: The cambium is the primary meristem producing radial growth. It forms the phloem & xylem. The Xylem (wood): The xylem includes everything inside the vascular cambium. The Xylem: a growth increment (ring): The rings seen in many trees represent one growth increment. Growth rings provide the texture seen in wood. The Xylem: vessel elements: Hardwood species have vessel elements in addition to trachieds. Notice their location in the growth rings of this tree The Xylem: fibers: Fibers are cells with heavily lignified walls making them stiff. Many fibers in sapwood are alive at maturity and can be used for storage. The Xylem: axial parenchyma: Axial parenchyma is living tissue! Remember that parenchyma cells can be used for storage and cell division. -

Ultrastructural Study on the Formation of Sclereids in the Floating Leaves of Nymphoides Coreana and Nuphar Schimadai

Kuo-HuangBot. Bull. Acad. et al. Sin. — Sclereids(2000) 41: in 283-291Nymphoides and Nuphar 283 Ultrastructural study on the formation of sclereids in the floating leaves of Nymphoides coreana and Nuphar schimadai Ling-Long Kuo-Huang1,2, Su-Hwa Chen1, and Shiang-Jiuun Chen1 1 Department of Botany, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China (Received December 29, 1999; Accepted April 14, 2000) Abstract. The formation of star-shaped sclereids in the floating leaves of Nymphoides coreana and Nuphar schimadai was studied microscopically. These foliar sclereids were associated with the aerenchyma and found as the form of idioblast. The outer surface of mature sclereids was smooth in Nymphoides, but with many prismatic calcium oxalate crystals in Nuphar. However, the early morphogenesis of these two kinds of sclereids was similar. The sclereid initials were distinguished from the neighboring cells by their distinctly large nucleus. The expanding sclereid initials were constrained by the neighboring cells. Crystal formation in young sclereids of Nuphar started near the cessation of sclereid expansion. The crystals were bounded by crystal sheath and located in crystal chambers between the primary cell wall and plasma membrane. Calcium antimonate precipitates were found, especially on the crystal sheaths as well as between the plasma membrane and the primary cell walls. The crystal chambers have a paracrystalline appearance connected with the crystal sheath and the plasma membrane. After formation of crystals, the secondary wall was deposited and then the crystals became embedded between the primary and secondary walls. The possible functions of the foliage sclereids and the plans for further investigation are discussed. -

Epiparasitism in Phoradendron Durangense and P. Falcatum (Viscaceae) Clyde L

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 27 | Issue 1 Article 2 2009 Epiparasitism in Phoradendron durangense and P. falcatum (Viscaceae) Clyde L. Calvin Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, California Carol A. Wilson Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, California Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Calvin, Clyde L. and Wilson, Carol A. (2009) "Epiparasitism in Phoradendron durangense and P. falcatum (Viscaceae)," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 27: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol27/iss1/2 Aliso, 27, pp. 1–12 ’ 2009, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden EPIPARASITISM IN PHORADENDRON DURANGENSE AND P. FALCATUM (VISCACEAE) CLYDE L. CALVIN1 AND CAROL A. WILSON1,2 1Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, California 91711-3157, USA 2Corresponding author ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Phoradendron, the largest mistletoe genus in the New World, extends from temperate North America to temperate South America. Most species are parasitic on terrestrial hosts, but a few occur only, or primarily, on other species of Phoradendron. We examined relationships among two obligate epiparasites, P. durangense and P. falcatum, and their parasitic hosts. Fruit and seed of both epiparasites were small compared to those of their parasitic hosts. Seed of epiparasites was established on parasitic-host stems, leaves, and inflorescences. Shoots developed from the plumular region or from buds on the holdfast or subjacent tissue. The developing endophytic system initially consisted of multiple separate strands that widened, merged, and often entirely displaced its parasitic host from the cambial cylinder. -

Anatomy of the Underground Parts of Four Echinacea-Species and of Parthenium Integrifolium

Scientia Pharmaceutica (Sci. Pharm.) 69, 237-247 (2001) O Osterreichische Apotheker-Verlagsgesellschaft m.b.H., Wien, Printed in Austria Anatomy of the underground parts of four Echinacea-species and of Parthenium integrifolium R. Langer Institute of Pharmacognosy, University of Vienna Center of Pharmacy, Althanstrasse 14, A - 1090 Vienna, Austria Improved descriptions and detailed drawings of the most important anatomical characters of the roots of Echinacea purpurea (L.) MOENCH,E. angustifolia DC., E. pallida (NuTT.) NUTT.,and of Parfhenium integrifolium L. are presented. The anatomy of the rhizome of E. purpurea, which was detected in commercial samples, and of the root of E. atrorubens NUTT., another known adulteration for pharmaceutically used Echinacea-species, is documented for the first time. The possibilities and limitations of the identification by means of microscopy are discussed. The anatomical differences between the roots of E. angustifolia, E. pallida and E. atrorubens are not sufficient for differentiation, however, root and rhizome of E. purpurea and the root of Parthenium integrifolium appear well characterized. Because of the highly similar anatomy the microscopic proof of identity and purity of crude drugs of Echinacea must be done with uncomminuted material and the examination of cross sections. (Keywords: Echinacea angustifolia, Echinacea atrorubens, Echinacea pallida, Echinacea purpurea, Parthenium integrifolium, Asteraceae, microscopy, anatomy, identification) 1. Introduction The first, and for a long period only, detailed anatomical descriptions of the underground parts of Echinacea were published at the beginning of the last century', '. Due to later changes in the taxonomy within the genus Echinacea, unfortunately the plant sources for these descriptions remain unclear. The increasing interest in Echinacea and the adulterations that had been observed frequently caused Heubl et aL3 in the late eighties to examine the roots of E. -

Response of Avocado Pericarp Tissue to Mechanical Injury

Proc. of Second World Avocado Congress 1992 pp. 485-488 Response of Avocado Pericarp Tissue to Mechanical Injury C. A. Schroeder Dept. of Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90024, USA Abstract. Mechanical injury to avocado (Persea americana Mill.) pericarp will initiate a meristem and the production of periderm. Injury to tissues deep within the pericarp results in cellular differentiation of parenchyma with various degrees of cell wall thickening. Sclereid-like cells with thick, lignified walls and prominent pits can be formed in tissue normally occupied by thin-walled, oil-filled parenchyma. The unique growth and increase in volume of avocado fruit is characterized by continuous cell division in the pericarp tissue from pollination until fruit maturity. Shortly following fruit set, the parenchymatous cells which comprise the major tissue of the pericarp attain a diameter of approximately 50 //m and then undergo mitosis (Schroeder, 1953). Thus cell size is fairly constant and uniform throughout the fleshy pericarp. Larger fruit therefore have more cells than smaller fruit upon reaching maturity. Mitotic activity throughout the pericarp tissue at all times from anthesis to full fruit size is reflected in the high respiratory behavior of the fruit tissue, which is comparable to that of meristematic tissues in general. One can expect meristematic activity in the pericarp tissue at any point in time during fruit development. This has been demonstrated by the successful grafting of nearly mature avocado fruit. Cutting through the thick pericarp of adjacent fruit and holding these together along the cut plane eventually results in development of meristem tissue on the cut surfaces and the union of tissues between the two fruit (Schroeder ef a/., 1959). -

Phloem Structure and Development in Illicium Parviflorum, a Basal Angiosperm Shrub Authors

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/326322; this version posted June 1, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Article title: 2 Phloem structure and development in Illicium parviflorum, a basal angiosperm shrub 3 Authors: 4 Juan M. Losada1,2* and N. Michele Holbrook1,2 5 Affiliations: 6 1Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University. 16 Divinity Av., 7 Cambridge, MA, 02138, USA. 8 2Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University. 1300 Centre St., Boston, MA, 02130, USA. 9 *Author for correspondence. 10 Phone: + 1 (617) 384 5631 11 E-mail: [email protected] 12 13 WORD AND FIGURE COUNTS: 14 Total word count: 5,882 15 Introduction: 835 16 Materials and Methods: 1,530 17 Results: 1,412 18 Discussion: 1,939 19 Number of color figures: 8 20 Supporting information figures: 2 21 22 23 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/326322; this version posted June 1, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 24 SUMMARY 25 Recent studies in canopy-dominant trees revealed a structure-function scaling of the 26 phloem. However, whether axial scaling is conserved in woody plants of the understory, the 27 environments of most basal-grade angiosperms, remains mysterious. We used seedlings 28 and adult plants of the shrub Illicium parviflorum to explore the anatomy and physiology of 29 the phloem in their aerial parts, and possible changes through ontogeny. -

Getting Chemicals Into Trees Without Spraying

Urban Forestry NR/FF/020 (pr) Getting Chemicals Into Trees Without Spraying Michael Kuhns, Forestry Extension Specialist This fact sheet provides an overview of injection, or phellogen that makes cork to thicken the outer bark, implantation, and other ways to get chemicals, mainly phloem that conducts food through the tree from where pesticides, into trees. Many techniques and systems it is stored or made to where it is being used (all of these exist and some are very good, some are good in some tissues together make up the bark), vascular cambium situations, and some are ineffective or bad for trees. that divides rapidly to make new phloem and xylem cells, This fact sheet addresses all of these. and xylem or wood. Xylem includes an outer layer called the sapwood that conducts mostly water and minerals from the roots to the canopy, and an inner layer called the Chemicals are applied to trees for many reasons. heartwood that is aged sapwood that has died and has lost Insecticides repel or kill damaging insects, fungicides its ability to conduct water but still adds strength. treat or prevent fungal diseases, nutrients and plant growth regulators affect growth, and herbicides kill trees or prevent sprouting after tree removal. Spraying is the most typical way to apply these chemicals. It is fast, uses readily available equipment, and is understood. The Phellem (Cork Phellogen down side of spraying is that much of the chemical being or Outer Bark) Phloem applied is wasted, either to drift, run off, or because it can not be applied precisely to where it is needed in the tree. -

Sclereid Distribution in the Leaves of Pseudotsuga Under Natural and Experimental Conditions Author(S): Khalil H

Sclereid Distribution in the Leaves of Pseudotsuga Under Natural and Experimental Conditions Author(s): Khalil H. Al-Talib and John G. Torrey Source: American Journal of Botany, Vol. 48, No. 1 (Jan., 1961), pp. 71-79 Published by: Botanical Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2439597 . Accessed: 19/08/2011 13:16 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Botanical Society of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Botany. http://www.jstor.org January, 1961] AL-TALIB AND TORREY-SCLEREID DISTRIBUTION 71 SMITH, G. H. 1926. Vascular anatomyof Ranalian flowers. Aquilegia formosav. truncata and Ranunculus repens. I. Ranunculaceae. Bot. Gaz. 82: 1-29. Univ. California Publ. Bot. 25: 513-648. 1928. Vascular anatomy of Ranalian flowers. II. TUCKER, SHIRLEY C. 1959. Ontogeny of the inflorescence Ranunculaceae (continued), Menispermaceae,Calycan- and the flowerin Drimys winteri v. chilensis. Univ. thaceae, Annonaceae. Bot. Gaz. 85: 152-177. California Publ. Bot. 30: 257-335. SNOW, MARY, AND R. SNOW. 1947. On the determination . 1960. Ontogeny of the floral apex of Micheiat of leaves. New Phytol. 46: 5-19.