Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PATH Underground Walkway

PATH Marker Signs ranging from Index T V free-standing outdoor A I The Fairmont Royal York Hotel VIA Rail Canada H-19 pylons to door decals Adelaide Place G-12 InterContinental Toronto Centre H-18 Victory Building (80 Richmond 1 Adelaide East N-12 Hotel D-19 The Hudson’s Bay Company L-10 St. West) I-10 identify entrances 11 Adelaide West L-12 The Lanes I-11 W to the walkway. 105 Adelaide West I-13 K The Ritz-Carlton Hotel C-16 WaterPark Place J-22 130 Adelaide West H-12 1 King West M-15 Thomson Building J-10 95 Wellington West H-16 Air Canada Centre J-20 4 King West M-14 Toronto Coach Terminal J-5 100 Wellington West (Canadian In many elevators there is Allen Lambert Galleria 11 King West M-15 Toronto-Dominion Bank Pavilion Pacific Tower) H-16 a small PATH logo (Brookfield Place) L-17 130 King West H-14 J-14 200 Wellington West C-16 Atrium on Bay L-5 145 King West F-14 Toronto-Dominion Bank Tower mounted beside the Aura M-2 200 King West E-14 I-16 Y button for the floor 225 King West C-14 Toronto-Dominion Centre J-15 Yonge-Dundas Square N-6 B King Subway Station N-14 TD Canada Trust Tower K-18 Yonge Richmond Centre N-10 leading to the walkway. Bank of Nova Scotia K-13 TD North Tower I-14 100 Yonge M-13 Bay Adelaide Centre K-12 L TD South Tower I-16 104 Yonge M-13 Bay East Teamway K-19 25 Lower Simcoe E-20 TD West Tower (100 Wellington 110 Yonge M-12 Next Destination 10-20 Bay J-22 West) H-16 444 Yonge M-2 PATH directional signs tell 220 Bay J-16 M 25 York H-19 390 Bay (Munich Re Centre) Maple Leaf Square H-20 U 150 York G-12 you which building you’re You are in: J-10 MetroCentre B-14 Union Station J-18 York Centre (16 York St.) G-20 in and the next building Hudson’s Bay Company 777 Bay K-1 Metro Hall B-15 Union Subway Station J-18 York East Teamway H-19 Bay Wellington Tower K-16 Metro Toronto Convention Centre you’ll be entering. -

The North York East LIP Strategic Plan and Report

The North York East LIP Strategic Plan and Report The North York East Strategic Plan has been developed around six areas of focus: Information & Outreach; Civic Engagement; Collaboration & Capacity Building; Language Training & Supports; Labour Market; and Health Services.Six working groups will be established to address these areas of focus. In- depth directions for each working group are outlined in the main body of this report Executive Summary In 2009, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), in partnership with the Ontario Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration, launched Local Immigration Partnership (LIP) projects throughout Ontario. LIPs were developed as research initiatives to identify ways to coordinate and enhance local service delivery to newcomers across the province, while promoting efficient use of resources. In October 2009, Working Women Community Centre entered an agreement with CIC to lead a LIP project in the North York East area of Toronto. The North York East LIP is located in the far north of the city, contained by Steeles Avenue to the north, Highway 401 to the south, Victoria Avenue East to the east and the Don Valley River to the west. The area population is almost 80,000, 70% of which are immigrants to Canada. A major priority for the North York East LIP project was to root its research in the real-life experiences of local newcomers and local community organizations. In total, over 400 newcomers & immigrants, and over 100 service providers were consulted and engaged with to identify challenges, solutions and new directions for the settlement sector in the area. Methods of engagement for both newcomers and service providers included focus group research, key-informant interviews, community consultations and advisory panel workshops. -

Fam Altout Last YORK 200 ~Tyojtk

~~ ----.~ ~ciIudiq Fam altout lAST YORK 200 ~tyOJtk TODMORDENMILLS IIlust. courtesy of Todmorden Mills Heritage Museum EAST YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY FASCINATING FACTS ABOUT EAST YORK It..T~ Fascinating Facts About East York is one of the Iiii r numerous events at the Library in celebrating IAIT TORK 200 "East York 200". The list is very selective and we apolo gize for any oversights. Our aim is to take you through out the Borough and back through time to encounter a compendium of unique people, places and things. S. Walter Stewart Branch Area 1. Why is East York celebrating 200 years in 1996? In July of 1796, two brothers, Isaiah and Aaron Skinner were given permission to build a grist mill in the Don Valley, which they proceeded to do that winter. This began an industrial complex of paper mill, grist mill, brewery and distillery with later additions. In 1996, East York is celebrating 200 years of community. The Eastwood and Skinner mill, ca. 1877 from Torofilo IIIl1Slraled POSI & Prcsetl/. Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library 2. What is the area of East York? East York covers a physical area of2,149.7 hectares (8.3 square miles). Of the six municipalities comprising the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto, East York is the smallest in size, area-wise. 3. What are the symbols on the East York Coat of Arms and what do they signify? The British bulldog, from the Township of East York signifies the tenacity and courage of early settlers from Britain. The white rose of York is a symbol of peace from the settlers' homeland. -

Novae Res Urbis

FRIDAY, JUNE 16, 2017 REFUSAL 3 20 YEARS LATER 4 Replacing rentals Vol. 21 Stronger not enough No. 24 t o g e t h e r 20TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION NRU TURNS 20! AND THE STORY CONTINUES… Dominik Matusik xactly 20 years ago today, are on our walk selling the NRU faxed out its first City neighbourhood. But not the E of Toronto edition. For the developers. The question is next two decades, it covered whether the developers will the ups and downs of the city’s join the walk.” planning, development, and From 2017, it seems like municipal affairs news, though the answer to that question is a email has since replaced the fax resounding yes. machine. Many of the issues “One of the innovative the city cared about in 1997 still parts of the Regent Park resonate in 2017. From ideas for Revitalization,” downtown the new Yonge-Dundas Square city planning manager David to development charges along Oikawa wrote in an email the city’s latest subway line and to NRU, “was the concept of trepidations about revitalizing using [condos] to fund the Regent Park. It was an eventful needed new assisted public year. housing. A big unknown at The entire first edition of Novæ Res Urbis (2 pages), June 16, 1997 Below are some headlines from the time was [whether] that NRU’s first year and why these concept [would] work. Would issues continue to captivate us. private home owners respond to the idea of living and New Life for Regent Park investing in a mixed, integrated (July 7, 1997) community? Recently, some condo townhouses went on sale In 1997, NRU mused about the in Regent Park and were sold future of Regent Park. -

2018 Minutes of the Convention

DRAFT – FOR APPROVAL AT 2019 CONVENTION ONTARIO HORTICULTURAL ASSOCIATION ANNUAL MEETING, July 27-29, 2018 Ambassador Hotel Kingston “Shore to Shield” FRIDAY, JULY 27, 2018 Registration desk and vendors’ area were open before the start of the convention for delegates to visit. An early bird draw was held prior to the start of today’s session. The meeting opened at 9:00 a.m. in the Ambassador Ballroom, Ambassador Hotel. Convention Theme: “Shore to Shield” OPENING CEREMONIES: The Town Crier opened up the convention and provided a proclamation. The Officers of the Ontario Horticultural Association were introduced to the membership present in the Ambassador Ballroom. The membership present sang the Canadian National Anthem. Master of Ceremonies: Penny Stewart, District 3 Director, welcomed everyone to District 3 and the beautiful Kingston area. Introduction of Dignitaries: Penny introduced our special guests and dignitaries to the 112th Convention. Greetings were received from Mayor Brian Paterson and Shawn LaPalm, Cooperators. MPP, Ian Arthur, Minister Ernie Hardeman from OMAFRA and Denis Flanigan sent their best wishes as they were not able to attend. OHA Convention Opening: Rose Odell, OHA President opened the 112th OHA Convention. Land Acknowledgement Statement: Rose read the Land Acknowledgement Statement on behalf of the OHA “The land we meet upon today is the traditional land of the Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee Territory of this district. We give thanks for them and for the land upon which we meet.” OHA PRESIDENT’S WELCOME: Rose welcomed the Dignitaries, Officers, District Directors, and Past Presidents of the Ontario Horticultural Association. Rose wished everyone a weekend of learning, sharing, and meeting new people. -

Demographic Change in Toronto's Neighbourhoods

DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE IN TORONTO’S NEIGHBOURHOODS: Meeting community needs across the life span June, 2017 ABOUT SOCIAL PLANNING TORONTO Social Planning Toronto is a non-profit, charitable community organization that works to improve equity, social justice and quality of life in Toronto through community capacity building, community education and advocacy, policy research and analysis, and social reporting. Social Planning Toronto is committed to building a “Civic Society” one in which diversity, equity, social and economic justice, interdependence and active civic participation are central to all aspects of our lives - in our families, neighbourhoods, voluntary and recreational activities and in our politics. To find this report and learn more about Social Planning Toronto, visit socialplanningtoronto.org. DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE IN TORONTO’S NEIGHBOURHOODS: Meeting community needs across the life span © Social Planning Toronto ISBN: 978-1-894-199-39-1 Published in Toronto June, 2017 by Social Planning Toronto 2 Carlton St. Suite 1001 Toronto, ON M5B 1J3 This report was proudly produced with unionized labour. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS REPORT AUTHORS FUNDING SUPPORT Yeshewamebrat Desta Our thanks to our key funders, the City of Beth Wilson Toronto and the United Way Toronto & York Region. GIS MAPPING AND RESEARCH SUPPORT Dahab Ibrahim Beth Wilson REPORT LAYOUT AND DESIGN Carl Carganilla Ravi Joshi SOCIAL PLANNING TORONTO | 1 OVERVIEW Throughout 2017, Social Planning Toronto will be producing a series of reports highlighting newly released 2016 Census data from Statistics Canada and its significance for Toronto and its communities. Our first report, Growth and Change in Toronto’s Neighbourhoods, released in February focused on population growth and density in Toronto over the past five years and the implications for creating inclusive communities across the city. -

Bellcore Letter

Bellcore Letter Tcx Recipients of North American Numbering Plan Information. EnlitJed~ Unrestricted From: R. R. Conners,Director -North AmericanNumbering Plan Administration A1Im8d This IL provides industry notification of the impending split of the 416 NPA. (Includes safety liability disclaimer (if applicablc), ordering information, originator's signatu~ information) We have been advised by Bell Canada that substantial telephone number growth in the Toronto area necessitatessplitting the existing 416 NPA (area code) and the simultaneous introduction of a new 905 NPA Both NPAs will have interchangeablecentral office codes (i.e., the second digit of a central office code may be any digit 0-9). The new 905 NPA will serve the area surrounding Metro Toronto and will include cities such as Mississauga, Hamilton, Oshawa, and Niagara Falls. The 416 NPA will continue to serve the six boroughs that comprise Metro Toronto (i.e., Toronto, Scarborough,York, North York, East York, and Etobicoke). The split of the 416 NPA is scheduled for 2:00 AM Eastern Standard Time., Saturday, October 2,1993. There will be a permissive dialing period starting 2:00 AM Eastern Standard Time, Saturday, October 2, 1993 and ending at 2:00 AM Eastern Daylight SaVingsTime, Saturday March 26, 1994. During the permissive dialing period either 416 or 905 will be acceptable in a dialed number terminating in the new NPA. After the permissive period, calls dialed with incorrect NPA codes will be routed to intercept. Switching systemsin the new 9Or::!A"Will begin transmitting "905" in the calling number Automatic Number Identification (ANI) on October 1, 1992.1'" All ANI changeswill be completed by January 1, 1994. -

CAMH MONITOR METADATA USER's Eguide

CAMH MONITOR 2018 METADATA USER’S eGUIDE Centre for Addiction & Mental Health https://www.camh.ca/camh-monitor CAMH Monitor 2018 Metadata User’s eGuide Anca R. Ialomiteanu Hayley A. Hamilton Robert E. Mann 2019 Centre for Addiction & Mental Health https://www.camh.ca/camh-monitor CAMH Monitor 2018: Metadata User’s eGuide ISBN: 978-1-77114-429-2 (PDF) / (Digital) ISBN: 978-1-77114-428-5 (HTML) / (Online resource) Copyright ©2019 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Individuals and school or health organizations are invited to photocopy, in part or in whole, the contents of this report. Citation is appreciated. For information on other Centre for Addiction and Mental Health publications, or to place an order, please contact: Sales and Distribution Centre for Addiction and Mental Health 33 Russell Street Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 2S1 Tel.: 1 800 661-1111 or 416 595-6059 in Toronto E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.camh.ca Suggested Citation: Ialomiteanu, A.R., Hamilton, H.A. & Mann R.E. (2019). CAMH Monitor 2018: Metadata User’s eGuide. Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Available at: https://www.camh.ca/camh-monitor Table of Contents 1. Background ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. The CAMH Monitor Surveillance Program (1996-ongoing) ......................... 4 1.2. CAMH Monitor and Earlier Surveys .............................................................. 4 2. CAMH Monitor 2018 Sample Design ........................................................................... -

Government 99

Government 99 3.4 Electoral districts, voters on the list, votes polled and names and addresses of members of the House of Commons as elected at the thirty-first general election. May 22, 1979 (continued) Province and Popu Voters Total Votes Nameof member Postal address Party electoral district lation. on votes polled affili Census list polled by ation' 1976 (incl. member rejec tions) ONTARIO (concluded) Mississauga North 138,576 85,630 68,969 30,531 A.Jupp Mississauga PC Mississauga South 111,441 67,902 55,018 26,802 D. Blenkarn Mississauga PC Nepean — Carleton 108,336 73,725 61,787 36,717 W. Baker Nepean PC Niagara Falls 81,908 54,567 40,634 16,916 J. Froese Niagara-on-the-Lake PC Nickel Belt 90,799 53,320 41,097 17,772 J. Rodriguez Capreol NDP Nipissing 69,159 44,556 34,031 15,184 J.-J. Blais North Bay Lib. Northumberland 75,974 50,776 38,028 22,536 G. Hees Cobourg PC Ontario 87,803 60,797 50,216 22,583 S. Fennell Pickering PC Oshawa 107,023 71,992 57,034 29,090 E. Broadbent' Oshawa NDP Ottawa-Carleton 119,748 81,455 69,205 33,972 J.-L. Pepin Ottawa Lib. Ottawa Centre 83,371 63,400 49,579 19,758 J. Evans Ottawa Lib. Ottawa-Vanier 84,309 57,970 44,766 28,098 J.-R. Gauthier Ottawa Lib. Ottawa West 95,479 67,302 55,419 24,981 K. Binks Ottawa PC Oxford 85,337 56,376 42,929 23,592 B. -

Members to Vote on Bylaw Change That Realign RNAO's Chapter Boundaries

Members to vote on bylaw change that realign RNAO’s chapter boundaries t a meeting of RNAO’s board of directors held Feb. 22, 2020, and following consultation with members at the Feb. 21, 2020 assembly meeting, a motion was passed to approve a proposed amendment to ABylaw 3.0. The board proposal would alter chapter and region boundaries so they follow boundaries of Ontario’s provincial electoral ridings. The proposed change is designed to better position how RNAO’s membership is organized geographically across the province with the political activities of the association. Ontario changed its riding boundaries ahead of the 2018 provincial election so its ridings were more closely aligned with federal ridings, which changed for the 2015 federal election. The board believes the proposed change would continue to foster and strengthen relationships members and chapter executives, in particular, have created with MPPs and MPs and facilitate future political action at the municipal level where responsibility for so many issues related to determinants of health lies. Currently, ridings in some chapters crossover into neighbouring chapters, which can lead to confusion and splits responsibility for organizing political action events among chapters. Realigning chapters would also provide members with the opportunity to create stronger relationships with their community leaders and local media. Under the proposed amendment, no new regions would be created; however, chapter boundary changes will have implications for region boundaries thereby triggering the need for the bylaw change. Four new chapters would be created: York East, York West, Mississauga and Brampton. The proposed realignment would add four consultation representatives to RNAO’s network of voting delegates. -

Heading Down the Back Stretch, It's a Horserace for Toronto Mayor with Edge to Smitherman

Heading down the Back Stretch, It’s a Horserace for Toronto Mayor with Edge to Smitherman Smitherman (31% +8) and Ford (30% +2) Tied on Topline Vote Preference with Pantalone (11% +1) and Rossi (4% -3) Trailing… But Among those Committed to Go Out and Vote it’s Smitherman (38% +8) Leading Ford (32% +3), Pantalone (15% +1) and Rossi (3% -3) Public Release Date: Wednesday, October 13, 2010, 4:00 PM EDT Ipsos Reid is Canada's market intelligence leader and the country’s leading provider of public opinion research. With operations in eight cities, Ipsos Reid employs more than 300 research professionals and support staff in Canada. The company has the biggest network of telephone call centres in Canada, as well as the largest pre-recruited household and on-line panels. Ipsos Reid’s Canadian marketing research and public affairs practices are staffed with seasoned research consultants with extensive industry-specific backgrounds, offering the premier suite of research vehicles in Canada—including the Ipsos Trend Report, the leading source of public opinion in the country—all of which provide clients with actionable and relevant information. Ipsos Reid is an Ipsos company, a leading global survey-based market research group. To learn more, visit www.ipsos.ca For copies of other news releases, please visit http://www.ipsos-na.com/news/ © Ipsos Reid Washington λ New York λ Chicago λ Minneapolis λ Seattle λ San Francisco Vancouver λ Edmonton λ Calgary λ Winnipeg λ Toronto λ Ottawa λ Montreal Heading down the Back Stretch, It’s a Horserace for Toronto -

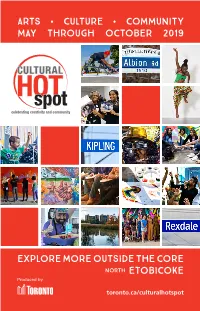

2019 Cultural Hotspot Program Guide

arts • culture • community May through October 2019 Explore more outside the core north Etobicoke toronto.ca/culturalhotspot Program Sponsors 01 7 August 2017 Printed colours 186 Large logo: over 60mm wide File name tim_hortons_master_logo Client Tim Hortons Project Master Logo Artworker RS Warwick Building, Avonmore Road London, W14 8HQ, United Kingdom +44 (0)20 8994 7190 Small logo: 30–60mm wide Minimum size of small logo Maximum size of small logo 30mm wide 60mm wide Contents Welcome to the 2019 Cultural Hotspot ��������������������������������������1 Experience the 2019 Cultural Hotspot����������������������������������������2 About the Cultural Hotspot �������������������������������������������������������3 North Etobicoke – This Spot is Hot! �������������������������������������������4 Signature Projects ����������������������������������������������������������������6 SPARK Projects ....................................................................16 Community Projects �����������������������������������������������������������28 Toronto Public Library ........................................................36 HOT Eats ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������39 Cultural Loops����������������������������������������������������������������������������39 Acknowledgements �������������������������������������������������������������������40 Community Partners & Supporters �������������������������������������������41 427 Map 409 Land Acknowledgement We acknowledge the land we are meeting