An Analysis of 17Th-Century Ceramics in Plymouth Colony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

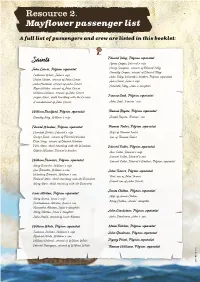

Resource 2 Mayflower Passenger List

Resource 2. Mayflower passenger list A full list of passengers and crew are listed in this booklet: Edward Tilley, Pilgrim separatist Saints Agnus Cooper, Edward’s wife John Carver, Pilgrim separatist Henry Sampson, servant of Edward Tilley Humility Cooper, servant of Edward Tilley Catherine White, John’s wife John Tilley, Edwards’s brother, Pilgrim separatist Desire Minter, servant of John Carver Joan Hurst, John’s wife John Howland, servant of John Carver Elizabeth Tilley, John’s daughter Roger Wilder, servant of John Carver William Latham, servant of John Carver Jasper More, child travelling with the Carvers Francis Cook, Pilgrim separatist A maidservant of John Carver John Cook, Francis’ son William Bradford, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Rogers, Pilgrim separatist Dorothy May, William’s wife Joseph Rogers, Thomas’ son Edward Winslow, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Tinker, Pilgrim separatist Elizabeth Barker, Edward’s wife Wife of Thomas Tinker George Soule, servant of Edward Winslow Son of Thomas Tinker Elias Story, servant of Edward Winslow Ellen More, child travelling with the Winslows Edward Fuller, Pilgrim separatist Gilbert Winslow, Edward’s brother Ann Fuller, Edward’s wife Samuel Fuller, Edward’s son William Brewster, Pilgrim separatist Samuel Fuller, Edward’s Brother, Pilgrim separatist Mary Brewster, William’s wife Love Brewster, William’s son John Turner, Pilgrim separatist Wrestling Brewster, William’s son First son of John Turner Richard More, child travelling with the Brewsters Second son of John Turner Mary More, child travelling -

Girls on the Mayflower

Girls on the Mayflower http://members.aol.com/calebj/girls.html (out of circulation; see: https://www.prettytough.com/girls-on-the-mayflower/ http://mayflowerhistory.com/girls https://itchyfish.com/oceanus-hopkins-the-child-born-aboard-the-mayflower/ ) While much attention is focused on the men who came on the Mayflower, few people realize and take note that there were eleven girls on board, ranging in ages from less than a year old up to about sixteen or seventeen. William Bradford wrote that one of the Pilgrim's primary concerns was that the "weak bodies" of the women and girls would not be able to handle such a long voyage at sea, and the harsh life involved in establishing a new colony. For this reason, many girls were left behind, to be sent for later after the Colony had been established. Some of the daughters left behind include Fear Brewster (age 14), Mary Warren (10), Anna Warren (8), Sarah Warren (6), Elizabeth Warren (4), Abigail Warren (2), Jane Cooke (8), Hester Cooke (1), Mary Priest (7), Sarah Priest (5), and Elizabeth and Margaret Rogers. As it would turn out however, the girls had the strongest bodies of them all. No girls died on the Mayflower's voyage, but one man and one boy did. And the terrible first winter, twenty-five men (50%) and eight boys (36%) got sick and died, compared to only two girls (16%). So who were these girls? One of them was under the age of one, named Humility Cooper. Her father had died, and her mother was unable to support her; so she was sent with her aunt and uncle on the Mayflower. -

Medieval Pottery from Romsey: an Overview

Proc. Hampshire Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 67 (pt. II), 2012, 323–346 (Hampshire Studies 2012) MEDIEVAL POTTERY FROM ROMSEY: AN OVERVIEW By BEN JERVIS ABSTRACT is evidence of both prehistoric and Roman occupation, but this paper will deal only with This paper summarises the medieval pottery recovered the medieval archaeology, from the mid-Saxon from excavations undertaken by Test Valley Archae- period to the 16th century. ological Trust in Romsey, Hampshire from the Several excavations took place between the 1970’s–1990’s. A brief synthesis of the archaeology of 1970’s–90’s in the precinct of Romsey Abbey Romsey is presented followed by a dated catalogue of (see Scott 1996). It has been suggested on the pottery types identified, including discussions of the basis of historical evidence and a series fabric, form and wider affinities. The paper concludes of excavated, early, graves that the late Saxon with discussions of the supply of pottery to Romsey in abbey was built on the site of an existing eccle- the medieval period and also considers ceramic use siastical establishment, possibly a minster in the town. church (Collier 1990, 45; Scott 1996, 7). The foundation of the nunnery itself can be dated to the 10th century (Scott 1996, 158), but it INTRODUCTION was evacuated in AD 1001, due to the threat of Danish attack, being re-founded later in The small town of Romsey has been the focus the 11th century. The abbey expanded during of much archaeological excavation over the last the Norman period, with the building of the 30–40 years, but very little has been published choir and nave (Scott 1996, 7). -

Aldens' Progress

The Alden House Historic Site, P. O. Box 2754, Duxbury, Massachusetts 02331 Aldens’ Progress News of the Alden Kindred of America, Inc. Spring 2009 SPEAKING FOR OURSELVES Tom McCarthy, Historian of the Alden Kindred of America must be the very best site associated with a person, event, or development of national (as opposed to local) historic significance. For the Alden House the designation means a “promotion” from the ranks of the more than 80,000 sites on the National Register of Historic Places, where it has been listed since 1978. But the Original Alden Homestead Site had not even The Alden House been listed on the Register. The National Park Historic Site Service runs the programs that confer both 2009 Calendar historical designations under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. W Museum opens: May 18 In addition to recognizing that no other historic Speak for Thyself: June 20 site was so prominently associated with Mayflower passengers, the National Historic Duxbury Free Day: July 11 fter lunch at our annual reunion on August Landmarks subcommittee of the National Park Annual Meeting & A 1, 2009 the Alden Kindred and the Town System Advisory Board endorsed four specific National Historic of Duxbury will accept plaques from the National claims to historical significance. First, the national Landmark Award: August 1 Park Service designating the Alden House and cultural impact of Alden descendant Henry Alden Open: September 26 Original Alden Homestead Site as the John and Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1858 poem The Priscilla Alden Family Sites National Historic Courtship of Miles Standish made the surviving Museum closes: October 12 Landmark. -

Recovering Jane Goodwin Austin

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-11-2015 "So Long as the Work is Done": Recovering Jane Goodwin Austin Kari Holloway Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Miller, Kari Holloway, ""So Long as the Work is Done": Recovering Jane Goodwin Austin." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2015. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/153 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “SO LONG AS THE WORK IS DONE”: RECOVERING JANE GOODWIN AUSTIN by KARI HOLLOWAY MILLER Under the Direction of Janet Gabler-Hover, PhD ABSTRACT The American author Jane Goodwin Austin published 24 novels and numerous short stories in a variety of genres between 1859 and 1892. Austin’s most popular works focus on her Pilgrim ancestors, and she is often lauded as a notable scholar of Puritan history who carefully researched her subject matter; however, several of the most common myths about the Pilgrims seem to have originated in Austin’s fiction. As a writer who saw her work as her means of entering the public sphere and enacting social change, Austin championed women and religious diversity. The range of Austin’s oeuvre, her coterie of notable friendships, especially amongst New England elites, and her impact on American myth and culture make her worthy of in-depth scholarly study, yet, inexplicably, very little critical work exists on Austin. -

European Journal of American Studies, 14-3 | 2019 Feminizing a Colonial Epic: on Spofford’S “Priscilla” 2

European journal of American studies 14-3 | 2019 Special Issue: Harriet Prescott Spofford: The Home, the Nation, and the Wilderness Feminizing a Colonial Epic: On Spofford’s “Priscilla” Daniela Daniele Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/14976 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.14976 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Daniela Daniele, “Feminizing a Colonial Epic: On Spofford’s “Priscilla””, European journal of American studies [Online], 14-3 | 2019, Online since 11 November 2019, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/ejas/14976 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.14976 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License Feminizing a Colonial Epic: On Spofford’s “Priscilla” 1 Feminizing a Colonial Epic: On Spofford’s “Priscilla” Daniela Daniele 1. Recovering a Romantic Realist 1 Harriet Elizabeth Prescott Spofford often responded to the requests of many editors to anonymously contribute stories to Boston “family” story-papers in the late fifties, well aware that it was not “her first inclination to write in a hasty, commercial manner” (Salmonson xviii). Few of those stories bore her name and, in producing them, she apparently seemed to follow Henry James’s patronizing advice to abandon “the ideal descriptive style” and “study the canon of the so-called realist school,” because “the public taste [had] changed” (James, “rev. of Harriet Prescott Spofford,” 269, 272). Later in the century, as an author of local color sketches, -

William Bradford's Life and Influence Have Been Chronicled by Many. As the Co-Author of Mourt's Relation, the Author of of Plymo

William Bradford's life and influence have been chronicled by many. As the co-author of Mourt's Relation, the author of Of Plymouth Plantation, and the long-term governor of Plymouth Colony, his documented activities are vast in scope. The success of the Plymouth Colony is largely due to his remarkable ability to manage men and affairs. The information presented here will not attempt to recreate all of his activities. Instead, we will present: a portion of the biography of William Bradford written by Cotton Mather and originally published in 1702, a further reading list, selected texts which may not be usually found in other publications, and information about items related to William Bradford which may be found in Pilgrim Hall Museum. Cotton Mather's Life of William Bradford (originally published 1702) "Among those devout people was our William Bradford, who was born Anno 1588 in an obscure village called Ansterfield... he had a comfortable inheritance left him of his honest parents, who died while he was yet a child, and cast him on the education, first of his grand parents, and then of his uncles, who devoted him, like his ancestors, unto the affairs of husbandry. Soon a long sickness kept him, as he would afterwards thankfully say, from the vanities of youth, and made him the fitter for what he was afterwards to undergo. When he was about a dozen years old, the reading of the Scripture began to cause great impressions upon him; and those impressions were much assisted and improved, when he came to enjoy Mr. -

New England‟S Memorial

© 2009, MayflowerHistory.com. All Rights Reserved. New England‟s Memorial: Or, A BRIEF RELATION OF THE MOST MEMORABLE AND REMARKABLE PASSAGES OF THE PROVIDENCE OF GOD, MANIFESTED TO THE PLANTERS OF NEW ENGLAND IN AMERICA: WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE FIRST COLONY THEREOF, CALLED NEW PLYMOUTH. AS ALSO A NOMINATION OF DIVERS OF THE MOST EMINENT INSTRUMENTS DECEASED, BOTH OF CHURCH AND COMMONWEALTH, IMPROVED IN THE FIRST BEGINNING AND AFTER PROGRESS OF SUNDRY OF THE RESPECTIVE JURISDICTIONS IN THOSE PARTS; IN REFERENCE UNTO SUNDRY EXEMPLARY PASSAGES OF THEIR LIVES, AND THE TIME OF THEIR DEATH. Published for the use and benefit of present and future generations, BY NATHANIEL MORTON, SECRETARY TO THE COURT, FOR THE JURISDICTION OF NEW PLYMOUTH. Deut. xxxii. 10.—He found him in a desert land, in the waste howling wilderness he led him about; he instructed him, he kept him as the apple of his eye. Jer. ii. 2,3.—I remember thee, the kindness of thy youth, the love of thine espousals, when thou wentest after me in the wilderness, in the land that was not sown, etc. Deut. viii. 2,16.—And thou shalt remember all the way which the Lord thy God led thee this forty years in the wilderness, etc. CAMBRIDGE: PRINTED BY S.G. and M.J. FOR JOHN USHER OF BOSTON. 1669. © 2009, MayflowerHistory.com. All Rights Reserved. TO THE RIGHT WORSHIPFUL, THOMAS PRENCE, ESQ., GOVERNOR OF THE JURISDICTION OF NEW PLYMOUTH; WITH THE WORSHIPFUL, THE MAGISTRATES, HIS ASSISTANTS IN THE SAID GOVERNMENT: N.M. wisheth Peace and Prosperity in this life, and Eternal Happiness in that which is to come. -

Interim Report on the Preservation Virginia Excavations at Jamestown, Virginia

2007–2010 Interim Report on the Preservation Virginia Excavations at Jamestown, Virginia Contributing Authors: David Givens, William M. Kelso, Jamie May, Mary Anna Richardson, Daniel Schmidt, & Beverly Straube William M. Kelso Beverly Straube Daniel Schmidt Editors March 2012 Structure 177 (Well) Structure 176 Structure 189 Soldier’s Pits Structure 175 Structure 183 Structure 172 Structure 187 1607 Burial Ground Structure 180 West Bulwark Ditch Solitary Burials Marketplace Structure 185 Churchyard (Cellar/Well) Excavations Prehistoric Test Ditches 28 & 29 Structure 179 Fence 2&3 (Storehouse) Ludwell Burial Structure 184 Pit 25 Slot Trenches Outlines of James Fort South Church Excavations Structure 165 Structure 160 East Bulwark Ditch 2 2 Graphics and maps by David Givens and Jamie May Design and production by David Givens Photography by Michael Lavin and Mary Anna Richardson ©2012 by Preservation Virginia and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. All rights reserved, including the right to produce this report or portions thereof in any form. 2 2 Acknowledgements (2007–2010) The Jamestown Rediscovery team, directed by Dr. William this period, namely Juliana Harding, Christian Hager, and Kelso, continued archaeological excavations at the James Matthew Balazik. Thank you to the Colonial Williamsburg Fort site from 2007–2010. The following list highlights Foundation architectural historians who have analyzed the some of the many individuals who contributed to the project fort buildings with us: Cary Carson, Willie Graham, Carl during these -

Destination Plymouth

DESTINATION PLYMOUTH Approximately 40 miles from park, travel time 50 minutes: Turn left when leaving Normandy Farms onto West Street. You will cross the town line and West Street becomes Thurston Street. At 1.3 miles from exiting park, you will reach Washington Street / US‐1 South. Turn left onto US‐1 South. Continue for 1.3 miles and turn onto I‐495 South toward Cape Cod. Drive approximately 22 miles to US‐44 E (exit 15) toward Middleboro / Plymouth. Bear right off ramp to US‐44E, in less than ¼ mile you will enter a rotary, take the third exit onto US‐ 44E towards Plymouth. Continue for approximately 14.5 miles. Merge onto US‐44E / RT‐3 South toward Plymouth/Cape Cod for just a little over a mile. Merge onto US‐44E / Samoset St via exit 6A toward Plymouth Center. Exit right off ramp onto US‐ 44E / Samoset St, which ends at Route 3A. At light you will see “Welcome to Historic Plymouth” sign, go straight. US‐44E / Samoset Street becomes North Park Ave. At rotary, take the first exit onto Water Street; the Visitor Center will be on your right with the parking lot behind the building. For GPS purposes the mapping address of the Plymouth Visitor Center – 130 Water Street, Plymouth, MA 02360 Leaving Plymouth: Exit left out of lot, then travel around rotary on South Park Ave, staying straight onto North Park Ave. Go straight thru intersection onto Samoset Street (also known as US‐44W). At the next light, turn right onto US‐44W/RT 3 for about ½ miles to X7 – sign reads “44W Taunton / Providence, RI”. -

Notes on Cole's Hill

NOTES ON COLE’S HILL by Edward R. Belcher Pilgrim Society Note, Series One, Number One, 1954 The designation of Cole‟s Hill as a registered National Historic Landmark by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, was announced at the Annual Meeting of the Pilgrim Society on December 21, 1961. An official plaque will be placed on Cole‟s Hill. The formal application for this designation, made by the Society, reads in part: "... Fully conscious of the high responsibility to the Nation that goes with the ownership and care of a property classified as ... worthy of Registered National Historic Landmark status ... we agree to preserve... to the best of our ability, the historical integrity of this important part of our national cultural heritage ..." A tablet mounted on the granite post at the top of the steps on Cole‟s Hill bears this inscription: "In memory of James Cole Born London England 1600 Died Plymouth Mass 1692 First settler of Coles Hill 1633 A soldier in Pequot Indian War 1637 This tablet erected by his descendants1917" Cole‟s Hill, rising from the shore near the center of town and overlooking the Rock and the harbor, has occupied a prominent place in the affairs of the community. Here were buried the bodies of those who died during the first years of the settlement. From it could be watched the arrivals and departures of the many fishing and trading boats and the ships that came from time to time. In times of emergency, the Hill was fortified for the protection of the town. -

Nonsuch Palace

MARTIN BIDDLE who excavated Nonsuch ONSUCH, ‘this which no equal has and its Banqueting House while still an N in Art or Fame’, was built by Henry undergraduate at Pembroke College, * Palace Nonsuch * VIII to celebrate the birth in 1537 of Cambridge, is now Emeritus Professor of Prince Edward, the longed-for heir to the Medieval Archaeology at Oxford and an English throne. Nine hundred feet of the Emeritus Fellow of Hertford College. His external walls of the palace were excavations and other investigations, all NONSUCH PALACE decorated in stucco with scenes from with his wife, the Danish archaeologist classical mythology and history, the Birthe Kjølbye-Biddle, include Winchester Gods and Goddesses, the Labours of (1961–71), the Anglo-Saxon church and Hercules, the Arts and Virtues, the Viking winter camp at Repton in The Material Culture heads of many of the Roman emperors, Derbyshire (1974–93), St Albans Abbey and Henry VIII himself looking on with and Cathedral Church (1978, 1982–4, the young Edward by his side. The 1991, 1994–5), the Tomb of Christ in of a Noble Restoration Household largest scheme of political propaganda the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (since ever created for the English crown, the 1989), and the Church on the Point at stuccoes were a mirror to show Edward Qasr Ibrim in Nubia (1989 and later). He the virtues and duties of a prince. is a Fellow of the British Academy. Edward visited Nonsuch only once as king and Mary sold it to the Earl of Martin Biddle Arundel. Nonsuch returned to the crown in 1592 and remained a royal house until 1670 when Charles II gave the palace and its park to his former mistress, Barbara Palmer, Duchess of Cleveland.