NORMAL WINNERS: the STRATEGIES of STRONG CANDIDATES Ellen Gutman Galantucci a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Unive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

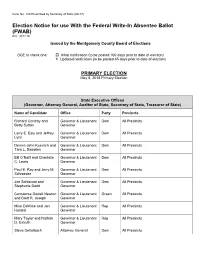

Election Notice for Use with the Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot (FWAB) R.C

Form No. 120 Prescribed by Secretary of State (09-17) Election Notice for use With the Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot (FWAB) R.C. 3511.16 Issued by the Montgomery County Board of Elections BOE to check one: Initial notification (to be posted 100 days prior to date of election) X Updated notification (to be posted 45 days prior to date of election) PRIMARY ELECTION May 8, 2018 Primary Election State Executive Offices (Governor, Attorney General, Auditor of State, Secretary of State, Treasurer of State) Name of Candidate Office Party Precincts Richard Cordray and Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Betty Sutton Governor Larry E. Ealy and Jeffrey Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Lynn Governor Dennis John Kucinich and Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Tara L. Samples Governor Bill O’Neill and Chantelle Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts C. Lewis Governor Paul E. Ray and Jerry M. Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Schroeder Governor Joe Schiavoni and Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Stephanie Dodd Governor Constance Gadell-Newton Governor & Lieutenant Green All Precincts and Brett R. Joseph Governor Mike DeWine and Jon Governor & Lieutenant Rep All Precincts Husted Governor Mary Taylor and Nathan Governor & Lieutenant Rep All Precincts D. Estruth Governor Steve Dettelbach Attorney General Dem All Precincts Dave Yost Attorney General Rep All Precincts Zack Space Auditor of State Dem All Precincts Keith Faber Auditor of State Rep All Precincts Kathleen Clyde Secretary of State Dem All Precincts Frank LaRose Secretary of State Rep All Precincts Rob Richardson Treasurer of State Dem All Precincts Sandra O’Brien Treasurer of State Rep All Precincts Robert Sprague Treasurer of State Rep All Precincts Paul Curry (Write-In) Treasurer of State Green All Precincts U.S. -

Candidate Details Printed: 3/8/2018 STATE of OHIO Attorney General Vote for 1 FTC 01/01/2019 05/08/2018 Dave Yost REP

Updated: 3/8/2018 CERTIFIED CANDIDATE LIST MAY 08, 2018 ELECTION RACES NOT PRESENTED IN BALLOT APPEARANCE ORDER STATE OF OHIO US Senator Vote For 1 FTC 01/01/2019 05/08/2018 Sherrod Brown DEM STATE OF OHIO US Senator Vote For 1 FTC 01/01/2019 05/08/2018 Melissa Ackison REP Don Elijah Eckhart REP Mike Gibbons REP Dan Kiley REP Jim Renacci REP STATE OF OHIO Governor/Lt Gov Vote For 1 FTC 01/01/2019 05/08/2018 Richard Cordray DEM Larry E. Ealy DEM Dennis John Kucinich DEM Bill O'Neill DEM Paul E. Ray DEM Joe Schiavoni DEM STATE OF OHIO Governor/Lt Gov Vote For 1 FTC 01/01/2019 05/08/2018 Mike DeWine REP Mary Taylor REP STATE OF OHIO Governor/Lt. Gov Vote For 1 FTC 01/01/2019 05/08/2018 Constance Gadell-Newton GRE R740.02 Candidate Details Printed: 3/8/2018 STATE OF OHIO Attorney General Vote For 1 FTC 01/01/2019 05/08/2018 Dave Yost REP STATE OF OHIO Attorney General Vote For 1 FTC 01/01/2019 05/08/2018 Steve Dettelbach DEM STATE OF OHIO Auditor of State Vote For 1 FTC 01/01/2019 05/08/2018 Zack Space DEM STATE OF OHIO Auditor of State Vote For 1 FTC 01/01/2019 05/08/2018 Keith Faber REP STATE OF OHIO Secretary of State Vote For 1 FTC 01/01/2019 05/08/2018 Frank LaRose REP STATE OF OHIO Secretary of State Vote For 1 FTC 01/01/2019 05/08/5018 Kathleen Clyde DEM STATE OF OHIO Treasurer of State Vote For 1 FTC 01/01/2019 05/08/2018 Sandra O'Brien REP Robert Sprague REP STATE OF OHIO Treasurer of State Vote For 1 FTC 01/01/2019 05/08/2018 Rob Richardson DEM R740.02 Candidate Details Printed: 3/8/2018 CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT 15 Rep to Congress -

Idaho Shows Strong Support for GNEP

Idaho shows strong support for GNEP Support for Idaho as a potential site for the Department of Energy's Global Nuclear Photo: Idaho mayors Energy Partnership (GNEP) project was abundant at the March 15 Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement (PEIS) scoping meeting. Turnout was considerable. Approximately 650 people participated in the event, and 132 speakers shared their opinions. The number attending was roughly double in size of the next-largest GNEP scoping meeting prior to Idaho Falls. Widespread support for the project was clear with approximately 95% of the speakers advocating the development of GNEP in Idaho or at Idaho National Laboratory. Throughout the evening, numerous private citizens and representatives of Idaho civic and business organizations provided compelling reasons why DOE should choose INL to Idaho Falls Mayor Jared Fuhriman was surrounded participate in the project - including the lab's history, current mission and resources. by 16 other mayors from Idaho as he read a joint statement that favored a critical GNEP role for INL. Political luminaries lined up to support GNEP. Spokesmen for the entire Idaho political delegation - all of Idaho's U.S. senators and congressmen, the governor, lieutenant governor, the state legislature, as well as 16 mayors and commissioners from 10 counties - stood up to read letters of support into the meeting record. The standing-room-only crowd included dozens of community leaders from counties surrounding INL. Among the key political figures represented were Sen. Larry Craig, Sen. Mike Crapo, Rep. Mike Simpson, Rep. Bill Sali, Gov. Butch Otter and mayors from across the state who offered written appeals to DOE to include INL as a vital element of GNEP. -

Sample Ballot General

SAMPLE BALLOT IDAHO GENERAL ELECTION TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 4, 2008 - NEZ PERCE COUNTY, IDAHO POLLS OPEN 8:00 A.M. TO 8:00 P.M. VOTERS LEGISLATIVE DISTRICT 7 PRECINCT POLLING PLACE Lewiston #20 ..................... Nez Perce County Fair Building Lewiston #1 ............................ Lewiston Community Center Lewiston #21 ..................... Nez Perce County Fair Building MUST BE A U.S. CITIZEN Lewiston #2 ............................ Lewiston Community Center Lewiston #22 ..................... Nez Perce County Fair Building Lewiston #3 .................................... Trinity Lutheran Church Lewiston #23 ..................... Nez Perce County Fair Building Lewiston #4 ............................ Lewiston Community Center Lewiston #24 ..................... Nez Perce County Fair Building Lewiston #5 .................... Woodworkers Local Lodge W364 Lewiston #25 ..................... Nez Perce County Fair Building Lewiston #6 ............................ Lewiston Community Center Lewiston #26 ..................... Nez Perce County Fair Building RESIDE IN THE COUNTY FOR Lewiston #7 .................................... Trinity Lutheran Church Culdesac #30 ........................ Culdesac Community Center Lewiston #8 .............................................. Nazarene Church Gifford #31...................................... Gifford Community Hall THIRTY (30) DAYS BEFORE THE ELECTION Lewiston #9 .............................................. Nazarene Church Hatwai #32 ..................... Woodworkers Local Lodge W364 Lewiston #10 -

Election Notice for Use with the Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot (Fwab) R.C

ELECTION NOTICE FOR USE WITH THE FEDERAL WRITE-IN ABSENTEE BALLOT (FWAB) R.C. 3511.16 Issued by the Delaware County Board of Elections BOE to check one: Initial notification (to be posted 100 days prior to date of election) Updated notification (to be posted 45 days prior to date of election) May 8, 2018 Primary Election (month, date, year, primary/general/special) All Offices Name of Candidate (Party) Office , District, Term Precincts RICHARD CORDRAY (D) and GOVERNOR AND LIEUTENANT All Precincts BETTY SUTTON (D) GOVERNOR 1 to be elected MIKE DEWINE (R) and Full Term Commencing 1/14/2019 JON HUSTED (R) LARRY E. EALY (D) and JEFFREY LYNN (D) CONSTANCE GADELL-NEWTON (G) and BRETT R. JOSEPH (G) DENNIS JOHN KUCINICH (D) and TARA L. SAMPLES (D) BILL O'NEILL (D) and CHANTELLE C. LEWIS (D) PAUL E. RAY (D) and JERRY M. SCHROEDER (D) JOE SCHIAVONI (D) and STEPHANIE DODD (D) MARY TAYLOR (R) and NATHAN D. ESTRUTH (R) STEVE DETTELBACH (D) ATTORNEY GENERAL All Precincts DAVE YOST (R) 1 to be elected Full Term Commencing 1/14/2019 KEITH FABER (R) AUDITOR OF STATE All Precincts ZACK SPACE (D) 1 to be elected Full Term Commencing 1/14/2019 KATHLEEN CLYDE (D) SECRETARY OF STATE All Precincts FRANK LAROSE (R) 1 to be elected Full Term Commencing 1/14/2019 SANDRA O'BRIEN (R) TREASURER OF STATE All Precincts ROB RICHARDSON (D) 1 to be elected ROBERT SPRAGUE (R) Full Term Commencing 1/14/2019 WRITE-IN PAUL CURRY (G) CRAIG BALDWIN (R) JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME All Precincts MICHAEL P. -

Election Notice for Use with the Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot (FWAB) R.C

Form No. 120 Prescribed by Secretary of State (09-17) Election Notice for use With the Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot (FWAB) R.C. 3511.16 Issued by the Mahoning County Board of Elections BOE to check one: Initial notification (to be posted 100 days prior to date of election) Updated notification (to be posted 45 days prior to date of election) MAY 8, 2018 PRIMARY ELECTION State Executive Offices (Governor, Attorney General, Auditor of State, Secretary of State, Treasurer of State) Name of Candidate Office Party Precincts Richard Cordray and Betty Governor and Lieutenant Democratic All Precincts Sutton Governor Larry E. Ealy and Jeffrey Governor and Lieutenant Democratic All Precincts Lynn Governor Dennis John Kucinich and Governor and Lieutenant Democratic All Precincts Tara L. Samples Governor Bill O’Neill and Chantelle C. Governor and Lieutenant Democratic All Precincts Lewis Governor Paul E. Ray and Jerry M. Governor and Lieutenant Democratic All Precincts Schroeder Governor Joe Schiavoni and Stephanie Governor and Lieutenant Democratic All Precincts Dodd Governor Mike DeWine and Jon Governor and Lieutenant Republican All Precincts Husted Governor Mary Taylor and Nathan D. Governor and Lieutenant Republican All Precincts Estruth Governor Constance Gadell-Newton Governor and Lieutenant Green All Precincts and Brett R. Joseph Governor Steve Dettelbach Attorney General Democratic All Precincts Dave Yost Attorney General Republican All Precincts Zack Space Auditor of State Democratic All Precincts Keith Faber Auditor of State Republican All Precincts Kathleen Clyde Secretary of State Democratic All Precincts Frank LaRose Secretary of State Republican All Precincts Rob Ricahrdson Treasurer of State Democratic All Precincts Sandra O’Brien Treasurer of State Republican All Precincts Robert Sprague Treasurer of State Republican All Precincts Paul Curry(write-in) Treasurer of State Green All Precincts U.S. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 153 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 15, 2007 No. 29 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. lic for which it stands, one nation under God, AUTHORIZING THE CLERK TO IN- The Chaplain, the Reverend Daniel P. indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. FORM THE PRESIDENT OF THE Coughlin, offered the following prayer: ELECTION OF THE CLERK God, ever mindful of those who place f their trust in You, You bless our com- Mr. HOYER. Madam Speaker, I offer a privileged resolution (H. Res. 166) and ings and our goings, for You are ‘‘God SWEARING OF CLERK OF THE ask for its immediate consideration. with us’’ and guide every step of the HOUSE AND CHIEF ADMINISTRA- way. TIVE OFFICER The Clerk read the resolution, as fol- Today we ask Your blessing upon lows The SPEAKER. The Chair will now Lorraine Miller and Dan Beard as they H. RES. 166 enter this Chamber to be sworn in as swear in the new officers of the House, Officers of the House of Representa- Lorraine C. Miller as the Clerk of the Resolved, That the Clerk be instructed to tives. May they faithfully fulfill the House, and Daniel P. Beard as the Chief inform the President of the United States Administrative Officer. that the House of Representatives has elect- duties that are about to be laid upon ed Lorraine C. Miller, a citizen of the State them and serve this noble institution The officers presented themselves in of Texas, Clerk of the House of Representa- and its Members with diligence, pru- the well of the House and took the oath tives of the One Hundred Tenth Congress. -

Election 2006

APPENDIX: CANDIDATE PROFILES BY STATE We analyzed the fair trade positions of candidates in each race that the Cook Political Report categorized as in play. In the profiles below, race winners are denoted by a check mark. Winners who are fair traders are highlighted in blue text. Alabama – no competitive races___________________________________________ Alaska_________________________________________________________________ Governor OPEN SEAT – incumbent Frank Murkowski (R) lost in primary and was anti-fair trade. As senator, Murkowski had a 100% anti-fair trade voting record. 9 GOP Sarah Palin’s trade position is unknown. • Democratic challenger Tony Knowles is a fair trader. In 2004, Knowles ran against Lisa Murkowski for Senate and attacked her for voting for NAFTA-style trade deals while in the Senate, and for accepting campaign contributions from companies that off-shore jobs.1 Arizona________________________________________________________________ Senate: Incumbent GOP Sen. Jon Kyl. 9 Kyl is anti-fair trade. Has a 100% anti-fair trade record. • Jim Pederson (D) is a fair trader. Pederson came out attacking Kyl’s bad trade record in closing week of campaign, deciding to make off-shoring the closing issue. On Nov. 3 campaign statement: “Kyl has repeatedly voted for tax breaks for companies that ship jobs overseas, and he has voted against a measure that prohibited outsourcing of work done under federally funded contracts,” said Pederson spokesman Kevin Griffis, who added that Pederson “wants more protections [in trade pacts] related to child labor rules and environmental safeguards to help protect U.S. jobs.”2 House Arizona 1: GOP Rep. Rick Renzi incumbent 9 Renzi is anti-fair trade. 100% bad trade vote record. -

Intraparty in the US Congress.Pages

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2cd17764 Author Bloch Rubin, Ruth Frances Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ! ! ! ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! by! Ruth Frances !Bloch Rubin ! ! A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley ! Committee in charge: Professor Eric Schickler, Chair Professor Paul Pierson Professor Robert Van Houweling Professor Sean Farhang ! ! Fall 2014 ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! Copyright 2014 by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abstract ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Eric Schickler, Chair The purpose of this dissertation is to supply a simple and synthetic theory to help us to understand the development and value of organized intraparty blocs. I will argue that lawmakers rely on these intraparty organizations to resolve several serious collective action and coordination problems that otherwise make it difficult for rank-and-file party members to successfully challenge their congressional leaders for control of policy outcomes. In the empirical chapters of this dissertation, I will show that intraparty organizations empower dissident lawmakers to resolve their collective action and coordination challenges by providing selective incentives to cooperative members, transforming public good policies into excludable accomplishments, and instituting rules and procedures to promote group decision-making. -

Bloch Rubin ! ! a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of The

! ! ! ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! by! Ruth Frances !Bloch Rubin ! ! A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley ! Committee in charge: Professor Eric Schickler, Chair Professor Paul Pierson Professor Robert Van Houweling Professor Sean Farhang ! ! Fall 2014 ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! Copyright 2014 by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abstract ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Eric Schickler, Chair The purpose of this dissertation is to supply a simple and synthetic theory to help us to understand the development and value of organized intraparty blocs. I will argue that lawmakers rely on these intraparty organizations to resolve several serious collective action and coordination problems that otherwise make it difficult for rank-and-file party members to successfully challenge their congressional leaders for control of policy outcomes. In the empirical chapters of this dissertation, I will show that intraparty organizations empower dissident lawmakers to resolve their collective action and coordination challenges by providing selective incentives to cooperative members, transforming public good policies into excludable accomplishments, and instituting rules and procedures to promote group decision-making. And, in tracing the development of intraparty organization through several well-known examples of party infighting, I will demonstrate that intraparty organizations have played pivotal — yet largely unrecognized — roles in critical legislative battles, including turn-of-the-century economic struggles, midcentury battles over civil rights legislation, and contemporary debates over national health care policy. -

Lisa-Marie Grønning

Lisa-Marie Grønning Campaign Finance and the effects of the Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission Master’s thesis in Political Science Trondheim, May 2013 Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) Faculty of Social Sciences and Technology Management, Department of Sociology and Political Science. I II Abstract In the 2010 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, the Court held that political speech of corporations is entitled to the same rights as political speech by individuals. They ruled that restrictions on independent expenditures by corporations and labor unions are unconstitutional on Frist Amendment grounds. In this thesis I test two hypotheses. First that outside spending in the 2012 Presidential election was abnormally high because of Citizens United and second, that the increase in outside spending benefited the Republican Party in the 2012 Ohio House elections. I find that Citizens United is the reason for the increase in spending by outside groups, and that this benefited the Republican Part in the 2012 Ohio House elections. III IV Acknowledgement I would like to dedicate this Master thesis to my mother, as she has always encouraged me to pursue this Master’s Degree. During my time as a student I have many times doubted myself. It was your strong desire to see me succeed that kept me going, and that made giving up way harder than trying. As I type up this acknowledgement I am realizing that I have finally accomplished a goal I had set for myself years ago. During my time here at NTNU, I can honestly say that I have pushed myself to the limit in order reach this goal. -

Congressional Delegation

CONGRESSIONAL DELEGATION Boise Depot Tower Photo courtesy of: Boise Convention & Visitors Bureau CONGRESSIONAL DELEGATION 39 Congressional Districts 40 IDAHO BLUE BOOK Congressional Qualifi cations Method of Offi cer Selection Qualifi cation Term of Offi ce United Elected by greatest 30 years of age, US Six years States number of votes in citizen for at least 9 Senator general election years and an Idaho resident United Elected by greatest 25 years of age, US Two years States number of votes in citizen for at least 7 Congressman general election years and an Idaho resident Article I of the U.S. Constitution states that Congress will consist of two separate houses. A lawmaking body with two houses is called a bicameral legislature. The two houses that make up the U.S. Congress are the House of Representatives and the Senate. Congress is the primary lawmaking body in the U.S. government. To solve problems, Members of Congress introduce legislative proposals called bills or resolutions. After considering these proposals, Members vote to adopt or to reject them. Members of Congress also review the work of executive agencies to determine if they are following government policy, and may introduce new legislation based on what they discover. Bills accepted by both houses of Congress and by the President become law. When the President vetoes a bill and returns it to Congress, Congress reviews the reasons for the rejection but may still act to pass the bill. The U.S. Constitution allows Congress to override the President’s veto with a two-thirds majority vote of both the House and the Senate.