RQ Interview Dr. Roger Nicole: a Living Legacy Interview by John R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTEGRITY a Lournøl of Christiøn Thought

INTEGRITY A lournøl of Christiøn Thought PLTBLISHED BY THE COMMISSION FOR THEOLOGICAL INTEGRITY OF THE NAIIONALASSOCIATION OF FREE WILLBAPTISTS Editor Paul V. Harrison Pastoq Cross Timbers Free Will Baptist Church Assistønt Editor Robert E. Picirilli Professor Emeritus, Free Will Baptist Bible College Editorøl Board Tim Eatoru Vice-President, Hillsdale Free Will Baptist College Daryl W Ellis, Pastor, Butterfield Free Wilt Baptist Church, Aurora, Illinois Keith Fletcheq Editor-in-Chief Randall House Publications F. Leroy Forlines, Professor Emeritus, Free Will Baptist Bible College Jeff Manning, Pastor, Unity Free Will Baptist Church, Greenville, North Carolina Garnett Reid, Professo¡, Free Will Baptist Bible College Integrity: A Journøl of Chrístian Thought is published in cooperation with Randall House Publications, Free Will Baptist Bible College, and Hillsdale Free Will Baptist College. It is partially funded by those institutions and a number of interested churches and individuals. Integrity exists to stimulate and provide a forum for Christian scholarship among Free Will Baptists and to fulfill the purposes of the Commission for Theological Integrity. The Commission for Theological Integrity consists of the following members: F. Leroy Forlines (chairman), Dãryl W. Ellis, Paul V. Harisory Jeff Manning, and J. Matthew Pinson. Manuscripts for publication and communications on editorial matters should be directed to the attention of the editor at the following address: 866 Highland Crest Drive, Nashville, Tennessee 37205. E-rnall inquiries should be addressed to: [email protected]. Additional copies of the journal can be requested for $6.00 (cost includes shipping). Typeset by Henrietta Brozon Printed by Randøll House Publications, Nashaille, Tennessee 37217 OCopyright 2003 by the Comrnission for Theological Integrity, National Association of Free Will Baptists Printed in the United States of America Contents Introduction .......7-9 PAULV. -

2009-10 Academic Catalog

catalog 2009/10 admissions office 800.600.1212 [email protected] www.gordonconwell.edu/charlotte/admissions 14542 Choate Circle, Charlotte, NC 28273 704.527.9909 ~ www.gordonconwell.edu Contents CATALOG 2009/10 GORDON-CONWELL THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY–CHARLOTTE 1 Introduction 37 Degree Programs 3 History and Accreditation 40 Master of Divinity 4 President’s Message 41 Master of Arts 6 Our Vision and Mission 43 Master of Arts in Religion 8 Statement of Faith 43 Doctor of Ministry 10 Community Life Statement 46 Checksheets 11 Faculty 58 Seminary Resources 25 Board of Trustees 59 The Harold John Ockenga Institute 25 Emeriti 59 Semlink 64 Campus Ethos and Resources 26 Admissions 69 Associated Study Opportunities 28 Tuition Charges 29 Financial Assistance 71 Course Descriptions 35 Other Campuses 72 Division of Biblical Studies 77 Division of Christian Thought 80 Division of the Ministry of the Church 85 Calendar 2009-2010 2 introduction history Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary has a rich heritage, spanning more than a century. The school’s roots are found in two institutions which have long provided evangelical leadership for the Christian church in a variety of ministries. The Conwell School of Theology was founded in Philadelphia in 1884 by the Rev. Russell Conwell, a prominent Baptist minister. In 1889, out of a desire to equip “men and women in practical religious work... and to furnish them with a thoroughly biblical training,” the Boston Missionary Training School was founded by another prominent Baptist minister, the Rev. Adoniram J. Gordon. The Conwell School of Theology and Gordon Divinity School merged in 1969 through the efforts of philanthropist J. -

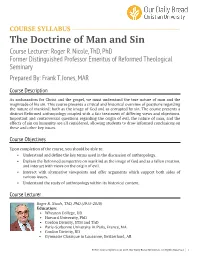

The Doctrine of Man and Sin Course Lecturer: Roger R

COURSE SYLLABUS The Doctrine of Man and Sin Course Lecturer: Roger R. Nicole, ThD, PhD Former Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Reformed Theological Seminary Prepared By: Frank T. Jones, MAR Course Description As ambassadors for Christ and the gospel, we must understand the true nature of man and the magnitude of his sin. This course presents a critical and historical overview of positions regarding the nature of mankind: both as the image of God and as corrupted by sin. The course presents a distinct Reformed anthropology coupled with a fair treatment of differing views and objections. Important and controversial questions regarding the origin of evil, the nature of man, and the effects of sin on humanity are all considered, allowing students to draw informed conclusions on these and other key issues. Course Objectives Upon completion of the course, you should be able to: • Understand and define the key terms used in the discussion of anthropology. • Explain the Reformed perspective on mankind as the image of God and as a fallen creation, and interact with views on the origin of evil. • Interact with alternative viewpoints and offer arguments which support both sides of various issues. • Understand the study of anthropology within its historical context. Course Lecturer Roger R. Nicole, ThD, PhD (1915-2010) Education: • Wheaton College, DD • Harvard University, PhD • Gordon Divinity, STM and ThD • Paris-Sorbonne University in Paris, France, MA • Gordon Divinity, BD • Gymnasie Classique in Lausanne, Switzerland, AB ST504 Course Syllabus -

EVANGELICAL DICTIONARY of THEOLOGY

EVANGELICAL DICTIONARY of THEOLOGY THIRD EDITION Edited by DANIEL J. TREIER and WALTER A. ELWELL K Daniel J. Treier and Walter A. Elwell, eds., Evangelical Dictionary of Theology Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 1984, 2001, 2017. Used by permission. _Treier_EvangelicalDicTheo_book.indb 3 8/17/17 2:57 PM 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, 3rd edition General Editors: Daniel J. Treier and Walter A. Elwell Advisory Editors: D. Jeffrey Bingham, Cheryl Bridges Johns, John G. Stackhouse Jr., Tite Tiénou, and Kevin J. Vanhoozer © 1984, 2001, 2017 by Baker Publishing Group Published by Baker Academic a division of Baker Publishing Group P.O. Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516–6287 www.bakeracademic.com Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Treier, Daniel J., 1972– editor. | Elwell, Walter A., editor. Title: Evangelical dictionary of theology / edited by Daniel J. Treier, Walter A. Elwell. Description: Third edition. | Grand Rapids, MI : Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2017. Identifiers: LCCN 2017027228 | ISBN 9780801039461 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Theology—Dictionaries. Classification: LCC BR95 .E87 2017 | DDC 230/.0462403—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017027228 Unless otherwise labeled, Scripture quotations are from the Holy Bible, New International Version®. -

Table of Contents Preface

Table of Contents Preface A Tribute to Roger Nicole - Timothy George General Introduction - Frank A. James III Abbreviations Part I: Atonement in the Old and New Testaments - Charles E. Hill 1. Atonement in the Pentateuch - Emile Nicole 2. Atonement in Psalm 51 - Bruce K. Waltke 3. Atonement in Isaiah 53 - J. Alan Groves 4. Atonement in the Synoptic Gospels and Acts - Royce Gordon Gruenler 5. Atonement in John's Gospel and Epistles - J. Ramsey Michaels 6. Atonement in Romans 3:21-26 - D. A. Carson 7. Atonement in the Pauline Corpus - Richard Gaffin 8. Atonement in Hebrews - Simon J. Kistemaker 9. Atonement in James, Peter and Jude - Dan G. McCartney 10. Atonement in the Apocalypse of John - Charles E. Hill Part II: The Atonement in Church History - Frank A. James III 11. Interpreting Atonement in Augustine's Preaching - Stanley P. Rosenberg 12. The Atonement in Medieval Theology - Gwenfair M. Walters 13. The Atonement in Martin Luther's Theology - Timothy George 14. The Atonement in John Calvin's Theology - Henri Blocher 15. Definite Atonement in Historical Perspective - Raymond A. Blacketer 16. The Atonement in Herman Bavinck's Theology - Joel R. Beeke 17. The Ontological Presuppositions of Barth's Doctrine of the Atonement - Bruce L. McCor- mack 18. The Atonement in Postmodernity: Guilt, Goats and Gifts - Kevin J. Vanhoozer Part III: The Atonement in the Life of the Christian and the Church - Frank A. James III 19. The Atonement in the Life of the Christian - J. I. Packer 20. Preaching the Atonement - Sinclair B. Ferguson Postscript on Penal Substitution - Roger Nicole Select Bibliography List of Contributors Subject Index Scripture Index GloryofAtonement.book Page 7 Friday, February 13, 2004 2:59 PM PREFACE Academics are prone to lamentation—it is an occupational hazard. -

Southwestern Journal of Theology Scripture, Culture, and Missions

Journal of Theology and missions Southwestern Scripture, Culture, Scripture, Culture, SWJT Scripture, Culture, and Missions Vol. 55 No. 1 • Fall 2012 SCRIPTURE, CULTURE, AND MISSIONS Southwestern Journal of Theology Volume 55 Fall 2012 Number 1 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Paige Patterson, President, Professor of Theology, and L.R. Scarborough Chair of Evangelism (“Chair of Fire”) MANAGING EDITOR Terry L. Wilder, Professor and Wesley Harrison Chair of New Testament EDITORIAL BOARD Jason G. Duesing, Vice President for Strategic Initiatives and Assistant Professor of Historical Theology Keith E. Eitel, Professor of Missions, Dean of the Roy Fish School of Evangelism and Missions, and Director of the World Missions Center Mark A. Howell, Senior Pastor, First Baptist Church Daytona Beach Evan Lenow, Assistant Professor of Ethics and Director of the Riley Center Miles S. Mullin II, Assistant Professor of Church History, J. Dalton Havard School for Theological Studies Steven W. Smith, Professor of Communication, Dean of the College at Southwestern Jerry Vines, Jerry Vines Ministries Joshua E. Williams, Assistant Professor of Old Testament BOOK REVIEW EDITOR AND EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Ched Spellman Southwestern Journal of Theology invites English-language submissions of original research in biblical studies, historical theology, systematic theology, ethics, philosophy of religion, homiletics, pastoral ministry, evangelism, missiology, and related fields. Articles submitted for consideration should be neither published nor under review for publication elsewhere. The recommended length of articles is between 4000 and 8000 words. For information on editorial and stylistic requirements, please contact the journal’s Editorial Assistant at journal@ swbts.edu. Articles should be sent to the Managing Editor, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, P.O. -

Evangelism and Social Concern in the Theology of Carl F. H. Henry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary EVANGELISM AND SOCIAL CONCERN IN THE THEOLOGY OF CARL F. H. HENRY A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Of Doctor of Philosophy By Jerry M. Ireland July 27, 2014 Copyright 2014 Jerry M. Ireland All Rights Reserved ii To Paula and Charis, through whom I experience the love of God in the most profound ways. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................ X ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................... XI CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1 RESEARCH QUESTION ...................................................................................................... 4 Relevance of This Study ............................................................................................. 7 METHODOLOGY AND CHAPTER SUMMARIES .................................................................. 10 Potential Bias ............................................................................................................ 11 Nature of the -

Past Presidents and Past Conferences

PAST PRESIDENTS 1949 Clarence Bouma 1972 Robert L. Saucy 1995 George W. Knight, III Calvin Theological Seminary Talbot Seminary Knox Theological Seminary 1950 Clarence Bouma 1973 Arthur H. Lewis 1996 Robert C. Newman Calvin Theological Seminary Bethel College Biblical Theological Seminary 1951 Merrill Tenney 1974 Richard Longenecker 1997 Moisés Silva Wheaton College Wycliffe College Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary 1952 Charles Woodbridge 1975 Bruce K. Waltke Fuller Theological Seminary Dallas Theological Seminary 1998 Norman L. Geisler Southern Evangelical Seminary 1953 Frank Neuberg 1976 Simon J. Kistemaker Wheaton College Reformed Theological Seminary 1999 Wayne A. Grudem Trinity Evangelical Divinity School 1954 John Walvoord 1977 Walter C. Kaiser Jr. Dallas Theological Seminary Trinity Evangelical Divinity School 2000 John H. Sailhamer Southeastern Baptist Theological 1955 Harold Kuhn 1978 Stanley N. Gundry Seminary Asbury Theological Seminary Moody Bible Institute 2001 Darrell L. Bock 1956 Roger Nicole 1979 Marten H. Woudstra Dallas Theological Seminary Gordon Divinity School Calvin Theological Seminary 2002 Millard J. Erickson 1957 Ned Stonehouse 1980 Wilber B. Wallis George W. Truett Theological Westminster Seminary Covenant Theological Seminary Seminary, Baylor University 1958 Warren Young 1981 Kenneth L. Barker 2003 David M. Howard Jr. Northern Baptist Seminary Dallas Theological Seminary Bethel Theological Seminary 1959 Gilbert Johnson 1982 Alan F. Johnson 2004 Gregory K. Beale Nyack Missionary College Wheaton College Wheaton College 1960 Allan MacRae 1983 Louis Goldberg 2005 Craig A. Blaising Faith Seminary Moody Bible Institute Southwestern Baptist Theological 1961 Laird Harris 1984 W. Haddon Robinson Seminary Covenant Seminary Denver Seminary 2006 Edwin M. Yamauchi 1962 Ralph Earle 1985 Richard V. Pierard Miami University of Ohio Nazarene Seminary Indiana State University 2007 Francis Beckwith (resigned) 1963 Vernon Grounds 1986 Gleason L. -

Download Entire Program

i:WAN c E~.I~m~'trfrffire:o~[~A!J I ·e .":7ifll-I I:) !J( ~ ' / - KT il'~ A LEifER FROM "fH E PRESJ DEN"r-HECT De~r ETS member: Welcome to the ETS National Meeting for 2005 at Valley Forge. Our theme, "Christianity in the Early Centuries," was chosen by the Executive Committee in view of sev eral current developments. First the phenomenal sale (25 million plus copies) of Dan Brown's novel, The Da Vinci Code, has aroused great public interest in the possibility th<Jt the (Catholic) Church has engaged in a conspiracy to conceal the "fact" that Jesus was mM ried to Mary Magadalene, who Brown e1lleges was portrayed in Da Vinci's painting of The Last Supper. Second, Brown claims that his thesis is IJased in p~rt on the Gnostic Gospels, discovered at Nag Hammadi in Egypt in 1945. While Brown's mystery novel may be easily dismissed as fictional fantasy, important scholars such as Elaine Pagels, Karen King, and Bart Ehrman have written popular expositions which challenge the accepted canon of New Testament documents, and the Eusebian narrative of orthodoxy and competing heterodoxies. They are also articulate spokespersons, who make a persuasive case on television, reaching a vast audience. Protestants in general, and evangelicals in particular have been criticized-with some justification-for leapfrogging from the New Testament er,1 to the Reformation, neglecting with disdain the intervening centuries. We are fortunate that we have four eminent church historians-Christopher Hall, Nicholas Perrin, Jeffrey Bingham, and Paul Trebilco-who will address these issues in their plenary addresses. -

Haddington House Journal 2007 Introductions Or Surveys

Book Reviews 85 Book Reviews The Kregel Bible Atlas. Tim Dowley. A worldwide coedition by Angus Hudson Ltd., London. Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2003, 96 pp., hc. ISBN 0-8254-2467-4 At last an affordable, accurate and readable atlas with super photographs and maps for Christians to gain tremendous insight into the Scriptures! I was introduced by a student to this fine, little atlas as a valuable resource for colleges in the developing world. It is suitable for the whole world, and I encourage readers in any country to consider this excellent publication. The book is divided into four parts: ―The Lands of the Bible‖, ―The Old Testament‖, ―Between the Testaments‖ and ―The New Testament‖. I am convinced many Bible colleges in the developing world can use this for several courses, such as Old Testament and New Testament 86 Haddington House Journal 2007 introductions or surveys. I tested it out for a New Testament Introduction class in Africa and found it very helpful. Few atlases can combine three things well: written commentary, good pictures and illustrations, and high quality maps. The Kregel Bible Atlas manages to do all three, no doubt due to the writer and compiler‘s knowledge and abilities. Tim Dowley has traveled extensively in Turkey, Israel and the Bible lands; and this book clearly reflects a seasoned and knowledgeable writer. He is also the editor of the noted Baker Atlas of Christian History, not to mention several other resources, and he appears to have a good understanding of the visual cultural age in which we live. Yet this is not just a carefully crafted visual work, but in addition the written commentary is so highly informative that it helps open up much of the Scripture. -

A Comparative Investigation of the Concept of Nature in the Writings of Henry M. Morris and Bernard L. Ramm

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2006 A Comparative Investigation of the Concept of Nature in the Writings of Henry M. Morris and Bernard L. Ramm Andrew M. Mutero Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mutero, Andrew M., "A Comparative Investigation of the Concept of Nature in the Writings of Henry M. Morris and Bernard L. Ramm" (2006). Dissertations. 104. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/104 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary A COMPARATIVE INVESTIGATION OF THE CONCEPT OF NATURE IN THE WRITINGS OF HENRY M. MORRIS AND BERNARD L. RAMM A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Andrew M. Mutero February 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3238259 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

ST505: the Doctrine of Salvation Course Lecturer: Roger R

COURSE SYLLABUS ST505: The Doctrine of Salvation Course Lecturer: Roger R. Nicole, ThD, PhD Former Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Reformed Theological Seminary Prepared By: Frank T. Jones, MAR About This Course This course was originally created through the Institute of Theological Studies in association with the Evangelical Seminary Deans’ Council. There are nearly 100 evangelical seminaries of various denominations represented within the council and many continue to use the ITS courses to supplement their curriculum. The lecturers were selected primarily by the Deans’ Council as highly recognized scholars in their particular fields of study. Course Description “Sirs, what must I do to be saved?” No question is more important or more debated than this one posed by the Philippian jailer. This course presents a critical and historical overview of the message, plan, and components of salvation. The lectures trace each element of the salvation process, from God’s decree to our final glorification and union with Christ. Topics such as the order of salvation, the nature of justification, and the possibility of perfection are given in-depth treatment. The course emphasizes a Reformed view of salvation, while offering fair treatment to all sides. Course Objectives Upon completion of the course, you should be able to: • Understand and define the key terms used in the discussion of soteriology. • Explain the Reformed perspective on this process as it relates to our predestination, justification, sanctification, and glorification. • Interact with alternative viewpoints and offer arguments which support both sides of various issues. • Understand the study of soteriology within its historical context. ST505 Course Syllabus | © 2015 Christian University GlobalNet/Our Daily Bread Ministries.