In Response to the Compromise of 1850 Lincoln's Speech On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compromise of 1850 Earlier You Read About the Missouri Compromise and the Wilmot Proviso

Compromise of 1850 Earlier you read about the Missouri Compromise and the Wilmot Proviso. Keep them in mind as you read here What is a compromise? A compromise is a resolution of a problem in which each side gives up demands or makes concession. Earlier you read about the Missouri Compromise. What conflict did it resolve? It kept the number of slave and free states equal by admitting Maine as free and Missouri as slave and it provided for a policy with respect to slavery in the Louisiana Territory. Other than in Missouri, the Compromise prohibited slavery north of 36°30' N latitude in the land acquired in the Louisiana Purchase. Look at the 1850 map. Notice how the "Missouri Compromise Line" ends at the border to Mexican Territory. In 1850 the United States controls the 36°30' N latitude to the Pacific Ocean. Will the United States allow slavery in its new territory? Slavery's Expansion Look again at this map and watch for the 36°30' N latitude Missouri Compromise line as well as the proportion of free and slave states up to the Civil War, which begins in 1861. WSBCTC 1 This map was created by User: Kenmayer and is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license (CC-BY 3.0) [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:US_Slave_Free_1789-1861.gif]. Here's a chart that compares the Missouri Compromise with the Compromise of 1850. WSBCTC 2 Wilmot Proviso During the Mexican-American War in 1846, David Wilmot, a Democratic congressman from Pennsylvania, proposed in an amendment to a military appropriations bill that slavery be banned in all the territories acquired from Mexico. -

The Wilmot Proviso the Wilmot Proviso Was a Rider (Or Provision) Attached to an Appropriations Bill During the Mexican War

The Wilmot Proviso The Wilmot Proviso was a rider (or provision) attached to an appropriations bill during the Mexican War. It stated that slavery would be banned in any territory won from Mexico as a result of the war. While it was approved by the U.S. House of Representatives (where northern states had an advantage due to population), it failed to be considered by the U.S. Senate (where slave and free states were evenly divided). Though never enacted, the Wilmot Proviso signaled significant challenges regarding what to do with the extension of slavery into the territories. The controversy over slavery’s extension polarized public opinion and resulted in dramatically increased sectional tension during the 1850s. The Wilmot Proviso was introduced by David Wilmot from Pennsylvania and mirrored the wording of the Northwest Ordinance on slavery. The proviso stated “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory” that might be gained from Mexico as a result of the Mexican-American War. The issue of the extension of slavery was not new. As northern states abolished the institution of slavery, they pushed to keep the practice from extending into new territory. The push for abolition began before the ratification of the Constitution with the enactment of the Northwest Ordinance which outlawed slavery in the Northwest Territory. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 brought a large amount of new land into the U.S. that, over time, would qualify for territorial status and eventually statehood. The proviso stated “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory” that might be gained from Mexico as a result of the Mexican-American War. -

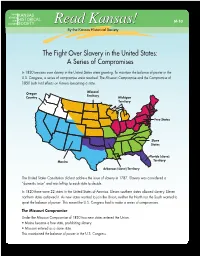

Read Kansas! Read Kansas!

YOUR KANSAS STORIES HISTORICAL OUR M-10 HISTORY SOCIETY Read Kansas! By the Kansas Historical Society The Fight Over Slavery in the United States: A Series of Compromises In 1820 tensions over slavery in the United States were growing. To maintain the balance of power in the U.S. Congress, a series of compromise were reached. The Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850 both had effects on Kansas becoming a state. Missouri Oregon Territory Country Michigan Territory Free States Slave States Florida (slave) Mexico Territory Arkansas (slave) Territory The United States Constitution did not address the issue of slavery in 1787. Slavery was considered a “domestic issue” and was left up to each state to decide. In 1820 there were 22 states in the United States of America. Eleven southern states allowed slavery. Eleven northern states outlawed it. As new states wanted to join the Union, neither the North nor the South wanted to upset the balance of power. This meant the U.S. Congress had to make a series of compromises. The Missouri Compromise Under the Missouri Compromise of 1820 two new states entered the Union. • Maine became a free state, prohibiting slavery. • Missouri entered as a slave state. This maintained the balance of power in the U.S. Congress. The Missouri Compromise did something else that made it important. • For the first time the federalgovernment, rather than the states, decided on the issue of slavery. • The compromise banned slavery in the northern portion of the Louisianam Territory. This included the land that was to become Kansas. The Compromise of 1850 The Compromise of 1850 was a series of bills that passed the U.S. -

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850: the Tipping Point

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850: The Tipping Point During the Antebellum period, tensions between the Northern and Southern regions of the United States escalated due to debates over slavery and states’ rights. These disagreements between the North and South set the stage for the Civil War in 1861. Following the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, the United States acquired 500,000 square miles of land from Mexico and the question of whether slavery would be allowed in the territory was debated between the North and South. As a solution, Congress ultimately passed the The Compromise of 1850. The Compromise resulted in California joining the Union as a free state and slavery in the territories of New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona and Utah, to be determined by popular sovereignty. In order to placate the Southern States, the Fugitive Slave Act was put into place to appease the Southerners and to prevent secession. This legislation allowed the federal government to deputize Northerners to capture and return escaped slaves to their owners in the South. Although the Fugitive Slave Act was well intentioned, the plan ultimately backfired. The Fugitive Slave Act fueled the Abolitionist Movement in the North and this angered the South. The enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act increased the polarization of the North and South and served as a catalyst to events which led to the outbreak of the Civil War. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 brought into sharp focus old differences between the North and South and empowered the Anti-Slavery movement. Prior to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the Act of 1793 was passed and this allowed for slave owners to enter free states to capture escaped slaves. -

Slavery and the Civil War

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Slavery and the Civil War www.nps.gov The role of slavery in bringing on the Civil War has been hotly debated for decades. One important way of approaching the issue is to look at what contemporary observers had to say. In March 1861, Alexander Stephens, vice president of the Confederate States of America, gave his view: The new [Confederate] constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution — African slavery as it exists amongst us — the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution . The prevailing ideas entertained by . most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old constitution, were that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically . Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error . Alexander H. Stephens, vice Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its president of the Confederate corner–stone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that States of America. slavery — subordination to the superior race — is his natural and normal condition. — Alexander H. Stephens, March 21, 1861, reported in the Savannah Republican, emphasis in the original. Today, most professional historians agree with Stephens that could not be ignored. -

John C. Fremont and the Violent Election of 1856

Civil War Book Review Fall 2017 Article 9 Lincoln's Pathfinder: John C. rF emont And The Violent Election Of 1856 Stephen D. Engle Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Engle, Stephen D. (2017) "Lincoln's Pathfinder: John C. rF emont And The Violent Election Of 1856," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 19 : Iss. 4 . DOI: 10.31390/cwbr.19.4.14 Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol19/iss4/9 Engle: Lincoln's Pathfinder: John C. Fremont And The Violent Election Of Review Engle, Stephen D. Fall 2017 Bicknell, John Lincoln’s Pathfinder: John C. Fremont and the Violent Election of 1856. Chicago Review Press, $26.99 ISBN 1613737971 1856: Moment of Change The famed historian David Potter once wrote that if John Calhoun had been alive to witness the election of 1856, he might have observed “a further snapping of the cords of the Union.” “The Whig cord had snapped between 1852 and 1856,” he argued “and the Democratic cord was drawn very taut by the sectional distortion of the party’s geographical equilibrium.” According to Potter, the Republican party “claimed to be the only one that asserted national principles, but it was totally sectional in its constituency, with no pretense to bi-sectionalism, and it could not be regarded as a cord of the Union at all.”1 He was right on all accounts, and John Bicknell captures the essence of this dramatic political contest that epitomized the struggle of a nation divided over slavery. To be sure, the election of 1856 marked a turning point in the republic’s political culture, if for no other reason than it signaled significant change on the democratic horizon. -

The Compromise of 1850

IN, p. 20R The Compromise of 1850 The Missouri Compromise maintained an uneasy peace between the North and the South for several decades. Then, in 1850, the issue of slavery and its expansion surfaced once more. The discovery of gold at a sawmill in California in 1848 led to the Gold Rush of 1849, which resulted in California's population increasing more than tenfold in a few years. This led to Californians applying for admission to the Union as a free state in 1849 and a resumption of the slavery-expansion controversy. The issue was even more complicated because of the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican War in 1848. By its terms, Mexico relinquished claims to Texas above the Rio Grande River and ceded New Mexico and Upper California to the United States. This vast territory was organized into Utah Territory in the North and New Mexico Territory in the South. (In time, the states of Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico would be formed from the region, as well as parts of Colorado and Wyoming.) The burning question was: Would these new territories be free or slave? Would another compromise be worked out that would once again avert war? The North hammered away at the evils of slavery, while the South, if it did not have its way, threatened to secede from the Union. With storm clouds on the horizon, the future looked bleak. Once again, the Great Compromiser, Henry Clay, came to the rescue. In 1850, he was over 70 years old and in failing health. -

FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW of 1850 Wikimedia Commons Wikimedia

THE FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW OF 1850 Wikimedia Commons Wikimedia Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky introducing the Compromise of 1850 in the United States Senate. In 1850, Southerners succeeded in getting a new federal law South to guide about 70 slaves to freedom. “I was free, passed to return fugitive slaves who had escaped to the North. and they should be free,” she said. The U.S. government enforced this law, but some Northern Abolitionists argued that once slaves touched states passed laws to resist it. Sometimes, free blacks and sym- pathetic whites joined to rescue captured fugitive slaves. the soil of a non-slave state, they were free. Some Northern states prohibited county sheriffs from as- The idea of returning fugitive slaves to their own- sisting slave hunters or allowing county jails to hold ers originated at the Constitutional Convention in their captives. 1787. At that time, the Constitution stated: In 1842, the U.S. Supreme Court in Prigg v. No Person held to Service or Labor in one State, Pennsylvania found the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, constitutional. However, enforcement of the law was shall, in Consequence of any Law of Regulation the responsibility of the federal government, held the therein, be discharged from such Service or Labor, court, not the states. The Supreme Court also decided but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to that slave holders had “the complete right and title of whom such Service or Labor may be due. (U.S. ownership in their slaves, as property, in every state Const. -

Westward Expansion and the Mexican-American War by Bianca Wilson

Westward Expansion and the Mexican-American War Duration 4 90-minute block periods Class/Grade Level Advanced Placement English Language & Composition/ 11th grade Number of Students 20 students Location Classroom (days 1,3 and 4) and Computer Lab (day 2) Key Vocabulary Transcendentalism- a movement in nineteenth-century American literature and thought, calling on people to trust their individual intuition. Transcendentalism is most often associated with Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Annex to attach, append, or add, especially to something larger or more important Manifest Destiny- the belief that the United States was destined to expand beyond its present territorial boundaries Missouri Compromise of 1820- In the years leading up to the Missouri Compromise of 1820, tensions began to rise between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions within the U.S. Congress and across the country. They reached a boiling point after Missouri’s 1819 request for admission to the Union as a slave state, which threatened to upset the delicate balance between slave states and free states. To keep the peace, Congress orchestrated a two-part compromise, granting Missouri’s request but also admitting Maine as a free state. It also passed an amendment that drew an imaginary line across the former Louisiana Territory, establishing a boundary between free and slave regions that remained the law of the land until it was negated by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Compromise of 1850- Divisions over slavery in territory gained in the Mexican-American War (1846-48) were resolved in the Compromise of 1850. It consisted of laws admitting California as a free state, creating Utah and New Mexico territories with the question of slavery in each to be determined by popular sovereignty, settling a Texas-New Mexico boundary dispute in the former's favor, ending the slave trade in Washington, D.C., and making it easier for southerners to recover fugitive slaves. -

A Nation Divided- 2021 W

A Nation Divided Binder Page 85 Name ______________________________________________________ Per ______________ “A Nation Divided” Date ___________________ A Nation Divided- The Coming of the Civil War “’A house divided against itself cannot stand.’ I believe this government cannot endure permanently, half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall— but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all of one thing or all the other.” … Abraham Lincoln 1858 I. The Missouri Compromise (1820) Devised by Henry Clay in order to keep the number of free and slave states equal. It had three parts: A. Missouri would be admitted as a slave state. B. Maine would be broken off from Massachusetts and admitted as a free state to keep the balance in the Senate. C. A line would be drawn through the Louisiana Purchase. North of that line, slavery would not be allowed. South of that line, it would be. The main reason that this compromise was only a temporary solution was because: Manifest Destiny. New land would be added that wasn’t part of the United States when the Missouri Compromise was passed. A Nation Divided II. The Compromise of 1850. In the year 1850, California requested to enter the Union as a free state, and for the first time the Missouri Compromise of 1820 did not help to keep the states balanced. Henry Clay came up with a more complicated compromise this time. It had four parts. For the 1. California would be 2. -

Causes of Civil War and War

Causes of Civil war and war 1 The Louisiana Purchase (1803) was a foreign policy 6 During the first 100 years of its history, the success· for the United States primarily because it United States followed a foreign policy of (1) secured full control of Florida from Spain (1) forming military defense alliances with European (2) ended French control of the Mississippi River nations (3) ended British occupation of forts on American soil (2) establishing overseas spheres of influence (4) eliminated Russian influence in North America (3) remaining neutral from political connections with other nations 2 The principle of popular sovereignty was an important part of the (4) providing leadership in international organizations 7 Which event was the immediate cause of the secession (1) Indian Removal Act of several Southern states from the Union in 1860? (2) Kansas-Nebraska Act (3) Homestead Act (1) the Dred Scott decision, which declared that all (4) Dawes Act prior compromises on the extension of slavery into the territories were unconstitutional 3 Which event most directly contributed to the growth of (2) the Missouri Compromise, which kept an even New York City as the nation's leading trade center? balance between the number of free and slave (1) use of steamboats on the Mississippi River states (2) opening of the Erie Canal (3) the raid on the Federal arsenal at Harper's Ferry, (3) construction of the National Road which was led by the militant abolitionist John (4) passage of the Pacific Railway Act Brown (4) the election of President Abraham -

Triumph Or Tragedy?: the Compromise of 1850 Middle/High School

Triumph or Tragedy?: The Compromise of 1850 Middle/High School Date: Time: 1-2 class periods Topic: Triumph or Tragedy? The Compromise of 1850 Standards/Benchmarks: 2.14 Students understand the democratic principles of justice, equality, responsibility, and freedom and apply them to real-life situations. 2.16 Students observe, analyze, and interpret human behaviors, social groupings, and institutions to better understand people and the relationships among individuals and among groups. 2.19 Students recognize and understand the relationship between people and geography and apply their knowledge in real-life situations. 2.20 Students understand, analyze, and interpret historical events, conditions, trends, and issues to develop historical perspectives. Content Objectives: SWBAT: Students will learn how to consider a historical event from multiple perspectives and will use critical thinking analyze how a decision affected different groups of people differently. Students will be able to analyze primary sources and narratives to better understand a historical event. Students will be able to communicate their analysis verbally. Activities: Students will watch a video from NBC News Learn outlining the Compromise of 1850, who was involved, and what each side wanted. In addition to the video, students will be handed a summary sheet that includes context and results of the Compromise. (NOTE: There is an error in this video. Students will be split into groups of 4-5, then each group will receive a persona card. Each card tells the story of an individual living during the time of the Compromise of 1850: an enslaved person, a freedman in Boston, a Northern textile factory owner, a Northern abolitionist, and a slave owner in Maryland.