FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW of 1850 Wikimedia Commons Wikimedia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African American Literature in Transition, 1850–1865

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42748-7 — African American Literature in Transition Edited by Teresa Zackodnik Frontmatter More Information AFRICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE IN TRANSITION, – The period of – consists of violent struggle and crisis as the United States underwent the prodigious transition from slaveholding to ostensibly “free” nation. This volume reframes mid-century African American literature and challenges our current understand- ings of both African American and American literature. It presents a fluid tradition that includes history, science, politics, economics, space and movement, the visual, and the sonic. Black writing was highly conscious of transnational and international politics, textual circulation, and revolutionary imaginaries. Chapters explore how Black literature was being produced and circulated; how and why it marked its relation to other literary and expressive traditions; what geopolitical imaginaries it facilitated through representation; and what technologies, including print, enabled African Americans to pursue such a complex and ongoing aesthetic and political project. is a Professor in the English and Film Studies Department at the University of Alberta, where she teaches critical race theory, African American literature and theory, and historical Black feminisms. Her books include The Mulatta and the Politics of Race (); Press, Platform, Pulpit: Black Feminisms in the Era of Reform (); the six-volume edition African American Feminisms – in the Routledge History of Feminisms series (); and “We Must be Up and Doing”: A Reader in Early African American Feminisms (). She is a member of the UK-based international research network Black Female Intellectuals in the Historical and Contemporary Context, and is completing a book on early Black feminist use of media and its forms. -

1 States Rights, Southern Hypocrisy

States Rights, Southern Hypocrisy, and the Crisis of the Union Paul Finkelman Albany Law School (Draft only, not for Publication or Distribution) On December 20 we marked -- I cannot say celebrated -- the sesquicentennial of South Carolina's secession. By the end of February, 1861 six other states would follow South Carolina into the Confederacy. Most scholars fully understand that secession and the war that followed were rooted in slavery. As Lincoln noted in his second inaugural, as he looked back on four years of horrible war, in 1861 "One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war."1 What Lincoln admitted in 1865, Confederate leaders asserted much earlier. In his famous "Cornerstone Speech," Alexander Stephens, the Confederate vice president, denounced the Northern claims (which he incorrectly also attributed to Thomas Jefferson) that the "enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically." He proudly declared: "Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his 1 Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1865. 1 natural and normal condition. " Stephens argued that it was "insanity" to believe that "that the negro is equal" or that slavery was wrong.2 Stephens only echoed South Carolina's declaration that it was leaving the Union because "A geographical line has been drawn across the Union, and all the States north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery. -

The Tarring and Feathering of Thomas Paul Smith: Common Schools, Revolutionary Memory, and the Crisis of Black Citizenship in Antebellum Boston

The Tarring and Feathering of Thomas Paul Smith: Common Schools, Revolutionary Memory, and the Crisis of Black Citizenship in Antebellum Boston hilary j. moss N 7 May 1851, Thomas Paul Smith, a twenty-four-year- O old black Bostonian, closed the door of his used clothing shop and set out for home. His journey took him from the city’s center to its westerly edge, where tightly packed tene- ments pressed against the banks of the Charles River. As Smith strolled along Second Street, “some half-dozen” men grabbed, bound, and gagged him before he could cry out. They “beat and bruised” him and covered his mouth with a “plaster made of tar and other substances.” Before night’s end, Smith would be bat- tered so severely that, according to one witness, his antagonists must have wanted to kill him. Smith apparently reached the same conclusion. As the hands of the clock neared midnight, he broke free of his captors and sprinted down Second Street shouting “murder!”1 The author appreciates the generous insights of Jacqueline Jones, Jane Kamensky, James Brewer Stewart, Benjamin Irvin, Jeffrey Ferguson, David Wills, Jack Dougherty, Elizabeth Bouvier, J. M. Opal, Lindsay Silver, Emily Straus, Mitch Kachun, Robert Gross, Shane White, her colleagues in the departments of History and Black Studies at Amherst College, and the anonymous reviewers and editors of the NEQ. She is also grateful to Amherst College, Brandeis University, the Spencer Foundation, and the Rose and Irving Crown Family for financial support. 1Commonwealth of Massachusetts vs. Julian McCrea, Benjamin F. Roberts, and William J. -

MILITANT ABOLITIONIST GERRIT SMITH }Udtn-1 M

MILITANT ABOLITIONIST GERRIT SMITH }UDtn-1 M. GORDON·OMELKA Great wealth never precluded men from committing themselves to redressing what they considered moral wrongs within American society. Great wealth allowed men the time and money to devote themselves absolutely to their passionate causes. During America's antebellum period, various social and political concerns attracted wealthy men's attentions; for example, temperance advocates, a popular cause during this era, considered alcohol a sin to be abolished. One outrageous evil, southern slavery, tightly concentrated many men's political attentions, both for and against slavery. and produced some intriguing, radical rhetoric and actions; foremost among these reform movements stood abolitionism, possibly one of the greatest reform movements of this era. Among abolitionists, slavery prompted various modes of action, from moderate, to radical, to militant methods. The moderate approach tended to favor gradualism, which assumed the inevitability of society's progress toward the abolition of slavery. Radical abolitionists regarded slavery as an unmitigated evil to be ended unconditionally, immediately, and without any compensation to slaveholders. Preferring direct, political action to publicize slavery's iniquities, radical abolitionists demanded a personal commitment to the movement as a way to effect abolition of slavery. Some militant abolitionists, however, pushed their personal commitment to the extreme. Perceiving politics as a hopelessly ineffective method to end slavery, this fringe group of abolitionists endorsed violence as the only way to eradicate slavery. 1 One abolitionist, Gerrit Smith, a wealthy landowner, lived in Peterboro, New York. As a young man, he inherited from his father hundreds of thousands of acres, and in the 1830s, Smith reportedly earned between $50,000 and $80,000 annually on speculative leasing investments. -

Chapter I: the Supremacy of Equal Rights

DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY PASADENA, CALIFORNIA 91125 CHAPTER I: THE SUPREMACY OF EQUAL RIGHTS J. Morgan Kousser SOCIAL SCIENCE WORKING PAPER 620 March 1987 ABSTRACT The black and white abolitionist agitation of the school integ ration issue in Massachusetts from 1840 to 1855 gave us the fi rst school integ ration case filed in Ame rica, the fi rst state sup reme cou rt decision re po rted on the issue, and the fi rst state-wide law banning ra cial disc rimination in admission to educational institutions. Wh o favo red and who opposed school integ ration, and what arguments did each side make? We re the types of arguments that they offe re d diffe rent in diffe re nt fo ru ms? We re they diffe rent from 20th centu ry arguments? Wh y did the movement triumph, and why did it take so long to do so? Wh at light does the st ruggle th row on views on ra ce re lations held by membe rs of the antebellum black and white communities, on the cha racte r of the abolitionist movement, and on the development of legal doct rines about ra cial equality? Pe rhaps mo re gene rally, how should histo ri ans go about assessing the weight of diffe rent re asons that policymake rs adduced fo r thei r actions, and how flawed is a legal histo ry that confines itself to st rictly legal mate ri als? How can social scientific theo ry and statistical techniques be profitably applied to politico-legal histo ry? Pa rt of a la rge r project on the histo ry of cou rt cases and state and local provisions on ra cial disc rimination in schools, this pape r int roduces many of the main themes, issues, and methods to be employed in the re st of the book. -

Compromise of 1850 Earlier You Read About the Missouri Compromise and the Wilmot Proviso

Compromise of 1850 Earlier you read about the Missouri Compromise and the Wilmot Proviso. Keep them in mind as you read here What is a compromise? A compromise is a resolution of a problem in which each side gives up demands or makes concession. Earlier you read about the Missouri Compromise. What conflict did it resolve? It kept the number of slave and free states equal by admitting Maine as free and Missouri as slave and it provided for a policy with respect to slavery in the Louisiana Territory. Other than in Missouri, the Compromise prohibited slavery north of 36°30' N latitude in the land acquired in the Louisiana Purchase. Look at the 1850 map. Notice how the "Missouri Compromise Line" ends at the border to Mexican Territory. In 1850 the United States controls the 36°30' N latitude to the Pacific Ocean. Will the United States allow slavery in its new territory? Slavery's Expansion Look again at this map and watch for the 36°30' N latitude Missouri Compromise line as well as the proportion of free and slave states up to the Civil War, which begins in 1861. WSBCTC 1 This map was created by User: Kenmayer and is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license (CC-BY 3.0) [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:US_Slave_Free_1789-1861.gif]. Here's a chart that compares the Missouri Compromise with the Compromise of 1850. WSBCTC 2 Wilmot Proviso During the Mexican-American War in 1846, David Wilmot, a Democratic congressman from Pennsylvania, proposed in an amendment to a military appropriations bill that slavery be banned in all the territories acquired from Mexico. -

Central Valley Joint Fugitive Task Force

EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA CENTRAL VALLEY JOINT FUGITIVE TASK FORCE For Immediate Press Release Contact: Eastern District of California July 1, 2011 Deputy Jason Ferrell (559)487-5559 Tehachapi – U.S. Marshal Albert Najera, of the Eastern District of California, announced today that the U.S. Marshals Central Valley Joint Fugitive Task Force (CVJFTF) arrested Mitchell Dennis Knox. On June 30, 2011, the Joint Support Operations Center (JSOC), in ATF Headquarters, received information about the possible whereabouts of Mitchell Knox who was a fugitive from Operation Woodchuck. This was a year-long investigation that included an undercover ATF agent infiltrating a group of criminals who were selling illegal firearms and narcotics in the San Fernando Valley. During the course of the investigation, ATF undercover agents purchased stolen firearms, machine guns and silencers. Other agencies participating in Operation Woodchuck were the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), Office of Correctional Safety-Special Service Unit (CDCR- SSU), and the Los Angeles Police Department. The information from JSOC was provided to the local ATF field office in Fresno, CA. The Fresno ATF agents have been invaluable participants on the U.S. Marshals Central Valley Joint Fugitive Task Force (CVJFTF) in the Eastern District of California. On the same day the tip was received, members of the CVJFTF traveled the 135 miles from Fresno to Tehachapi in an effort to track down Knox. The task force, along with the Kern County Sheriff’s Department, responded to a remote location in the foot-hills of Tehachapi. The team was able to locate a residence where the subject was possibly staying. -

Fugitive Slaves and the Legal Regulation of Black Mississippi River Crossing, 1804–1860

Strengthening Slavery’s Border, Undermining Slavery: Fugitive Slaves and the Legal Regulation of Black Mississippi River Crossing, 1804–1860 BY JESSE NASTA 16 | The Confluence | Spring/Summer 2017 In 1873, formerly enslaved St. Louisan James master’s consent, or of the passenger’s free status, P. Thomas applied for a United States passport. persisted until the Civil War.3 After collecting the passport at his attorney’s office, Yet, while the text of the Missouri statute Thomas hurried home “to take a look at it” because remained fairly constant, its meaning changed over he had “never expected to see” his name on such a the six tumultuous decades between the Louisiana document. He marveled that this government-issued Purchase and the Civil War because virtually passport gave him “the right to travel where he everything else in this border region changed. The choose [sic] and under the protection of the American former Northwest Territory, particularly Illinois, flag.” As Thomas recalled in his 1903 autobiography, was by no means an automatic destination for those he spent “most of the night trying to realize the great escaping slavery. For at least four decades after the change that time had wrought.” As a free African Northwest Ordinance of 1787 nominally banned American in 1850s St. Louis, he had been able to slavery from this territory, the enslavement and cross the Mississippi River to Illinois only when trafficking of African Americans persisted there. “known to the officers of the boat” or if “two or three Although some slaves risked escape to Illinois, reliable citizens made the ferry company feel they enslaved African Americans also escaped from this were taking no risk in carrying me into a free state.”1 “free” jurisdiction, at least until the 1830s, as a result. -

MARGARET GARNER a New American Opera in Two Acts

Richard Danielpour MARGARET GARNER A New American Opera in Two Acts Libretto by Toni Morrison Based on a true story First performance: Detroit Opera House, May 7, 2005 Opera Carolina performances: April 20, 22 & 23, 2006 North Carolina Blumenthal Performing Arts Center Stefan Lano, conductor Cynthia Stokes, stage director The Opera Carolina Chorus The Charlotte Contemporary Ensemble The Charlotte Symphony Orchestra The Characters Cast Margaret Garner, mezzo slave on the Gaines plantation Denyce Graves Robert Garner, bass baritone her husband Eric Greene Edward Gaines, baritone owner of the plantation Michael Mayes Cilla, soprano Margaret’s mother Angela Renee Simpson Casey, tenor foreman on the Gaines plantation Mark Pannuccio Caroline, soprano Edward Gaines’ daughter Inna Dukach George, baritone her fiancée Jonathan Boyd Auctioneer, tenor Dale Bryant First Judge , tenor Dale Bryant Second Judge, baritone Daniel Boye Third Judge, baritone Jeff Monette Slaves on the Gaines plantation, Townspeople The opera takes place in Kentucky and Ohio Between 1856 and 1861 1 MARGARET GARNER Act I, scene i: SLAVE CHORUS Kentucky, April 1856. …NO, NO. NO, NO MORE! NO, NO, NO! The opera begins in total darkness, without any sense (basses) PLEASE GOD, NO MORE! of location or time period. Out of the blackness, a large group of slaves gradually becomes visible. They are huddled together on an elevated platform in the MARGARET center of the stage. UNDER MY HEAD... CHORUS: “No More!” SLAVE CHORUS THE SLAVES (Slave Chorus, Margaret, Cilla, and Robert) … NO, NO, NO MORE! NO, NO MORE. NO, NO MORE. NO, NO, NO! NO MORE, NOT MORE. (basses) DEAR GOD, NO MORE! PLEASE, GOD, NO MORE. -

RIVERFRONT CIRCULATING MATERIALS (Can Be Checked Out)

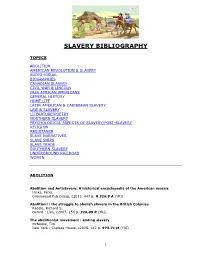

SLAVERY BIBLIOGRAPHY TOPICS ABOLITION AMERICAN REVOLUTION & SLAVERY AUDIO-VISUAL BIOGRAPHIES CANADIAN SLAVERY CIVIL WAR & LINCOLN FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS GENERAL HISTORY HOME LIFE LATIN AMERICAN & CARIBBEAN SLAVERY LAW & SLAVERY LITERATURE/POETRY NORTHERN SLAVERY PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF SLAVERY/POST-SLAVERY RELIGION RESISTANCE SLAVE NARRATIVES SLAVE SHIPS SLAVE TRADE SOUTHERN SLAVERY UNDERGROUND RAILROAD WOMEN ABOLITION Abolition and Antislavery: A historical encyclopedia of the American mosaic Hinks, Peter. Greenwood Pub Group, c2015. 447 p. R 326.8 A (YRI) Abolition! : the struggle to abolish slavery in the British Colonies Reddie, Richard S. Oxford : Lion, c2007. 254 p. 326.09 R (YRI) The abolitionist movement : ending slavery McNeese, Tim. New York : Chelsea House, c2008. 142 p. 973.71 M (YRI) 1 The abolitionist legacy: from Reconstruction to the NAACP McPherson, James M. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, c1975. 438 p. 322.44 M (YRI) All on fire : William Lloyd Garrison and the abolition of slavery Mayer, Henry, 1941- New York : St. Martin's Press, c1998. 707 p. B GARRISON (YWI) Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the heroic campaign to end slavery Metaxas, Eric New York, NY : Harper, c2007. 281p. B WILBERFORCE (YRI, YWI) American to the backbone : the life of James W.C. Pennington, the fugitive slave who became one of the first black abolitionists Webber, Christopher. New York : Pegasus Books, c2011. 493 p. B PENNINGTON (YRI) The Amistad slave revolt and American abolition. Zeinert, Karen. North Haven, CT : Linnet Books, c1997. 101p. 326.09 Z (YRI, YWI) Angelina Grimke : voice of abolition. Todras, Ellen H., 1947- North Haven, Conn. : Linnet Books, c1999. 178p. YA B GRIMKE (YWI) The antislavery movement Rogers, James T. -

1 United States District Court

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE AT CHATTANOOGA JAMES A. BARNETT, ) ) Plaintiff,) v. ) No. 1:06-cv-235 ) Edgar/Lee LENDA CLARK; KEN COX; ) DEPUTY SILER; SHERIFF BILLY LONG; ) JIM HART, CHIEF OF CORRECTIONS; ) HAMILTON DISTRICT ATTORNEY BILL ) COX; ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM James A. Barnett ("Plaintiff"), a former Tennessee inmate brings this pro se complaint for damages pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983, contending that he was illegally extradited to Tennessee in violation of his constitutional rights. Plaintiff has been released and now resides in Georgia (Court File # 67). The defendants are Lt. Lenda Clark ("Lt. Clark"), Ken Cox ("Deputy Cox"), Deputy Siler ("Deputy Siler"), Sheriff Billy Long ("Sheriff Long"), and Jim Hart, Chief of Corrections at Hamilton County Jail ("Chief Hart"). Hamilton County District Attorney Bill Cox was dismissed from this litigation by previous Order of this Court (Court File #53). Plaintiff asserts Defendants violated his constitutional rights when they extradited him from Georgia to Tennessee in absence of a signed Governor's extradition warrant, wavier of extradition rights, or habeas hearing. Plaintiff contends he is entitled to damages for these constitutional violations. Defendants contend that a violation of the procedures provided in the Uniform Criminal 1 Case 1:06-cv-00235 Document 76 Filed 01/22/08 Page 1 of 21 PageID #: <pageID> Extradition Act (“UCEA”), codified in Tennessee at Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-9-101 et. seq.1 does not create a cognizable constitutional claim under § 1983 in the Sixth Circuit and the release of Plaintiff in September of 2006 to the Hamilton County Sheriff’s Department is governed by the UCEA. -

Fugitive Dust

Fugitive Dust Why Control Fugitive Dust? Sources of Fugitive Dust Besides causing the need for additional Significant sources of fugitive dust include cleaning of homes and vehicles, fugitive dust grain bins, quarries, haul roads and can cause low visibility on unpaved roads, construction sites. which can lead to accidents. In severe cases, In the example of an unpaved road, fugitive Division of Compliance it can interfere with plant growth by clogging dust is created when a vehicle travels down pores and reducing light interception. Dust Assistance the unpaved road. The larger and faster the particles are abrasive to mechanical vehicle, the more dust it will create. One way 300 Sower Boulevard, First Floor equipment and damaging to electronic of controlling this is with dust suppression, equipment, such as computers. Frankfort, KY 40601 such as water or gravel, at the end of unpaved What Is Fugitive Dust? Phone: 502-564-0323 Although generally not toxic, fugitive dust roads. can cause health problems, alone or in Fugitive dust is defined as dust that is not Email: [email protected] emitted from definable point sources, such as combination with other air pollutants. dca.ky.gov industrial smokestacks. Sources include open Infants, the elderly and people with Dust from around the world! fields, roadways and storage piles. respiratory problems, such as asthma or bronchitis, are the most likely to be affected. Fugitive dust you create does not affect only The state regulation that provides for the In addition, not controlling fugitive dust at a those within close proximity to your location. control of fugitive emissions may be accessed worksite can create more hassle for the In a model of dust imports developed by at http://www.lrc.ky.gov/kar/ worksite foreman in response to complaints researchers from Harvard and NASA shows 401/063/010.htm.