1. Preliminary Materials Formatted (20191202)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

URBAN PLANNING and ENVIRONMENTAL LAW QUARTERLYQUARTERLY (Published Since May 1992)

An Association of Asian Commercial Law Firms FRED KAN & CO. Solicitors & Notaries URBAN PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENTAL LAW QUARTERLYQUARTERLY (Published since May 1992) We are confronted increasingly by examples of the government’s reluctance to fairly and resolutely enforce our planning and environment-protection laws: from slow or no reactions to illegal roads in country parks and bending planning laws to accommodate developers’ ambitions, to almost a state of denial of worsening air and water pollution. However, a long-standing record of inadequate penalties for environmental offences also contributes to this sorry state of affairs. The Editors ● WDO CONTENTS WEAK PENALTIES 1st offence - $200,000 and 6 months imprisonment UNDERMINE ENFORCEMENT 2nd (etc) offence - $500,000 and imprisonment for 6 months OF ENVIRONMENTAL LAWS ● WPCO FEATURE: Page We often hear and read criticism of the apparent lack of 1st offence - $200,000 and 6 months imprisonment political will in Hong Kong to monitor and resolutely 2nd (etc.) offence - $400,000 (plus $10,000 per day for WEAK PENALTIES UNDERMINE enforce our environment-protection and planning laws. continuing offence) and 6 months imprisonment Over the years, the UPELQ has from time to time made ENFORCEMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL the same criticism of Hong Kong’s environmental agencies, ● APCO LAWS ................................................................1 mainly in the context of anti-pollution laws and laws Section 10(7)(a) (failure to comply with abatement designed to protect our natural environment. notice) – fine of $500,000 (plus $100,000 per day for continuing TOWN PLANNING ...........................................3 We make no apology for doing so again. Specifically, in offence) and imprisonment for 12 months. -

Director of Administration's Letter Dated 12 May 2021

Enclosure A Press Statement Senior Judicial Appointment: Permanent Judge of the Court of Final Appeal ************************************************************** The Chief Executive, Mrs Carrie Lam, has accepted the recommendation of the Judicial Officers Recommendation Commission (JORC) on the appointment of the Honourable Mr Justice Johnson LAM Man-hon (Mr Justice Lam), Vice-President and Justice of Appeal of the Court of Appeal of the High Court, as a permanent judge of the Court of Final Appeal. Subject to the endorsement of the Legislative Council, the Chief Executive will make the appointment under Article 88 of the Basic Law. Mrs Lam said, “I am pleased to accept the JORC’s recommendation on the appointment of Mr Justice Lam as a permanent judge of the Court of Final Appeal. Mr Justice Lam is an all-rounded appellate Judge who possesses rich experience and expertise in handling civil cases of all types, including in particular public law and constitutional law cases. His judgments are well-reasoned and balanced. They are regularly reported in the law reports and cited in arguments and judgments. He also has extensive experience in steering reforms to improve on the administration of justice. He will be a great asset to the Court of Final Appeal.” Article 90 of the Basic Law provides that the Chief Executive shall obtain the endorsement of the Legislative Council on the appointment of the judges of the Court of Final Appeal. The Government will seek the endorsement of the Legislative Council of the recommended appointment in due course. The curriculum vitae of Mr Justice Lam is at Annex. -

ASAA Abstract Booklet

ASAA 2020 Abstract Book 23rd Biennial Conference of the Asian Studies Association of Australia (ASAA) The University of Melbourne Contents Pages ● Address from the Conference Convenor 3 ● 2020 ASAA Organising Committee 4 ● Disciplinary Champions 4-6 ● Conference Organisers 6 ● Conference Sponsors and Supporters 7 ● Conference Program 8-18 ● Sub-Regional Keynote Abstracts 19-21 ● Roundtable Abstracts 22-25 ● Speaker Abstracts ○ Tuesday 7th July ▪ Panel Session 1.1 26-60 ▪ Panel Session 1.2 61-94 ▪ Panel Session 1.3 95-129 ○ Wednesday 8th July ▪ Panel Session 2.1 130-165 ▪ Panel Session 2.2 166-198 ▪ Panel Session 2.3 199-230 ○ Thursday 9th July ▪ Panel Session 3.1 231-264 ▪ Panel Session 3.2 265-296 ▪ Panel Session 3.3 297-322 ● Author Index 323-332 Page 2 23rd Biennial Conference of the Asian Studies Association of Australia Abstract Book Address from the Conference Convenor Dear Colleagues, At the time that we made the necessary decision to cancel the ASAA 2020 conference our digital program was already available online. Following requests from several younger conference participants who were looking forward to presenting at their first international conference and networking with established colleagues in their field, we have prepared this book of abstracts together with the program. We hope that you, our intended ASAA 2020 delegates, will use this document as a way to discover the breadth of research being undertaken and reach out to other scholars. Several of you have kindly recognised how much work went into preparing the program for our 600 participants. We think this is a nice way to at least share the program in an accessible format and to allow you all to see the exciting breadth of research on Asia going on in Australia and in the region. -

Thanks for Your Support

Thanks for Your Support The Academy of Law acknowledges the generous contribution of everyone who was involved in the presentation of the training programme for the period between 2 September 2008 and 31 December 2009. The Academy extends a special note of thanks to the following judges, solicitors, barristers, foreign lawyers and prominent members of society who volunteered their time to make the programme such a success: A y Registrar Queeny Au-Yeung, High Court B y Peter Barnes, Partner, Barnes & Daly y Philip Beh, Associate Professor, Department of Pathology, The University of Hong Kong y Geoffrey Booth, Partner, Haldanes y Judge Kevin Browne, Judge of the District Court y John Budge, Partner, Wilkinson & Grist y Patrick Burke, Partner, Burke & Co C y Patrick Cavanagh, Director of Commercial Programmes, Dispute Resolution Centre, Bond University y His Honour Judge Bruno Chan, Family Court y Mary Chan, Consultant, Ho & Ip y Her Honour Judge Mimmie Chan, District Court y Stephen Chan, Partner, BDO Limited y Felix W.H. Chan, Associate Professor, Associate Dean, Department of Professional Legal Education, The University of Hong Kong y Wai-sum Chan, Professor, Department of Finance, Chinese University of Hong Kong y Julia Charlton, Partner, Charltons y Allen Che, Partner, Wong, Hui, & Co y Cheng Wui Kei Roy, Director, ISE Consultants Limited y Amelia Cheung, Partner, Amelia Cheung & Co y David Cheung, Partner, Yuen K H & David Cheung y Melissa Chim, Solicitor, Barlow Lyde & Gilbert y Choi Wai Fan, RBS Coutts Bank Ltd y Chow Wing Hang, -

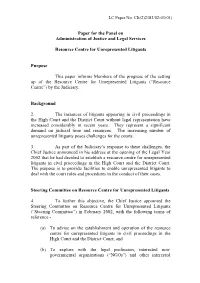

Cb(2)2183/02-03(01)

LC Paper No. CB(2)2183/02-03(01) Paper for the Panel on Administration of Justice and Legal Services Resource Centre for Unrepresented Litigants Purpose This paper informs Members of the progress of the setting up of the Resource Centre for Unrepresented Litigants (“Resource Centre”) by the Judiciary. Background 2. The instances of litigants appearing in civil proceedings in the High Court and the District Court without legal representation have increased considerably in recent years. They represent a significant demand on judicial time and resources. The increasing number of unrepresented litigants poses challenges for the courts. 3. As part of the Judiciary’s response to these challenges, the Chief Justice announced in his address at the opening of the Legal Year 2002 that he had decided to establish a resource centre for unrepresented litigants in civil proceedings in the High Court and the District Court. The purpose is to provide facilities to enable unrepresented litigants to deal with the court rules and procedures in the conduct of their cases. Steering Committee on Resource Centre for Unrepresented Litigants 4. To further this objective, the Chief Justice appointed the Steering Committee on Resource Centre for Unrepresented Litigants (“Steering Committee”) in February 2002, with the following terms of reference - (a) To advise on the establishment and operation of the resource centre for unrepresented litigants in civil proceedings in the High Court and the District Court; and (b) To explore with the legal profession, interested non- governmental organizations (“NGOs”) and other interested - 2 - bodies opportunities for them to provide assistance at or through the resource centre to unrepresented litigants in civil proceedings in the High Court and the District Court. -

Going to Court

GOING TO COURT A DISCUSSION PAPER ON CIVIL JUSTICE IN VICTORIA PETER A SALLMANN, CROWN COUNSEL AND RICHARD T WRIGHT, ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR, CIVIL JUSTICE REVIEW PROJECT APRIL, 2000 How to make comments and submissions We would encourage comments and submissions on the discussion paper. They can be sent to the Department of Justice at the address below: Civil Justice Review Project GPO Box 4356QQ Melbourne, Victoria, 3001 Comments and submissions can also be sent by e-mail to: [email protected] The discussion can be read and downloaded from the Department of Justice homepage www.justice.vic.gov.au Adobe Acrobat® Reader will be required. Peter Sallmann LLB (Melbourne), M.S.A.J. (The American University), M.Phil (Cambridge) is Victorian Crown Counsel, formerly Director of the Civil Justice Review Project, Executive Director of the Australian Institute of Judicial Administration and a Commissioner of the Law Reform Commission of Victoria. Peter is admitted to practise as a Barrister and Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Victoria. He has held a number of academic posts in law and criminology, and served on a variety of Boards and Inquiries, including the Premier’s Drug Advisory Council (the Penington Inquiry) and has published widely on judicial administration and related topics. Richard Wright B.Ec (Hons) (La Trobe) LLB (Melbourne) is Associate Director of the Civil Justice Review Project, formerly Chairman of the Residential Tenancies Tribunals and Senior Referee of the Small Claims Tribunal, Executive Director of the Law Reform Commission of Victoria, Management Consultant in the public and private sectors and has held policy advisory positions in the Australian Tariff Board, Prices Justification Tribunal and the federal Departments of Industrial Relations and Prime Minister and Cabinet. -

Hong Kong Book Catalogue

2021 Hong Kong July Book Catalogue ENCYCLOPAEDIC WORKS & LOOSELEAF SERVICES Law. In Sync. Title Index Encyclopaedic Works • Atkin's Court Forms Hong Kong • Halsbury's Laws of Hong Kong - Second Edition • The Annotated Ordinances of Hong Kong • The Hong Kong Encyclopaedia of Forms and Precedents Law Reports • Hong Kong Cases • Hong Kong Conveyancing and Property Reports • Hong Kong Family Law Reports • Hong Kong Public Law Reports Looseleafs • Banking Law: Hong Kong SAR and People's Republic of China • Butterworths Hong Kong Personal Injury Service • Criminal Evidence in Hong Kong • Criminal Procedure: Trial on Indictment • Emden's Construction Law Hong Kong • Encyclopaedia of Hong Kong Taxation • Hong Kong Civil Court Practice • Hong Kong Company Law: Legislation and Commentary • Hong Kong Conveyancing • Hong Kong Corporate Law • Hong Kong Employment Law Manual • Hong Kong Employment Ordinance: An Annotated Guide • Hotten and Ho on Family and Divorce Law in Hong Kong • Intellectual Property in Hong Kong • Securities Law: Hong Kong SAR and People's Republic of China • The Professional Conduct of Lawyers in Hong Kong LexisNexis® Hong Kong - Encyclopaedic Works & Looseleaf Services 2021 Atkin's Court Forms Hong Kong ISBN: Update frequency: 9789628105472 6 issues a year Format: Looseleaf set (10 binders); Lexis Advance® Hong Kong (Online) Scan me for details https://www.lexisnexis.com.hk/ACFHK An unrivalled collection of the main procedural documents required in every civil proceeding before the courts in Hong Kong. Your guide through all the essential stages of proceedings, from pre-action to post-judgment, providing a structured and reliable guide to help you plead with confidence. This essential practical encyclopaedia is the authoritative local version Titles Covered: of the UK encyclopaedic work, fully adapted to the needs of the Hong Kong practitioner. -

JORC Report 2018

JORC Report 2018 The work of the Judicial Officers Recommendation Commission (“JORC”) is set out in two separate reports. First, a report entitled “Judicial Officers Recommendation Commission” is published to provide an overall account of the JORC, identifying the different levels of court within its responsibility. Secondly, an annual report is published to report on the work of the JORC during the year. This JORC Report 2018 provides an account of the work of the JORC during 2018. In an effort to contribute to the protection of the environment, we will only upload both Reports on our Website. Geoffrey Ma Chief Justice Chairman of the Judicial Officers Recommendation Commission Membership of JORC 1. In 2018, the Chief Executive re-appointed a member of JORC and appointed five new members to JORC for a term of up to two years until 30 June 2020. The membership in 2018 is listed below – Ex officio chairman and member The Honourable Chief Justice Geoffrey MA Tao-li, GBM (Chairman) The Honourable Ms. Teresa CHENG Yeuk-wah, GBS, SC, JP (Secretary for Justice) Judges The Honourable Mr. Justice Robert TANG Ching, GBM, SBS (from 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2016) (from 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2018) The Honourable Mr. Justice Andrew CHEUNG Kui-nung (from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2014) (from 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2016) (from 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2018) (from 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2020) The Honourable Madam Justice Carlye CHU Fun-ling (from 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2020) Barrister and solicitor Ms. -

Opening of the Legal Yew; 2002

Opening of the legal Yew; 2002 Chapter In the Eyes of_ the Law he rule of law has provided Hong Kong with a level playing field for Tfree and fair competition, and hence helped maintain the integrity of a genuine market economy. It is also the firm foundation for the freedoms that Hong Kong enjoys. The security and stability that our system of laws has provided have made Hong Kong a major attraction for investments and arguably the most cosmopolitan city in the region. Hong Kong's legal system is essentially a British tradition of rigour that has taken root in a Chinese culture. The credit for taking relative comfort in such a potentially difficult combination should go to the handful of earlier local members of the profession. Among them, the University's graduates, often receiving their legal training overseas, but benefiting from their liberal education at the University, have played an important part. The cultural integration in the legal system has given Hong Kong's legal profession the privileged position of being able to participate in the reconstruction of China's legal system out of the ruins of the Cultural Revolution, and is crucial to Hong Kong playing a bridging role between those inside and outside China. The first generation of locally educated lawyers emerged in 1972. as the first law graduates of the University. Since then, the University's law graduates have played pivotal roles in Hong Kong's participation in the drafting of the Basic Law which is the mini-constitution for the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. -

JORC Report 2019

JORC Report 2019 The work of the Judicial Officers Recommendation Commission (“JORC”) is set out in two separate reports. First, a report entitled “Judicial Officers Recommendation Commission” is published to provide an overall account of the JORC, identifying the different levels of court within its responsibility. Secondly, an annual report is published to report on the work of the JORC during the year. This JORC Report 2019 provides an account of the work of the JORC during 2019. In an effort to contribute to the protection of the environment, we will only upload both Reports on our Website. Geoffrey Ma Chief Justice Chairman of the Judicial Officers Recommendation Commission Membership of JORC 1. In 2019, the Chief Executive re-appointed a member of JORC and appointed a new member to JORC for a term of up to two years until 30 June 2021. The membership in 2019 is listed below – Ex officio chairman and member The Honourable Chief Justice Geoffrey MA Tao-li, GBM (Chairman) The Honourable Ms. Teresa CHENG Yeuk-wah, GBS, SC, JP (Secretary for Justice) Judges The Honourable Mr. Justice Andrew CHEUNG Kui-nung (from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2014) (from 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2016) (from 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2018) (from 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2020) The Honourable Madam Justice Carlye CHU Fun-ling (from 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2020) Barrister and solicitor Mr. Philip John DYKES, SC (barrister) (from 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2020) Mr. Stephen HUNG Wan-shun (solicitor) (from 1 July 2015 to 30 June 2017) (from 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2019) Dr. -

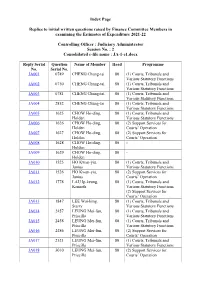

Index Page Replies to Initial Written Questions Raised by Finance

Index Page Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2021-22 Controlling Officer : Judiciary Administrator Session No. : 2 Consolidated e-file name : JA-1-e1.docx Reply Serial Question Name of Member Head Programme No. Serial No. JA001 0749 CHENG Chung-tai 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA002 0750 CHENG Chung-tai 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA003 0781 CHENG Chung-tai 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA004 2852 CHENG Chung-tai 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA005 1625 CHOW Ho-ding, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Holden Various Statutory Functions JA006 1626 CHOW Ho-ding, 80 (2) Support Services for Holden Courts’ Operation JA007 1627 CHOW Ho-ding, 80 (2) Support Services for Holden Courts’ Operation JA008 1628 CHOW Ho-ding, 80 - Holden JA009 1629 CHOW Ho-ding, 80 - Holden JA010 1525 HO Kwan-yiu, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Junius Various Statutory Functions JA011 1526 HO Kwan-yiu, 80 (2) Support Services for Junius Courts’ Operation JA012 1778 LAU Ip-keung, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Kenneth Various Statutory Functions (2) Support Services for Courts’ Operation JA013 1847 LEE Wai-king, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Starry Various Statutory Functions JA014 2457 LEUNG Mei-fun, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Priscilla Various Statutory Functions JA015 2458 LEUNG Mei-fun, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Priscilla Various Statutory Functions JA016 2486 LEUNG Mei-fun, 80 (2) Support Services for Priscilla Courts’ Operation JA017 2521 LEUNG Mei-fun, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Priscilla Various Statutory Functions JA018 3010 LEUNG Mei-fun, 80 (2) Support Services for Priscilla Courts’ Operation Reply Serial Question Name of Member Head Programme No. -

Director of Administration's Letter Dated 22 May 2019

Enclosure A Press Statement Senior Judicial Appointment: Non-Permanent Judge from Another Common Law Jurisdiction of the Court of Final Appeal ************************************************************** The Chief Executive, Mrs Carrie Lam, has accepted the recommendation of the Judicial Officers Recommendation Commission (JORC) on the appointment of the Right Honourable Lord Jonathan Sumption (Lord Sumption) as a non-permanent judge from another common law jurisdiction of the Court of Final Appeal. Subject to the endorsement of the Legislative Council, the Chief Executive will make the appointment under Article 88 of the Basic Law. Mrs Lam said, “I am pleased to accept the JORC’s recommendation to appoint Lord Sumption as a non-permanent judge from another common law jurisdiction of the Court of Final Appeal. Lord Sumption was a Justice of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom since January 2012 until he retired from the office in December 2018. He is a judge of eminent standing and reputation. I am confident that he will be a great asset to the Court of Final Appeal.” “With the appointment of Lord Sumption, the panel of non- permanent judges from other common law jurisdictions will consist of 15 eminent judges from the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada. The presence of these non-permanent judges manifests the judicial independence of Hong Kong,” Mrs Lam said. The Court of Final Appeal is constituted by five judges when hearing and determining appeals. Since 1 July 1997, apart from very few exceptions, one of the judges has invariably been drawn from the list of non- permanent judges from other common law jurisdictions to hear a substantive appeal on the Court of Final Appeal.