Gest, Chapter 2 Arquivo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dinosaurs and Donkeys: British Tabloid Newspapers

DINOSAURS AND DONKEYS: BRITISH TABLOID NEWSPAPERS AND TRADE UNIONS, 2002-2010 By RYAN JAMES THOMAS A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY The Edward R. Murrow College of Communication MAY 2012 © Copyright by RYAN JAMES THOMAS, 2012 All rights reserved © Copyright by RYAN JAMES THOMAS, 2012 All Rights Reserved To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of RYAN JAMES THOMAS find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. __________________________________________ Elizabeth Blanks Hindman, Ph.D., Chair __________________________________________ Douglas Blanks Hindman, Ph.D. __________________________________________ Michael Salvador, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation, not to mention my doctoral degree, would not be possible with the support and guidance of my chair, Dr. Elizabeth Blanks Hindman. Her thoughtful and thorough feedback has been invaluable. Furthermore, as both my MA and doctoral advisor, she has been a model of what a mentor and educator should be and I am indebted to her for my development as a scholar. I am also grateful for the support of my committee, Dr. Douglas Blanks Hindman and Dr. Michael Salvador, who have provided challenging and insightful feedback both for this dissertation and throughout my doctoral program. I have also had the privilege of working with several outstanding faculty members (past and present) at The Edward R. Murrow College of Communication, and would like to acknowledge Dr. Jeff Peterson, Dr. Mary Meares, Professor Roberta Kelly, Dr. Susan Dente Ross, Dr. Paul Mark Wadleigh, Dr. Prabu David, and Dr. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Political Reactions to Changes in Local Economic Policies Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0679c5mm Author Fukumoto, Makoto Publication Date 2021 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Political Reactions to Changes in Local Economic Policies By Makoto Fukumoto A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California. Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Paul Pierson, Co-Chair Professor Sarah Anzia, Co-Chair Professor Ernesto Dal B`o Professor Alison Post Professor Frederico Finan Spring 2021 Abstract Political Reactions to Changes in Local Economic Policies by Makoto Fukumoto Doctor in Philosophy in Political Science University of California. Berkeley Professor Paul Pierson, Co-Chair Professor Sarah Anzia, Co-Chair Against the backdrop of accelerating economic divergence across different regions in advanced economies, political scientists are increasingly interested in its implication on political behavior and public opinion. This dissertation presents three papers that show how local-level implementation of policies and local economic circumstances affect voters' behavior. The first paper, titled \Biting the Hands that Feed Them? Place-Based Policies and Decline of Local Support", analyzed if place-based policies such as infrastructure projects and business support can garner political support in the area, using the EU funding data in the UK. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the findings suggest that relatively educated, well-off voters who pay attention to local affairs turn against the government that provides such programs and become more interested in the budgeting process. -

The Cultural Politics of Climate Change Discourse in UK Tabloids

Author's personal copy Political Geography 27 (2008) 549e569 www.elsevier.com/locate/polgeo The cultural politics of climate change discourse in UK tabloids Maxwell T. Boykoff* James Martin Research Fellow, Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3QY, UK Abstract In the United Kingdom (UK), daily circulation figures for tabloid newspapers are as much as ten times higher than broadsheet sources. Nonetheless, studies of media representations of climate change in the UK to date have focused on broadsheet newspapers. Moreover, readership patterns correlate with socio-eco- nomic status; the majority of readers of tabloids are in ‘working class’ demographics. With a growing need to engage wider constituencies in awareness and potential behavioral change, it is important to ex- amine how these influential sources represent climate change for a heretofore understudied segment of citizenry. This paper links political geographies with cultural issues of identity and discourse, through claims and frames on climate change in four daily ‘working class’ tabloid newspapers in UK e The Sun (and News of the World ), Daily Mail (and Mail on Sunday), the Daily Express (and Sunday Express), and the Mirror (and Sunday Mirror). Through triangulated Critical Discourse Analysis, investigations of framing and semi-structured interviews, this project examines representations of climate change in these newspapers from 2000 through 2006. Data show that news articles on climate change were predominantly framed through weather events, charismatic megafauna and the movements of political actors and rhetoric, while few stories focused on climate justice and risk. In addition, headlines with tones of fear, misery and doom were most prevalent. -

Challenging Collections

Insights and Experiments Interview with Thomas Söderqvist Söderqvist, Thomas Published in: Challenging Collections DOI: 10.5479/si.9781944466121 Publication date: 2017 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: Unspecified Citation for published version (APA): Söderqvist, T. (2017). Insights and Experiments: Interview with Thomas Söderqvist. In A. Boyle, & J-G. Hagmann (Eds.), Challenging Collections: Approaches to the Heritage of Recent Science and Technology (pp. 228-231). Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press. Artefacts: Studies in the History of Science and Technology Vol. 11 https://doi.org/10.5479/si.9781944466121 Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 https:// Boyle and Hagmann artefacts science and technology of studies in the history Volume 11 Managing Editor Martin Collins, Smithsonian Institution Series Editors Robert Bud, Science Museum, London Bernard Finn, Smithsonian Institution Helmuth Trischler, Deutsches Museum his most recent volume in the Artefacts series, Challenging Collections: Ap- Challenging Collections Tproaches to the Heritage of Recent Science and Technology, focuses on the question of collecting post–World War II scientific and technological heritage in museums, and the challenging issue of how such artifacts can be displayed and interpreted for diverse publics. In addition to examples of practice, editors Alison Boyle and Johannes-Geert Hagmann have invited prominent historians and cura- tors to reflect on the nature of recent scientific and technological heritage, and to challenge the role of museum collections in the twenty-first century. Challenging Collections will certainly be part of an ever-evolving dialogue among communities of collectors and scholars seeking to keep pace with the changing landscapes of sci- ence and technology, museology, and historiography. -

The Last Horizons of Roman Gaul: Communication, Community, and Power at the End of Antiquity

The Last Horizons of Roman Gaul: Communication, Community, and Power at the End of Antiquity The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Wilkinson, Ryan Hayes. 2015. The Last Horizons of Roman Gaul: Communication, Community, and Power at the End of Antiquity. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17467211 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Last Horizons of Roman Gaul: Communication, Community, and Power at the End of Antiquity A dissertation presented by Ryan Hayes Wilkinson to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Ryan Hayes Wilkinson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Michael McCormick Ryan Hayes Wilkinson The Last Horizons of Roman Gaul: Communication, Community, and Power at the End of Antiquity Abstract In the fifth and sixth centuries CE, the Roman Empire fragmented, along with its network of political, cultural, and socio-economic connections. How did that network’s collapse reshape the social and mental horizons of communities in one part of the Roman world, now eastern France? Did new political frontiers between barbarian kingdoms redirect those communities’ external connections, and if so, how? To address these questions, this dissertation focuses on the cities of two Gallo-Roman tribal groups. -

9781317587255.Pdf

Global Metal Music and Culture This book defines the key ideas, scholarly debates, and research activities that have contributed to the formation of the international and interdisciplinary field of Metal Studies. Drawing on insights from a wide range of disciplines including popular music, cultural studies, sociology, anthropology, philos- ophy, and ethics, this volume offers new and innovative research on metal musicology, global/local scenes studies, fandom, gender and metal identity, metal media, and commerce. Offering a wide-ranging focus on bands, scenes, periods, and sounds, contributors explore topics such as the riff-based song writing of classic heavy metal bands and their modern equivalents, and the musical-aesthetics of Grindcore, Doom and Drone metal, Death metal, and Progressive metal. They interrogate production technologies, sound engi- neering, album artwork and band promotion, logos and merchandising, t-shirt and jewelry design, and the social class and cultural identities of the fan communities that define the global metal music economy and subcul- tural scene. The volume explores how the new academic discipline of metal studies was formed, while also looking forward to the future of metal music and its relationship to metal scholarship and fandom. With an international range of contributors, this volume will appeal to scholars of popular music, cultural studies, social psychology and sociology, as well as those interested in metal communities around the world. Andy R. Brown is Senior Lecturer in Media Communications at Bath Spa University, UK. Karl Spracklen is Professor of Leisure Studies at Leeds Metropolitan Uni- versity, UK. Keith Kahn-Harris is honorary research fellow and associate lecturer at Birkbeck College, UK. -

Health Equity in England : the Marmot Review 10 Years On

HEALTH EQUITY IN ENGLAND: THE MARMOT REVIEW 10 YEARS ON HEALTH EQUITY IN ENGLAND: THE MARMOT REVIEW 10 YEARS ON HEALTH EQUITY IN ENGLAND: THE MARMOT REVIEW 10 YEARS ON 1 Note from the Chair AUTHORS Report writing team: Michael Marmot, Jessica Allen, Tammy Boyce, Peter Goldblatt, Joana Morrison. The Marmot Review team was led by Michael Marmot and Jessica Allen and consisted of Jessica Allen, Matilda Allen, Peter Goldblatt, Tammy Boyce, Antiopi Ntouva, Joana Morrison, Felicity Porritt. Peter Goldblatt, Tammy Boyce and Joana Morrison coordinated production and analysis of tables and charts. Team support: Luke Beswick, Darryl Bourke, Kit Codling, Patricia Hallam, Alice Munro. The work of the Review was informed and guided by the Advisory Group and the Health Foundation. Suggested citation: Michael Marmot, Jessica Allen, Tammy Boyce, Peter Goldblatt, Joana Morrison (2020) Health equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 years on. London: Institute of Health Equity HEALTH FOUNDATION The Health Foundation supported this work and provided insight and advice. IHE would like to thank in particular: Jennifer Dixon, Jo Bibby, Jenny Cockin, Tim Elwell Sutton, Grace Everest, David Finch Adam Tinson, Rita Ranmal. AUTHORS’ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are indebted to the Advisory Group that informed the review: Torsten Bell, David Buck, Sally Burlington, Jabeer Butt, Jo Casebourne, Adam Coutts, Naomi Eisenstadt, Joanne Roney, Frank Soodeen, Alice Wiseman. We are also grateful for advice and insight from the Collaboration for Health and Wellbeing. We are grateful for advice and input from Nicky Hawkins, Frameworks Institute; Angela Donkin, NFER; and Tom McBride, Early Intervention Foundation for comments on drafts. -

Violent Extremist Tactics and the Ideology of the Sectarian Far Left

Copyright © 2019 Daniel Allington, Siobhan McAndrew, and David Hirsh About the authors Daniel Allington is Senior Lecturer in Social and Cultural Artificial Intelligence at King’s College London and Deputy Editor of Journal of Contemporary Antisemitism. Siobhan McAndrew is Lecturer in Sociology with Quantitative Research Methods at the University of Bristol. David Hirsh is Senior Lecturer in Sociology at GoldsMiths, University of London and the author of Law against genocide: cosmopolitan trials (Glasshouse Press, 2003) and Contemporary left antisemitism (Routledge, 2017). Acknowledgements The fieldwork for this study was funded with a grant from the UK ComMission for Countering ExtreMisM, which also arranged for independent expert peer review of the research and for online publication of the current document. The ComMission had no role in the design and conduct of the research. Table of contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Definitions: what the sectarian far left is ...................................................................................... 2 1.2 Ideologies: what the sectarian far left believes ............................................................................. 2 1.3 Tactics: what the sectarian far left does ....................................................................................... -

Media Literacy Strategy

DEPARTMENT FOR DIGITAL, CULTURE, MEDIA & SPORT ONLINE SAFETY - MEDIA LITERACY STRATEGY Mapping Exercise and Literature Review - Phase 2 Report April 2021 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study was carried out for DCMS by RSM UK Consulting LLP, with support from the Centre for Excellence in Media Practice at Bournemouth University (CEMP). The RSM project team comprised Jenny Irwin (Partner), Matt Rooke (Project Manager), Beth Young (Managing Consultant), Amy Hau, Emma Liddell, and Matt Stephenson (Consultants). Our academic project advisors from CEMP were Professor Julian McDougall (Professor in Media and Education and Head of CEMP), Dr Isabella Rega (Principal Academic in Digital Literacies and Education and Deputy Head of CEMP), and Dr Richard Wallis (Principal Academic in CEMP). We are grateful to the project steering group at DCMS and to all the providers of digital media literacy initiatives and wider stakeholders who were interviewed for this study or who completed our online surveys. 2 CONTENTS 1. 4 2. 5 3. 9 4. 44 5. 59 3 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction RSM UK Consulting LLP was commissioned by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) to analyse online media literacy initiatives for United Kingdom (UK) users. The findings presented in this report provide a factual overview of existing provision in the UK, and any evaluations which accompanied existing initiatives or providers. This research aims to support a commitment set out in the ‘Online Harms White Paper’1 for the Government to develop an online media literacy strategy and contribute to its objectives to empower users to understand and manage risks so that they can stay safe online. -

The Rhetoric of Recessions

The rhetoric of recessions: how British newspapers talk about the poor when unemployment rises, 1896–2000 LSE Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/100546/ Version: Accepted Version Article: McArthur, Daniel and Reeves, Aaron (2019) The rhetoric of recessions: how British newspapers talk about the poor when unemployment rises, 1896–2000. Sociology, 53 (6). 1005 - 1025. ISSN 0038-0385 https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038519838752 Reuse Items deposited in LSE Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the LSE Research Online record for the item. [email protected] https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/ March 2019. Forthcoming in Sociology. T : B , 86-* Daniel McArthur† and Aaron Reeves‡ March 8, 2019 Abstract: Recessions appear to coincide with an increasingly stigmatising presentation of poverty in parts of the media. Previous research on the connection between high unemployment andmediadiscoursehasoftenreliedoncasestudiesofperiodswhen stigmatising rhetoric about the poor was increasing. We build on earlier work on how economic context affects media representations of poverty by creating a unique dataset that measures how often stigmatisingdescriptionsofthepoorareusedinfivecentrist and right-wing British news- papers between 1896 and 2000. Our results suggest stigmatising rhetoric about the poor increases when unemployment rises, except at the peak of very deep recessions (e.g. the 1930s and 1980s). This pattern is consistent with the idea that newspapers deploy deeply embedded Malthusian explanations for poverty when those ideas resonate with the eco- nomic context, and so this stigmatising rhetoric of recessions is likely to recur during future economic crises. -

Political Reactions to Changes in Local Economic Policies by Makoto

Political Reactions to Changes in Local Economic Policies By Makoto Fukumoto A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California. Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Paul Pierson, Co-Chair Professor Sarah Anzia, Co-Chair Professor Ernesto Dal B`o Professor Alison Post Professor Frederico Finan Spring 2021 Abstract Political Reactions to Changes in Local Economic Policies by Makoto Fukumoto Doctor in Philosophy in Political Science University of California. Berkeley Professor Paul Pierson, Co-Chair Professor Sarah Anzia, Co-Chair Against the backdrop of accelerating economic divergence across different regions in advanced economies, political scientists are increasingly interested in its implication on political behavior and public opinion. This dissertation presents three papers that show how local-level implementation of policies and local economic circumstances affect voters' behavior. The first paper, titled \Biting the Hands that Feed Them? Place-Based Policies and Decline of Local Support", analyzed if place-based policies such as infrastructure projects and business support can garner political support in the area, using the EU funding data in the UK. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the findings suggest that relatively educated, well-off voters who pay attention to local affairs turn against the government that provides such programs and become more interested in the budgeting process. Visible and high-profile projects appear to be particularly counterproductive. This goes against the positive findings in the literature about cash transfer or disaster relief, but it is important to remind that very few cases of such place-based intervention have been successful in the context of deflationary spirals in the declining regions. -

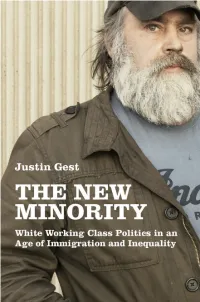

The New Minority

The New Minority The New Minority White Working Class Politics in an Age of Immigration and Inequality JUSTIN GEST 1 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America. © Oxford University Press 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Gest, Justin, author. Title: The new minority : white working class politics in an age of immigration and inequality / Justin Gest. Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016010130 (print) | LCCN 2016022736 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190632540 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780190632557 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780190632564 (Updf) | ISBN 9780190632571 (Epub) Subjects: LCSH: Working class—Political activity—Great Britain. | Working class—Political activity— United States.