Harry Wills and the Image of the Black Boxer from Jack Johnson to Joe Louis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harry Wills and the Image of the Black Boxer from Jack Johnson to Joe Louis

Harry Wills and the Image of the Black Boxer from Jack Johnson to Joe Louis B r i a n D . B u n k 1- Department o f History University o f Massachusetts, Amherst The African-American press created images o f Harry Will: that were intended to restore the image o f the black boxer afterfack fohnson and to use these positive representations as effective tools in the fight against inequality. Newspapers high lighted Wills’s moral character in contrast to Johnsons questionable reputation. Articles, editorials, and cartoons presented Wills as a representative o f all Ameri cans regardless o f race and appealed to notions o f sportsmanship based on equal opportunity in support o f the fighter's efforts to gain a chance at the title. The representations also characterized Wills as a race man whose struggle against boxings color line was connected to the larger challengesfacing all African Ameri cans. The linking o f a sportsfigure to the broader cause o f civil rights would only intensify during the 1930s as figures such as Joe Louis became even more effec tive weapons in the fight against Jim Crow segregation. T h e author is grateful to Jennifer Fronc, John Higginson, and Christopher Rivers for their thoughtful comments on various drafts of this essay. He also wishes to thank Steven A. Riess, Lew Erenberg, and Jerry Gems who contribu:ed to a North American Society for Sport History (NASSH) conference panel where much of this material was first presented. Correspondence to [email protected]. I n W HAT WAS PROBABLY T H E M O ST IMPORTANT mixed race heavyweight bout since Jim Jeffries met Jack Johnson, Luis Firpo and Harry Wills fought on September 11, 1924, at Boyle s Thirty Acres in Jersey City, New Jersey. -

Before Jackie Robinson Gerald R

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and University of Nebraska Press Chapters 2017 Before Jackie Robinson Gerald R. Gems Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Gems, Gerald R., "Before Jackie Robinson" (2017). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 359. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/359 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. BEFORE JACKIE ROBINSON Buy the Book Buy the Book Before Jackie Robinson The Transcendent Role of Black Sporting Pioneers Edited and with an introduction by GERALD R. GEMS University of Nebraska Press LINCOLN & LONDON Buy the Book © 2017 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska Portions of chapter 1 previously appeared in Pellom McDaniels III, The Prince of Jockeys: The Life of Isaac Burns Murphy (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2013). Used with permission. All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956312 Set in Minion Pro by Rachel Gould. Buy the Book CONTENTS Introduction . 1 Gerald R. Gems 1. Like a Comet across the Heavens: Isaac Burns Murphy, Horseracing, and the Age of American Exceptionalism . 17 Pellom McDaniels III 2. John M. Shippen Jr.: Testing the Front Nine of American Golf . 41 Sarah Jane Eikleberry 3. When Great Wasn’t Good Enough: Sam Ransom’s Journey from Athlete to Activist . -

EAST LAKE LUNCH ROOM Was Schooling Flowers Wr Ho Had Been at Work in the Shipyards in That City, SOUTHERN COOKING Happened to Drop Into the Gymna- Sium

Page Eleven PHOENIX TRIBUNE—ALWAYS IMPROVING by couldn’t help but brag a little about and he won over the champion a Tiger Flowers’ Climb what a fine boxer her husband was. big margin in a no-decision contest. From Obscurity Was “Didn’t Mr. O’Brien say so himself?” Then came the bouts with Jack A local promoter hearing of this Delaney. Flowers seems made to That of a Thorobred persuaded the “Tiger” to take a try order for Delaney, but despite the at professional fighting and in one quick knockouts suffered in these God Fearing Parents and Good Wife of his earliest bouts Flowers broke contests, Flowers was in no whit Figured Prominently in Success. his right hand. Which, incidentally, discouraged. These were the only Is Also a Musician. is how he came to change about to defeats he has suffered in the last “Tiger” Flowers credits his ob- his southpaw style of fighting*, three years. servance of the rules of careful liv- Gets First “K. O.” Habits ing and big reliance on religion as Has Good Then Walk Miller, who owned a the things that have counted strong- Despite the lack of early advan- gymnasium at Atlanta, got interest- er in his climb to the title of world’s tages Flowers has learned to play ed in Flowers and gave him a job middleweight champion* He makes both the violin and saxophone and as porter and started him off fight- it a practice to read three verses of Rls greatest pleasure in life is when morning ing in earnest. -

The Cambridge Companion to Boxing Edited by Gerald Early Frontmatter More Information I

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05801-9 — The Cambridge Companion to Boxing Edited by Gerald Early Frontmatter More Information i The Cambridge Companion to Boxing While humans have used their hands to engage in combat since the dawn of man, boxing originated in ancient Greece as an Olympic event. It is one of the most popular, controversial, and misunderstood sports in the world. For its advocates, it is a heroic expression of unfettered individualism. For its critics, it is a depraved and ruthless physical and commercial exploitation of mostly poor young men. This Companion offers engaging and informative chapters about the social impact and historical importance of the sport of boxing. It includes a comprehensive chronology of the sport, listing all the important events and per- sonalities. Chapters examine topics such as women in boxing, boxing and the rise of television, boxing in Africa, boxing and literature, and boxing and Hollywood fi lms. A unique book for scholars and fans alike, this Companion explores the sport from its inception in ancient Greece to the death of its most celebrated fi gure, Muhammad Ali. Gerald Early is Professor of English and African American Studies at Washington University in St. Louis. He has written about boxing since the early 1980s. His book, The Culture of Bruising , won the 1994 National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism. He also edited The Muhammad Ali Reader and Body Language: Writers on Sports . His essays have appeared several times in the Best American Essays series. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05801-9 — The Cambridge Companion to Boxing Edited by Gerald Early Frontmatter More Information ii © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05801-9 — The Cambridge Companion to Boxing Edited by Gerald Early Frontmatter More Information iii THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO BOXING EDITED BY GERALD EARLY Washington University, St. -

Analysis of Male Boxers' Nicknames

THE JOURNAL OF TEACHING ENGLISH FOR SPECIFIC AND ACADEMIC PURPOSES Vol. 6, No 1, 2018, pp. 126 UDC: 81‟1/‟4:796 https://doi.org/10.22190/JTESAP1801001O ANALYSIS OF MALE BOXERS’ NICKNAMES Darija Omrčen1, Hrvoje Pečarić2 1University of Zagreb, Faculty of Kinesiology, Croatia E-Mail: [email protected] 2Primary school Andrija Palmović, Rasinja, Croatia E-Mail: [email protected] Abstract. Nicknaming of individual athletes and sports teams is a multifaceted phenomenon the analysis of which reveals numerous reasons for choosing a particular name or nickname. The practice of nicknaming has become so embedded in the concept of sport that it requires exceptional attention by those who create these labels. The goal of this research was to analyse the semantic structure of boxers’ nicknames, i.e. the possible principles of their formation. To realize the research aims 378 male boxers’ nicknames, predominantly in the English language, were collected. The nicknames were allocated to semantic categories according to the content area or areas they referred to. Counts and percentages were calculated for the nicknames in each subsample created with regard to the number of semantic categories used to create a boxer’s nickname and for the group of nicknames allocated to the miscellaneous group. Counts were calculated for all groups within each subsample. Key words: hero, association, figurative language, figures of speech 1. INTRODUCTION Are nicknames only arbitrary formations of little account or are they coinages contrived meticulously and with a lot of prowess? Skipper (1989, 103) alleges that nicknames “often serve as a miniature character sketch”. When discussing nicknames in baseball, Gmelch (2006, 129) elucidates that sobriquets frequently communicate something about the players using them, e.g. -

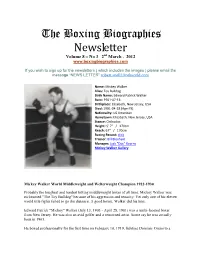

The Boxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 8 – No 3 2Nd March , 2012

The Boxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 8 – No 3 2nd March , 2012 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to sign up for the newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] Name: Mickey Walker Alias: Toy Bulldog Birth Name: Edward Patrick Walker Born: 1901-07-13 Birthplace: Elizabeth, New Jersey, USA Died: 1981-04-28 (Age:79) Nationality: US American Hometown: Elizabeth, New Jersey, USA Stance: Orthodox Height: 5′ 7″ / 170cm Reach: 67″ / 170cm Boxing Record: click Trainer: Bill Bloxham Manager: Jack "Doc" Kearns Mickey Walker Gallery Mickey Walker World Middleweight and Welterweight Champion 1922-1930 Probably the toughest and hardest hitting middleweight boxer of all time, Mickey Walker was nicknamed "The Toy Bulldog" because of his aggression and tenacity. Yet only one of his eleven world title fights failed to go the distance. A good boxer, Walker did his best. Edward Patrick "Mickey" Walker (July 13, 1903 - April 28, 1981) was a multi-faceted boxer from New Jersey. He was also an avid golfer and a renowned artist. Some say he was actually born in 1901. He boxed professionally for the first time on February 10, 1919, fighting Dominic Orsini to a four round no-decision in his hometown of Elizabeth, New Jersey. Walker did not venture from Elizabeth until his eighteenth bout, he went to Newark. On April 29 of 1919, he was defeated by knockout in round one by K.O. Phil Delmontt, suffering his first defeat. In 1920, he boxed twelve times, winning two and participating in ten no-decisions. -

Mt PERSHING and PARK APPEAR Leq

NET PRESS R m AVERAGE DAILY CIRCULATIOX' THR WEATHER* OF THE EVEI^mO HERALD for the month of September, 10S6. Fair and warmer tonight. Wed m t nesday cloudy and warmer, follow 4,849 ed by showers. rOL. XLV., NO. 10. OlassUled Adrertislng on Page 6 MANCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY, OCTOBER 12, 1926. (T)^ PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS 9TS.000 TO BE ONE IfEAR’S I l i m FRENCH CROWN ROSE 1 PAY FOR KING OF SW-4T . DlAhfOND IS STOLEN j HeV Ftght ^ PERSHING AND DAUGHERHAND r NEAR RIOT AS New York, Oct. 12.— Accord . Paris, Oct. 12.— ^The Samoun ing to reports in circulation to rose diamond, qne of the jewels day, Babe Ruth will be tendered Arid Bad, Says of the crown of. France and a PARK APPEAR a contract for next season call MHIERFREEAS ' w A l I i ;. .world' famous gem, was among LAWTEARSBOY ing for 175,000, the highest sal the loot ta'ken by thieves who ary paid any man in baseball, ■■ehtered the’ Grahd Conde Muse lE Q ^C H O IC E player, manager or league presi JDRYJSHONG New York, Oct. 12.^^Mk'De'pii>.<^ good Of bad.. I don’t expect to um during th'e night, the police FROMJQTHER' dent. The contract will be for sey,: deposed.. , . ^haavyw:elglit boxlnf I mpy lose some. ahhpunced today. '. one year only, it was said. champion, x^iil fight bis why h&c)k tp Dnt:,I waht. to Uit; m7 fighting m ^- Th'e" thieves, who entered Ruth’s last contract, which was a bout for the heavyweight' eham- Ge aivd . -

Boxing a Cultural History

A CULTURAL HISTORY KASIA BODDY 001_025_Boxing_Pre+Ch_1 25/1/08 15:37 Page 1 BOXING 001_025_Boxing_Pre+Ch_1 25/1/08 15:37 Page 2 001_025_Boxing_Pre+Ch_1 25/1/08 15:37 Page 3 BOXING A CULTURAL HISTORY KASIA BODDY reaktion books 001_025_Boxing_Pre+Ch_1 25/1/08 15:37 Page 4 For David Published by Reaktion Books Ltd 33 Great Sutton Street London ec1v 0dx www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2008 Copyright © Kasia Boddy 2008 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Printed and bound in China British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Boddy, Kasia Boxing : a cultural history 1. Boxing – Social aspects – History 2. Boxing – History I. Title 796.8’3’09 isbn 978 1 86189 369 7 001_025_Boxing_Pre+Ch_1 25/1/08 15:37 Page 5 Contents Introduction 7 1 The Classical Golden Age 9 2 The English Golden Age 26 3 Pugilism and Style 55 4 ‘Fighting, Rightly Understood’ 76 5 ‘Like Any Other Profession’ 110 6 Fresh Hopes 166 7 Sport of the Future 209 8 Save Me, Jack Dempsey; Save Me, Joe Louis 257 9 King of the Hill, and Further Raging Bulls 316 Conclusion 367 References 392 Select Bibliography 456 Acknowledgements 470 Photo Acknowledgements 471 Index 472 001_025_Boxing_Pre+Ch_1 25/1/08 15:37 Page 6 001_025_Boxing_Pre+Ch_1 25/1/08 15:37 Page 7 Introduction The symbolism of boxing does not allow for ambiguity; it is, as amateur mid- dleweight Albert Camus put it, ‘utterly Manichean’. -

THE CYBER BOXING ZONE Presents the Featherweight Champions

THE CYBER BOXING ZONE presents The Featherweight Champions The following list gives credit to "The Man Who Beat The Man." We are continually adding biographies and full records, so check back Comments can be sent to The Research Staff. Ciao! Torpedo Billy Murphy (1890-1891) Young Griffo (1891 moves up in weight) George Dixon (1891-1897) Solly Smith (1897-1898) Dave Sullivan (1898) George Dixon (1898-1900) Terry McGovern (1900-1901) Young Corbett II (1901-1902, vacates title) Abe Attell (1903-1912) Johnny Kilbane (1912-1923) Eugene Criqui (1923) Johnny Dundee (1923 through August 1924, gave up title) Louis "Kid" Kaplan (1925, resigned title Jul 1926) Tony Canzoneri(1928) Andre Routis (1928-1929) Bat Battalino (1929- Mar. 1932, relinquishes title) 1932-1937: title claimants include Tommy Paul, Kid Chocolate (resigned NBA title 1934), Freddie Miller, Baby Arizmendi, Mike Belloise, and Petey Sarron Henry Armstrong (1937-1938, vacates title) Joey Archibald (1939-1940) Harry Jeffra (1940-1941) Joey Archibald (1941) Albert "Chalky" Wright (1941-1942) Willie Pep (1942-1948) Joseph "Sandy" Saddler (1948-1949) Willie Pep (1949-1950) Joseph "Sandy" Saddler (1950-1957, retires 1/21/57) Hogan "Kid" Bassey (1957-1959) Davey Moore (1959-1963) Ultiminio "Sugar" Ramos (1963-1964) Vicente Saldivar (1964 retires October 14, 1967) Johnny Famechon (1969-1970) Vicente Saldivar (1970) Kuniaki Shibata (1970-1972) Clemente Sanchez (1972) Jose Legra (1972-1973) Eder Jofre [1973-1974, fizzles out] Alexis Arguello (1975-1977, -

Sam Langford Career Record: Click Alias: Boston Tar Baby Nationality

Name: Sam Langford Career Record: click Alias: Boston Tar Baby Nationality: Canadian Birthplace: Weymouth, Nova Scotia Born: 1883-03-04 Died: 1956-01-12 Age at Death: 72 Height: 5' 6� Reach: 72" Division: Heavyweight Manager: Joe Woodman He was a little man. He only Stood 5'6" yet he was known as "the giant killer." This fighter who beat the biggest and toughest of them all from lightweight to heavyweight. There was Joe Gans, Jack O'Brien, two World champions, and both went down under his blows. And yet the strange part of it is that this boxer, the hardest hitter in history never became a world's champion. And why? Because he was too good! This Is the story of Sam Langford, the Nova Scotia Tar Baby. Sam was born in Weymouth, a thriving lumber port In Southern Nova Scotia, on March 4th., 1886. During the American War of Independence, over 2000 negro slaves escaped from the plantations to join the British Army in New York City. And there they fought as soldiers in the battle of Harlem Heights. When the British evacuated New York by ship in 1783, they took negro soldiers along with them. Soon after, these negroes were settled in Nova Scotia in and around Halifax, Digby, Weymouth and Saint John. William Langford, Sam's great-grandfather, was among them. He was the son of a father, a short, stocky lumberjack who was recognized as the toughest and strongest log drawer an the Sissiboo River. Sam was one of many children in the Langford family who lived in an old shanty on the outskirts of Weymouth. -

Black Heavyweight Champions As Icons of Resistance A

“I HAD TO BEAT HIM FOR A CAUSE”: BLACK HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPIONS AS ICONS OF RESISTANCE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY AUGUST 2012 By Michael Newalu Thesis Committee: Marcus Daniel, Chairperson Njoroge Njoroge Suzanna Reiss Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Jack Johnson, The Great Black Hope ............................................................................ 8 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................. 39 Chapter 2: Joe Louis, Race Icon to National Hero ........................................................................ 43 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................. 72 Chapter 3: Muhammad Ali, Icon of Black Power ......................................................................... 76 Conclusion: Race Icons to Commodities ................................................................................ 104 Conclusion: Where Have the Heroes Gone? ............................................................................... 109 Bibliography ............................................................................................................................... -

The Boxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 7 – No 15 18Th Dec , 2011

1 The Boxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 7 – No 15 18th Dec , 2011 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to sign up for the newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] 2 Name: Young Stribling Career Record: click Alias: King of the Canebrakes Birth Name: William Lawrence Stribling Jr. Nationality: US American Birthplace: Bainbridge, GA, USA Hometown: Macon, GA Born: 1904-12-26 Died: 1933-10-03 Age at Death: 28 Stance: Orthodox Height: 6′ 1″ Reach: 188 Trainer: Ma Stribling Manager: William L. (Pa) Stribling, Sr. Elder brother of fellow boxer Herbert (Baby) Stribling According to the Nov. 7, 1927 Spokane Spokesman Review newspaper, just prior to Stribling's visit to nearby Dishman, WA: This was not Stribling's first visit to the Spokane area. In 1911, he, Ma, Pa, and brother Graham had come to Spokane on the Sullivan and Considine Vaudeville Circuit with an acrobatic act called the "Four Novelty Grahams." They spent one week at the Empress Theater, then called the Washington Theater. As part of the show, the Stribling brothers boxed exhibitions. Stribling was one of the best high school basketball players in the United States. He was known as a "dead shot" (a very accurate shooter). His team went to the national interscholastic tournament at Chicago, but he was ruled ineligible to play because of his professional boxing. He was also quite talented at golf, hunting, fishing, speedboat racing and tennis. Stribling was also an avid and accomplished aviator who loved to fly. He died October 3, 1933, after a motorcycle/automobile accident when he was just 28.