An Introduction of Carl Vine's Three Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January February March 2014

This Edition Join our Birthday celebration Experience three Great Performers Madeleine Peyroux covers Ray Charles MusicPlay Children’s Festival January February March 2014 PP320258/0121 MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY Bear with Me – p5 Wishhh! – p5 Nests – p5 Hansel & Gretel and Magic Piano & Peter & the Wolf – p4 The Tale of Peter The Chopin Shorts Whack, bang, crash! Rabbit – p4 p4 Paint What You Hear p5 p5 Workshops Workshops – p5 JANUARY Workshops – p5 16 p5 17 18 19 20 21 22 25 26 27 29 01 02 Til the Black Melbourne Albare: Lady Sings Recital Centre’s The Road Ahead p6 5th Birthday p6 Celebration p20–21 FEBRUARY 03 04 05 08 09 Myth of the Cave If On a Winter’s London Klezmer Mostly Mozart: Alchemy Alchemy p6 Night a Traveler Quartet The Masters p9 p9 p8 p8 p9 Daniel Hope Landscapes – p7 External & Internal 10 11 12 p9 13 14 15 ACO VirtUal ACO VirtUal ACO VirtUal ACO VirtUal ACO VirtUal p10 p10 p10 p10 p10 Kid Creole & Bach Magnificat Bach Magnificat the Coconuts p12 p12 p11 18 19 20 21 22 23 Ólafur Arnalds Kelemen Quartet Timo-Veikko Valve Top Class Music St David’s Day Música Española Mozart’s p13 p14 p15 Performance & Concert p16 Last Concerto Massimo Scattolin Investigation – p15 p16 Kelemen Quartet p17 p14 Festival of Beautiful p14 Sound 24 25 26 p15 27 28 01 02 Rebuild The Fire of Love An English Fancie To Sleep To Dream To Sleep To Dream To Sleep To Dream p17 p18 p18 p22 p22 p22 Madeleine Peyroux – Madeleine Peyroux – Balanescu Quartet To Russia With Love The Blue Room The Blue Room ‘Maria T’ p24 MARCH -

Programme Cover 21.03.2021

Our Sponsors... TEAM National Trust membership offers free entry to hundreds of Trust properties throughout Australia and overseas and helps secure the future of our natural and built heritage – phone 03 9656 9800 OF PIANISTS COLIN & CICELY RIGG BEQUEST, ADMINISTERED BY EQUITY TRUSTEES www.teamofpianists.com.au BRILLIANT AUSTRALIAN BERNIES MUSIC LAND & AND INTERNATIONAL PERFORMERS THE TEAM OF PIANISTS - IN HERITAGE SETTINGS A GREAT ASSOCIATION Recognised for consistent presentation of top-class performances, the Team of In 1988, Bernie Capicchiano invited me to adjudicate the first Bernstein Pianists is supported by enthusiastic audiences, who treasure the privilege of Competition. I was very impressed with the sounds of the Bernstein piano, and experiencing excellent performances at close range, often in heritage venues. soon after that, the Team of Pianists obtained Bernstein pianos for its concerts. Subsequently, the Team performed regularly on radio 3MBS-FM in a The Team and their artists bring audiences into contact with great music, programme called 'The Bernstein Piano Hour' and later, we made CDs at MOVE providing a vital sense of connection with the past. Fine solo and chamber Records, using Bernstein pianos from Bernies Music Land. These CDs have been very successful and continue to be available commercially. works, chosen specially with particular venues and Following the first Bernstein Competition, Bernie introduced masterclasses performers in mind, form and teachers’ seminars and with great support from his family, he encouraged the basis of the Team’s music in the community. Bernie and I became close friends, both of us having programmes, exciting similar aims in lifting the standards of piano playing and in promoting music listeners' emotions and generally. -

Participating Artists

The Flowers of War – Participating Artists Christopher Latham and in 2017 he was appointed Artist in Ibrahim Karaisli Artistic Director, The Flowers of War Residence at the Australian War Memorial, Muezzin – Re-Sounding Gallipoli project the first musician to be appointed to that Ibrahim Karaisli is head of Amity College’s role. Religion and Values department. Author, arranger, composer, conductor, violinist, Christopher Latham has performed Alexander Knight his whole life: as a solo boy treble in Musicians Baritone – Re-Sounding Gallipoli St Johns Cathedral, Brisbane, then a Now a graduate of the Sydney decade of studies in the US which led to Singers Conservatorium of Music, Alexander was touring as a violinist with the Australian awarded the 2016 German-Australian Chamber Orchestra from 1992 to 1998, Andrew Goodwin Opera Grant in August 2015, and and subsequently as an active chamber Tenor – Sacrifice; Race Against Time CD; subsequently won a year-long contract with musician. He worked as a noted editor with The Healers; Songs of the Great War; the Hessisches Staatstheater in Wiesbaden, Australia’s best composers for Boosey and Diggers’ Requiem Germany. He has performed with many of Hawkes, and worked as Artistic Director Born in Sydney, Andrew Goodwin studied Australia’s premier ensembles, including for the Four Winds Festival (Bermagui voice at the St. Petersburg Conservatory the Sydney Philharmonia Choirs, the Sydney 2004-2008), the Australian Festival of and in the UK. He has appeared with Chamber Choir, the Adelaide Chamber Chamber Music (Townsville 2005-2006), orchestras, opera companies and choral Singers and The Song Company. the Canberra International Music Festival societies in Europe, the UK, Asia and (CIMF 2009-2014) and the Village Building Australia, including the Bolshoi Opera, La Simon Lobelson Company’s Voices in the Forest (Canberra, Scala Milan and Opera Australia. -

Omega-2018-Seasonbrochure-Web.Pdf

1 Welcome Moving into our thirteenth season, Omega Ensemble has come of age and entered its teens! If childhood is about magic, the 2018 Concert Season introduces mystery, love, romance and passion. We are proud to continue to perform our Virtuoso Series in the stunning City Recital Hall, alongside our Master Series at the iconic Sydney Opera House. Our 2018 Season is all about relationships, intimacy and connections, between our artists, our audience and the music itself. David Rowden Maria Raspopova Founder and Co-Artistic Director Co-Artistic Director 2 Season Calendar Concert Date and Time Venue Pg O Miss Brill - An Australian Premiere Sun 18 Feb, 7:00pm Art Gallery of New South Wales 21 M Summer Winds: From Beethoven to Ravel Sun 25 Feb, 2:30pm Utzon Room, Sydney Opera House 15 O Four Winds Festival Fri 30 Mar, 5:00pm Bermagui, NSW 21 V Eternal Quartets: Messiaen and Schubert Wed 11 Apr, 7:30pm City Recital Hall 7 O Annual Fundraising Gala Wed 23 May, 7:00pm University Union and Schools Club 21 M Fairy Tales: Schumann, Bruch and Borodin Sun 17 Jun, 2:30pm Utzon Room, Sydney Opera House 16 V Love: Weber and Franck Wed 18 July, 7:30pm City Recital Hall 8 V Joy: Farrenc and Beethoven Tue 25 Sept, 7:30pm City Recital Hall 11 M Vocalise: Rachmaninoff and Poulenc Sun 21 Oct, 2:30pm Utzon Room, Sydney Opera House 17 V Momentum: Schubert and Mendelssohn Tues 13 Nov, 7:30pm City Recital Hall 12 M Maria Raspopova in Recital Sun 2 Dec, 2:30pm Utzon Room, Sydney Opera House 18 M = Master Series V = Virtuoso Series O = Other Performance Composer -

Elena Kats-Chernin

Elena Kats-Chernin Elena Kats-Chernin photo © Bruria Hammer OPERAS 1 OPERAS 1 OPERAS Die Krönung der Poppea (L'incoronazione di Poppea) Der herzlose Riese Claudio Monteverdi, arranged by Elena Kats-Chernin The Heartless Giant 1643/2012/17 3 hr 2020 55 min Opera musicale in three acts with a prologue 7 vocal soloists-children's choir- 1.1.1.1-1.1.1.1-perc(2)-3.3.3.3.2 4S,M,A,4T,2Bar,B; chorus; 0.2.0.asax.tsax(=barsax).0-0.2.cimbasso.0-perc(2):maracas/cast/claves/shaker/guiro/cr ot/tgl/cyms/BD/SD/tpl.bl/glsp/vib/wdbls/congas/bongos/cowbell-continuo-strings; Tutti stings divided in: vla I–III, vlc I–II, db; Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Continuo: 2 gtr players, doubling and dividing the following instruments: banjo, dobro, mandolin, 12-string, electric, classical, Jazz, steal-string, slide, Hawaii, ukulele (some Iphis effects may be produced by the 1997/2005 1 hr 10 min same instrument); 1 vlc(separate from the celli tutti); 1theorbo; 1kbd synthesizer: most used sounds include elec.org, Jazz.org, pipe.org, chamber.org, hpd, clavecin, and ad Opera for six singers and nine musicians lib keyboard instruments as available. 2S,M,2T,Bar 1(=picc).0.1(=bcl).0-1.0.0.0-perc(1):wdbl/cyms/hi hat/xyl/marimba/SD/ World premiere of version: 16 Sep 2012 vib or glsp/3cowbells/crot/BD/tpl.bl/wind chimes/chinese bl/claves- Komische Oper, Berlin, Germany pft(=kbd)-vln.vla.vlc.db Barrie Kosky, director; Orchester und Ensemble der Komischen Oper Berlin Conductor: André de Ridder World Premiere: 03 Dec 1997 Bangarra Dance -

Beethoven's Eroica

BEETHOVEN’S EROICA 10–12 MAY 2018 CONCERT PROGRAM Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis conductor Moye Chen piano Vine Concerto for Orchestra – Composer in Residence Liszt Piano Concerto No.1 INTERVAL Beethoven Symphony No.3 Eroica Running time: 2 hours, including a 20-minute interval In consideration of your fellow patrons, the MSO thanks you for silencing and dimming the light on your phone. The MSO acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which we are performing. We pay our respects to their Elders, past and present, and the Elders from mso.com.au other communities who may be in attendance. (03) 9929 9600 2 MELBOURNE SYMPHONY SIR ANDREW DAVIS ORCHESTRA CONDUCTOR Established in 1906, the Melbourne Chief Conductor of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra (MSO) is an Symphony Orchestra, Sir Andrew arts leader and Australia’s longest- Davis is also Music Director and running professional orchestra. Chief Principal Conductor of the Lyric Opera Conductor Sir Andrew Davis has of Chicago. He is Conductor Laureate been at the helm of MSO since 2013. of both the BBC Symphony Orchestra Engaging more than 4 million people and the Toronto Symphony, where he each year, the MSO reaches a variety has also been named interim Artistic of audiences through live performances, Director until 2020. recordings, TV and radio broadcasts In a career spanning more than 40 and live streaming. years he has conducted virtually all The MSO also works with Associate the world’s major orchestras and opera Conductor Benjamin Northey and companies, and at the major festivals. Cybec Assistant Conductor Tianyi Lu, Recent highlights have included as well as with such eminent recent Die Walküre in a new production guest conductors as Tan Dun, John at Chicago Lyric. -

14Th Annual Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address 2012

australian societa y fo r s music educationm e What Would Peggy Do? i ncorporated 14th Annual Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address 2012 Michael Kieran Harvey The New Music Network established the Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address in 1999 in honour of one of Australia’s great international composers. It is an annual forum for ideas relating to the creation and performance of Australian music. In the spirit of the great Australian composer Peggy Glanville-Hicks, an outstanding advocate of Australian music delivers the address each year, challenging the status quo and raising issues of importance in new music. In 2012, Michael Kieran Harvey was guest speaker presenting his Address entitled What Would Peggy Do? at the Sydney Conservatorium on 22 October and BMW Edge Fed Square in Melbourne on 2 November 2012. The transcripts are reproduced with permission by Michael Kieran Harvey and the New Music Network. http://www.newmusicnetwork.com.au/index.html Australian Journal of Music Education 2012:2,59-70 Just in case some of you are wondering about I did read an absolutely awe-inspiring Peggy what to expect from the original blurb for this Glanville-Hicks Address by Jon Rose however, address: the pie-graphs didn’t quite work out, and and I guess my views are known to the address powerpoint is so boring, don’t you agree? organisers, so, therefore, I will proceed, certain For reasons of a rare dysfunctional condition in the knowledge that I will offend many and I have called (quote) “industry allergy”, and for encourage, I hope, a valuable few. -

2019 Annual Report

MUSICA VIVA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 CONTENTS CHAIRMAN & CEO’S REPORT 4 COMPANY OVERVIEW 5 OUR REACH & IMPACT 6 A TRIBUTE TO CARL VINE AO 8 INSPIRING STUDENTS & TEACHERS Musica Viva In Schools 11 Musica Viva In Schools Program Reach 14 Don’t Stop The Music 15 Strike A Chord 15 SUPPORTING AUSTRALIAN CREATIVITY Masterclasses 17 FutureMakers 18 Australian Composers 20 Janette Hamilton Studio 21 PRESENTING THE FINEST MUSICIANS International Concert Season 23 Morning Concerts 26 Musica Viva Sessions 28 Musica Viva Festival 30 ENGAGING WITH REGIONAL AUDIENCES Regional Touring Program 33 Huntington Estate Music Festival 34 INDIVIDUAL GIVING, CORPORATE PARTNERSHIPS AND TRUSTS & FOUNDATIONS Individual Giving 37 Strategic Partnerships 40 Our Partners 42 Our Supporters 44 KEY FINANCIALS, ACTIVITY & REACH 50 GOVERNANCE 55 STAFF & VOLUNTEERS 59 Choir of King’s College, Cambridge performing in Adelaide Cover: Tessa Lark, Musica Viva Festival | Matthias Schack-Arnott, FutureMakers | student participant, Musica Viva In Schools 2 MUSICA VIVA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 MUSICA VIVA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 3 CHAIRMAN & CEO’S REPORT COMPANY OVERVIEW We are pleased to present another year of results that TO MAKE AUSTRALIA A MORE MUSICAL PLACE demonstrate Musica Viva Australia’s reach, artistic vibrancy and institutional stability. PURPOSE TO CREATE A NATIONAL CULTURE BASED ON CREATIVITY AND As an organisation founded by musicians, we recognise that without artists we would not exist or be able to achieve the impact IMAGINATION WHICH VALUES THE QUALITY, we desire. This year, Musica Viva employed 352 artists – 80% VISION DIVERSITY, CHALLENGE AND JOY OF LIVE CHAMBER MUSIC of whom were Australian. On concert stages (both regional and metro), in schools and online, Musica Viva brought music and TO ENRICH COMMUNITIES ACROSS AUSTRALIA BY music education of exceptional quality to 358,502 Australians. -

Impact Report 2019 Impact Report

2019 Impact Report 2019 Impact Report 1 Sydney Symphony Orchestra 2019 Impact Report “ Simone Young and the Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s outstanding interpretation captured its distinctive structure and imaginative folkloric atmosphere. The sumptuous string sonorities, evocative woodwind calls and polished brass chords highlighted the young Mahler’s distinctive orchestral sound-world.” The Australian, December 2019 Mahler’s Das klagende Lied with (L–R) Brett Weymark, Simone Young, Andrew Collis, Steve Davislim, Eleanor Lyons and Michaela Schuster. (Sydney Opera House, December 2019) Photo: Jay Patel Sydney Symphony Orchestra 2019 Impact Report Table of Contents 2019 at a Glance 06 Critical Acclaim 08 Chair’s Report 10 CEO’s Report 12 2019 Artistic Highlights 14 The Orchestra 18 Farewelling David Robertson 20 Welcome, Simone Young 22 50 Fanfares 24 Sydney Symphony Orchestra Fellowship 28 Building Audiences for Orchestral Music 30 Serving Our State 34 Acknowledging Your Support 38 Business Performance 40 2019 Annual Fund Donors 42 Sponsor Salute 46 Sydney Symphony Under the Stars. (Parramatta Park, January 2019) Photo: Victor Frankowski 4 5 Sydney Symphony Orchestra 2019 Impact Report 2019 at a Glance 146 Schools participated in Sydney Symphony Orchestra education programs 33,000 Students and Teachers 19,700 engaged in Sydney Symphony Students 234 Orchestra education programs attended Sydney Symphony $19.5 performances Orchestra concerts 64% in Australia of revenue Million self-generated in box office revenue 3,100 Hours of livestream concerts -

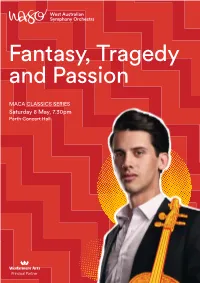

2021 Fantasy, Tragedy and Passion

MACA CLASSICS SERIES Saturday 8 May, 7.30pm Perth Concert Hall C3_A5_Program Cover.indd 1 26/3/21 7:50 am MACA HAS BEEN PARTNERING WITH WEST AUSTRALIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SINCE 2014 We are excited to continue our support towards their mission to touch souls and enrich lives through music. Over the last 10 years MACA has raised more than $12 million for various charity and community groups in support of the performing arts, cancer research, medical care, mental health and Aboriginal youth in remote communities across Western Australia. We pride ourselves on being a leader in the community supporting a wide range of initiatives. MACA is an integrated services contractor specialising in: • Mining • Crushing • Civil Construction • Infrastructure • Mineral Processing Equipment www.maca.net.au West Australian Symphony Orchestra respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners, Custodians and Elders of the Indigenous Nations across Western Australia and on whose Lands we work. MACA CLASSICS SERIES Fantasy, Tragedy and Passion Carl VINE V (5 mins) Felix MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E minor (27 mins) Allegro molto appassionato – Andante – Allegro non troppo – Allegro molto vivace Interval (25 mins) Georges BIZET Carmen: Suite No.1 (12 mins) Prélude Aragonaise Intermezzo Les dragons d’Alcala Les Toréadors Pyotr Ilyich TCHAIKOVSKY Romeo and Juliet – Fantasy Overture (21 mins) Thaddeus Huang conductor Harry Bennetts violin Wesfarmers Arts Pre-concert Talk Find out more about the music in the concert with this week’s speaker, Jen Winley (see page 22 for her biography). The Pre-concert Talk will take place at 6.45pm in the Terrace Level Foyer. Wesfarmers Arts Meet the Artists Join tonight’s conductor, Thaddeus Huang and soloist, Harry Bennetts for a post-concert interview. -

Cello Dreaming Programme Notes 27 Sept 2015

CELLO DREAMING CoralCoral Lancaster Lancaster Alan MacLean cellocello piano Cello Dreaming Concert A programme that explores aspects of dreaming, and the myriad ways in which music reveals to us inner realities of life Coral Lancaster and Alan MacLean 27 September 2015, 4pm Holywell Music Room Coral Lancaster pursues a varied career as a freelance chamber musician, orchestral musician, and teacher. Originally from Perth, Western Australia, Coral studied with Gregory Baron, Suzanne Wijsman, and David Pereira (dedicatee of Inner World and Threnody), before moving to the UK in 1997. Based in Oxford, Coral performs with the Lyric Piano Trio and the Jubilee Ensemble, and teaches locally. She is known for her sensitive performances, and also works regularly with the Philharmonia, the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. This year Coral has toured with the Philharmonia to Madrid and Paris, and will shortly be travelling to Iceland with them as well. She can next be heard in Oxford performing in a solo lunchtime concert at St Michael at the North Gate, on 23rd November. Alan MacLean is a graduate of The Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama. Alan studied with the Hungarian pianist Bela Simandi and received the award for the most outstanding student in his final year. Further study followed with internationally renowned pianists including Karl Ulrich Schnabel. Much in demand as a chamber musician, he has played with many of the country's leading instrumentalists and he premiered Malcolm Arnold's ‘Trio Bourgeoises’ and a recent arrangement of John Field's Rondo in A flat for Piano and Orchestra. -

A Study of the Third Piano Sonata of Carl Vine (2007)

A STUDY OF THE THIRD PIANO SONATA OF CARL VINE (2007): THE MUSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE THIRD SONATA COMPARED THROUGH THE FIRST SONATA AND SECOND SONATA AND PRACTICAL PERFORMANCE GUIDANCE D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Music Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gina Kyounglae Kang, B.M., M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2012 Document Committee: Dr. Caroline Hong, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Prof. Paul Robinson ABSTRACT The majority of performers think contemporary music is tedious, complicated, and difficult to play and understand because music without clear tonality or following in the romantic or popular style is often very difficult to comprehend or to enjoy. Many musicians veer away from wanting to play music that is not tonal, or that does not offer immediate enjoyment during performance (e.g. tonal lyricism, singable melodies, understandable chordal progressions, ease of playing idiomatic passages familiar to the classically trained pianist) etc. Therefore, the music of contemporary living composers is often not played enough, not advocated. As I learned and performed Carl Vine’s third sonata for DMA recital, there were barely any references to his work. However, despite the scarcity of references, the sonata may be recognizable to performers through listening, comparing, and contrasting the style of all three sonatas of Carl Vine, and analyzing the work. Also, creating practical practice methods helps the technique required to execute this sonata with ease and fluidity. Therefore, I feel contemporary music does not seem so difficult anymore.