Anna Stegh Camati Uniandrade, Paraná

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DUNCAN SYKRS Artistic Dircctor VINCENT EAVIS

George Vbollands and Margarct llcn<llt' li rurrrlt'< l Pl rst t'rrirrrrr irr 1924.'lhe company's first procluctiorr r,r,:rs llrt' rrou littl( krr()\\'n Tbe Tide by Basil McDonalcl llitstitrgs. Sirtt'r' tlrt'rr. llrt' r'r)nrl);urv has performed nearly 250 plays, usitrg llltt-r-rllv:rs;r lr:rsc srrtt' 1945. In this time Prosceniuln hits built ul) l sln)ns r1'l)lrt.ltr()rr for performing challenging plays (both clrtssic lrrrl cr)nl('nrl)()r.:u-\ ) to a high stanclard. Chairmztn DUNCAN SYKRS Artistic Dircctor VINCENT EAVIS Secretary ROBERT EWEN Contact uri 1rt: www.pfoscenirun. () rg - r r l( 'l'his seasr)n sLrpl)()r'l t'<l llr Rcgistercrl clr:rrit1, - Nr r Molly Sweeney By Brian Friel o tr o o U'= ->I o E = 25th-28h January 2006 Travellers Studio, Hatch End Molly Sweeney by Brian Friel The Playwright Molly Angie Sutherland Born in Omagh, Co. Tyrone in 1929, Brian Friel and his family moved to Derry Frank Duncan Sykes City in 1939. He started to write in the 1950s, first short stories and then Mr Rice David Pearson experimenting with drama. He recalled some twenty years later the impulse /o survey and analyse the mixed holding I had inherited: the personal, traditional Directed by Crystal Anthony and acquired lvtowledge that cocooned me, an lrish Catholic teacher with a Stage Manager Colin Hickman nationalist background, living in a schizophrenic community, son of a teacher, Lighting/Sound Arts Culture Harrow grandson of peasants who could neither read or write. -

Female Identity in Brian Friel's Molly Sweeney

34 / JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE LITERATURE AND AESTHETICS From Sight to Touch: Female Identity in Brian Friel’s Molly Sweeney HAWK CHANG Abstract emale characters are often foils in Brian Friel’s plays. However, Friel’s Molly Sweeney F(1994) focuses on women’s central problem—the question of female identity. Although much has been examined regarding national identity, history, religion, emigration, and translation in Friel’s works, issues relevant to women and female identity are less addressed. This paper discusses female identity and difference in Friel’s Molly Sweeney via French feminist theories, exploring the extent to which women can move towards a position outside and beyond the male logocentric logic of A and B, a position of otherness or difference. Keywords: Irish women, identity, difference, Brian Friel, Molly Sweeney I. Prelude Although Irish women have been characterized in terms of allegorical mother figures for some time (Innes 1993, pp. 40-41; Nash 1993, p. 47), the image of women and their actual lives began to undergo significant changes in the last few decades of the twentieth century. Eavan Boland’s poem “The Women” showcases the way contemporary Irish women better grasp their own identity by removing “woman” from a clear-cut hierarchical dichotomy of man and woman and placing her in the nebulous state of “the in-between” (2005, p. 141). Nonetheless, there are still women who fail to recognize their innate power of feminine identity as difference lapses into an unfathomable darkness, as presented in Friel’s Molly in Molly Sweeney. Friel gained wide recognition with his earlier play Philadelphia, Here I Come (1964) and has since written “the most substantial and impressive body of work in contemporary Irish drama” (Maxwell 1984, p. -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66686-2 - The Cambridge Companion to Brian Friel Edited by Anthony Roche Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Brian Friel Brian Friel is widely recognized as Ireland’s greatest living playwright, win- ning an international reputation through such acclaimed works as Transla- tions (1980) and Dancing at Lughnasa (1990). This collection of specially commissioned essays includes contributions from leading commentators on Friel’s work (including two fellow playwrights) and explores the entire range of his career from his 1964 breakthrough with Philadelphia, Here I Come! to his most recent success in Dublin and London with The Home Place (2005). The essays approach Friel’s plays both as literary texts and as performed drama, and provide the perfect introduction for students of both English and Theatre Studies, as well as theatregoers. The collection considers Friel’s lesser-known works alongside his more celebrated plays and provides a comprehensive crit- ical survey of his career. This is the most up-to-date study of Friel’s work to be published, and includes a chronology and further reading suggestions. anthony roche is Senior Lecturer in English and Drama at University College Dublin. He is the author of Contemporary Irish Drama: From Beckett to McGuinness (1994). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66686-2 - The Cambridge Companion to Brian Friel Edited by Anthony Roche Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO BRIAN FRIEL -

Brian Friel in Spain: an Off-Centre Love Story

Estudios Irlandeses, Issue 16, 2021, pp. 110-124 https://doi.org/10.24162/EI2021-10076 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ AEDEI Brian Friel in Spain: An Off-Centre Love Story María Gaviña-Costero Universitat de València Copyright (c) 2021 by María Gaviña-Costero. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged for access. Abstract. Spanish theatres are not prolific in the staging of Irish playwrights. However, the Northern Irish writer Brian Friel (1929-2015) has been a curious exception, his plays having been performed in different cities in Spain since William Layton produced Amantes: vencedores y vencidos (Lovers: Winners and Losers) in 1972. The origin of Friel’s popularity in this country may be attributed to what many theatre directors and audiences considered to be a parallel political situation between post-colonial Ireland and the historical peripheral communities with a language other than Spanish: Catalonia, the Basque Country and Galicia; the fact is that the number of Catalan directors who have staged works by Friel exceeds that of any other territory in Spain. However, despite the political identification that can be behind the success of a play like Translations (1980), the staging of others with a subtler political overtone, such as Lovers (1967), Dancing at Lughnasa (1990), Molly Sweeney (1994), Faith Healer (1979) and Afterplay (2001), should prompt us to find the reason for this imbalance of representation elsewhere. By analysing the production of the plays, both through the study of their programmes and interviews with their protagonists, and by scrutinising their reception, I have attempted to discern some common factors to account for the selection of Friel's dramatic texts. -

Dancing at Lughnasa, Dublin and New York

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Dancing on a one-way street: Irish reactions to Dancing at Lughnasa in New York Author(s) Lonergan, Patrick Publication Date 2009 Lonergan, Patrick. (2009). Dancing on a One-Way Street: Irish Publication Reactions to Dancing at Lughnasa in New York In John P. Information Harrington (Ed.), Irish theater in America : essays on Irish theatrical diaspora New York: Syracuse University Press. Publisher Syracuse University Press Link to publisher's http://www.syracuseuniversitypress.syr.edu/ version Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/6789 Downloaded 2021-09-27T12:30:41Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. 1 Dancing on a One-Way Street: Irish Reactions to Dancing at Lughnasa in New York Brian Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa is an important example of the inter-relationship of American and Irish theatre, particularly since 1990. Its script draws heavily on American culture, bringing us songs by Cole Porter and an approach to the narration of remembered events that is highly reminiscent of the work of Tennessee Williams. And its production was one of the first of many Irish successes on the New York stage from the 1990s onwards, being followed by productions of plays by Martin McDonagh, Conor McPherson and indeed by Brian Friel himself, whose Faith Healer was a critical and commercial success on Broadway in 2006. Dancing at Lughnasa premiered on 24 April 1990 at the Abbey Theatre, where it was directed by Patrick Mason. -

Instead of an Obituary. Brian Friel's Silent Voices. Memory And

Studi irlandesi. A Journal of Irish Studies, n. 6 (2016), pp. 11-16 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13128/SIJIS-2239-3978-18452 Instead of an Obituary. Brian Friel’s Silent Voices. Memory and Celebration Giovanna Tallone Independent scholar (<[email protected]>) On the occasion of Brian Friel’s eightieth birthday in 2009, Seamus Heaney published a slender volume called Spelling It Out, whose aim was to honour and celebrate the playwright and to mark a long-standing friendship. Taking the letters of Friel’s name and surname in a game with words and language, Heaney created a sort of microcosm of Friel’s world. Starting with B, for Ballybeg, “the invented domain where so many of Brian’s plays are set, the hub of his imagined world” (Heaney 2009, [3]), the poet moves on to I “for in- tegrity”, but also for “Ireland” and for “intimacy”, thus mixing the public and the personal, “the inner self, the mysterious source and living of being” ([5]). At the same time this is a reminder of the stage directions in Philadelphia, Here I Come! (1964), where Gar O’Donnell is split between Public Gar and Private Gar, the latter being “the unseen man, the man within, the alter ego, the se- cret thoughts, the id” (Friel 1984, 27). Words like “no”, “fiction”, “experiment”, “love” and “language” are likewise entered in what Heaney defines “not so much an abecedary as a befrielery” ([1]), in an interplay of public and private levels. The death of Brian Friel on October nd2 2015 followed Heaney’s death about two years earlier, which meant the loss of two of the deepest, most eminent and most provocative voices in Irish literature and culture, whose echoes resound in the second half of the twentieth century and into the twen- ty-first. -

Translations

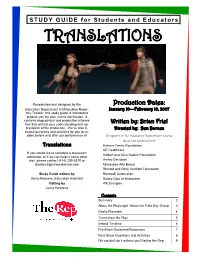

STUDY GUIDE for Students and Educators TRANSLATIONS Researched and designed by the Production Dates: Education Department at Milwaukee Reper- January 10—February 10, 2007 tory Theater, this study guide is intended to prepare you for your visit to the theater. It contains biographical and production informa- tion that will aid your understanding and ap- Written by: Brian Friel preciation of the production. We’ve also in- Directed by: Ben Barnes cluded questions and activities for you to ex- plore before and after our performance of Programs in the Education Department receive generous funding from: Translations Einhorn Family Foundation GE Healthcare If you would like to schedule a classroom Halbert and Alice Kadish Foundation workshop, or if we can help in some other way, please contact (414) 290-5370 or Harley Davidson [email protected] Milwaukee Arts Board Richard and Ethel Herzfeld Foundation Study Guide written by Rockwell Automation Dena Roncone, Education Assistant Rotary Club of Milwaukee Editing by WE Energies Jenny Kostreva Contents Summary 2 About the Playwright /About the Field Day Group 3 Gaelic Proverbs 4 Terms from the Play 5 Ireland Timeline 6 Pre-Show Questions/Resources 7 Post-Show Questions and Activities 8 We couldn’t do it without you/Visiting the Rep 9 1 Summary Translations takes place in a hedge-school in the Book. Yolland keeps getting distracted from his work townland of Baile Beag/Ballybeg, an Irish-speaking and discusses the beauty of the country, the language community in County Donegal. and the people. Yolland wants to learn Gaelic and con- templates living in Ireland. -

ABSTRACT a Director's Approach to Dancing at Lughnasa Heidi

ABSTRACT A Director’s Approach to Dancing at Lughnasa Heidi Breeden, M.F.A. Mentor: Marion Castleberry, Ph.D. This thesis details the production process for Baylor Theatre’s mainstage production of Dancing at Lughnasa by Brian Friel, directed by Heidi Breeden, in partial fulfillment of the Master of Fine Arts in Directing. Dancing at Lughnasa is a somewhat autobiographical memory play, featuring strong roles for women and requiring advanced acting skills. This thesis first investigates the life and works of Brian Friel, then offers a director’s analysis of the text, documents the director’s process for the production, and finally offers a reflection on the strengths and opportunities for improvement for the director’s future work. A Director's Approach to Dancing at Lughnasa by Heidi Breeden, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of Theatre Arts Stan C. Denman, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee Marion D. Castleberry, Ph.D., Chairperson DeAnna M. Toten Beard, M.F.A., Ph.D. David J. Jortner, Ph.D. Richard R. Russell, Ph.D. Accepted by the Graduate School May 2017 J. Larry Lyon, Ph.D., Dean Page bearing signatures is kept on file in the Graduate School. Copyright © 2017 by Heidi Breeden All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................... -

Postdramatic Features in Brian Friel's Molly

Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies E-ISSN: 2175-8026 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Brasil Stegh Camati, Anna LANDSCAPES OF THE MIND: POSTDRAMATIC FEATURES IN BRIAN FRIEL’S MOLLY SWEENEY Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, núm. 58, enero-junio, 2010, pp. 113-133 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=478348696006 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Landscapes of the Mind: Postdramatic... 113 LANDSCAPES OF THE MIND: POSTDRAMATIC FEATURES IN BRIAN FRIEL’S MOLLY SWEENEY Anna Stegh Camati Uniandrade, Paraná Learning to see is not like learning a new language. It’s like learning language for the first time. Denis Diderot Abstract: The contemporary debate regarding the new languages of the stage has developed into multiple directions. In Molly Sweeney (1994), Brian Friel rejects dramatic progression and interpersonal dialogue to privilege direct interaction with the audience that intensifies the production of presence. He combines conventional and postdramatic features in his presentation of alternating monologues by three speakers – Molly, Frank and Mr. Rice – whose solo voices create an allegory on the unwillingness of communication in our time. The emerging landscapes of the mind force the audience to deal with the indeterminacy of meaning, extending representation beyond dramatic action in the theatre. -

Redalyc.BRIAN FRIEL: the MASTER PLAYWRIGHT

Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies E-ISSN: 2175-8026 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Brasil Pelletier, Martine BRIAN FRIEL: THE MASTER PLAYWRIGHT Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, núm. 58, enero-junio, 2010, pp. 135-156 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=478348696007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Brian Friel: the master playwright 135 BRIAN FRIEL: THE MASTER PLAYWRIGHT Martine Pelletier University of Tours, France Abstract: Brian Friel has long been recognized as Ireland’s leading playwright. His work for the theatre spans almost fifty years and his reputation has expanded well beyond Ireland. In January 2009 Friel turned eighty and only a few months before, his adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, opened at the Gate Theatre Dublin on 30th September 2008. This article will first provide a survey of Brian Friel’s remarkable career, trying to assess his overall contribution to Irish theatre, before looking at his various adaptations to finally focus on Hedda Gabler, its place and relevance in the author’s canon. Keywordsds: Brian Friel, Irish Theatre, Hedda Gabler, Adaptation, Ireland. Brian Friel has long been recognized as the leading playwright in contemporary Ireland. His work for the theatre spans almost fifty years and his reputation has expanded beyond Ireland and outside the English-speaking world, where several of his plays are regularly produced, studied and enjoyed by a wide range of audiences and critics. -

Read the Performance Program Here!

IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE CHARLOTTE MOORE, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR | CIARÁN O’REILLY, PRODUCING DIRECTOR A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN MOLLY SWEENEY BY BRIAN FRIEL DIRECTED BY CHARLOTTE MOORE WITH GERALDINE HUGHES, PAUL O’BRIEN AND CIARÁN O’REILLY video editor sound designer post-production sound mix SARAH ZACHARY M. FLORIAN NICHOLS WILLIAMSON STAAB press representative general manager MATT ROSS LISA PUBLIC RELATIONS FANE TIME & PLACE Ballybeg, County Donegal, Ireland Running Time: 2 hours and 15 minutes including an intermission SPECIAL THANKS Irish Repertory Theatre would like to thank Geraldine Hughes, Paul O’Brien, the family of Brian Friel, Leah Schmidt of The Agency UK, The Keen Company, The Howard Gilman Foundation, Ciarán Madden - Consul General Of Ireland, and the Irish Abroad Unit of the Department of Foreign Affairs. THIS PRODUCTION IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH PUBLIC FUNDS FROM THE NEW YORK STATE COUNCIL ON THE ARTS, THE NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS, AXE-HOUGHTON FOUNDATION, AND OTHER PRIVATE FOUNDATIONS AND CORPORATIONS, AND WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE MANY GENEROUS MEMBERS OF IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE’S PATRON’S CIRCLE. WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST GERALDINE HUGHES (Molly of Being Ernest, Equus, Cymbeline, Sweeney) received the Los Democracy, King Lear (with Christopher Angeles Ovation, Garland Plummer), The Crucible (with Liam Neeson), and Drama Critics Circle Twelfth Night. Off-Broadway: Molly Sweeney Awards and a Drama League (Keen Company), The Mountains Look Award Nomination for Different, Is Life Worth Living? (Mint Theater), Outstanding Performance for her solo play Hamlet (NYSF), Death Defying Acts (Variety Belfast Blues, which she also wrote. Arts), Three Birds Alighting on a Field (MTC), Geraldine’s stage credits include: Harry Potter Widow’s Blind Date (Circle in the Square), And The Cursed Child, as Professor Moon for the Misbegotten (Pearl Theater). -

Playnotes-Lughnasa-1.Pdf

P L A Y N O T ES Y NO P LA Interviews &Commentary Background Information R e s o u R c e G u i d e season: 42 issue: 1 Discussion Programs The Artistic Perspective,For hosted byThe Artistic Director General Anita Stewart, is an Publicopportunity for audience members to delve deeper into the themes of the show through conversation with special guests. A different scholar, visiting artist, playwright, or other expert will join the discussion each time. The Artistic Perspective discussions are held after the first Sunday matinee performance. Page to Stage discussions are presented in partnership with the Portland Public Library. These discussions, led by Portland Stage artistic staff, actors, directors, and designers answer questions, share stories and explore the challenges of bringing a particular play to the stage. Page to Stage occurs at noon on the Tuesday after a show opens at the Portland Public Library’s Main Branch. Feel free to bring your lunch! Curtain Call discussions offer a rare opportunity for audience members to talk about the production with the performers. Through this forum, the audience and cast explore topics that range from the process of rehearsing and producing the text to character development to issues raised by the work. Curtain Call discussions are held after the second Sunday matinee performance. All discussions are free and open to the public. Show attendance is not required. To subscribe to a discussion series performance, please call the Box Office at 207.774.0465. Discussion Dates for Dancing at Lughnasa The Artistic Perspective: Sunday, Oct.