The Jewish Museum, New York City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KZ – Kampf – Kunst BORIS LURIE: NO!ART

KZ – Kampf – Kunst (CONCENTRATION CAMP – STRUGGLE – ART) BORIS LURIE: NO!ART The works of Boris Lurie have the power to shock. Many were created more than fifty years ago, but have lost none of their potential to rattle cages, to polarise opinion and to test the boundaries of tolerability. Boris Lurie’s comprehensive and controversial body of work will be presented in the NS Documentation Centre in Cologne as of 27 August 2014. The exhibition – developed in cooperation with the Boris Lurie Foundation in New York and under the curatorial direction of gallery owner Gertrude Stein – features the first impressive works created directly after Lurie’s release from Buchenwald concentration camp, as well as works from the 1940s and 1950s that have never been seen in Europe before. A selection of his impressive sculptural works from the 1970s will also be presented for the first time in the basement. The profoundly human existentialism and peculiarly European characteristics that inform his works – and, not least, his aggressively political outlook – made Lurie something of an outsider in a New York art world in thrall to abstract expressionism and pop art, a state of affairs that endured until his death in 2008. Born in Riga in 1924 to a wealthy Jewish middle-class family, the artist experienced the catastrophes and upheavals of the 20th century at first hand. Together with his father, he survived the Stutthof and Buchenwald concentration camps. His mother, grandmother, younger sister and childhood sweetheart were all murdered in the Massacre of Rumbula, near Riga, in 1941. Lurie described himself as a privileged concentration camp survivor who quickly gained a foothold as a translator in post-war Germany, emigrating to New York with his father in 1946, where he lived and worked for the rest of his days. -

Art Boris Lurie and NO!Art

1 Boris Lurie in NO!art Boris Lurie and NO!art Boris Lurie in NO!art Boris Lurie and NO!art Kazalo 4 Boris Lurie Andreja Hribernik 24 Uvod Introduction Ivonna Veiherte 26 Skrivna sestavina umetnosti – pogum 40 The Secret Component of Great Art – Courage Stanley Fisher (1960) 56 Izjava ob Vulgarni razstavi Vulgar Show Statement Boris Lurie (1961) 58 Izjava ob Vključujoči razstavi 59 Involvement Show Statement Stanley Fisher (1961) 62 Izjava ob razstavi Pogube Doom Show Statement Boris Lurie (1964) 66 Spremna beseda k razstavi kipov NO! Sama Goodmana 68 Introduction to Sam Goodman ‘NO-sculptures’ Thomas B. Hess (1964) 70 Spremna beseda k razstavi kipov NO! 71 Introduction to the NO-sculptures show Tom Wolfe (1964) 73 Kiparstvo (Galerija Gertrude Stein) 74 Sculpture (Gallery Gertrude Stein) Dore Ashton (1988) 76 Merde, Alors! 78 Merde, Alors! Harold Rosenberg (1974) 80 Bika za roge 81 Bull by the Horns Contents 84 Boris Lurie 107 Sam Goodman 122 Stanley Fisher 128 Aldo Tambellini 132 John Fischer 134 Dorothy Gillespie 138 Allan D’Arcangelo 142 Erró 148 Harriet Wood (Suzanne Long) 152 Isser Aronovici 154 Yayoi Kusama 158 Jean-Jacques Lebel 164 Rocco Armento 166 Wolf Vostell 172 Michelle Stuart Marko Košan 176 Pričevanje podobe (Lurie, Mušič, Borčić) 184 The Testimony of an Image (Lurie, Mušič, Borčić) 190 Seznam razstavljenih del List of exhibited works BORIS LURIE Portret moje matere pred ustrelitvijo / Portrait of My Mother Before Shooting, 1947, olje na platnu / Oil on canvas, 92,7 x 64,8 cm © Boris Lurie Art Foundation BORIS LURIE Tovorni vagon, asemblaž 1945 Adolfa Hitlerja / Flatcar. -

Boriss Lurje Un NO!Art Boris Lurie and NO!Art Boriss Lurje

Boriss Lurje un NO!art Boris Lurie and NO!art Boriss Lurje. Manai Šeinai Gitl/ manai Valentīnai. 1981. Papīrs, gleznojums, kolāža, 99x75 cm Boris Lurie. To my Sheina Gitl/ My Valentine. 1981. Paint, paper collage, tape on paper Boriss Lurje un NO!art Boris Lurie and NO!art Mākslas muzejs RīgAS BIRža Art Museum RIGA BOURSE 2019. gada 11. janvāris – 2019. gada 10. marts January 11, 2019 – March 10, 2019 Izstādes kuratore/ Curator of the exhibition: Ivonna Veiherte Projekta vadītāja/ Project manager: Vita Birzaka Izstādes dizains/ Design of the exhibition: Anna Heinrihsone Izstādes projekta sadarbības partneris/ Collaboration partner for the exhibition Boris Lurie Art Foundation, New York, USA: Gertrude Stein, President Anthony Williams, Chairman of the Board Chris Shultz, Collections Manager Jessica Wallen, Project Manager Rafael Vostell, Advisor Uz vāka: Boriss Lurje. Bez nosaukuma (Uzsmidzinātais NĒ). 1963. Masonīts, izsmidzināmā krāsa, 56x52 cm On the cover: Boris Lurie. Untitled (NO Sprayed). 1963. Spray paint on masonite © Boris Lurie Art Foundation Izstāde “Boriss Lurje un NO!art” turpina vienu no Mākslas muzejam RĪGAS BIRža tik svarīgajiem virzieniem – iepazīstināt skatītājus ar 20. gadsimta māks- las vēsturi, šajā gadījumā – ar tik spilgtu un neparastu kontrkultūras parādību kā NO!art kustība. Sociāli un politiski aktīvie sava ceļa gājēji, kā Boriss Lurje (Boris Lurie), Sems Gudmens (Sam Goodman), Stenlijs Fišers (Stanley Fisher), Ņujorkas kultūras dzīvē tiek atpazīti kā nepiekāpīgie opozicionāri, kuriem NO!art gars un 1960. gadu sākuma izstādes ir kļuvušas par impulsiem radošiem mek- lējumiem mūža garumā. Raksturojot šos māksliniekus un komentējot Borisa Lurje darbu izstādi savā galerijā, Ģertrūde Staina savulaik rakstījusi:” NĒ mākslā ir NĒ konformismam un materiālismam. -

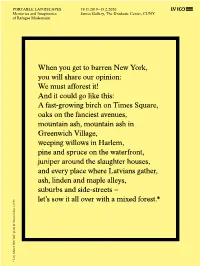

When You Get to Barren New York, You Will Share Our Opinion

PORTABLE LANDSCAPES 19.11.2019—15.2.2020 Memories and Imaginaries James Gallery, The Graduate Center, CUNY of Refugee Modernism When you get to barren New York, you will share our opinion: We must afforest it! And it could go like this: A fast-growing birch on Times Square, oaks on the fanciest avenues, mountain ash, mountain ash in Greenwich Village, weeping willows in Harlem, PORTABLE LANDSCAPES PORTABLE pine and spruce on the waterfront, juniper around the slaughter houses, and every place where Latvians gather, ash, linden and maple alleys, suburbs and side-streets – let’s sow it all over with a mixed forest.* * "Let's Afforest New York" poem by Gunars Saliņš. c. 1959. Saliņš. Gunars by poemYork" New * "Let's Afforest PORTABLE LANDSCAPES: Memories and Imaginaries of Refugee Modernism 19.11.2019—15.02.2020 James Gallery, The Graduate Center, CUNY Memories and Imaginaries Refugee of Modernism EXHIBITION CATALOGUE Artists: Editor: Daina Dagnija, Yonia Fain, Yevgeniy Fiks, Andra Silapētere Hell’s Kitchen collective, Rolands Kaņeps, Boris PORTABLE LANDSCAPES PORTABLE Lurie, Judy Blum Reddy, Karol Radziszewski, Design: Vladimir Svetlov & Aleksandr Zapoļ (Orbita Kārlis Krecers Group), Viktor Timofeev, Sigurds Vīdzirkste, Artūrs Virtmanis Texts: Katherine Carl, Solvita Krese, Inga Lāce, Andra Curators: Silapētere, Yevgeniy Fiks, Karol Radziszewski, Katherine Carl, Solvita Krese, Inga Lāce, Ksenia Nouril, Viktor Timofeev, Vladimir Svetlov Andra Silapētere & Aleksandr Zapoļ, Artūrs Virtmanis Exhibitions Coordinator: Language editing and proofreading: -

Exhibition Gazette (PDF)

ARTIST-RUN GALLERIES IN NEW YORK CITY Inventing 1952–1965 Downtown JANUARY 10–APRIL 1, 2017 Grey Gazette, Vol. 16, No. 1 · Winter 2017 · Grey Art Gallery New York University 100 Washington Square East, NYC InventingDT_Gazette_9_625x13_12_09_2016_UG.indd 1 12/13/16 2:15 PM Danny Lyon, 79 Park Place, from the series The Destruction of Lower Manhattan, 1967. Courtesy the photographer and Magnum Photos Aldo Tambellini, We Are the Primitives of a New Era, from the Manifesto series, c. 1961. JOIN THE CONVERSATION @NYUGrey InventingDowntown # Aldo Tambellini Archive, Salem, Massachusetts This issue of the Grey Gazette is funded by the Oded Halahmy Endowment for the Arts; the Boris Lurie Art Foundation; the Foundation for the Arts. Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Helen Frankenthaler Foundation; the Art Dealers Association Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965 is organized by the Grey Foundation; Ann Hatch; Arne and Milly Glimcher; The Cowles Art Gallery, New York University, and curated by Melissa Charitable Trust; and the Japan Foundation. The publication Rachleff. Its presentation is made possible in part by the is supported by a grant from Furthermore: a program of the generous support of the Terra Foundation for American Art; the J.M. Kaplan Fund. Additional support is provided by the Henry Luce Foundation; The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Grey Art Gallery’s Director’s Circle, Inter/National Council, and Visual Arts; the S. & J. Lurje Memorial Foundation; the National Friends; and the Abby Weed Grey Trust. GREY GAZETTE, VOL. 16, NO. 1, WINTER 2017 · PUBLISHED BY THE GREY ART GALLERY, NYU · 100 WASHINGTON SQUARE EAST, NYC 10003 · TEL. -

Boris Lurie Art Foundation, New York

BORIS LURIE NO!Art Бориса Лурье / NO!Art of Boris Lurie Июнь 2011 / June 2011 Выставка организована при поддержке Художественного Фонда Бориса Лурье, Нью-Йорк This exhibit is organized with the generous support of the Boris Lurie Art Foundation, New York Зверевский центр современного искусства благодарит за содействие нью-йоркских кураторов выставки Леонида Дрознера и Игоря Сатановского Zverev Center for Contemporary Art would like to thank Leonid Drozner and Igor Satanovsky (New York) Тексты: Дональд Каспит, Александр Соколов Дизайн каталога: Александр Соколов Фотографии работ предоставлены Фондом Бориса Лурье, Нью-Йорк Зверевский центр современного искусства, Москва, ул.Новорязанская, 29, Тел./Phone: +7 499 2656166 [email protected], www.zverevcenter.ru. Железнодорожный коллаж. 1959 Коллаж, бумага 38.1 x 54.6 см Railroad Collage. 1959 Collage on paper 38.1 x 54.6 cm Без названия. Без даты Бумага, холст, фольга, коллаж 44.5 x 78.7 см Untitled. No date Oil and paper collage on foil 44.5 x 78.7 cm Здесь в Нью-Йорке иначе Here in New York things are different чем в буковом лесочке...* than in the little beech grove...* Из стихотворения Бориса Лурье (1955) From a Boris Lurie poem, 1955 Текст: Александр Соколов by Alexander Sokolov Художник Борис Лурье, родившийся в Ленинграде в 1924-м Boris Lurie, regrettably, is practically unknown in Russia. The art- году,к сожалению, практически неизвестен в России. Он умер ist died in 2008 in New York, where he lived for 63 years and until в 2008 году в Нью-Йорке, где до недавних пор также не был recently was not in the public eye there either. -

01 Boris Lurie and NO!Art

154 MATTHIAS REICHELT 01 MATTHIAS REICHELT , “We have more or less said that we video interview with Boris Lurie, April 2002, 01 DVD III, 9:40 min. shit on everything” I also conducted short conversations with Gertrude Stein and Clayton Patterson. This Boris Lurie and NO!art material on eight sixty-minute MiniDVs (transferred to DVD) led to the idea for SHOAH and PIN-UPS: The NO!-Artist Boris Lurie, a documentary ✞lm by Reinhold Dettmer-Finke in collaboration with Matthias Reichelt, 88 min., Dolby Surround, ✞ de ✞- lmproduktion (Germany 2006). 155 “The origins of NO!art sprout from the Jewish experience, struck root in the world’s largest Jewish community in New York, a product of armies, concen- tration camps, Lumpenproletariat artists. Its targets are the hypocritical in- telligentsia, capitalist culture manipulation, consumerism, American and other Molochs. Their aim: total unabashed self-expression in art leading to 02 social involvement .” 02 Boris Lurie was a cofounder and strong proponent of the NO!art move- BORIS LURIE/SEYMOR KRIM/ARMIN ment, into which new artists continued to be incorporated. This t ext t akes HUNDERTMARK (EDS.) NO!Art. PIN-UPS, up various aspects of NO!art between 1959 and 1964/ 65, a phase that Lurie EXCREMENT, PRO- 03 TEST, JEW ART, 03 himself de ✂ned as “collective.” On the NO!art website that Dietmar Kirves Berlin/Cologne: Edition ESTERA MILMAN initiated in Berlin in 2000 with Lurie’s support, NO!art is represented by di- Hundertmark, 1988, NO!art and the Aesthet- p. 13. ics of Doom. Boris verse and disparate young artistic positions, as was already the case with Lurie & Estera Milman: One-on-One, 148 min., the earlier March Group. -

VIOLATED! Women in Holocaust and Genocide a Group Art Exhibition By

For Immediate Release: March 15, 2018 VIOLATED! Women in Holocaust and Genocide A Group Art Exhibition by Remember the Women Institute April 12 – May 12, 2018 Artists: Rostam Aghala, Ofri Akavia, Judy Chicago & Donald Woodman, Ayana Friedman, Regina José Galindo, Nechama Golan, Muriel (Nezhnie) Helfman, Shosh Kormosh, Mitch Lewis, Judith Weinshall Liberman, Ella Liebermann-Shiber, Boris Lurie, Haim Maor, Naomi Markel, Anat Masad, Mary Mihelic, Dvora Morag, Halina Olomucki, Zeev Porath (Wilhelm Ochs), Rachel Roggel, Manasse Shingiro, Hana Shir, Li Shir, Nancy Spero, Linda Stein, Yocheved Weinfeld, Gil Yefman and the Kuchinate women, Racheli Yosef, Safet Zec, Dvora (Veg) Zelichov, Ronald Feldman Gallery will exhibit VIOLATED! Women in Holocaust and Genocide, an exhibition of more than thirty international artists who present artistic representations of and reactions to sexual violence against women during the Holocaust, as well as later genocides. Although there has been extensive documentation of the violence of the Holocaust, sexual violence against women has mostly been covered up or denied. Women who survive today’s genocides, like Holocaust survivors, are frequently silenced by their own unwarranted sense of shame. The exhibition uncovers the past and confronts the present in order to include women’s stories as education for the future. The artworks commemorate and reflect upon this violence and serve to inform viewers about this missing part of history, encouraging empathy and shedding light on this heinous component of genocide. To lift the silence is to move past despair to hope and gives women a voice. Artists include Holocaust survivors, their close relatives, witnesses, and concerned others. Featured are two artworks done secretly inside Nazi concentration camps, borrowed from the Ghetto Fighters’ House, Israel, and works by Boris Lurie, a Holocaust survivor and co-founder of the NO!art movement in the United States in 1960. -

2019–2020 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2019–20 Dear Friends, This annual report was finalized in a world that was unthinkable when the year began. Even though such a report typically looks back, this unprecedented moment calls for looking forward. The Museum is now an all-digital, all-the-time enterprise, for how long we do not know. But that alone is not enough. This is a time for learning and growing. Our digital education resources and virtual trainings and programs must serve our many diverse partners and audiences—teachers, faculty, students, leaders, and the general public. But, we have learned that in digital education, quantity is not quality, and that virtual education is much more complex than we imagined. Demand for our online resources and teaching support has soared, and we are experimenting and reimagining our work for this new world. Our role has always been to help build and lead the fields of Holocaust scholarship and education as well as genocide prevention. Now these fields face challenges and opportunities as never before. Thanks to your ongoing generosity, the Museum is well positioned to learn from this crisis and grow into an even stronger, more impactful institution, whose educational message is more urgent than ever. Thank you, Howard M. Lorber, Chairman Allan M. Holt, Vice Chairman Sara J. Bloomfield, Director FOUNDERS SOCIETY Gifts as of August 7, 2020 The Museum is deeply grateful to our leading donors, whose cumulative gifts of $1 million or more make our far-reaching impact possible. GUARDIANS OF MEMORY PILLARS OF MEMORY Planethood Foundation, Inc. The Chrysler Corporation Fund Doris and Simon* Konover Judith B. -

1 Ivonna Veiherte`S Interwiev with Gertrude Stein in September 2018

Ivonna Veiherte`s interwiev with Gertrude Stein in September 2018 in New York From the left: Vita Birzaka, Ivonna Veiherte, Gertrude Stein, Daiga Upeniece. New York, 2018. Photo: Rafael Vostell No!art is not imaginable without you. Can you please tell us about how you started working in art? Did your family collect art or was it involved in art in any way? We had pictures around, my family collected Bauhaus1, but we were mostly a political family. A political family? What do you mean? We were very much involved in fighting prejudice, in working against anti-Semitism and helping Israel, in helping war veterans – we did a lot of that sort of work. 1 The Staatliches Bauhaus commonly known as the Bauhaus, was a German art school that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. The Bauhaus was founded by Walter Gropius in 1918. 1 Did you study art? I studied art and literature, and then started out as an artist. I started collecting very early, and opened a gallery pretty early, right around the time I met Boris2. The March Gallery, which he ran, was very exciting and very inventive and I became very much involved with the people he worked with and in the kind of art he did. We got together and opened a gallery on the Upper East Side that showed NO!art only. How did you meet Boris? What was he like as a person? How did he live? I met Boris through a great friend of ours, Elmer Kline, a writer and poet. -

In-Riga-Boris-Lurie-Memoir-SAMPLE

IN RIGA IN RIGA A MEMOIR BORIS LURIE EDITED AND INTRODUCED BY JULIA KISSINA Copyright © 2019 NO!art Publishing I thank you Adolf Hitler for having made of me what I am, for all the fruitful hours I did spend in your hand, for all the precious Introduction © Julia Kissina lessons I have learned due to your wisdom, for all the tragic NO!art Publishing is the publishing arm of the Boris Lurie Art Foundation moments suspended between life and death. No part of the present text may be used or reproduced in any manner without the written permission of the Boris Lurie Art Foundation, except – Boris Lurie in the context of reviews. First edition ISBN: 978-0-578-51209-9 Boris Lurie Art Foundation 50 Central Park West New York, NY 10023 USA borislurieart.org Edited by Julia Kissina Cover design by Chris Shultz Book design by Harold Wortsman Printed in the USA THE INFERNO OF MEMORY, THE PARADISE OF CREATION Avant-garde always follows historic tragedy. Te Russian avant-garde was a response to the Revolution, Dadaism — to the First World War. Boris Lurie, whose life is deeply entwined with the key events of the twentieth century, belongs to the generation of avant-garde’s second wave, spawned by World War II. Boris Iliyich Lurie was born in Leningrad in 1924. His mother was a dentist. His father supplied the Red Army with leather goods. He had two older sisters: Assya and Jeanna. Boris’s childhood unfolded against the background of complex political upheaval. Following Lenin’s death, repression spread across Soviet Russia. -

Art Review: “Unorthodox Exhibition” in the New York Jewish Museum

Vol. 18, No. 2 International Journal of Multicultural Education 2016 Art Review: “Unorthodox Exhibition” in the New York Jewish Museum Hwa Young Caruso Art Review Editor “To stage an exhibition entitled Unorthodox in the context of the Jewish Museum might seem provocative, but the title does not refer to a critique of religious orthodoxy; rather, it speaks of orthodoxies in the plural, meaning, anything and everything that is culturally, socially, or politically normative….Art, after all, can be a brilliant means to probe previously unquestioned truths, and to allow unorthodox concepts to infiltrate orthodox systems.” -- Jens Hoffmann, Daniel Palmer, and Kelly Taxter (Jewish Museum Staff) Held between November 2015 and March 2016, the Jewish Museum’s exhibition of 55 artists with 200 artworks was like a creative Tsunami of expression and media. The task of arranging the works without overwhelming viewers was daunting but thoughtfully executed by Museum Deputy Director Jens Hoffmann and Curators Daniel Palmer and Kelly Taxter. This visual buffet provided ample amounts of cognitive and emotional nourishment to satisfy everyone’s aesthetic appetite. The 200 plus artworks were organized in a thematic sequence which included 14 threads: boundaries, canon, complications, conventions, divergence, gaze, iconoclasm, individual, intensity, lies, mythologies, order, secrets, and taste. What initially caught my eyes were the mixed media bicycle constructions by Cryrus Kabiru, who was born in 1984 in Nairobi, Kenya. Two bicycles, entitled “Future Bicycle I” (2014) and “Future Bicycle II” (2014), were constructed from discarded materials. From a distance Kabiru’s works appear to be original bicycles ornately decorated. Upon closer inspection one discovers that the components are ordinary items that were collected, recycled, repurposed, and reorganized to become bikes for aesthetic purposes.