Thresholds to Middle-Earth: Allegories of Reading, Allegories for Knowledge and Transformation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lord of the Rings: the Card Game Scenarios, a Select Few Are Only Intended for Use When Playing the Scenarios Presented in the Hobbit Saga Expansions

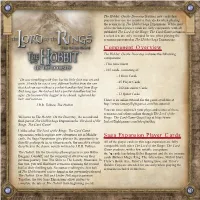

The Hobbit: On the Doorstep features new cards that players may use to customize their decks when playing the scenarios in The Hobbit Saga Expansions. While most of the included player cards are fully compatible with all published The Lord of the Rings: The Card Game scenarios, a select few are only intended for use when playing the scenarios presented in The Hobbit Saga Expansions. Component Overview ™ The Hobbit: On the Doorstep includes the following components: - This rules insert - 165 cards, consisting of: - 5 Hero Cards “He was trembling with fear, but his little face was set and grim. Already he was a very different hobbit from the one - 45 Player Cards that had run out without a pocket-handkerchief from Bag- - 102 Encounter Cards End long ago. He had not had a pocket-handkerchief for ages. He loosened his dagger in its sheath, tightened his - 13 Quest Cards belt, and went on.” There is an online tutorial for the game available at –J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit http://www.fantasyflightgames.com/lotr-tutorial You can enter and track your plays and scores of these scenarios and others online through The Lord of the Welcome to The Hobbit: On the Doorstep, the second and Rings: The Card Game Quest Log at http://www. final part of The Hobbit Saga Expansion for The Lord of the fantasyflightgames.com/lotr-questlog. Rings: The Card Game! Unlike other The Lord of the Rings: The Card Game expansions, which explore new adventures set in Middle- Saga Expansion Player Cards earth, the Saga Expansions give players the opportunity to directly participate in, or even recreate, the narrative events All of the player cards in this saga expansion are fully described in the classic novels written by J.R.R. -

© 2019 C.Wilhelm

© 2019 C.Wilhelm Questions About THE HOBBIT The Unexpected Journey, Movie 1, 2012 Name ________________________________ Date _____________ 1. Who was telling (writing) the story in the movie? _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ 2. What happened to ruin the peaceful, prosperous Lonely Mountain and the Mines of Moria? _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ 3. Why do the Dwarves want their ancestral home back? _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ 4. Why does Thorin especially want to fight the pale Orc? _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ 5. How does Bilbo Baggins become involved in the quest to enter Lonely Mountain? _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ 6. Why does the company need Bilbo’s help? _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ 7. Which groups in the story especially love food? _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ Page 1 © 2019 C.Wilhelm THE HOBBIT questions continued Name ________________________________ Date _____________ 8. Do the Dwarves have good table manners? Explain. _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ 9. Did you notice the map in the beginning of the story? Is -

Readers' Guide

Readers’ Guide for by J.R.R. Tolkien ABOUT THE BOOK Bilbo Baggins is a hobbit— a hairy-footed race of diminutive peoples in J.R.R. Tolkien’s imaginary world of Middle-earth — and the protagonist of The Hobbit (full title: The Hobbit or There and Back Again), Tolkien’s fantasy novel for children first published in 1937. Bilbo enjoys a comfortable, unambitious life, rarely traveling any farther than his pantry or cellar. He does not seek out excitement or adventure. But his contentment is dis- turbed when the wizard Gandalf and a company of dwarves arrive on his doorstep one day to whisk him away on an adventure. They have launched a plot to raid the treasure hoard guarded by Smaug the Magnificent, a large and very dangerous dragon. Bilbo reluctantly joins their quest, unaware that on his journey to the Lonely Mountain he will encounter both a magic ring and a frightening creature known as Gollum, and entwine his fate with armies of goblins, elves, men and dwarves. He also discovers he’s more mischievous, sneaky and clever than he ever thought possible, and on his adventure, he finds the courage and strength to do the most surprising things. The plot of The Hobbit, and the circumstances and background of magic ring, later become central to the events of Tolkien’s more adult fantasy sequel, The Lord of the Rings. “One of the best children’s books of this century.” — W. H. AUDEN “One of the most freshly original and delightfully imaginative books for children that have appeared in many a long day . -

The Implied Reader and the Recovery of Childhood: a Study of J.R.R

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2019 The Implied Reader and the Recovery of Childhood: A Study of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit Georgette Talaat Rizk Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Rizk, G. (2019).The Implied Reader and the Recovery of Childhood: A Study of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/734 MLA Citation Rizk, Georgette Talaat. The Implied Reader and the Recovery of Childhood: A Study of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit. 2019. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/734 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences The Implied Reader and the Recovery of Childhood: A Study of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit A Thesis Submitted to the Department of English and Comparative Literature In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Georgette Rizk Under the supervision of Dr. William Melaney October 2018 The American University in Cairo The Implied Reader and the Recovery of Childhood: A Study of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit A Thesis Submitted by Georgette Rizk To the Department of English and Comparative Literature October 2018 In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The degree of Master of Arts Has been approved by Dr. -

The Geology of Middle-Earth

Volume 21 Number 2 Article 50 Winter 10-15-1996 The Geology of Middle-earth William Antony Swithin Sarjeant Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Sarjeant, William Antony Swithin (1996) "The Geology of Middle-earth," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 21 : No. 2 , Article 50. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol21/iss2/50 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract A preliminary reconstruction of the geology of Middle-earth is attempted, utilizing data presented in text, maps and illustrations by its arch-explorer J.R.R. Tolkien. The tectonic reconstruction is developed from earlier findings yb R.C. Reynolds (1974). Six plates are now recognized, whose motions and collisions have created the mountains of Middle-earth and the rift structure down which the River Anduin flows. -

NAME Retha Lee PERIOD 1 DATE 8/29/18 EXAMPLE

NAME Retha Lee PERIOD 1 DATE 8/29/18 EXAMPLE: Self-Selected Reader Response Journal Section I: Due August 29, 2018 (25 points) THE DATES ARE SET AND WILL COUNT AS A SUMMATIVE ASSESSMENT WHEN ALL THREE SECTIONS ARE COMPLETED. NO SECTION WILL BE ACCEPTED LATE. BOOK TITLE The Hobbit # OF PAGES 1-122 AUTHOR J.R.R. Tolkien PUBLISHER Houghton Mifflin Company SETTING: Describe IN DETAIL the setting of the book that you read. If more than one setting was involved, be sure to include all details. Also comment on the time period of the setting. The Hobbit is set in "Middle-earth," a fantasyland created by Tolkien. Within Middle-earth, The Hobbit is limited to settings in the Western lands. It begins in Hobbiton, a town in the Shire, a peaceful area usually untouched by troubles elsewhere in the world. Tell who the main character(s) are and how do you know this? Bilbo Baggins is the main character of J.R.R. Tolkien's 'The Hobbit'. He lives a quiet and simple life until an unexpected adventure changes everything. Bilbo is a hobbit from the Shire, a small, out-of-the-way place in Middle-Earth. He is in his prime of life at the age of 50. He is small in height, with large hairy feet and curly hair. As a hobbit he appreciates a good pint, his pipe, and the comforts of home; travel and adventure were not things he took part in. That is until a group of dwarves barge into his home. They are under the impression that they are hiring him to be their resident thief, thanks to Gandalf, the mischievous wizard, who advised Bilbo would be up to the task. -

Short History of the Territorial Development of the Dwarves' Kingdoms in the Second and Third Ages of Middle-Earth

Volume 21 Number 2 Article 59 Winter 10-15-1996 Short History of the Territorial Development of the Dwarves' Kingdoms in the Second and Third Ages of Middle-earth Hubert Sawa Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Sawa, Hubert (1996) "Short History of the Territorial Development of the Dwarves' Kingdoms in the Second and Third Ages of Middle-earth," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 21 : No. 2 , Article 59. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol21/iss2/59 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract This speculative paper, discusses the emergence of the kingdoms of the Dwarves, changes in their borders, and different factors influencing them (e.g. wars with Elves and Orcs). -

The Medieval Cardinal Virtues in Tolkien's the Hobbit

The Medieval Cardinal Virtues in Tolkien’s The Hobbit BA Thesis Anne Sieberichs Student Number: 1271233 Online Culture: Art, Media and Society / Global Communication / Digital Media Department of Culture Studies School of Humanities and Digital Sciences Date: July 2020 Supervisor: Dr. Inge van der Ven Second Reader: Dr. Sander Bax ‘There is a lot more in him than you guess, and a deal more than he has any idea of himself.’1 1 J.R.R Tolkien, The Hobbit, or There and Back Again (United Kingdom: HarperCollinsPublishers, 2011), 19. 2 Table of contents 1.0 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………. 4 1.1 Method………………………………………………………………………………… 5 1.2 Previous Research on Tolkien………………………………………………………….7 1.3 Tolkien’s Opus and The Hobbit………………………………………………………. 8 2.0 A Short History of Cardinal Virtues in the Middle Ages………………………………………9 3.0 Medieval Cardinal Virtues in Tolkien’s opus………………………………………………….11 3.1 Christianity and Tolkien……………………………………………………………….11 3.2 Prudence: ‘For even the very wise cannot see all ends.’2……………………………...12 3.2.1 Gandalf the prudent in The Hobbit………………………………………….15 3.3 Justice: ‘There is more in you of good than you know, child of the kindly West.’ 3….17 3.3.1 the case of Justice through the Arkenstone in The Hobbit………………….18 3.4 Fortitude: ‘But I expect they had lots of chances, like us, of turning back, only they didn’t.’4…………………………………………………………………………………….21 3.4.1. Fortitude: A case study of Bilbo’s Fortitude in The Hobbit………………… 24 3.5 Temperance: ‘If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world.’5………………………………………………………………. -

Other Minds Magazine, Issue 1

OTHER MINDS MAGAZINE OOTHERTHER MMINDSINDS The Unofficial Role-Playing Magazine for J.R.R. Tolkien‘s Middle-earth and beyond Other Minds Content Magazine Main Features Issue 1 2 Editorial: Here we are! July 2007 3 Opinion: The Acroteriasm of Other Hands Hawke Robinson Publisher 6 The Battle over Role Playing Gaming Other Minds Volunteers Hawke Robinson Editors Assistant Editors 9 Mapping Arda Hawke Robinson Chris Seeman Thomas Morwinsky,Stéphane Hœrlé, Gabriele Thomas Morwinsky Chris Wade Quaglia, Oliver Schick, Christian Schröder 21 Of Barrow-wights Art Director Neville Percy Hawke Robinson 28 Magic in Middle-earth Production Staff Chris Seeman Thomas Morwinsky Hawke Robinson 31 Thoughts on Imladris Thomas Morwinsky Other Features 37 Fineprint 38 Creative Commons license Appendix: Maps of Arda For use with “Mapping Arda” Next Issue’s featured theme will be: Númenor Unless otherwise noted, every contribution in this magazine is published under the CreaticeCommons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license (b n a) The exact license of a given contribution can be found at the beginning of each contribution. OTHER MINDS MAGAZINE you want to see your adventure, realm de- scription, or whatever else in print – you know whom to look for! We are especially in need of good artists Editorial and images to enhance the magazine with original art. If you submit someone else’s art, please add a written approval from the artist. the Tolkien-related content of course). More Here we are! Now, for the actual content of this inaugu- of the team will be introduced in later issues. Perhaps you know the famous Fantasy ral issue: First we have an insightful essay in movie in whose title track this line is the 1 the category “Opinion” by Hawke Robinson, opener – and how it continued. -

Tolkien's Inspirations and Influences in His Book, Intentionally It Seems

Last updated 9 March 2008 Tolkien’s inspirations and influences on his works An alphabetical entry list compiled by Ardamir of the Lord of the Rings Fanatics Forum (http://www.lotrplaza.com/forum/) While reading J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography by Humphrey Carpenter about 2½ years ago, I noticed that he mentions many of Tolkien's inspirations and influences in his book, intentionally it seems. I took the opportunity to start listing these inspirations along with their sources, and have since then used many other sources for my list. I am listing elements in Tolkien's works in alphabetical order, along with their respective inspirations, and the sources I have used. Many of the inspirations are (very) speculative, and those I have marked with a '?', but some are obvious. The list is not meant (at least not yet) to be a detailed investigation of Tolkien's inspirations but rather to include just the relevant information and gather all the inspirations in one place for each entry. I know that it has many defects, and it is somewhat lacking in sources and references, but I am constantly improving it while adding more and more inspirations. I would greatly appreciate it if other people would take a look at it and tell me what they think about it, and also suggest additions and improvements. I am not making the list just for the benefit of myself, but for everyone. I update the list almost every day. Bolded (emphasized) parts of quotes by me. Entries that are names are in italics. Entries for text passages can be found in a separate section at the end. -

Questions About the HOBBIT the Unexpected Journey, Movie 1, 2012

Questions About THE HOBBIT The Unexpected Journey, Movie 1, 2012 Name ________________________________ Date _____________ 1. Who was telling (writing) the story in the movie? _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ 2. What happened to ruin the peaceful, prosperous Lonely Mountain and the Mines of Moria? _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ 3. Why do the Dwarves want their ancestral home back? _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ 4. Why does Thorin especially want to fight the pale Orc? _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ 5. How does Bilbo Baggins become involved in the quest to enter Lonely Mountain? _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ 6. Why does the company need Bilbo’s help? _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ 7. Which groups in the story especially love food? _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ Page 1 @2013 by Carolyn Wilhelm for free educational use only on Wise Owl Factory associated sites, credits on page 3 THE HOBBIT questions continued Name ________________________________ Date _____________ 8. Do the Dwarves have good table manners? Explain. _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ -

Song of the Lonely Mountain

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU Honors Projects Honors College Fall 2013 Song of the Lonely Mountain Allison Davis [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects Repository Citation Davis, Allison, "Song of the Lonely Mountain" (2013). Honors Projects. 96. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects/96 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Allison Davis Honors Project in Music Education and Music Performance Proposal Song of the Lonely Mountain for Clarinet Ensemble Song of the Lonely Mountain for Clarinet Ensemble As stated in the guidelines for the Honors Project, “the Honors Project demonstrates a student’s culmination of learning throughout their undergraduate experience. As the final demonstration of a student’s learning, the Honors Project will demonstrate a satisfactory level of learning within the four privileged learning outcomes: oral communication, written communication, integrative learning, and critical thinking.” Based on that definition, I believe that my Honors Project, Song of the Lonely Mountain for Clarinet Ensemble , became an incredibly worthwhile project on a multitude of levels by the time of its completion. The primary goal of this “creative form” project was to arrange a piece for my senior recital that would be entertaining as well as serve an educational purpose for all involved. The piece that was arranged in this case is titled Song of the Lonely Mountain , the music of which is featured in the modern film The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey based off of the popular novel written by J.R.R.