Global Realities: Precarious Survival and Belonging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Qing Challenge in Chosŏn Korea

Readings from Asia The Qing Challenge in Chosŏn Korea Yuanchong Wang, University of Delaware Wang, Yuanchong. 2019. “The Qing Challenge in Chosŏn Korea.” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review 33: 253–260. https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue- 33/readings-asia. Sun Weiguo 孫衛國 . Cong “zun Ming” dao “feng Qing”: Chaoxian wangchao dui Qing yishi de shanbian, 1627–1910 從 “ 尊明 ” 到 “ 奉清 ” : 朝鮮王朝對清意識的嬗變 , 1627–1910 [From “honoring the Ming” to “submitting to the Qing”: The transformation of Chosŏn Korea’s attitude toward Qing China, 1627–1910]. Taipei: Taida chuban zhongxin, 2018. 580 pp. ISBN: 9789863503088. In 1637, the Manchu-ruled Great Qing Country (Manchu Daicing gurun, Ch. Da Qing guo 大清國 ), founded in 1636, invaded and conquered its neighboring country, the Chosŏn kingdom of Korea. After Chosŏn then changed from being a tributary state of the Ming dynasty of China (1368–1644), a bilateral relationship officially established in 1401, to a tributary state of the Great Qing. The relationship between the Qing and Chosŏn lasted for 258 years until it was terminated by the Sino-Japanese Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895. Within the hierarchical Sinocentric framework, to which scholars generally refer in English as the “tributary system,” Koreans had regarded Chosŏn as “Little China” (Xiao Zhonghua 小中華 ) since the Ming period and treated the Jurchens (who changed their name to “Manchu” in the early 1630s) in Manchuria as barbarians. The Sinocentric framework determined that the political legitimacy of Chosŏn, in particular the kingship, came from the imperial acknowledgment by the Chinese court conspicuously represented by the Chinese emperor’s investiture of the Korean king. -

Publications Were Issued in Latin Or German

August 23–28, 2016 St. Petersburg, Russia EACS 2016 21st Biennial Conference of the European Association for Chinese Studies Book of ABStractS 2016 EACS- The European Association for Chinese Studies The European Association for Chinese Studies (EACS) is an international organization representing China scholars from all over Europe. Currently it has more than 700 members. It was founded in 1975 and is registered in Paris. It is a non-profit orga- nization not engaging in any political activity. The purpose of the Association is to promote and foster, by every possible means, scholarly activities related to Chinese Studies in Europe. The EACS serves not only as the scholarly rep- resentative of Chinese Studies in Europe but also as contact or- ganization for academic matters in this field. One of the Association’s major activities are the biennial con- ferences hosted by various centres of Chinese Studies in diffe- rent European countries. The papers presented at these confer- ences comprise all fields from traditional Sinology to studies of modern China. In addition, summer schools and workshops are organized under the auspices of the EACS. The Association car- ries out scholarly projects on an irregular basis. Since 1995 the EACS has provided Library Travel Grants to support short visits for research in major sinological libraries in Western Europe. The scheme is funded by the Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation and destined for PhD students and young scholars, primarily from Eastern European countries. The EACS furthers the careers of young scholars by awarding a Young Scholar Award for outstanding research. A jury selects the best three of the submitted papers, which are then presented at the next bi-an- nual conference. -

Izu Peninsula Geopark Promotion Council

Contents A. Identification of the Area ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 A.1 Name of the Proposed Geopark ........................................................................................................................................... 1 A.2 Location of the Proposed Geopark ....................................................................................................................................... 1 A.3 Surface Area, Physical and Human Geographical Characteristics ....................................................................................... 1 A.3.1 Physical Geographical Characteristics .......................................................................................................................... 1 A.3.2 Human Geographical Charactersitics ........................................................................................................................... 3 A.4 Organization in charge and Management Structure ............................................................................................................. 5 A.4.1 Izu Peninsula Geopark Promotion Council ................................................................................................................... 5 A.4.2 Structure of the Management Organization .................................................................................................................. 6 A.4.3 Supporting Units/ Members -

Bridled Tigers: the Military at Korea's Northern Border, 1800–1863

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Bridled Tigers: The Military At Korea’s Northern Border, 1800–1863 Alexander Thomas Martin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Alexander Thomas, "Bridled Tigers: The Military At Korea’s Northern Border, 1800–1863" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3499. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3499 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3499 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bridled Tigers: The Military At Korea’s Northern Border, 1800–1863 Abstract The border, in late Chosŏn rhetoric, was an area of pernicious wickedness; living near the border made the people susceptible to corruption and violence. For Chosŏn ministers in the nineteenth century, despite two hundred years of peace, the threat remained. At the same time, the military institutions created to contain it were failing. For much of the late Chosŏn the site of greatest concern was the northern border in P’yŏngan and Hamgyŏng provinces, as this area was the site of the largest rebellion and most foreign incursions in the first half of the nineteenth century. This study takes the northern border as the most fruitful area for an inquiry into the Chosŏn dynasty’s conceptions of and efforts at border defense. Using government records, reports from local officials, literati writings, and local gazetteers, this study provides a multifaceted image of the border and Chosŏn policies to control it. This study reveals that Chosŏn Korea’s concept of border defense prioritized containment over confrontation, and that their policies were successful in managing the border until the arrival of Western imperial powers whose invasions upended Chosŏn leaders’ notions of national defense. -

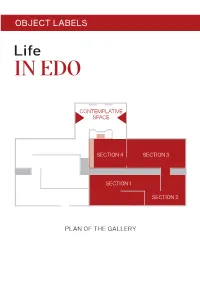

Object Labels

OBJECT LABELS CONTEMPLATIVE SPACE SECTION 4 SECTION 3 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 PLAN OF THE GALLERY SECTION 1 Travel Utagawa Hiroshige Procession of children passing Mount Fuji 1830s Hiroshige playfully imitates with children a procession of a daimyo passing Mt Fuji. A popular subject for artists, a daimyo and his entourage could make for a lively scene. During Edo, daimyo were required to travel to Edo City every other year and live there under the alternate attendance (sankin- kōtai) system. Hundreds of retainers would transport weapons, ceremonial items, and personal effects that signal the daimyo’s military and financial might. Some would be mounted on horses; the daimyo and members of his family carried in palanquins. Cat. 5 Tōshūsai Sharaku Actor Arashi Ryūzō II as the Moneylender Ishibe Kinkichi 1794 Kabuki actor portraits were one of the most popular types of ukiyo-e prints. Audiences flocked to see their favourite kabuki performers, and avidly collected images of them. Actors were stars, celebrities much like the idols of today. Sharaku was able to brilliantly capture an actor’s performance in his expressive portrayals. This image illustrates a scene from a kabuki play about a moneylender enforcing payment of a debt owed by a sick and impoverished ronin and his wife. The couple give their daughter over to him, into a life of prostitution. Playing a repulsive figure, the actor Ryūzō II made the moneylender more complex: hard-hearted, gesturing like a bully – but his eyes reveal his lack of confidence. The character is meant to be disliked by the audience, but also somewhat comical. -

Cycle Train in Service! Rental Cycle Izu Vélo Shuzenji Station L G *The Required Time Shown Is the Estimated Time for an Electrical Assist Bicycle

Required time: about 4hours and 20minutes (not including sightseeing/rest time) Mishima Station Exploring in Mishima City - Hakone Pass - Numazu Station Atami Station Challenging Cyc Daiba Station course - Jukkoku Pass - Daiba Station Course START o lin Cycle Train in Service! Rental Cycle izu vélo Shuzenji Station l g *The required time shown is the estimated time for an electrical assist bicycle. é Izuhakone Railway 28 minutes Izuhakone Railway v M Izu-Nagaoka Station Cycle Train Service Zone JR Ito Line Izu City will host the cycling competition Mishima-Futsukamachi Station *Can be done in the opposite direction a Japan Cycle at the Olympic and Paralympic Games Tokyo 2020 ↑Ashinoko Lake u Sports Center About 1.3 km ( Track Race and Mountain Bicycle ) Hakone Pass z p Mishima Taisha Shrine i Hakone Ashinoko-guchi ◇Track Race Venue: Izu Velodrome ★ Minami Ito Line Izu City Susono About 2.2 km ★ ly the Heda Shuzenji Station Mountain Bicycle Venue: Izu Mountain Bicycle Course Grand Fields On ◇ p Country Club a i Nishikida Ichirizuka Historic Site z est u St b Nakaizu M u Toi Port Yugashima Gotemba Line nn Kannami Primeval Forest About 13.5 km v ing ♪ g s Izu Kogen Station é The train is National Historic Site: n V l i seat Joren Falls i ews! Hakone Pass o Enjoy the Izu l Mishima-Hagi Juka Mishima Skywalk Yamanaka Castle Ruins c n now departing! Lover’s Cape Ex ★ Izu Peninsula p About 8.7 km y Find the re C s bicycle that a s Children’s Forest Park Izukyu Express w Jukkoku Pass Rest House to the fullest! best for a Kannami Golf Club Tokai -

Makie Masterpieces of My Choice by Kazumi MUROSE

JAPANESE CRAFT & ART 1 Urushi in Japanese Culture (2) Makie Masterpieces of My Choice By Kazumi MUROSE Trends in the style of makie (a traditional way of decorating In 1996, I was made a leader of a team responsible for making urushi ware comparable to gold-relief lacquer painting) can be a replica of this tebako, and spent two years closely examining broadly divided into two groups – the traditional style that has the box, down to its smallest detail. The project involved not just continued from the Heian period (794-1192) to this day, and the making a replica, but employing as closely as possible the mate- diversified style that flourished in the periods of Azuchi- rials and methods that were used in making the original. It was a Momoyama (1568-1603) and Edo (1603-1867). I would like to process that enabled me to look squarely at the art of craftsmen introduce in this article four masterpieces in line with these in the Kamakura era (1192-1333), and I learned a lot. When I trends. actually restored the methods of that period, I found that despite using almost excessively sophisticated techniques, the crafts- “Ume Makie Tebako”: Flowering Traditional Style men did not make an ostentatious show of them, giving the box a deceptively simple, graceful look. This was an eye-opener for Of many masterpieces from the medieval period, one item I me. “Ume Makie Tebako” shows the traditional style of the early have a special feeling for is “Ume Makie Tebako” (box with plum period at its best, a style that has been seamlessly handed on. -

1 INTRODUCTION Accounts of Taiwan and Its History Have Been

INTRODUCTION Accounts of Taiwan and its history have been profoundly influenced by cultural and political ideologies, which have fluctuated radically over the past four centuries on the island. Small parts of Taiwan were ruled by the Dutch (1624-1662), Spanish (1626-1642), Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga)1 and his heirs (1662-1683), and a large part by Qing Dynasty China (1683-1895). Thereafter, the whole of the island was under Japanese control for half a century (1895-1945), and after World War II, it was taken over by the Republic of China (ROC), being governed for more than four decades by the authoritarian government of Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang (KMT), or Chinese Nationalist Party,2 before democratization began in earnest in the late 1980s. Taiwan’s convoluted history and current troubled relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which claims Taiwan is “a renegade province” of the PRC, has complicated the world’s understanding of Taiwan. Many Western studies of Taiwan, primarily concerning its politics and economic development, have been conducted as an 1 Pinyin is employed in this dissertation as its Mandarin romanization system, though there are exceptions for names of places which have been officially transliterated differently, and for names of people who have been known to Western scholarship in different forms of romanization. In these cases, the more popular forms are used. All Chinese names are presented in the same order as they would appear in Chinese, surname first, given name last, unless the work is published in English, in which case the surname appears last. -

Yatagarasu (Gagak Berkaki Tiga) Sebagai Objek Pemujaan Pada Kuil Shinto Kumano Hongu Taisha Di Prefektur Wakayama

YATAGARASU (GAGAK BERKAKI TIGA) SEBAGAI OBJEK PEMUJAAN PADA KUIL SHINTO KUMANO HONGU TAISHA DI PREFEKTUR WAKAYAMA WAKAYAMA KEN DE NO KUMANO HONGU TAISHA SHINTO NI SHUUHAI NO TAISHOU TO SHITE NO YATAGARASU SKRIPSI Skripsi ini diajukan kepada panitia ujian Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara Medan untuk melengkapi salah satu syarat ujian Sarjana dalam bidang Ilmu Budaya Sastra Jepang Oleh: ARIN RIFKA ANNISA 140708053 PROGRAM STUDI SASTRA JEPANG FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2019 i UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA ii UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA KATA PENGANTAR Puji syukur penulis panjatkan atas segala anugerah dan karunia dari Tuhan Yang Maha Esa sehingga penulis dapat menyelesaikan penelitian yang berjudul ―YATAGARASU (GAGAK BERKAKI TIGA) SEBAGAI OBJEK PEMUJAAN PADA KUIL SHINTO KUMANO HONGU TAISHA DI PREFEKTUR WAKAYAMA”. Dalam skripsi ini penulis membahas hal-hal yang berhubungan dengan yatagarasu (gagak berkaki tiga) sebagai objek pemujaan pada kuil shinto kumano hongu taisha. Namun, karena keterbatasan pengetahuan dan kemampuan penulis serta bahan literatur, penulis menyadari masih banyak kekurangan dalam penulisan skripsi ini. Maka dari itu, penulis dengan senang hati menerima kritik dan saran untuk kesempurnaan penulisan skripsi ini. Penulis juga menyadari bahwa penulisan skripsi ini tidak akan selesai tanpa bantuan dan dukungan dari semua pihak yang telah banyak membantu penulis dalam penyusunan skripsi ini. Maka sepantasnya penulis mengucapkan terima kasih kepada: 1. Bapak Dr. Budi Agustono, M.S., selaku Dekan Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara, yang telah membantu peulis dalam menyediakan sarana dan fasilitas belajar selam masa perkuliahan. 2. Bapak Prof. Hamzon Situmorang,M.S,Ph.D., selaku ketua Jurusan Sastra Jepang Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara, yang dengan tulus ikhlas membimbing, memeriksa dan memberikan saran-saran serta arahan dalam rangka perbaikan dan penyempurnaan skripsi ini. -

INTERACTIONS and RELATIONS BETWEEN KOREA, JAPAN and CHINA DURING the MING-QING TRANSITION by SI

THROUGH THEIR NEIGHBORS’ EYES: INTERACTIONS AND RELATIONS BETWEEN KOREA, JAPAN AND CHINA DURING THE MING-QING TRANSITION by SIMENG HUA A THESIS Presented to the Department of History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts March 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Simeng Hua Title: Through Their Neighbors’ Eyes: Interactions and Relations between Korea, Japan and China during the Ming-Qing Transition This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of History by: Ina Asim Chairperson Andrew Goble Member Yugen Wang Member and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded March 2017 ii © 2017 Simeng Hua iii THESIS ABSTRACT Simeng Hua Master of Arts Department of History March 2017 Title: Through Their Neighbors’ Eyes: Interactions and Relations between Korea, Japan and China during the Ming-Qing Transition In the period from the sixteenth century to the eighteenth century, East Asia witnessed changes in the Chinese tribute system, the downfall of the Ming Dynasty, the Manchu invasion of Korea, the establishment of the Tokugawa bakufu in Japan, and the prosperity of the High Qing era. This extraordinary period disrupted the existing China- centered diplomatic system; however, at the same time, a fertile ground was created for new perceptions of the respective immediate neighbor for each individual state. In the struggle to achieve or maintain domestic and external stability, intellectuals, officials, and even commoners reflected on ways to express their individual and communal narratives that contributed to their nation’s history. -

Y Ou Can Use Free W I-Fi at the Tourist Route of Mishima- City

Y ou can use free W i- Fi at the tourist route of Mishima- City. ■Name(SSID) Mishima Sta. 100m 200ft MISHIMA FREE Wi-Fi North Mishima Sta. Toruist Information Mishima Sta. Daiba Riv. ■Service Providing Area South Mishima Station North Izuhakone Railway Sunzu-Line Mishima Station South Mishima Tourist Information Book Rakujuen Park Association Shirataki Park Rakujuen Park Shirataki Park Genbe River North-Side Sakura Riv. Genbe River South-Side Hasunuma Riv Genbe River North-Side Goten Riv. Toki-no-kane Bell Mishima Taisha Genbe River Shrine Honcho South-Side The Old Tokaido Road Mishima Taisha Shrine Honcho Commerce and Tourism Division Mishima-Hirokoji Sta. Mishima City Toki-no-kane Bell To Numazu This service can be used free of charge up to 60 minutes in one day. Conditions of Use (The service can be used for 15 minutes per session, up to four sessions in one day.) Use is free of change for everybody. Tourist Information Mishima Tourist Commerce and Tourism Division IZU HAKONE Mt.FUJI 〒411-0036 Association Mishima City 16-1 Ichibancho, 〒411-0036 〒411-8666 Mishima-shi, Shizuoka-ken 2-29 Ichibancho, 4-47 KitaTamachi, TEL: 055-946-6900 Mishima-shi, Shizuoka-ken Mishima-shi, Shizuoka-ken FAX: 055-946-6908 4th floor of the hall of TEL: 055-983-2656 Open all year round Mishima Chamber of Commerce TEL: 055-971-5000 I nq u i r i es I nq u i r i es i nf o @ m i sh i m a - k a nk o u . c o m sy o u k o u @ c i ty . -

Grand Council of the Qing Dynasty, 1853

VMUN 2019 Grand Council of the Qing Dynasty, 1853 CRISIS BACKGROUND GUIDE Vancouver Model United Nations The Eighteenth Annual Session | January 25–27, 2019 Proclaimed in the fourth year of the Xianfeng Era: Jerry Xu Secretary-General To my loyal subjects, I welcome you all to the Grand Council. You are my most loyal and trusted servants, as well as the delegates from Western nations that China has seen fit to recognize. You will have the Nick Young privilege and honour of serving the Emperor, and through me, the heavens. Chief of Staff For centuries, China was the undisputed centre of the world, our lands the envy of all Angelina Zhang civilizations. Yet, our power is no longer unchallenged. Having opened up our culture to the Director-General rest of the world, China now faces chaos of an unprecedented scale since the Great Qing restored order to China two centuries ago—long-haired savages sweep through central China and Western nations exploit our markets with their gunboats. A great flood at the Yellow River has displaced many who live along its banks. Allan Lee Director of Logistics Yet, I have faith that these problems are fleeting and will be resolved swiftly. China endures; China has always endured, with the Mandate of Heaven surviving for thousands of years. Thus Katherine Zheng I entrust to you, my subjects, the fate of the Qing dynasty and China herself. Beijing readies USG General Assemblies itself for defence against imminent attack. I have faith in your ingenuity and ability to restore prosperity to the Empire.