English Writings on Chivalry and Warfare During the Hundred Years War1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr Sally Mapstone “Myllar's and Chepman's Prints” (Strand: Early Printing)

Programme MONDAY 30 JUNE 10.00-11.00 Plenary: Dr Sally Mapstone “Myllar's and Chepman's Prints” (Strand: Early Printing) 11.00-11.30 Coffee 11.30-1.00 Session 1 A) Narrating the Nation: Historiography and Identity in Stewart Scotland (c.1440- 1540): a) „Dream and Vision in the Scotichronicon‟, Kylie Murray, Lincoln College, Oxford. b) „Imagined Histories: Memory and Nation in Hary‟s Wallace‟, Kate Ash, University of Manchester. c) „The Politics of Translation in Bellenden‟s Chronicle of Scotland‟, Ryoko Harikae, St Hilda‟s College, Oxford. B) Script to Print: a) „George Buchanan‟s De jure regni apud Scotos: from Script to Print…‟, Carine Ferradou, University of Aix-en-Provence. b) „To expone strange histories and termis wild‟: the glossing of Douglas‟s Eneados in manuscript and print‟, Jane Griffiths, University of Bristol. c) „Poetry of Alexander Craig of Rosecraig‟, Michael Spiller, University of Aberdeen. 1.00-2.00 Lunch 2.00-3.30 Session 2 A) Gavin Douglas: a) „„Throw owt the ile yclepit Albyon‟ and beyond: tradition and rewriting Gavin Douglas‟, Valentina Bricchi, b) „„The wild fury of Turnus, now lyis slayn‟: Chivalry and Alienation in Gavin Douglas‟ Eneados‟, Anna Caughey, Christ Church College, Oxford. c) „Rereading the „cleaned‟ „Aeneid‟: Gavin Douglas‟ „dirty‟ „Eneados‟, Tom Rutledge, University of East Anglia. B) National Borders: a) „Shades of the East: “Orientalism” and/as Religious Regional “Nationalism” in The Buke of the Howlat and The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedy‟, Iain Macleod Higgins, University of Victoria . b) „The „theivis of Liddisdaill‟ and the patriotic hero: contrasting perceptions of the „wickit‟ Borderers in late medieval poetry and ballads‟, Anna Groundwater, University of Edinburgh 1 c) „The Literary Contexts of „Scotish Field‟, Thorlac Turville-Petre, University of Nottingham. -

Cathar Or Catholic: Treading the Line Between Popular Piety and Heresy in Occitania, 1022-1271

Cathar or Catholic: Treading the line between popular piety and heresy in Occitania, 1022-1271. Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of History William Kapelle, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master’s Degree by Elizabeth Jensen May 2013 Copyright by Elizabeth Jensen © 2013 ABSTRACT Cathar or Catholic: Treading the line between popular piety and heresy in Occitania, 1022-1271. A thesis presented to the Department of History Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Elizabeth Jensen The Occitanian Cathars were among the most successful heretics in medieval Europe. In order to combat this heresy the Catholic Church ordered preaching campaigns, passed ecclesiastic legislation, called for a crusade and eventually turned to the new mechanism of the Inquisition. Understanding why the Cathars were so popular in Occitania and why the defeat of this heresy required so many different mechanisms entails exploring the development of Occitanian culture and the wider world of religious reform and enthusiasm. This paper will explain the origins of popular piety and religious reform in medieval Europe before focusing in on two specific movements, the Patarenes and Henry of Lausanne, the first of which became an acceptable form of reform while the other remained a heretic. This will lead to a specific description of the situation in Occitania and the attempts to eradicate the Cathars with special attention focused on the way in which Occitanian culture fostered the growth of Catharism. In short, Catharism filled the need that existed in the people of Occitania for a reformed religious experience. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

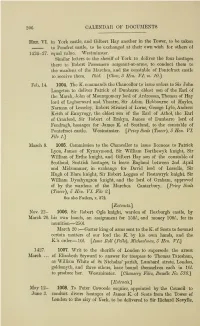

1427 to 1453

206 CALENDAE OF DOCUMENTS Hen. VI. in York castle, and Gilbert Hay another in the Tower, to be taken to Pomfret castle, to be exchanged at their own wish for others of 1426-27. equal value. Westminster. Similar letters to the sheriff of York to deliver the four hostages there to Eobert Passemere sergeant-at-arms, to conduct them to the wardens of the Marches, and the constable of Pontefract castle to receive them. IMd. {^Closc, 5 Hen. VI. m. JO.] Feb. 14. 1004. The K. commands the Chancellor to issue orders to Sir John Langeton to deliver Patrick of Dunbarre eldest son of the Earl of the March, John of Mountgomery lord of Ardrossan, Thomas of Hay lord of Loghorward and Yhestre, Sir Adam Hebbourne of Hayles, Norman of Lesseley, Eobert Stiward of Lome, George Lyle, Andrew Keith of Ennyrugy, the eldest son of the Earl of Athol, the Earl of Crauford, Sir Eobert of Erskyn, James of Dunbarre lord of Fendragh, hostages for James K. of Scotland, to the constable of Pontefract castle. Westminster. {^Privy Seals (Toiuer), 5 Hen. VI. File I] March 8. 1005. Commission to the Chancellor to issue licences to Patrick Lyon, James of Kynnymond, Sir William Borthewyk knight, Sir William of Erthe knight, and Gilbert Hay son of the constable of Scotland, Scottish hostages, to leave England between 2nd April and Midsummer, in exchange for David lord of Lesselle, Sir Hugh of Blare knight. Sir Eobert Loggan of Eestawryk knight, Sir William Dysshyngton knight, and the lord of Graham, approved of by the wardens of the Marches. -

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series Skeat, W.W. ed., The kingis quiar: together with A ballad of good counsel: by King James I of Scotland, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 1 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 2 (1883) Gregor, W. ed., Ane treatise callit The court of Venus, deuidit into four buikis. Newlie compylit be Iohne Rolland in Dalkeith, 1575, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 3 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 4 (1893) Cody, E.G. ed., The historie of Scotland wrytten first in Latin by the most reuerend and worthy Jhone Leslie, Bishop of Rosse, and translated in Scottish by Father James Dalrymple, religious in the Scottis Cloister of Regensburg, the zeare of God, 1596. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 5 (1888) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 6 (1889) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 7 (1889) McNeill, G.P. ed., Sir Tristrem, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 8 (1886) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 9 (1887) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. -

The Art of War in the Middle Ages, A.D. 378-1515

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/artofwarinmiddleOOomanuoft otl^xan: ^rt§e ^ssag 1884 THE ART OF WAR IN THE MIDDLE AGES PRINTED BY HORACE HART, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY THE ART OF WAR [N THE MIDDLE AGES A.D. 37^—15^5 BY C. W. C. OMAN, B.A. FELLOW OF ALL SOULS COLLEGE WITH MAPS AND PLANS OXFORD B. H. BLACKWELL, 50 BROAD STREET LONDON T. FISHER UNWIN, 26 PATERNOSTER SQUARE 1885 [^// rights reserved '\ O/M The Author desires to acknowledge much kind help received in the revision and correction of this Essay from the Rev. H. B. George, of New College, and Mr. F. York Powell, of Christ Church. 6/ 37 05 , — — CONTENTS. PAGE ' Introduction . i CHAPTER 1. The Transition from Roman to Medieval forms in War (a.d. 378-582). Disappearance of the Legion.—Constantine's reorgajiization. The German tribes . — Battle of Adrianople.—Theodosius accepts its teaching.—Vegetius and the army at the end of the fourth century. —The Goths and the Huns. Army of the Eastern Empire.— Cavalry all-important . 3— 14 CHAPTER n. The Early Middle Ages (a.d. 476-1066). Paucity of Data for the period.—The Franks in the sixth cen- tury.—Battle of Tours.—^Armies of Charles the Great. The Franks become horsemen.—The Northman and the Magyar.—Rise of Feudalism.—The Anglo-Saxons and their wars.—The Danes and the Fyrd.—Military importance of the Thegnhood.—The House-Carles.—Battle of Hastings . Battle of Durazzo 15 — 27 W — VI CONTENTS. -

Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 12 2007 Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth- Century Scottish Literature Sally Mapstone St. Hilda's College, Oxford Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mapstone, Sally (2007) "Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 35: Iss. 1, 131–155. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol35/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sally Mapstone Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature Among the voluminous papers of William Drummond of Hawthomden, not, however with the majority of them in the National Library of Scotland, but in a manuscript identified about thirty years ago and presently in Dundee Uni versity Library, 1 is a small and succinct record kept by the author of significant events and moments in his life; it is entitled "MEMORIALLS." One aspect of this record puzzled Drummond's bibliographer and editor, R. H. MacDonald. This was Drummond's idiosyncratic use of the term "fatall." Drummond first employs this in the "Memorialls" to describe something that happened when he was twenty-five: "Tusday the 21 of Agust [sic] 1610 about Noone by the Death of my father began to be fatall to mee the 25 of my age" (Poems, p. -

Age of Chivalry

The Constraints Laws on Warfare in the Western World War Edited by Michael Howard, George J. Andreopoulos, and Mark R. Shulman Yale University Press New Haven and London Robert C . Stacey 3 The Age of Chivalry To those who lived during them, of course, the Middle Ages, as such, did not exist. If they lived in the middleof anything, most medieval people saw themselves as living between the Incarnation of God in Jesus and the end of time when He would come again; theirown age was thus a continuation of the era that began in the reign of Caesar Augustus with his decree that all the world should be taxed. The Age of Chivalry, however, some men of the time- mostly knights, the chevaliers, from whose name we derive the English word "chivalry"-would have recognized as an appropriate label for the years between roughly I 100 and 1500.Even the Age of Chivalry, however, began in Rome. In the chansons de geste and vernacular histories of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Hector, Alexander, Scipio, and Julius Caesar appear as the quintessential exemplars of ideal knighthood, while the late fourth or mid-fifth century Roman military writer Vcgetius remained far and away the most important single authority on the strategy and tactics of battle, his book On Military Matters (De re military passing in transla- tion as The Book of Chivalry from the thirteenth century on. The Middle Ages, then, began with Rome; and so must we if we are to study the laws of war as these developed during the Age of Chivalry. -

A Knights Own Book of Chivalry: Geoffroi De Charny Free

FREE A KNIGHTS OWN BOOK OF CHIVALRY: GEOFFROI DE CHARNY PDF Geoffroi de Charny,Richard W. Kaeuper,Elspeth Kennedy | 128 pages | 12 May 2005 | University of Pennsylvania Press | 9780812219098 | English | Pennsylvania, United States Geoffroi de Charny - Wikipedia Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Richard W. Kaeuper Introduction. Elspeth Kennedy Translator. On the great influence of a valiant lord: "The companions, who see that good warriors are honored by the great lords for their prowess, become more determined to attain this level of prowess. Read how an aspiring knight of the fourteenth century would conduct himself and learn what he would have needed to know when traveling, fighting, appearing in court, and engaging fellow knights. This is the most authentic and complete manual on the day-to-day life of the knight that has survived the centuries, and this edition contains a specially commissioned introduction from historian Richard W. Kaeuper that gives the history of both the book and its author, who, among his other achievements, was the original owner of the Shroud of Turin. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Original Title. Other Editions 3. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. -

A Knights Own Book of Chivalry: Geoffroi De Charny Free Download

A KNIGHTS OWN BOOK OF CHIVALRY: GEOFFROI DE CHARNY FREE DOWNLOAD Geoffroi de Charny,Richard W. Kaeuper,Elspeth Kennedy | 128 pages | 12 May 2005 | University of Pennsylvania Press | 9780812219098 | English | Pennsylvania, United States A Knight's Own Book of Chivalry Other Editions 3. As for the over bearing message of Christianity throughout the text it, it was written in 13th century France, of course it's going to be filled with overt religious tones - everyone was then. Beware the "holier-than-thou". Geoffroi also goes on to describe ball games as a women's sport that men have wrongly taken from them! Kaeuper A Knights Own Book of Chivalry: Geoffroi De Charny. Geoffroi's fortitude and devotion become apparent almost immediately and I couldn't help but admire him. Thus, the great lords in particular must be temperate in their eating habits, avoid gambling and greed, indulge only in honorable pastimes such as jousting and maintaining the company of ladies, keep any romantic liaisons secret, and—most importantly—only be found in the company of worthy men. He says nothing about spiritual counseling, community service, or politics whatsoever. Lists with This Book. A neat article. Geoffroi isn't much for games, but knows that young men will inevitably play them. Once, when he was captured by the English, Geoffroi's captor actually released him, trusting him to go back home to raise money for his own ransom which, as far as we can tell, Geoffroi actually did. Books A Knights Own Book of Chivalry: Geoffroi De Charny Geoffroi De Charny. -

The Downfall of Chivalry

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2019 The oD wnfall of Chivalry: Tudor Disregard for Medieval Courtly Literature Jessica G. Downie Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the European History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Downie, Jessica G., "The oD wnfall of Chivalry: Tudor Disregard for Medieval Courtly Literature" (2019). Honors Theses. 478. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/478 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. iii Acknowledgments I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Professor Jay Goodale, for guiding me through this process. You have challenged me in many ways to become a better historian and writer, and you have always been one of my biggest fans at Bucknell. Your continuous encouragement, support, and guidance have influenced me to become the student I am today. Thank you for making me love history even more and for sharing a similar taste in music. I promise that one day I will understand how to use a semi-colon properly. Thank you to my family for always supporting me with whatever I choose to do. Without you, I would not have had the courage to pursue my interests and take on the task of writing this thesis. Thank you for your endless love and support and for never allowing me to give up. -

First Series, 1883-1910 1 the Kingis Quair, Ed. W. W. Skeat 1884 2 The

First Series, 1883-1910 1 The Kingis Quair, ed. W. W. Skeat 1884 2 The Poems of William Dunbar I, ed. John Small 1893 3 The Court of Venus, by John Rolland. 1575, ed. Walter Gregor 1884 4 The Poems of William Dunbar II, ed. John Small 1893 5 Leslie’s Historie of Scotland I, ed. E.G. Cody 1888 6 Schir William Wallace I, ed. James Moir 1889 7 Schir William Wallace II, ed. James Moir 1889 8 Sir Tristrem, ed. G.P. McNeill 1886 9 The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie I, ed. James Cranstoun 1887 10 The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie II, ed. James Cranstoun 1887 11 The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie III, ed. James Cranstoun 1887 12 The Richt Vay to the Kingdome of Heuine by John Gau, ed. A.F. Mitchell 1888 13 Legends of the Saints I, ed. W.M. Metcalfe 1887 14 Leslie’s History of Scotland II, ed. E.G. Cody 1895 15 Niniane Winzet’s Works I, ed. J. King Hewison 1888 16 The Poems of William Dunbar III, ed. John Small, Introduction by Æ.J.G. Mackay 1893 17 Schir William Wallace III, ed. James Moir 1889 18 Legends of the Saints II, ed. W.M. Metcalfe 1888 19 Leslie’s History of Scotland III, ed. E.G. Cody 1895 20 Satirical Poems of the Time of the Reformation I, ed. James Cranstoun REPRINT 1889 21 The Poems of William Dunbar IV, ed. John Small 1893 22 Niniane Winzet’s Works II, ed. J. King Hewison 1890 23 Legends of the Saints III, ed.