Zagreb Baths in the Middle Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oligarchs, King and Local Society: Medieval Slavonia

Antun Nekić OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University CEU eTD Collection Budapest May2015 OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 by Antun Nekić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest Month YYYY OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 by Antun Nekić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. CEU eTD Collection ____________________________________________ External Reader Budapest Month YYYY OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 by Antun Nekić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Supervisor CEU eTD Collection Budapest Month YYYY I, the undersigned, Antun Nekić, candidate for the MA degree in Medieval Studies, declare herewith that the present thesis is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person’s or institution’s copyright. -

Hellozagreb5.Pdf

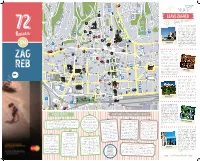

v ro e H s B o Šilobodov a u r a b a v h Put o h a r r t n e e o i k ć k v T T c e c a i a i c k Kozarčeve k Dvor. v v W W a a a Srebrnjak e l Stube l St. ć č Krležin Gvozd č i i s ć Gajdekova e k Vinogradska Ilirski e Vinkovićeva a v Č M j trg M l a a a Zamen. v č o e Kozarčeva ć k G stube o Zelengaj NovaVes m Vončinina v Zajčeva Weberova a Dubravkin Put r ić M e V v Mikloušić. Degen. Iv i B a Hercegovačka e k Istarska Zv k u ab on ov st. l on ar . ić iće Višnjica . e va v Šalata a Kuhačeva Franje Dursta Vladimira Nazora Kožarska Opatička Petrova ulica Novakova Demetrova Voćarska Višnjičke Ribnjak Voćarsko Domjanićeva stube naselje Voćarska Kaptol M. Slavenske Lobmay. Ivana Kukuljevića Zamenhoova Mletač. Radićeva T The closest and most charming Radnički Dol Posil. stube k v Kosirnikova a escape from Zagreb’s cityŠrapčeva noise e Jadranska stube Tuškanac l ć Tuškanac Opatovina č i i is Samobor - most joyful during v ć e e Bučarova Jurkovićeva J. Galjufa j j Markov v the famous Samobor Carnival i i BUS r r trg a Ivana Gorana Kovačića Visoka d d andJ. Gotovca widely known for the cream Bosanska Kamenita n n Buntićeva Matoševa A A Park cake called kremšnita. Maybe Jezuitski P Pantovčak Ribnjak Kamaufova you will have to wait in line to a trg v Streljačka Petrova ulica get it - many people arrive on l Vončinina i Jorgov. -

Sweet September

MARK YOUR MAPS WITH THE BEST OF MARKETS * Agram German exonym its Austrian by outside Croatia known commonly more was Zagreb LIMITED EDITION INSTAGRAM* FREE COPY Zagreb in full color No. 06 SEPTEMBER ast month, Zagreb was abruptly left without Dolac. 2015. LFor one week, stalls and vendors migrated to Ban Jelačić Square, only to move back to their original place, but now repaved, refurbished and in full color again. The Z ‘misplaced’ Dolac was a unique opportunity to be remind- on Facebook ed of what things were like half a century ago. This month 64-second kiss there is another time-travel experience on Jelačić Square: on the world’s Vintage Festival in the Johann Franck cafe, taking us shortest funic- back to the 50s and 60s. Read more about it in this issue... ular ride The world’s shortest funicular was steam-powered Talkabout until 1934. The lower stop on Croatia Tomićeva Street GRIČ-BIT IS BACK! connects with the upper stop on The fifth edition of the the Strossmayer best street festival kicks promenade, off on the first day of in front of the ANJA MUTIĆ fall, joining forces with Lotršćak Tower. Author of Lonely Planet Croatia, writes for New the ‘At the Upper Town’ As the Zagreb York Magazine and The Washington Post. Follow her at @everthenomad initiative and showcas- oldest means of public transport, ing Device_art work- the funicular shops and exhibitions began operating Sweet hosted by Space Festival only a year and the Klovićevi Dvori before the horse- gallery. All this topped drawn tram. -

Zagreb Winter 2016/2017

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels Zagreb Winter 2016/2017 Trešnjevka Where wild cherries once grew Go Gourmet A Croatian feast Shopping Cheat Sheet Find your unique item N°86 - complimentary copy zagreb.inyourpocket.com Festive December Contents in Ljubljana ESSENTIAL CITY G UIDES Foreword 4 Sightseeing 46 A word of welcome Snap, camera, action Arrival & Getting Around 6 Zagreb Pulse 53 We unravel the A to Z of travel City people, city trends Zagreb Basics 12 Shopping 55 All the things you need to know about Zagreb Ready for a shopping spree Trešnjevka 13 Hotels 61 A city district with buzz The true meaning of “Do not disturb” Culture & Events 16 List of Small Features Let’s fill up that social calendar of yours Advent in Zagreb 24 Foodie’s Guide 34 Go Gourmet 26 Festive Lights Switch-on Event City Centre Shopping 59 Ćevap or tofu!? Both! 25. Nov. at 17:15 / Prešernov trg Winter’s Hot Shopping List 60 Restaurants 35 Maps & Index Festive Fair Breakfast, lunch or dinner? You pick... from 25. Nov. / Breg, Cankarjevo nabrežje, Prešernov in Kongresni trg Street Register 63 Coffee & Cakes 41 Transport Map 63 What a pleasure City Centre Map 64-65 St. Nicholas Procession City Map 66 5. Dec. at 17:00 / Krekov trg, Mestni trg, Prešernov trg Nightlife 43 Bop ‘till you drop Street Theatre 16. - 20. Dec. at 19:00 / Park Zvezda Traditional Christmas Concert 24. Dec. at 17:00 / in front of the Town Hall Grandpa Frost Proccesions 26. - 30. Dec. at 17:00 / Old Town New Year’s Eve Celebrations for Children 31. -

Investicijski Potencijali Hrvatske

KONFERENCIJA INVESTICIJSKI POTENCIJALI HRVATSKE Srijeda, 23. travnja 2014. Kristalna dvorana Hotel Westin Zagreb ...About Croatia... ...o Hrvatskoj... Republika Hrvatska sredn-joeuropska The Republic of Croatia is a Central ...o Hrvatskoj... 3 ...o Hrvatskoj... je i mediteran-ska zemlja. Doseljenjem European and Medi-terranean county. na današnji hrvatski prostor u 7. The Croats settled on the today’s Tomislav Karamarko 6 Tomislav Karamarko stoljeću, na prostor od Jadranskog Croatian territory in the 7th century, Predsjednik HDZ-a President of HDZ mora do Drave i Dunava, Hrvati su u in the area between the Adri-atic Sea on Srećko Prusina 10 Srećko Prusina novoj domovini asimilirali stečevine one side, and the Drava and the Danube rimske, helenske i bizantske civilizacije, on the other. Croats assimilated Ro- Klaus-Peter Willsch 12 Klaus-Peter Willsch očuvavši svoj jezik i zajedništvo. Već od man, Hellenistic and Byzantine heritage ranog srednjeg vijeka, u doba narodne in their new home-land, preserving prof.dr.sc. Krunoslav Zmaić 14 Krunoslav Zmaić, PhD dinastije Trpimirovića, kao jedna od their language and unity. Ever since najstarijih europskih država, Hrvatska the early Middle Ages and the times trajno pripada katoličkom i kršćanskom of Trpimirović Dynasty, Croatia has, as Marija Tufekčić 17 Marija Tufekčić za-padu. Tijekom tog vremena Hrvati one of the oldest Eu-ropean countries, su, uz standarni latin-ski jezik u permanently belonged to catholic and Zdravko Krmek 18 Zdravko Krmek diplomatičkim is-pravama, koristili i Chris-tian West. In that time Croats hrvatski, pisan uglatom glagoljicom, used standard Latin language in Zlatko Rogožar 20 Zlatko Rogožar kroz koju se sačuvao ne samo jezik, diplomatic documents, but Croatian već i drevna pučka duhovnost. -

EN-Zagreb-2307.Pdf

A Welcome to Zagreb As you set out to take a tour round Zagreb, determined to see its highlights, you’ll find that you’ll end up rather enjoying it. Sitting at one of its Viennese- style cafés, strolling leisurely around its streets and promenading through its parks, it’s like you’re starting out on a love affair with this city and its people. And pretty soon you’ll know that this is love in its early stage, the kind that only grows stronger in time. The cosmopolitan buzz of Zagreb will soon strike you. Everything is accessible on foot – from your hotel to the theatre, wandering around the old Upper Town or through the bustling streets of the more modern Lower Town, which has not lost an ounce of its charm despite the eternal march of time. Venture out and let the moment take hold. There is something special about the rustle of leaves as you stroll through the autumn colours of downtown Zrinjevac Park. There is magic in the reflections of the gas lanterns in the Upper Town, as the songs of the street performers evoke their own emotions with their distinctive sound. As night falls, everything becomes soft and subdued; the twinkle of candles in the cathedral and at the mystical Stone Gate; the cafés beckoning you in the twilight with their warm hues. Zagreb is special. It is a long-running tale that allows you room to write your own chapters with your own impressions, something for you to add to the story. Quite simply, Zagreb has a soul. -

Gold Edition.Pdf

PUBLISHER Darrer d.o.o. Dear Reader, Welcome to Zagreb, one of the best shopping destinations when it comes to high quality clothing. Under the brand name Hello COMPANY OFFICE Zagreb, experienced in promoting only the best-off tourist offer, we Hello Zagreb map & guide Illica 49/III present you the luxury shopping guide Gold edition. Designed 10000 Zagreb to refine the selection and enrich your experience, it will lead you to FB: Hello Zagreb W: www.hellocroatia.eu the finest offer that will surely please your exquisite taste. All the EDITORIAL exclusive stores you need are right in the middle of charming and picturesque downtown, so small you can easily walk around the Editor: Anita Tutić T: +385 91 3774 358 key points. While taking time off from the shopping tour, and E: [email protected] delighting yourself with rich coffee and tasty bites, be entertained Assistant Editor: Korana Gjalski Filipović with the interesting details about Zagreb in our timeline through T: +385 91 7345 693 E: [email protected] the centuries. Meet some of the richest and most influential Design: Nika Svilar women from the history of Zagreb, their fashion trends and rules City map: Štef d.o.o. from the 17th till the 20th century, explore the glamorous parties Photography: of the elite class, and learn more about the enjoyable lifestyle in Zvonimir Milčec, “Galantni Zagreb” Zagreb, maintained with style until today. Gjuro Szabo, “Stari Zagreb” “Svijet”, 1927.-1929. Yours Hello Zagreb RESIDENCE – SHOPPING – GARAGE Downtown Zagreb Trg Petra Preradovića 6 T: +385 1 4874 370 www.centarcvjetni.hr Vlaška 125, Zagreb T: +385 1 6447 413 Avenija Dubrovnik 16, Zagreb Avenue Mall T: +385 1 6593 076 www.argentum.hr Masarykova 7, Zagreb T: +385 1 4920 705 Nova Ves 17, Zagreb Kaptol Centar T: +385 1 4667 591 www.apriori-fashion.hr Trg Petra Preradovića 6, Zagreb Centar Cvjetni T: +385 1 5630 150 Jankomir 33, Zagreb City Center one West T: +385 1 5630 157 The beginning of fashion in Zagreb, followed only by a thin layer of the high society. -

26Th SESSION of EIFAC Zagreb, Croatia, 17-20 May 2010 Hotel

26th SESSION OF EIFAC Zagreb, Croatia, 17-20 May 2010 Hotel International 1 Miramarska 24, Zagreb 10000, Croatia, Phone: (+385)(1) 6108800 (http://www.hotel-international.hr/?l=en) GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT ZAGREB Welcome to Zagreb, the capital city of the Republic of Croatia. Zagreb is an old Central European city. For centuries it has been a focal point of culture and science, and now of commerce and industry as well. It lies on the intersection of important routes between the Adriatic coast and Central Europe. When the Croatian people achieved their independence in 1991, Zagreb became a capital - a political and administrative centre for the Republic of Croatia. Zagreb is also the hub of the business, academic, cultural, artistic and sporting worlds in Croatia. Many famed scientists, artists and athletes come from the city, or work in it. Zagreb can offer its visitors the Baroque atmosphere of the Upper Town, picturesque open-air markets, diverse shopping facilities, an abundant selection of crafts and a choice vernacular cuisine. Zagreb is a city of green parks and walks, with many places to visit in the beautiful surroundings. The city entered into the third millennium with a population of one million. In spite of the rapid development of the economy and transportation, it has retained its charm, and a relaxed feeling that makes it a genuinely human city. 1 The booking form for this hotel is also posted on the website together with all the other meeting information. Other hotels can for example be booked through the Zagreb Tourist Board http://www.zagreb-touristinfo.hr/?id=49&l=e&nav=nav4 Location: northern Croatia, on the Sava River, 170 km from the Adriatic Sea 45° 10' N, 15° 30' E situated 122 m above sea level Time: Central-european time (GMT+1) Climate and Weather: continental climate average summer temperature: 20° C average winter temperature: 1° C Population: 779 145 (2001) Surface area: 650 sq. -

Zagreb Winter 2019-2020

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Zagreb Winter 2019-2020 COOL-TURE The best of culture and events this winter N°98 - complimentary copy zagreb.inyourpocket.com Contents ESSENTIAL CIT Y GUIDES Foreword 4 Zagorje Day Trip 51 A zesty editorial to unfold Beautiful countryside Cool-ture 6 Shopping 52 The best of culture and events this winter Priceless places and buys Restaurants 32 Arrival & Getting Around 60 We give you the bread ‘n’ butter of where to eat SOS! Have no fear, ZIYP is here Coffee & Cakes 43 Maps “How’s that sweet tooth?” Street Register 63 City Centre Map 64-65 Nightlife 46 City Map 66 Are you ready to party? Sightseeing 49 Discover what we‘ve uncovered Bowlers, Photo by Ivo Kirin, Prigorje Museum Archives facebook.com/ZagrebInYourPocket Winter 2019-2020 3 Foreword Winter is well and truly here and even though the days are shorter and the nights both longer and colder, there is plenty of room for optimism and cheer and we will give you a whole load of events and reasons to beg that receptionist back at the hotel/hostel to prolong your stay for another day or week! But the real season by far is Advent, the lead up to Christmas where Zagrebians come out in force and Publisher Plava Ponistra d.o.o., Zagreb devour mulled wine, grilled gourmet sausages, hot round ISSN 1333-2732 doughnuts, and many other culinary delights. And since Advent is in full swing, we have a resounding wrap up of Company Office & Accounts Višnja Arambašić what to do and see. -

ZAGREB a Brief History of Zagreb

THE CITY WITH A MILLION HEARTS ZAGREB A brief history of Zagreb Zagreb’s history dates back to the Roman times when the urban settlement of Andautonia, inhabited the location of modern Ščitarjevo. The name Zagreb first came into existence in 1904 with the founding of the Zagreb bishopric of Kaptol. In 1242, it became a free royal town and in 1851 it had its own Mayor, Janko Kamauf. In 1945, Zagreb was declared the capital of Croatia. Today's Zagreb has grown out of two medieval settlements that for centuries developed on neighbouring hills. The first written mention of the city dates from 1094, when a diocese was founded on Kaptol, while in 1242, neighbouring Gradec was proclaimed a free and royal city. Both the settlements were surrounded by high walls and towers, remains of which are still preserved. During the Turkish onslaughts on Europe, between the 14th and 18th centuries, Zagreb was an important border fortress. The Baroque reconstruction of the city in the 17th and 18th centuries changed the appearance of the city. The old wooden houses were demolished, opulent palaces, monasteries and churches were built. The many trade fairs, the revenues from landed estates and the offerings of the many craft workshops greatly contributed to the wealth of the city. Affluent aristocratic families, royal officials, church dignitaries and rich traders from the whole of Europe moved into the city. Schools and hospitals were opened, and the manners of European capitals were adopted. The city outgrew its medieval borders and spread to the lowlands. The first parks and country houses were built. -

SIEF Congresses

Zagreb 12th Congress, 21-25 June 2015 Timetable Sun June 21 Mon June 22 Tue June 23 Wed June 24 Thu June 25 08:45- 09:45 Keynote 2 Keynote 3 Keynote 4 09:45-10:00 Getting from Keynote to main venue 10:00-10:30 Refreshments Refreshments Refreshments 10:30-12:00 Panel session 1 Panel session 4 Panel session 7 12:00-14:00 Lunch Lunch Lunch 14:00-15:30 Panel session 2 Panel session 5 Panel session 8 Excursions 15:30-16:00 Refreshments Refreshments Refreshments Registration 16:00-17:30 Panel session 3 Panel session 6 Panel session 9 17:30-17:50 Break Break Break Young Scholar Working group 17:50-18:50 Prize & meetings Closing Opening and presentation roundtable Keynote 1 (ends 19:20) 18:50-19:00 (start 18:00) Break Break 19:00-19.30 YS Wine Mixer Journal launch General Assembly 19:30-20:00 Coord meeting of Welcome reception Uni Deps 20:00-21:00 Banquet (starts 20:30) 21:00-22:30 22:30-00:00 Final Party SIEF2015 Utopias, Realities, Heritages: Ethnographies for the 21st Century 12th Congress of Société Internationale d’Ethnologie et de Folklore (SIEF) Department of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb 21-25 June 2015 Acknowledgements SIEF Board: Pertti Anttonen, Jasna Čapo, Tine Damsholt, Laurent Fournier, Valdimar Hafstein, Peter Jan Margry, Arzu Öztürkmen, Clara Saraiva, Monique Scheer SIEF2015 Congress convenors: Jasna Čapo and Nevena Škrbić Alempijević SIEF2015 Scientific Committee:Jasna Čapo, Laurent Fournier, Valdimar Hafstein, Peter Jan Margry, Sanja Potkonjak, Clara Saraiva, -

Analysis of the Touristic Valorization of Maksimir Park in Zagreb (Croatia)

TURIZAM Volume 16, Issue 3 88-101 (2012) Analysis of the Touristic Valorization of Maksimir Park in Zagreb (Croatia) Nika Dolenc*, Renata Grbac Žiković**, Rade Knežević*** Received: December 2011 | Accepted: April 2012 Abstract The modern pace of life imposes new needs and demands of the tourist market as well as the need for rest and recreation in areas of preserved nature. Maksimir Park dates from the 19th century, and since 1964, it has been protected as a monument of park architecture. Today, the park is the space for recrea- tion and relaxation with cultural monuments and natural heritage. They make a strong and attractive potential factor that has been underused in the tourist offer of the City of Zagreb. The paper examines the attractiveness of the park for visitors, whilst also making the comparison with some of the parks of London (Hyde Park, Regent’s Park, Kew Gardens). The main goal of this paper is to analyze the exist- ing resources of the park and to identify their weaknesses in order to complement and enhance the offer of the park as a tourist attraction. The methodology is based on the analysis of material of the origin and the development of Maksimir Park, the evaluation survey conducted in 2009 and 2010 in the park area (case study) and SWOT analysis of the significant resource for tourism development of the park. The results show that Maksimir Park contains many resources, but they are not recognized as a tour- ist attraction of Zagreb. Tourist services in the park are not harmonized with visitors’ needs and should be complemented with traditional and cultural events, better cuisine, education about resources of the park and improved range of activities throughout the year.