Analysis of the Touristic Valorization of Maksimir Park in Zagreb (Croatia)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grad Zagreb (01)

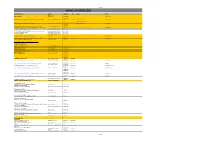

ADRESARI GRAD ZAGREB (01) NAZIV INSTITUCIJE ADRESA TELEFON FAX E-MAIL WWW Trg S. Radića 1 POGLAVARSTVO 10 000 Zagreb 01 611 1111 www.zagreb.hr 01 610 1111 GRADSKI URED ZA STRATEGIJSKO PLANIRANJE I RAZVOJ GRADA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/II 01 610 1575 610-1292 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr [email protected] 01 658 5555 01 658 5609 GRADSKI URED ZA POLJOPRIVREDU I ŠUMARSTVO Zagreb, Avenija Dubrovnik 12/IV 01 658 5600 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr 01 610 1111 01 610 1169 GRADSKI URED ZA PROSTORNO UREĐENJE, ZAŠTITU OKOLIŠA, Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 610 1168 IZGRADNJU GRADA, GRADITELJSTVO, KOMUNALNE POSLOVE I PROMET 01 610 1560 01 610 1173 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr 1.ODJEL KOMUNALNOG REDARSTVA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 06 111 2.DEŽURNI KOMUNALNI REDAR (svaki dan i vikendom od 08,00-20,00 sati) Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 01 566 3. ODJEL ZA UREĐENJE GRADA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 01 184 4. ODJEL ZA PROMET Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 01 111 Zagreb, Ulica Republike Austrije 01 610 1850 GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA PROSTORNO UREĐENJE 18/prizemlje 01 610 1840 01 610 1881 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr 01 485 1444 GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA ZAŠTITU SPOMENIKA KULTURE I PRIRODE Zagreb, Kuševićeva 2/II 01 610 1970 01 610 1896 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA JAVNO ZDRAVSTVO Zagreb, Mirogojska 16 01 469 6111 INSPEKCIJSKE SLUŽBE-PODRUČNE JEDINICE ZAGREB: 1)GRAĐEVINSKA INSPEKCIJA 2)URBANISTIČKA INSPEKCIJA 3)VODOPRAVNA INSPEKCIJA 4)INSPEKCIJA ZAŠTITE OKOLIŠA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 610 1111 SANITARNA INSPEKCIJA Zagreb, Šubićeva 38 01 658 5333 ŠUMARSKA INSPEKCIJA Zagreb, Zapoljska 1 01 610 0235 RUDARSKA INSPEKCIJA Zagreb, Ul Grada Vukovara 78 01 610 0223 VETERINARSKO HIGIJENSKI SERVIS Zagreb, Heinzelova 6 01 244 1363 HRVATSKE ŠUME UPRAVA ŠUMA ZAGREB Zagreb, Kosirnikova 37b 01 376 8548 01 6503 111 01 6503 154 01 6503 152 01 6503 153 01 ZAGREBAČKI HOLDING d.o.o. -

Oligarchs, King and Local Society: Medieval Slavonia

Antun Nekić OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University CEU eTD Collection Budapest May2015 OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 by Antun Nekić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest Month YYYY OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 by Antun Nekić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. CEU eTD Collection ____________________________________________ External Reader Budapest Month YYYY OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 by Antun Nekić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Supervisor CEU eTD Collection Budapest Month YYYY I, the undersigned, Antun Nekić, candidate for the MA degree in Medieval Studies, declare herewith that the present thesis is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person’s or institution’s copyright. -

Hellozagreb5.Pdf

v ro e H s B o Šilobodov a u r a b a v h Put o h a r r t n e e o i k ć k v T T c e c a i a i c k Kozarčeve k Dvor. v v W W a a a Srebrnjak e l Stube l St. ć č Krležin Gvozd č i i s ć Gajdekova e k Vinogradska Ilirski e Vinkovićeva a v Č M j trg M l a a a Zamen. v č o e Kozarčeva ć k G stube o Zelengaj NovaVes m Vončinina v Zajčeva Weberova a Dubravkin Put r ić M e V v Mikloušić. Degen. Iv i B a Hercegovačka e k Istarska Zv k u ab on ov st. l on ar . ić iće Višnjica . e va v Šalata a Kuhačeva Franje Dursta Vladimira Nazora Kožarska Opatička Petrova ulica Novakova Demetrova Voćarska Višnjičke Ribnjak Voćarsko Domjanićeva stube naselje Voćarska Kaptol M. Slavenske Lobmay. Ivana Kukuljevića Zamenhoova Mletač. Radićeva T The closest and most charming Radnički Dol Posil. stube k v Kosirnikova a escape from Zagreb’s cityŠrapčeva noise e Jadranska stube Tuškanac l ć Tuškanac Opatovina č i i is Samobor - most joyful during v ć e e Bučarova Jurkovićeva J. Galjufa j j Markov v the famous Samobor Carnival i i BUS r r trg a Ivana Gorana Kovačića Visoka d d andJ. Gotovca widely known for the cream Bosanska Kamenita n n Buntićeva Matoševa A A Park cake called kremšnita. Maybe Jezuitski P Pantovčak Ribnjak Kamaufova you will have to wait in line to a trg v Streljačka Petrova ulica get it - many people arrive on l Vončinina i Jorgov. -

15:30 Registration of the Participants 16:00 – 17:00 Opening Address Jadranka Zarkovic-Pecenkovic, Director, Education And

16th Conference Teaching and Learning about the Holocaust and the Prevention of Crimes against Humanity Pula, 29th January – 1st February 2019 DRAFT PROGRAMME Tuesday, 29th January 2019, Hotel Pula, Sisplac 31, 52 100 Pula 15:30 Registration of the participants Opening Address Jadranka Zarkovic-Pecenkovic, Director, Education and Teacher Training Agency (Deputy) Mayor of the City of Pula (tbc) (Deputy) County Prefect of the Istarska County (tbc) 16:00 – 17:00 H. E. Ilan Mor, the Ambassador to Croatia of the State of Israel (tbc) H. E. Corrine/Philippe Meunier, the Ambassadors to Croatia of French Republic (tbc) (Assistant) Minister of Science and Education (tbc) (Envoy) President of the Republic of Croatia (tbc) 17:00 – 18:00 The Holocaust in Europe; lecture Tal Brutmann, PhD, Mémorial de la Shoah, France The Holocaust in the Independent State of Croatia; lecture 18:00 – 19:00 Ivo Goldstein, PhD, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb 19:00 Dinner Wednesday, 30th January 2019, Hotel Pula, Sisplac 31, 52 100 Pula Dealing with Controversial Issues in the Classroom; lecture 08:30 – 09:15 Charlot Cassar, Zabar Primary school B, Principal, Malta Group 1 – From the Arrest to the Return: The Plight of Istrian Inmates in the Holocaust – 09:15 – 10:45 Video Testimonies; workshop Igor Jovanović, Veli Vrh Primary School i Igor Šaponja, School of Economics Pula Group 2 – Controversial Issues as Learning Opportunities; workshop 09:15 – 10:45 Charlot Cassar, Zabar Primary school B, Principal, Malta 10:45 – 11:00 Break Group -

Sweet September

MARK YOUR MAPS WITH THE BEST OF MARKETS * Agram German exonym its Austrian by outside Croatia known commonly more was Zagreb LIMITED EDITION INSTAGRAM* FREE COPY Zagreb in full color No. 06 SEPTEMBER ast month, Zagreb was abruptly left without Dolac. 2015. LFor one week, stalls and vendors migrated to Ban Jelačić Square, only to move back to their original place, but now repaved, refurbished and in full color again. The Z ‘misplaced’ Dolac was a unique opportunity to be remind- on Facebook ed of what things were like half a century ago. This month 64-second kiss there is another time-travel experience on Jelačić Square: on the world’s Vintage Festival in the Johann Franck cafe, taking us shortest funic- back to the 50s and 60s. Read more about it in this issue... ular ride The world’s shortest funicular was steam-powered Talkabout until 1934. The lower stop on Croatia Tomićeva Street GRIČ-BIT IS BACK! connects with the upper stop on The fifth edition of the the Strossmayer best street festival kicks promenade, off on the first day of in front of the ANJA MUTIĆ fall, joining forces with Lotršćak Tower. Author of Lonely Planet Croatia, writes for New the ‘At the Upper Town’ As the Zagreb York Magazine and The Washington Post. Follow her at @everthenomad initiative and showcas- oldest means of public transport, ing Device_art work- the funicular shops and exhibitions began operating Sweet hosted by Space Festival only a year and the Klovićevi Dvori before the horse- gallery. All this topped drawn tram. -

Guide for Expatriates Zagreb

Guide for expatriates Zagreb Update: 25/05/2013 © EasyExpat.com Zagreb, Croatia Table of Contents About us 4 Finding Accommodation, 49 Flatsharing, Hostels Map 5 Rent house or flat 50 Region 5 Buy house or flat 53 City View 6 Hotels and Bed and Breakfast 57 Neighbourhood 7 At Work 58 Street View 8 Social Security 59 Overview 9 Work Usage 60 Geography 10 Pension plans 62 History 13 Benefits package 64 Politics 16 Tax system 65 Economy 18 Unemployment Benefits 66 Find a Job 20 Moving in 68 How to look for work 21 Mail, Post office 69 Volunteer abroad, Gap year 26 Gas, Electricity, Water 69 Summer, seasonal and short 28 term jobs Landline phone 71 Internship abroad 31 TV & Internet 73 Au Pair 32 Education 77 Departure 35 School system 78 Preparing for your move 36 International Schools 81 Customs and import 37 Courses for Adults and 83 Evening Class Passport, Visa & Permits 40 Language courses 84 International Removal 44 Companies Erasmus 85 Accommodation 48 Healthcare 89 2 - Guide for expats in Zagreb Zagreb, Croatia How to find a General 90 Practitioner, doctor, physician Medicines, Hospitals 91 International healthcare, 92 medical insurance Practical Life 94 Bank services 95 Shopping 96 Mobile Phone 99 Transport 100 Childcare, Babysitting 104 Entertainment 107 Pubs, Cafes and Restaurants 108 Cinema, Nightclubs 112 Theatre, Opera, Museum 114 Sport and Activities 116 Tourism and Sightseeing 118 Public Services 123 List of consulates 124 Emergency services 127 Return 129 Before going back 130 Credit & References 131 Guide for expats in Zagreb - 3 Zagreb, Croatia About us Easyexpat.com is edited by dotExpat Ltd, a Private Company. -

Zagreb Winter 2016/2017

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels Zagreb Winter 2016/2017 Trešnjevka Where wild cherries once grew Go Gourmet A Croatian feast Shopping Cheat Sheet Find your unique item N°86 - complimentary copy zagreb.inyourpocket.com Festive December Contents in Ljubljana ESSENTIAL CITY G UIDES Foreword 4 Sightseeing 46 A word of welcome Snap, camera, action Arrival & Getting Around 6 Zagreb Pulse 53 We unravel the A to Z of travel City people, city trends Zagreb Basics 12 Shopping 55 All the things you need to know about Zagreb Ready for a shopping spree Trešnjevka 13 Hotels 61 A city district with buzz The true meaning of “Do not disturb” Culture & Events 16 List of Small Features Let’s fill up that social calendar of yours Advent in Zagreb 24 Foodie’s Guide 34 Go Gourmet 26 Festive Lights Switch-on Event City Centre Shopping 59 Ćevap or tofu!? Both! 25. Nov. at 17:15 / Prešernov trg Winter’s Hot Shopping List 60 Restaurants 35 Maps & Index Festive Fair Breakfast, lunch or dinner? You pick... from 25. Nov. / Breg, Cankarjevo nabrežje, Prešernov in Kongresni trg Street Register 63 Coffee & Cakes 41 Transport Map 63 What a pleasure City Centre Map 64-65 St. Nicholas Procession City Map 66 5. Dec. at 17:00 / Krekov trg, Mestni trg, Prešernov trg Nightlife 43 Bop ‘till you drop Street Theatre 16. - 20. Dec. at 19:00 / Park Zvezda Traditional Christmas Concert 24. Dec. at 17:00 / in front of the Town Hall Grandpa Frost Proccesions 26. - 30. Dec. at 17:00 / Old Town New Year’s Eve Celebrations for Children 31. -

University of Zagreb Contents

university of zagreb contents university of zagreb introduction rector’s welcome address Dear student, Dear student, We are happy to see that you have chosen the University of Zagreb for your studies or are On behalf of the University of Zagreb, its staff and students, I wish you a warm welcome to the about to do so. University and City of Zagreb. The present Guide should help you in your first contacts with Croatia and the City and University The University of Zagreb, founded in 1669, is the oldest one in the country and particularly rich of Zagreb. It includes information about studying at the University of Zagreb as well as practical in tradition. As a comprehensive Central European university, it offers research and education advice, which should provide answers to questions about accommodation, transport, and in all scientific fields and a broad spectrum of courses at all study levels, from undergraduate administrative steps. We hope it will make it easier for you to find your place among many to postgraduate. students in Zagreb. With 30 Faculties, 3 Art Academies, and the University Department for Croatian Studies, the University is the flagship educational institution in the country, a place where more than 7,500 Throughout your study period at the University of Zagreb, our team will be available to help teachers and 77,000 students develop knowledge and acquire skills. The University excels not you so that your experience is as successful as possible, both from an academic and personal only in teaching, but also in research, contributing with over 40 percent of the yearly research point of view. -

University of Zagreb

University of Zagreb University of Zagreb's Internationalisation Strategy 2014-2025 May 16, 2014 version Task group in charge of developing University of Zagreb's Internationalisation Strategy: 1. Zdenko Kovač, Prof. PhD 2. Melita Kovačević, Prof. PhD 3. Blaženka Divjak, Prof. PhD 4. Branka Roščić, PhD 5. Hrvoje Šikić, Prof. PhD 6. Duška Čurić, Prof. PhD 7. Lidija Bach-Rojecky, Assistant Professor, PhD 8. Jelena Filipović-Grčić, Prof. PhD 9. Marijan Šušnjar, Prof. PhD 10. Branka Galić, Prof. PhD 11. Nebojša Blanuša, Prof. PhD 12. Marko Rogošić, Prof. PhD 13. Nenad Puhovski, Full Professor (excused himself on account of illness) 14. Tamara Nikšić, Prof. PhD Administrative and professional assistance from the Rectorate's administrative and professional service: Dora Gelo, Mag. iur. 1 INTRODUCTION Vision University of Zagreb's international activities are incentives to creativity, high quality science, application and updating of teaching processes. They are a key aspect of the University activities which, through international research activities as well as student, teacher and researcher mobility, contributes to achieving excellence in all areas of sciences and arts, study programmes and studying at the University, and the international and particularly regional visibility and recognisability of the University. The University's mission in the area of international cooperation Research, according to international standards of quality, is the best form of university teaching. Apart from learning, the university process includes teaching and raising new generations and the application of knowledge and skills as an indivisible and interdependent process. In that union the University of Zagreb sees a powerful lever for realizing the identity, creative power and development potential – both of the individuals as global citizens and of the institution itself as an international agent. -

Investicijski Potencijali Hrvatske

KONFERENCIJA INVESTICIJSKI POTENCIJALI HRVATSKE Srijeda, 23. travnja 2014. Kristalna dvorana Hotel Westin Zagreb ...About Croatia... ...o Hrvatskoj... Republika Hrvatska sredn-joeuropska The Republic of Croatia is a Central ...o Hrvatskoj... 3 ...o Hrvatskoj... je i mediteran-ska zemlja. Doseljenjem European and Medi-terranean county. na današnji hrvatski prostor u 7. The Croats settled on the today’s Tomislav Karamarko 6 Tomislav Karamarko stoljeću, na prostor od Jadranskog Croatian territory in the 7th century, Predsjednik HDZ-a President of HDZ mora do Drave i Dunava, Hrvati su u in the area between the Adri-atic Sea on Srećko Prusina 10 Srećko Prusina novoj domovini asimilirali stečevine one side, and the Drava and the Danube rimske, helenske i bizantske civilizacije, on the other. Croats assimilated Ro- Klaus-Peter Willsch 12 Klaus-Peter Willsch očuvavši svoj jezik i zajedništvo. Već od man, Hellenistic and Byzantine heritage ranog srednjeg vijeka, u doba narodne in their new home-land, preserving prof.dr.sc. Krunoslav Zmaić 14 Krunoslav Zmaić, PhD dinastije Trpimirovića, kao jedna od their language and unity. Ever since najstarijih europskih država, Hrvatska the early Middle Ages and the times trajno pripada katoličkom i kršćanskom of Trpimirović Dynasty, Croatia has, as Marija Tufekčić 17 Marija Tufekčić za-padu. Tijekom tog vremena Hrvati one of the oldest Eu-ropean countries, su, uz standarni latin-ski jezik u permanently belonged to catholic and Zdravko Krmek 18 Zdravko Krmek diplomatičkim is-pravama, koristili i Chris-tian West. In that time Croats hrvatski, pisan uglatom glagoljicom, used standard Latin language in Zlatko Rogožar 20 Zlatko Rogožar kroz koju se sačuvao ne samo jezik, diplomatic documents, but Croatian već i drevna pučka duhovnost. -

Zagrebact HOLDING D.O.O., Zagreb

ZAGREBaCT HOLDING d.o.o., Zagreb Unconsolidated fi nancial statements For the year ended 31 December 2012 Together with Independent Auditor's Reporl 一一 〕 Contents 〕 P 一 〕 a9 e for the unconsolidated financial statements 1´ lndependent Auditor's Report 2‐ 4 〕 Unconsolidated Statement of Comprehensive lncome 5 一 一 Unconsolidated statement of financial position 6-7 Unconsolidated statement of changes in shareholders' equity 8 Unconsolidated statement of cash flows 9-10 一 〕 Notes to the unconsolidated financial statements 11-114 】 . 〕一 ) ・】 ヽ 一 ^ 一 、 一 二 一 一 十 一 ( 一 Responsibility for the unconsolidated financial statements Pursuant to the applicable Accounting Act of the Republic of Croatia, the Management Board is responsible for ensuring that financial statements are prepared for each financial year in accordance with lnternational Financial Reporting Standards ("the lFRSs") as published by the lnternational Accounting Standards Board ("|ASB"), which give a true and fair view of the financial position and results of operations of the Company for that period. After making enquiries, the Management Board has a reasonable expectation that the Company has adequate resources to continue in operational existence for the foreseeable future. For this reason, the Management Board continues to adopt the going concern basis in preparing the unconsolidated financial statements. ln preparing those unconsolidated financial statements, the responsibilities of the Management Board of Company include ensuring that: . suitable accounting policies are selected and then applied consistently; . judgments and estimates are reasonable and prudent; . applicable accounting standards are followed, subject to any material departures disclosed and explained in the consolidated financial statements; and . the financial statements are prepared on the going concern basis unless it is inappropriate to presume that the Company will continue in business. -

Egypt in Croatia Croatian Fascination with Ancient Egypt from Antiquity to Modern Times

Egypt in Croatia Croatian fascination with ancient Egypt from antiquity to modern times Mladen Tomorad, Sanda Kočevar, Zorana Jurić Šabić, Sabina Kaštelančić, Marina Kovač, Marina Bagarić, Vanja Brdar Mustapić and Vesna Lovrić Plantić edited by Mladen Tomorad Archaeopress Egyptology 24 Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-339-3 ISBN 978-1-78969-340-9 (e-Pdf) © Authors and Archaeopress 2019 Cover: Black granite sphinx. In situ, peristyle of Diocletian’s Palace, Split. © Mladen Tomorad. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Severn, Gloucester This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents Preface ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������xiii Chapter I: Ancient Egyptian Culture in Croatia in Antiquity Early Penetration of Ancient Egyptian Artefacts and Aegyptiaca (7th–1st Centuries BCE) ..................................1 Mladen Tomorad Diffusion of Ancient Egyptian Cults in Istria and Illyricum (Late 1st – 4th Centuries BCE) ................................15 Mladen Tomorad Possible Sanctuaries of Isaic Cults in Croatia ...................................................................................................................26