Zelena Potkova) Irena Kraševac

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Group Portrait with an Austrian Marshal, an Honorary Citizen of Ljubljana

A GROUP PORTRAIT WITH AN AUSTRIAN MARSHAL, AN HONORARY CITIZEN OF LJUBLJANA BOŽIDAR JEZERNIK This article deals with two public monuments in Ljubljana Članek obravnava dva spomenika v Ljubljani, posvečena dedicated to Field Marshal Radetzky, who lived in Ljubljana feldmaršalu Radeckemu, ki je v mestu živel med letoma 1852 between 1852 and 1856 and was made an honorary citizen of in 1856 in je prejel naziv častnega meščana. Prva javna spo- the town. The first two public monuments erected in Ljublja- menika v Ljubljani sta bila posvečena »očetu Radeckemu«, na were dedicated to “Father Radetzky,” who was considered ki je med Slovenci veljal za »pravega narodnega heroja«. a “real national hero” by the Slovenians. However, when Ko pa je bila leta 1918 ustanovljena nova južnoslovanska Yugoslavia was established as a South Slavic state in 1918, država, spomenika, posvečena zmagovitemu avstrijskemu the two monuments dedicated to this victorious Austrian junaku, nista več ustrezala spremenjeni identiteti Slovencev. hero were no longer consistent with Slovenians’ changed self- V Ljubljani ni bilo več prostora za tega junaškega maršala, -identification. There was no room left in Ljubljana for this ki se je nekdaj bojeval z italijanskimi uporniki. heroic marshal, who once fought the Italian rebels. Ključne besede: avstrijski patriotizem, deavstrizacija, feld- Keywords: Austrian patriotism, de-Austrianization, Fi- maršal Radecki, politični simboli, javni spomeniki, »Ra- eld Marshal Radetzky, political symbols, public monu- deckijevo mesto«, spomenikomanija ments, “Radetzky’s city,” statuemania In the second half of the nineteenth century, the public monument joined the museum and theatre in the role of a representative object. It was Paris monuments that first represented republican meritocracy, as opposed to those based on aristocratic leanings. -

History of Urology at the Sestre Milosrdnice University Hospital Center

Acta Clin Croat (Suppl. 1) 2018; 57:9-20 Original Scientifi c Paper doi: 10.20471/acc.2018.57.s1.01 HISTORY OF UROLOGY AT THE SESTRE MILOSRDNICE UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL CENTER Boris Ružić1,2, Josip Katušić1, Borislav Spajić1,2, Ante Reljić1, Alek Popović1, Goran Štimac1, Igor Tomašković1,3, Šoip Šoipi1, Danijel Justinić1, Igor Grubišić1, Miroslav Tomić1, Matej Knežević1, Ivan Svaguša1, Ivan Pezelj1, Sven Nikles1, Matea Pirša1 and Borna Vrhovec1 1Department of Urology, Sestre milosrdnice University Hospital Center, Zagreb, Croatia; 2School of Medicine, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia; 3Faculty of Medicine, J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek, Osijek, Croatia SUMMARY – Th e history of Croatian urology clearly shows its affi liation to the medical and civilizational circle of the Western world. Th e Department of Urology at the Sestre milosrdnice Uni- versity Hospital Center is the oldest urology institution in the Republic of Croatia. Th e Department was established in 1894, when the new Sestre milosrdnice Hospital was open in Vinogradska cesta in Zagreb. It was then that doctor Dragutin Mašek founded the so-called III Department, which, in addition to treating urology patients, also treated patients with conditions of the ear, nose and throat, eye diseases and dermatologic conditions. Dragutin Mašek had already realized that medicine would soon be divided into fi elds and had assigned younger doctors joining the III Department to specifi c fi elds. As a result, urology was given to Aleksandar Blašković, who founded the fi rst independent de- partment of urology in Croatia in 1926. In 1927, he was appointed Professor of urology at the Zagreb School of Medicine, where he established the fi rst department of urology and was giving lectures and practicals. -

Los Nacionalismos Catalán Y Croata: Análisis Comparativo De Los Procesos De Creación De La Nación

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials dʼinvestigació i docència en els termes establerts a lʼart. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix lʼautorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No sʼautoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes dʼexplotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des dʼun lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc sʼautoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

Oligarchs, King and Local Society: Medieval Slavonia

Antun Nekić OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University CEU eTD Collection Budapest May2015 OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 by Antun Nekić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest Month YYYY OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 by Antun Nekić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. CEU eTD Collection ____________________________________________ External Reader Budapest Month YYYY OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 by Antun Nekić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Supervisor CEU eTD Collection Budapest Month YYYY I, the undersigned, Antun Nekić, candidate for the MA degree in Medieval Studies, declare herewith that the present thesis is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person’s or institution’s copyright. -

37. Zagreb Salon

37. ZAGREB SALON Međunarodna izložba fotografija International Exhibition of Photography Zagreb, 2016. 37. Zagreb salon Fotoklub Zagreb Ilica 29/III, 10000 Zagreb; tel: 01/4833359 [email protected]; www.fotoklubzagreb.hr; www.facebook.com/fotoklubzagreb Organizacija izložbe / Organization of the Exhibition: Fotoklub Zagreb Predsjednik Salona / Exhibition Chairman: Hrvoje Mahović Tajnica salona / Salon Secretary: Vera Jurić Organizacijski odbor / Organising Committee: Vera Jurić, Biljana Knebl, Božidar Kasal, Hrvoje Mahović, Zvonko Radičanin Nakladnik / Publisher: Fotoklub Zagreb Urednik / Editor: Hrvoje Mahović Lektura / Proofreading: Vesna Zednik Grafički dizajn / Graphic Design: Biljana Knebl Tisak / Print: Denona Naklada / Copies: 500 ISBN 978-953-7749-06-4 CIP zapis je dostupan u računalnome katalogu Nacionalne i sveučilišne knjižnice u Zagrebu pod brojem 000950148 CIP Catalogue record for this book is available from the National and University Library in Zagreb No. 000950148 2 2016/141 2016/01 2016/121 37. ZAGREB SALON Međunarodna izložba fotografija International Exhibition of Photography Pokrovitelji / Patronage Predsjednica Republike Hrvatske / President of the Republic of Croatia Ministarstvo kulture / Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Croatia Gradska skupština Grada Zagreba / City Council of Zagreb Gradonačelnik Grada Zagreba / Mayor of the city of Zagreb Grad Zagreb - Gradski ured za obrazovanje, kulturu i sport / City of Zagreb Office of Education, Culture and Sport 3 RIJEČ PREDSJEDNIKA SALONA Kao dugogodišnji član Fotokluba Zagreb, a od 2015. i njegov predsjednik, s velikim sam zadovoljstvom sudjelovao u svim fazama organizacije i realizacije 37. Zagreb salona. S obzirom na to da Zagreb salon ima stoljetnu tradiciju i da je jedan od najstarijih fotografskih salona u svijetu, njegova je organizacija jedna od najvažnijih klupskih aktivnosti. -

Framing Croatia's Politics of Memory and Identity

Workshop: War and Identity in the Balkans and the Middle East WORKING PAPER WORKSHOP: War and Identity in the Balkans and the Middle East WORKING PAPER Author: Taylor A. McConnell, School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh Title: “KRVatska”, “Branitelji”, “Žrtve”: (Re-)framing Croatia’s politics of memory and identity Date: 3 April 2018 Workshop: War and Identity in the Balkans and the Middle East WORKING PAPER “KRVatska”, “Branitelji”, “Žrtve”: (Re-)framing Croatia’s politics of memory and identity Taylor McConnell, School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh Web: taylormcconnell.com | Twitter: @TMcConnell_SSPS | E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper explores the development of Croatian memory politics and the construction of a new Croatian identity in the aftermath of the 1990s war for independence. Using the public “face” of memory – monuments, museums and commemorations – I contend that Croatia’s narrative of self and self- sacrifice (hence “KRVatska” – a portmanteau of “blood/krv” and “Croatia/Hrvatska”) is divided between praising “defenders”/“branitelji”, selectively remembering its victims/“žrtve”, and silencing the Serb minority. While this divide is partially dependent on geography and the various ways the Croatian War for Independence came to an end in Dalmatia and Slavonia, the “defender” narrative remains preeminent. As well, I discuss the division of Croatian civil society, particularly between veterans’ associations and regional minority bodies, which continues to disrupt amicable relations among the Yugoslav successor states and places Croatia in a generally undesired but unshakable space between “Europe” and the Balkans. 1 Workshop: War and Identity in the Balkans and the Middle East WORKING PAPER Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................... -

Hellozagreb5.Pdf

v ro e H s B o Šilobodov a u r a b a v h Put o h a r r t n e e o i k ć k v T T c e c a i a i c k Kozarčeve k Dvor. v v W W a a a Srebrnjak e l Stube l St. ć č Krležin Gvozd č i i s ć Gajdekova e k Vinogradska Ilirski e Vinkovićeva a v Č M j trg M l a a a Zamen. v č o e Kozarčeva ć k G stube o Zelengaj NovaVes m Vončinina v Zajčeva Weberova a Dubravkin Put r ić M e V v Mikloušić. Degen. Iv i B a Hercegovačka e k Istarska Zv k u ab on ov st. l on ar . ić iće Višnjica . e va v Šalata a Kuhačeva Franje Dursta Vladimira Nazora Kožarska Opatička Petrova ulica Novakova Demetrova Voćarska Višnjičke Ribnjak Voćarsko Domjanićeva stube naselje Voćarska Kaptol M. Slavenske Lobmay. Ivana Kukuljevića Zamenhoova Mletač. Radićeva T The closest and most charming Radnički Dol Posil. stube k v Kosirnikova a escape from Zagreb’s cityŠrapčeva noise e Jadranska stube Tuškanac l ć Tuškanac Opatovina č i i is Samobor - most joyful during v ć e e Bučarova Jurkovićeva J. Galjufa j j Markov v the famous Samobor Carnival i i BUS r r trg a Ivana Gorana Kovačića Visoka d d andJ. Gotovca widely known for the cream Bosanska Kamenita n n Buntićeva Matoševa A A Park cake called kremšnita. Maybe Jezuitski P Pantovčak Ribnjak Kamaufova you will have to wait in line to a trg v Streljačka Petrova ulica get it - many people arrive on l Vončinina i Jorgov. -

Croatia Itinerary: Zagreb, Split and Dubovnik/ Mostar (May 2018)

www.chewingawaycities.com Croatia itinerary: Zagreb, Split and Dubovnik/ Mostar (May 2018) Monday, May 21 LJUBLJANA > ZAGREB Address Remarks 8.45am - 9.45am Wake up and get ready 9.45pm - 10am Walk to bus station 8.25am - 10.43am (train) OR Ljubljana > Zagreb **Make sure it is a direct bus 10.25am - 12.45pm (Flixbus) OR 2.45pm - 5.10pm (train) - Via bus (2hr 20min), approx €11, boarding 15min before departure - A tip for anyone taking Flixbus at Ljubljana bus terminal - it was quite far from the train station and the sign is not clear, so be there early and check every bus plate. Bus ticket: www.ap-ljubljana.si Train ticket: http://www.slo-zeleznice.si 12.45pm - 1.30pm Zagreb bus station > Swanky Mint Hostel **CHECK ABOUT BUSES TO PLITVICE LAKE (bought) AND SPLIT (haven't buy) Tourist Information Centre located on the first floor Opening hours: Mon - Fri: 9am - 9pm Sat, Sun, PH: 10am - 5pm - Take tram number 6 from outside the station towards Crnomerec - Alight at Frankopanska (one stop after the main square/ 6th stop from the bus station) - Journey time: approx 15min - Tram tickets can be purchased at the little kiosks at each stop, or from the driver - Price: 10 Kuna (€1.30) and it's valid for 90min 1.30pm - 2pm Swanky Mint Hostel 50 Ilica, Zagreb, 10000, HR Booking ref: 145670675190 (via hotels.com) Total: sgd$160.26 (paid in full) Check in: 2pm Check out: 11am 2pm - 2.15pm Swanky Mint Hostel > Jelacic Square (10min walk) Ban Jelacic Square (Zagreb's main square) Here are a few highlights of Zagreb’s Upper Town (location of historic -

Vladimir-Peter-Goss-The-Beginnings

Vladimir Peter Goss THE BEGINNINGS OF CROATIAN ART Published by Ibis grafika d.o.o. IV. Ravnice 25 Zagreb, Croatia Editor Krešimir Krnic This electronic edition is published in October 2020. This is PDF rendering of epub edition of the same book. ISBN 978-953-7997-97-7 VLADIMIR PETER GOSS THE BEGINNINGS OF CROATIAN ART Zagreb 2020 Contents Author’s Preface ........................................................................................V What is “Croatia”? Space, spirit, nature, culture ....................................1 Rome in Illyricum – the first historical “Pre-Croatian” landscape ...11 Creativity in Croatian Space ..................................................................35 Branimir’s Croatia ...................................................................................75 Zvonimir’s Croatia .................................................................................137 Interlude of the 12th c. and the Croatia of Herceg Koloman ............165 Et in Arcadia Ego ...................................................................................231 The catastrophe of Turkish conquest ..................................................263 Croatia Rediviva ....................................................................................269 Forest City ..............................................................................................277 Literature ................................................................................................303 List of Illustrations ................................................................................324 -

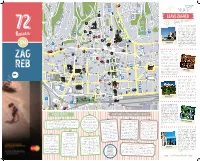

Zagreb Winter 2016/2017

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels Zagreb Winter 2016/2017 Trešnjevka Where wild cherries once grew Go Gourmet A Croatian feast Shopping Cheat Sheet Find your unique item N°86 - complimentary copy zagreb.inyourpocket.com Festive December Contents in Ljubljana ESSENTIAL CITY G UIDES Foreword 4 Sightseeing 46 A word of welcome Snap, camera, action Arrival & Getting Around 6 Zagreb Pulse 53 We unravel the A to Z of travel City people, city trends Zagreb Basics 12 Shopping 55 All the things you need to know about Zagreb Ready for a shopping spree Trešnjevka 13 Hotels 61 A city district with buzz The true meaning of “Do not disturb” Culture & Events 16 List of Small Features Let’s fill up that social calendar of yours Advent in Zagreb 24 Foodie’s Guide 34 Go Gourmet 26 Festive Lights Switch-on Event City Centre Shopping 59 Ćevap or tofu!? Both! 25. Nov. at 17:15 / Prešernov trg Winter’s Hot Shopping List 60 Restaurants 35 Maps & Index Festive Fair Breakfast, lunch or dinner? You pick... from 25. Nov. / Breg, Cankarjevo nabrežje, Prešernov in Kongresni trg Street Register 63 Coffee & Cakes 41 Transport Map 63 What a pleasure City Centre Map 64-65 St. Nicholas Procession City Map 66 5. Dec. at 17:00 / Krekov trg, Mestni trg, Prešernov trg Nightlife 43 Bop ‘till you drop Street Theatre 16. - 20. Dec. at 19:00 / Park Zvezda Traditional Christmas Concert 24. Dec. at 17:00 / in front of the Town Hall Grandpa Frost Proccesions 26. - 30. Dec. at 17:00 / Old Town New Year’s Eve Celebrations for Children 31. -

Peristil Prijelom52.Indd

Vladimir P. Goss, Tea Gudek: Some Very Old Sanctuaries... Peristil 52/2009 (7-26) Vladimir Peter Goss and Tea Gudek University of Rijeka, School of Arts and Science Some Very Old Sanctua- ries and the Emergence of 13. 10. 2009 Izvorni znanstveni rad / Original scientifi c paper Zagreb’s Cultural Landscape Key Words: Croatia, Zagreb, Prigorje, Medvednica, Cultural Landscape, the Slavs, sanctuaries Ključne riječi: Hrvatska, Zagreb, Prigorje, Medvednica, Kulturni pejsaž, Slaveni, svetišta The objective of this paper is to provide initial evidence of the pre-Christian, in particular early Slavic stratum of the cultural landscape in the Zagreb Prigorje (Cismontana) area. Following upon the research of Croatian linguists (R. Katičić) and cultural anthropologists (V. Belaj) the authors propose several sites, and structured associations thereof, which, in their opinion, played an important role as the foundations to the cultural landscape of Zagreb and the Zagreb Prigorje area, as we can at least partly reconstruct it today. These sites, located along the line St. Jakob-Medvedgrad-St.Marko, within the Remete »hoof,« along the line the Rog-the Stari Kip-Gradec (Zagreb), and those linked to St. Barbara are just initial examples of what might be achieved by a systematic continuous research. The paper also discusses methodology involved in studying cultural landscape, its signifi cance for the history of the visual arts, and the importance for contemporary interventions in our environment. Th e Croatian writer Antun Gustav Matoš (1873-1914) ssif, the -

The Ban's Mana

Cultural Studies ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcus20 The Ban’s mana: post-imperial affect and public memory in Zagreb Jeremy F. Walton To cite this article: Jeremy F. Walton (2020): The Ban’s mana: post-imperial affect and public memory in Zagreb, Cultural Studies, DOI: 10.1080/09502386.2020.1780285 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2020.1780285 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 16 Jun 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 134 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcus20 CULTURAL STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2020.1780285 The Ban’s mana: post-imperial affect and public memory in Zagreb Jeremy F. Walton Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity, Göttingen, Germany ABSTRACT How might scholars of public memory approach the protean relationship among imperial legacies, nationalized collective memories and urban space from an ‘off-center’ perspective? In this essay, I pursue this question in relation to a monument whose political biography traverses, and troubles, the distinction between imperial and national times, sentiments, and polities. The statue in question is that of Ban Josip Jelačić, a nineteenth Century figure who was both a loyal servant of the Habsburg Empire and a personification of nascent Croatian and South Slavic national aspirations. Jelačić’s monument was erected in Zagreb’s central square in 1866, only seven years following his death; in the heady political context of the Dual Monarchy, his apotheosis as a figure of regional rebellion caused consternation on the part of the Hungarian authorities.