The Adaptation of Junji Itō's Uzumaki in the Eyes Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

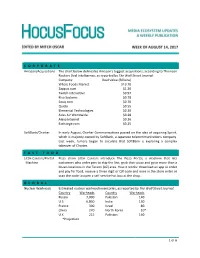

1 of 6 C O R P O R a T E Amazon/Acquisitions the Chart

CORPORATE Amazon/Acquisitions The chart below delineates Amazon’s biggest acquisitions, according to Thomson Reuters Deal Intelligence, as reported by The Wall Street Journal: Company Deal Value (Billions) Whole Foods MarKet $13.70 Zappos.com $1.20 Twitch Interactive $0.97 Kiva Systems $0.78 Souq.com $0.70 Quidsi $0.55 Elemental Technologies $0.30 Atlas Air Worldwide $0.28 Alexa Internet $0.26 Exchange.com $0.25 SoftBanK/Charter In early August, Charter Communications passed on the idea of acquiring Sprint, which is majority owned by SoftBanK, a Japanese telecommunications company. Last week, rumors began to circulate that SoftBank is exploring a complex taKeover of Charter. FAST FOOD Little Caesars/Portal Pizza chain Little Caesars introduce The Pizza Portal, a machine that lets Machine customers who order pies to skip the line, grab their pizza and go in more than a dozen locations in the Tucson (AZ) area. How it worKs: download an app to order and pay for food, receive a three digit or QR code and once in the store enter or scan the code to open a self-service hot box at the shop. GLOBAL Nuclear Warheads Estimated nuclear warhead inventories, as reported by The Wall Street Journal: Country Warheads Country Warheads Russia 7,000 Pakistan 140 U.S. 6,800 India 130 France 300 Israel 80 China 270 North Korea 10* U.K. 215 Pakistan 140 *Projection 1 of 6 MOVIES TicKet Sales According to Nielsen, North American box office ticKet sales are down 2.9% even with ticKet prices higher than the prior year – maKing up for some of the diminished theater attendance. -

The Internet and Drug Markets

INSIGHTS EN ISSN THE INTERNET AND DRUG MARKETS 2314-9264 The internet and drug markets 21 The internet and drug markets EMCDDA project group Jane Mounteney, Alessandra Bo and Alberto Oteo 21 Legal notice This publication of the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) is protected by copyright. The EMCDDA accepts no responsibility or liability for any consequences arising from the use of the data contained in this document. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the official opinions of the EMCDDA’s partners, any EU Member State or any agency or institution of the European Union. Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2016 ISBN: 978-92-9168-841-8 doi:10.2810/324608 © European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2016 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. This publication should be referenced as: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2016), The internet and drug markets, EMCDDA Insights 21, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. References to chapters in this publication should include, where relevant, references to the authors of each chapter, together with a reference to the wider publication. For example: Mounteney, J., Oteo, A. and Griffiths, P. -

Timeline 1994 July Company Incorporated 1995 July Amazon

Timeline 1994 July Company Incorporated 1995 July Amazon.com Sells First Book, “Fluid Concepts & Creative Analogies: Computer Models of the Fundamental Mechanisms of Thought” 1996 July Launches Amazon.com Associates Program 1997 May Announces IPO, Begins Trading on NASDAQ Under “AMZN” September Introduces 1-ClickTM Shopping November Opens Fulfillment Center in New Castle, Delaware 1998 February Launches Amazon.com Advantage Program April Acquires Internet Movie Database June Opens Music Store October Launches First International Sites, Amazon.co.uk (UK) and Amazon.de (Germany) November Opens DVD/Video Store 1999 January Opens Fulfillment Center in Fernley, Nevada March Launches Amazon.com Auctions April Opens Fulfillment Center in Coffeyville, Kansas May Opens Fulfillment Centers in Campbellsville and Lexington, Kentucky June Acquires Alexa Internet July Opens Consumer Electronics, and Toys & Games Stores September Launches zShops October Opens Customer Service Center in Tacoma, Washington Acquires Tool Crib of the North’s Online and Catalog Sales Division November Opens Home Improvement, Software, Video Games and Gift Ideas Stores December Jeff Bezos Named TIME Magazine “Person Of The Year” 2000 January Opens Customer Service Center in Huntington, West Virginia May Opens Kitchen Store August Announces Toys “R” Us Alliance Launches Amazon.fr (France) October Opens Camera & Photo Store November Launches Amazon.co.jp (Japan) Launches Marketplace Introduces First Free Super Saver Shipping Offer (Orders Over $100) 2001 April Announces Borders Group Alliance August Introduces In-Store Pick Up September Announces Target Stores Alliance October Introduces Look Inside The BookTM 2002 June Launches Amazon.ca (Canada) July Launches Amazon Web Services August Lowers Free Super Saver Shipping Threshold to $25 September Opens Office Products Store November Opens Apparel & Accessories Store 2003 April Announces National Basketball Association Alliance June Launches Amazon Services, Inc. -

Title Call # Category

Title Call # Category 2LDK 42429 Thriller 30 seconds of sisterhood 42159 Documentary A 42455 Documentary A2 42620 Documentary Ai to kibo no machi = Town of love & hope 41124 Documentary Akage = Red lion 42424 Action Akahige = Red beard 34501 Drama Akai hashi no shita no nerui mizu = Warm water under bridge 36299 Comedy Akai tenshi = Red angel 45323 Drama Akarui mirai = Bright future 39767 Drama Akibiyori = Late autumn 47240 Akira 31919 Action Ako-Jo danzetsu = Swords of vengeance 42426 Adventure Akumu tantei = Nightmare detective 48023 Alive 46580 Action All about Lily Chou-Chou 39770 Always zoku san-chôme no yûhi 47161 Drama Anazahevun = Another heaven 37895 Crime Ankokugai no bijo = Underworld beauty 37011 Crime Antonio Gaudí 48050 Aragami = Raging god of battle 46563 Fantasy Arakimentari 42885 Documentary Astro boy (6 separate discs) 46711 Fantasy Atarashii kamisama 41105 Comedy Avatar, the last airbender = Jiang shi shen tong 45457 Adventure Bakuretsu toshi = Burst city 42646 Sci-fi Bakushū = Early summer 38189 Drama Bakuto gaijin butai = Sympathy for the underdog 39728 Crime Banshun = Late spring 43631 Drama Barefoot Gen = Hadashi no Gen 31326, 42410 Drama Batoru rowaiaru = Battle royale 39654, 43107 Action Battle of Okinawa 47785 War Bijitâ Q = Visitor Q 35443 Comedy Biruma no tategoto = Burmese harp 44665 War Blind beast 45334 Blind swordsman 44914 Documentary Blind woman's curse = Kaidan nobori ryu 46186 Blood : Last vampire 33560 Blood, Last vampire 33560 Animation Blue seed = Aokushimitama blue seed 41681-41684 Fantasy Blue submarine -

Horror of Philosophy

978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page i In The Dust of This Planet [Horror of Philosophy, vol 1] 978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page ii 978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page iii In The Dust of This Planet [Horror of Philosophy, vol 1] Eugene Thacker Winchester, UK Washington, USA 978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page iv First published by Zero Books, 2011 Zero Books is an imprint of John Hunt Publishing Ltd., Laurel House, Station Approach, Alresford, Hants, SO24 9JH, UK [email protected] www.o-books.com For distributor details and how to order please visit the ‘Ordering’ section on our website. Text copyright: Eugene Thacker 2010 ISBN: 978 1 84694 676 9 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publishers. The rights of Eugene Thacker as author have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Design: Stuart Davies Printed in the UK by CPI Antony Rowe Printed in the USA by Offset Paperback Mfrs, Inc We operate a distinctive and ethical publishing philosophy in all areas of our business, from our global network of authors to production and worldwide distribution. -

Aug CUSTOMER ORDER FORM

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18 aug 2013 aug COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Aug13 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 7/3/2013 3:05:51 PM Available only DEADPOOL: “TACO ENTHUSIAST” from your local BLUE T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! THE WALKING DEAD: STREET FIGHTER: DOCTOR WHO: “THE DIXON BROS.” “THE STREETS” “DON’T BLINK” GLOW ZIP HOODIE RED T-SHIRT IN THE DARK T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now 8 Aug 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 7/3/2013 10:34:19 AM PrETTY DEADLY #1 ImAgE COmICS THE SHAOLIN COWBOY #1 DArk HOrSE COmICS THE SANDmAN: OVErTUrE #1 DC COmICS / VErTIgO VELVET #1 ELFQUEST SPECIAL: ImAgE COmICS THE FINAL QUEST DArk HOrSE COmICS SAmUrAI JACk #1 IDW PUBLISHINg SUPErmAN/WONDEr mArVEL kNIgHTS: WOmAN #1 SPIDEr-mAN #1 DC COmICS mArVEL COmICS Aug13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 7/3/2013 9:04:01 AM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Fox #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Uber Volume 1 Enhanced HC l AVATAR PRESS Imagine Agents #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS The Shadow Now #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Cryptozoic Man #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Peanuts Every Sunday 1952-1955 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Battling Boy GN/HC l :01 FIRST SECOND Letter 44 #1 l ONI PRESS 1 1 Ben 10 Omniverse Volume 1: Ghost Ship GN l PERFECT SQUARE X-O Manowar Deluxe HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Miss Peregrine’s Home For Peculiar Children HC l YEN PRESS BOOKS The Superman Files HC l COMICS Doctor Who 50th Anniversary Anthology l DOCTOR WHO Doctor Who: The Vault: Treasures from the First 50 Years HC l DOCTOR WHO Dc Comics Guide To Creating Comics Sc l HOW-TO Star Trek: Mr. -

Fusion of Technology Management and Financing Management - Amazon's Transformative Endeavor by Orchestrating Techno-Financing Systems

Journal Pre-proof Fusion of technology management and financing management - Amazon's transformative endeavor by orchestrating techno-financing systems Yuji Tou, Chihiro Watanabe, Pekka Neittaanmäki PII: S0160-791X(19)30374-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.101219 Reference: TIS 101219 To appear in: Technology in Society Received Date: 7 August 2019 Revised Date: 11 October 2019 Accepted Date: 26 November 2019 Please cite this article as: Tou Y, Watanabe C, Neittaanmäki P, Fusion of technology management and financing management - Amazon's transformative endeavor by orchestrating techno-financing systems, Technology in Society (2020), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.101219. This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. © 2019 Published by Elsevier Ltd. TIS_2019_345_title_page_Revised Fusion of Technology Management and Financing Management - Amazon’s Transformative Endeavor by Orchestrating Techno-financing Systems Yuji Tou 1, Chihiro Watanabe 2 ,3 , Pekka Neittaanmäki 2 1 Dept. of Ind. Engineering & Magm., Tokyo Institute of Technology, Tokyo, Japan 2 Faculty of Information Technology, University of Jyväskylä, Finland 3 International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Austria Abstract Amazon became the world R&D leader in 2017 by rapidly increasing R&D investment. -

Impact Analysis of Wireless and Mobile Technology on Business Management Strategies Rashed Azim East India Services Limited, London

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Information and Knowledge Management www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-5758 (Paper) ISSN 2224-896X (Online) Vol.3, No.2, 2013 Impact analysis of wireless and mobile technology on business management strategies Rashed Azim East India Services Limited, London Azizul Hassan Tourism Consultants Network, the Tourism Society Telephone Number: 0044 07853024625; Email: [email protected] Abstract: This research examines whether congruence exists between wireless and mobile technology with impact analysis on a firm’s business management development and future strategies. The research adopted the Motorola Inc. as a case and the qualitative approach as the research method. It emerged from analysis that consumers, business management strategies and future strategic directions are embedded in wireless and mobile technology. Despite having high tech wireless and mobile technology, it is not always been possible to appear as the market leader within industry, where future consumer behaviour and business management strategies will differ from the one those exist today. This study proposes a new framework for diversifying intellectual capacity to develop consultancy based growth opportunity at Motorola. This also suggests intense mobile and wireless technological impacts on relationships with customers, enterprise agility and business management strategies in the internet based market structure. Keywords: wireless and mobile technology, process automation, cloud infrastructure, convergence, business management strategy Introduction: Demand for investigation of wireless and mobile technological influences on corporate and business management strategies with impacts on consumers are increasing. -

2. Case Study: Anime Music Videos

2. CASE STUDY: ANIME MUSIC VIDEOS Dana Milstein When on 1 August 1981 at 12:01 a.m. the Buggles’ ‘Video Killed the Radio Star’ aired as MTV’s first music video, its lyrics parodied the very media pre- senting it: ‘We can’t rewind, we’ve gone too far, . put the blame on VTR.’ Influenced by J. G. Ballard’s 1960 short story ‘The Sound Sweep’, Trevor Horn’s song voiced anxiety over the dystopian, artificial world developing as a result of modern technology. Ballard’s story described a world in which natu- rally audible sound, particularly song, is considered to be noise pollution; a sound sweep removes this acoustic noise on a daily basis while radios broad- cast a silent, rescored version of music using a richer, ultrasonic orchestra that subconsciously produces positive feelings in its listeners. Ballard was particu- larly criticising technology’s attempt to manipulate the human voice, by con- tending that the voice as a natural musical instrument can only be generated by ‘non-mechanical means which the neruophonic engineer could never hope, or bother, to duplicate’ (Ballard 2006: 150). Similarly, Horn professed anxiety over a world in which VTRs (video tape recorders) replace real-time radio music with simulacra of those performances. VTRs allowed networks to replay shows, to cater to different time zones, and to rerecord over material. Indeed, the first VTR broadcast occurred on 25 October 1956, when a recording of guest singer Dorothy Collins made the previous night was broadcast ‘live’ on the Jonathan Winters Show. The business of keeping audiences hooked 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, promoted the concept of quantity over quality: yes- terday’s information was irrelevant and could be permanently erased after serving its money-making purpose. -

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 FEB 2015 FEB COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/8/2015 3:45:07 PM Feb15 IFC Future Dudes Ad.indd 1 1/8/2015 9:57:57 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Shield #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Sonic/Mega Man: Worlds Collide: The Complete Epic TP l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Badlands #75 l AVATAR PRESS INC Extinction Parade Volume 2: War TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Lady Mechanika: The Tablet of Destinies #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS UFOlogy #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Lumberjanes Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Masks 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Jungle Girl Season 3 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Uncanny Season 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Supermutant Magic Academy GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Rick & Morty #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Bloodshot Reborn #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC GYO 2-in-1 Deluxe Edition HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books l COMICS Taschen’s The Bronze Age Of DC Comics 1970-1984 HC l COMICS Neil Gaiman: Chu’s Day at the Beach HC l NEIL GAIMAN Darth Vader & Friends HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection Special #5: Klingon Bird-of-Prey l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #2 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man Magazine #3 l COMICS Doctor Who Special #40 l DOCTOR WHO 2 TRADING CARDS Topps 2015 Baseball Series 2 Trading Cards l TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL DC Heroes: Aquaman Navy T-Shirt l PREVIEWS EXCLUSIVE WEAR 2 DC Heroes: Harley Quinn “Cells” -

Evaluation of Nigeria Universities Websites Using Alexa Internet Tool: a Webometric Study

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 2020 Evaluation of Nigeria Universities Websites Using Alexa Internet Tool: A Webometric Study Samuel Oluranti Oladipupo Mr University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Oladipupo, Samuel Oluranti Mr, "Evaluation of Nigeria Universities Websites Using Alexa Internet Tool: A Webometric Study" (2020). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 4549. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/4549 Evaluation of Nigeria Universities Websites Using Alexa Internet Tool: A Webometric Study Samuel Oluranti, Oladipupo1 Africa Regional Centre for Information Science, University of Ibadan, Nigeria E-mail:[email protected] Abstract This paper seeks to evaluate the Nigeria Universities websites using the most well-known tool for evaluating websites “Alexa Internet” a subsidiary company of Amazon.com which provides commercial web traffic data. The present study has been done by using webometric methods. The top 20 Nigeria Universities websites were taken for assessment. Each University website was searched in Alexa databank and relevant data including links, pages viewed, speed, bounce percentage, time on site, search percentage, traffic rank, and percentage of Nigerian/foreign users were collected and these data were tabulated and analysed using Microsoft Excel worksheet. The results of this study reveal that Adekunle Ajasin University has the highest number of links and Ladoke Akintola University of Technology with the highest number of average pages viewed by users per day. Covenant University has the highest traffic rank in Nigeria while University of Lagos has the highest traffic rank globally. -

In the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas Tyler Division

CaseCase 6:06-cv-00452-LED 6:06-cv-00452-LED Document Document 22 27 Filed Filed 02/20/2007 02/26/07 Page Page 1 of 1 15of 15 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS TYLER DIVISION INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS ) MACHINES CORPORATION, ) ) Plaintiff, ) Civil Action No. 6:06-cv-452 ) JURY v. ) ) AMAZON.COM, INC., AMAZON ) SERVICES LLC F/K/A AMAZON ) SERVICES, INC. D/B/A AMAZON ) ENTERPRISE SOLUTIONS AND ) AMAZON SERVICES BUSINESS ) SOLUTIONS, AMAZON.COM INT’L ) SALES, INC. D/B/A AMAZON.CO.JP, ) AMAZON EUROPEAN UNION S.À.R.L. ) D/B/A AMAZON.DE, AMAZON.FR AND ) AMAZON.CO.UK, AMAZON SERVICES ) EUROPE S.À.R.L. D/B/A AMAZON.DE, ) AMAZON.FR AND AMAZON.CO.UK, ) AMAZON.COM.CA, INC., A9.COM, INC., ) ALEXA INTERNET D/B/A ALEXA ) INTERNET, INC. AND ALEXA ) INTERNET CORP., INTERNET MOVIE ) DATABASE, INC., CUSTOMFLIX LABS, ) INC., MOBIPOCKET.COM SA, ) AMAZON.COM LLC D/B/A ) ENDLESS.COM, BOP, LLC D/B/A ) SHOPBOP.COM, AMAZON WEB ) SERVICES, LLC, AND AMAZON ) SERVICES CANADA, INC., ) ) Defendants. ) FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiff International Business Machines Corporation (“IBM”), for its First Amended Complaint for Patent Infringement against Defendants Amazon.com, Inc., Amazon Services LLC f/k/a Amazon Services, Inc. d/b/a Amazon Enterprise Solutions and Amazon Services KING/KAPLAN FIRST AMENDED PATENT COMPLAINT DLI-6098701v2 CaseCase 6:06-cv-00452-LED 6:06-cv-00452-LED Document Document 22 27 Filed Filed 02/20/2007 02/26/07 Page Page 2 of 2 15of 15 Business Solutions, Amazon.com Int’l Sales, Inc.