Addis Ababa University School of Graduate Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOREWORD Statistical Data That Reflect the Socio-Economic And

FOREWORD Statistical data that reflect the socio-economic and demographic conditions of the residents of a country are useful for designing and preparation of development plans as well as for monitoring and evaluation of the impact of the implementation of the development plans. These statistical data include population size, age, sex, literacy and education, marital status, housing stocks and conditions …etc. In order to fill the gap for these socio-economic and demographic data need, Ethiopia has conducted its third Population and Housing Census in the months of May and November 2007. The 2007 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia was conducted under the auspices of the Population Census Commission that was established by a proclamation No. 449/1997. The Commission is chaired by the Deputy Prime Minister and the members of the commission were drawn from various relevant Ministries, Regional state representatives, House of Federation, National Electoral Board and the Central Statistical Agency, serving as the Office of the Census Commission (Secretariat). According to the proclamation, the processing, evaluation and analyses of the data collected in this census as well as its dissemination are the major responsibilities of this office. Thus, the Office of the Population Census Commission is pleased to present the census report entitled “The 2007 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia: Statistical Report for Addis Ababa City Administration” for the users. Subsequently, another report which deals with detailed analysis of the result of the 2007 Population and Housing Census data is in the process of being prepared and will also be prepared and printed soon. Before the conduct of a census enumeration, numbers of preparatory activities were also carried-out. -

Exporting Zionism

Exporting Zionism: Architectural Modernism in Israeli-African Technical Cooperation, 1958-1973 Ayala Levin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Ayala Levin All rights reserved ABSTRACT Exporting Zionism: Architectural Modernism in Israeli-African Technical Cooperation, 1958-1973 Ayala Levin This dissertation explores Israeli architectural and construction aid in the 1960s – “the African decade” – when the majority of sub-Saharan African states gained independence from colonial rule. In the Cold War competition over development, Israel distinguished its aid by alleging a postcolonial status, similar geography, and a shared history of racial oppression to alleviate fears of neocolonial infiltration. I critically examine how Israel presented itself as a model for rapid development more applicable to African states than the West, and how the architects negotiated their professional practice in relation to the Israeli Foreign Ministry agendas, the African commissioners' expectations, and the international disciplinary discourse on modern architecture. I argue that while architectural modernism was promoted in the West as the International Style, Israeli architects translated it to the African context by imbuing it with nation-building qualities such as national cohesion, labor mobilization, skill acquisition and population dispersal. Based on their labor-Zionism settler-colonial experience, -

Addis Ababa City Structure Plan

Addis Ababa City Structure Plan DRAFT FINAL SUMMARY REPORT (2017-2027) AACPPO Table of Content Part I Introduction 1-31 1.1 The Addis Ababa City Development Plan (2002-2012) in Retrospect 2 1.2 The National Urban System 1.2 .1 The State of Urbanization and Urban System 4 1.2 .2 The Proposed National Urban System 6 1.3 The New Planning Approach 1.3.1 The Planning Framework 10 1.3.2 The Planning Organization 11 1.3.3 The Legal framework 14 1.4 Governance and Finance 1.4.1 Governance 17 1.4.2 Urban Governance Options and Models 19 1.4.3 Proposal 22 1.4.4 Finance 24 Part II The Structure Plan 32-207 1. Land Use 1.1 Existing Land Use 33 1.2 The Concept 36 1.3 The Proposal 42 2. Centres 2.1 Existing Situation 50 2.2 Hierarchical Organization of Centres 55 2.3 Major Premises and Principles 57 2.4 Proposals 59 2.5 Local development Plans for centres 73 3. Transport and the Road Network 3.1 Existing Situation 79 3.2 New Paradigm for Streets and Mobility 87 3.3 Proposals 89 4. Social Services 4.1 Existing Situation 99 4.2 Major Principles 101 4.3 Proposals 102 i 5. Municipal Services 5.1 Existing Situation 105 5.2 Main Principles and Considerations 107 5.3 Proposals 107 6. Housing 6.1 Housing Demand 110 6.2 Guiding Principles, Goals and Strategies 111 6.3 Housing Typologies and Land Requirement 118 6.4 Housing Finance 120 6.5 Microeconomic Implications 121 6.6 Institutional Arrangement and Regulatory Intervention 122 6.7 Phasing 122 7. -

IDENTIFYING MAJOR URBAN ROAD TRAFFIC ACCIDENT BLACK-SPOTS (Rtabss): a SUB-CITY BASED ANALYSIS of EVIDENCES from the CITY of ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA

Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa (Volume 15, No.2, 2013) ISSN: 1520-5509 Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania IDENTIFYING MAJOR URBAN ROAD TRAFFIC ACCIDENT BLACK-SPOTS (RTABSs): A SUB-CITY BASED ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCES FROM THE CITY OF ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA Guyu Ferede Daie Addis Ababa University (AAU), Ethiopia ABSTRACT Despite its adverse socio-economic impact, a study on identification of road traffic accident black-spots (RTABSs) in Addis Ababa is either negligible or only a general attempt made for the city as a whole (National Road Safety Coordination Office, [NRSCO], 2005) without considering the specific experiences of each sub-city. The main aim of this study was, therefore, to identify the major accident black spots in each sub-city of Addis Ababa separately. For this purpose, secondary data obtained from Addis Ababa traffic police office was employed. The findings of the study revealed that there were 125 major accident black-spots in Addis Ababa as a whole. The distribution by sub-city shows10, 11, 24, 10, 21, 10, 20, 6, 4 and 9 RTABSs in Kirkos, Bole, Arada , Yeka, Lideta, Nifas-Silk/Lafto, Addis-Ketema, Akaki, Kolfe and Gullele sub-cities respectively. This has implication on the need for sustainable transport development planning. The RTABSs identified in each sub-city need to be focused while planning. Therefore, concerned bodies should encourage further investigation of specific causes for designing and implementing appropriate road safety control strategies in order to significantly reduce the incidence of road crashes in the city. This can be done by planning sustainable ways of designing transport system such as road networks that should accommodate the ever increasing number of vehicles followed by frequent inspection of vehicles themselves. -

Urban Quality of Life and Its Spatial Distribution in Addis Ababa: Kirkos Sub-City

Urban Quality of Life and Its Spatial Distribution in Addis Ababa: Kirkos sub-city Elsa Sereke Tesfazghi March, 2009 Urban Quality of Life and Its Spatial Distribution In Addis Ababa: Kirkos sub-city By Elsa Sereke Tesfazghi Thesis submitted to the International Institute for Geo-information Science and Earth Observation in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geo-information Science and Earth Observation, Specialisation: (Urban Planning and Management) Thesis Assessment Board Prof.Dr.Ir. M.F.A.M. van Maarseveen (Chairman) Dr. Karin Pfeffer (External Examiner) Dr. J.A. Martinez (First Supervisor) Drs J.J. Verplanke (Second Supervisor) INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR GEO-INFORMATION SCIENCE AND EARTH OBSERVATION ENSCHEDE, THE NETHERLANDS Disclaimer This document describes work undertaken as part of a programme of study at the International Institute for Geo-information Science and Earth Observation. All views and opinions expressed therein remain the sole responsibility of the author, and do not necessarily represent those of the institute. Dedicated to my late mother Tekea Gebru and my late sister Zufan Sereke Abstract Urban quality of life (QoL) is becoming the subject of urban research mainly in western and Asian countries. Such attention is due to an increasing awareness of the contribution of QoL studies in identifying problem areas and in monitoring urban planning policies. However, most studies are carried out at city or country level that commonly average out details at small scales. The result is that the variability of QoL at small scales is not well known. In addition, the relationship between subjective and objective QoL is not well known. -

Modeling the Conflicts of Crossing Pedestrian with Vehicles in Turning Right at Signalized Intersections

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY ADDIS ABABA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES SCHOOL OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING MODELING THE CONFLICTS OF CROSSING PEDESTRIAN WITH VEHICLES IN TURNING RIGHT AT SIGNALIZED INTERSECTIONS By: Michael Asseged Belay A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science In Road and Transport Engineering Research Advisor: Bikila Teklu Wodajo (PhD) June, 2019 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY ADDIS ABABA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES SCHOOL OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING MODELING THE CONFLICTS OF CROSSING PEDESTRIAN WITH VEHICLES IN TURNING RIGHT AT SIGNALIZED INTERSECTIONS By: Michael Asseged Belay A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science In Road and Transport Engineering Approved by Board of Examiners: Advisor Signature Date Internal Examiner Signature Date External Examiner Signature Date Chair person Signature Date UNDERTAKING I certify that research work titled “Modeling the Conflicts of Crossing Pedestrian with Vehicles in Turning Right at Signalized Intersections” is my own work. The work has not been presented elsewhere for assessment. Where material has been used from other sources it has been properly acknowledged / referred. Signature: _______________ Undertaker‟s Full Name: Michael Asseged Belay Place of Undertaking: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Date: June, 2019 i ABSTRACT A great number of problems persist in Addis Ababa traffic networks for its huge population. The high level of conflict between pedestrians and motor vehicles at intersections is one of the most obvious. It is necessary to study the interaction mechanism of pedestrians and right-turn vehicles in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. -

City Profile Addis Ababa

SES Social Inclusion and Energy Managment for Informal Urban Settlements CITY PROFILE ADDIS ABABA Abnet Gezahegn Berhe, Dawit Benti Erena, Imam Mahmoud Hassen, Tsion Lemma Mamaru, Yonas Alemayehu Soressa CITY PROFILE ADDIS ABABA Abnet Gezahegn Berhe, Dawit Benti Erena, Imam Mahmoud Hassen, Tsion Lemma Mamaru, Yonas Alemayehu Soressa Funded by the Erasmus+ program of the European Union The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. The views expressed in this work and the accuracy of its findings is matters for the author and do not necessarily represent the views of or confer liability on the Centre of Urban Equity. © EiABC- Ethiopian Institute of Architecture Building Construction and City Development.. This work is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Contact: EiABC, P.O.Box 518, Addis Ababa www.eiabc.edu.et Suggested Reference: Erena D. et.al, (2017) City profile: Addis Ababa. Report prepared in the SES (Social Inclusion and Energy Management for Informal Urban Settlements) project, funded by the Erasmus+ Program of the European Union. http://moodle.donau-uni.ac.at/ses/ 2 CITY PROFILE ADDIS ABABA ABSTRACT Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia and the The reaction of the present government to these chal- diplomatic centre of Africa, embodies a 130 years lenges is expressed in its growth and transformation of development history that contributes to its cur- programme that embrace the urban development rent socio-spatial features. -

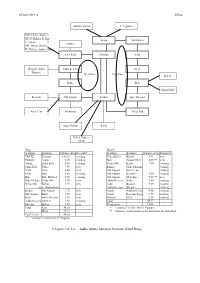

S.Figure 9.8-1-A Addis Ababa Junction Network (Dual Ring) S.Figure 9.8-1-A S.Ring

S.Figure 9.8-1-a D.Ring Addisu Gebeya F. Legation NW: Fitche, Kuyu NE: D.Birhan, D.Sina Arada Sidist Kilo S: Sebeta (MSC) SW: Ghion, Wolkite W: Holeta, Ambo, Guder AA TR-III Filwoha Yeka Shegole, Asko, Addis Ketema Gerji Burayu West Ring East Ring Kotebe Kolfe Bole Airport DLC Keranio Old Airport Kirkos Bole Michael Ayer Tena Mekanisa Nefas Silk Hana Mariam Kaliti D.Zeit, Dukem, Akaki Ring Branch A station B station Distance (km) Remarks* A station B station Distance (km) Remarks* TR/ITE Filwoha 1.6/2.0 existing Yeka (Bole) Kotebe5.84 new Filwoha Arada3.00 existing Bole Airport DLC4.00 ** new Arada Sidist Kilo5.20 existing Nefas Silk Kaliti7.40 existing Sidist Kilo Yeka7.90 new Kirkos Hana Mariam existing Yeka Gerji6.40 new Old Airport Ayer Tena existing Gerji Bole5.50 existing Old Airport Keranio5.50 existing Bole Bole Michael4.50 existing Old Airport Mekanisa5.00 ** new Bole Michael Nefas Silk3.70 new Addis Ketema Asko7.60 existing Nefas Silk Kirkos4.50 new Asko Burayu5.00 existing (route duplication) Addis Ketema Shegole existing Kirkos Old Airport3.72 new Arada Addisu Gebeya 4.80 existing Old Airport Kolfe7.20 new Arada Ferensay Lega 6.33 existing Kolfe Addis Ketema3.10 new Filwoha ECA2.80 existing Addis Ketema TR/ITE3.60 existing Total 54.27 Filwoha Kirkos3.50 new Total (new) 14.84 Total East44.20 * "existing" includes 8th D. Program West23.12 ** Distance is provisional as the location is not identified. Total (new) 40.02 * "existing" includes 8th D. Program S.Figure 9.8-1-a Addis Ababa Junction Network (Dual Ring) S.Figure 9.8-1-a S.Ring Addisu Gebeya F. -

Done at Addis Ababa

h^{\ Mm ADDIS NEGARI GAZETA OF THE CITY GOVERNMENT OF ADDIS ABABA nd 2 year No 21 ADDIS ABABA 2010 CONTENTS p^^ft ^nn h+'^ ^ft+^&c Nft^ci'^.T A Proclamation to Provide for the Amendment of the Addis Ababa City Government Executive and Municipality Services Organs Re-establishment Proclamation No 15/2009 Proclamation No 21/2010 ?tx^{\ ^n^ h+'^ hti-tfifLC P'^H;??? A Proclamation to Amend the Addis Ababa City Government Executive and Municipality Services Organs Re-establishment Proclamation No 15/2009 Whereas, it is found beneficial to reorganize Kebele Administrations within the Addis Ababa City Government into Wereda with the view to enable them render efficient, ^7A'7A-^ <^>flm•^ A'^^^^A m;!*"^. fair and effective services to residents; h^+? 'n .Prtn A'b^ PlfV9 P^^TJ-fl ^1•^ ^Oh') Whereas, it is found necessary to identify and divide +nA.;"^ n^AP•^ n'^h^A pvn<iah'> Kebeles that are geographically wide and densely p'>pulated so that the existing 99 Kebeles organized into 116 Weredas; +nA,;"^ nh^t\ hm f'^il' p'^J&fr'^ Pi^Tf-n Whereas, besides the fact that the Kebeles in Addis Ababa P'T.rtm •^ ^l^A•?A-^ nA,A-^ hA/V-Y consist population and render services compatible to that of \\ao\r^9° nAj& ft^'^oh'} nh-h'^ox h'^h'i^a)• Wereda in other Regional States it is believed that the ^^M^;^'E AfflT ^A^C ;JC naming Kebele be replaced by Wereda so that make it rt«7rtirnj>» ?,'>^?^A +nA, P'^AO)' fl.P'^ (D^^ compatible with the business process reengineering practice; n*^Aa)- ?i'>^+h flA;^^VI h-lrt V/J<^ /Jit.«J ?S"op5§ Addis Negari Gazeta P.O.Box 2445 Unit Price 4.85 7X- e h^ft "iPi p\^"\ *TC *7'>n•^ « 4''> e?i.u e 'j.j*". -

Urban Open Space Use in Addis Ababa: the Case of Meskel

URBAN OPEN SPACE USE IN ADDIS ABABA: THE CASE OF MESKEL SQUARE Mikyas Tesfaye Aragaw Användningen av de urbana friytorna i Addis Ababa: Exemplet Meskel Square Master Thesis in the program Urban Landscape Dynamics, 30 hp Självständigt arbete vid LTJ-fakulteten, SLU Faculty of Landscape Planning, Horticulture and Agricultural Sciences, Department of Landscape Architecture, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Alnarp, 2011 SLU, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Alnarp Faculty of Landscape Planning, Horticulture and Agricultural Sciences, Department of Landscape Architecture, Självständigt arbete vid LTJ-fakulteten, SLU Urban Open Space Use in Addis Ababa: The case of Meskel Square Användningen av de urbana friytorna i Addis Ababa: Exemplet Meskel Square Keywords: Addis Ababa, Urban Open Space, Meskel Square, User Trends Supervisor: Gunilla Lindholm, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Alnarp, Department of Landscape Architecture Examinor: Eva Gustavsson, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Alnarp, Department of Landscape Architecture Assistant Examinor: Pär Gustafsson, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Alnarp, Department of Landscape Architecture EX0377 Master Thesis in Landscape Planning, LTJ Fakulteten, SLU, 30 hp Degree Project in the Master Program Urban Landscape Dynamics Level: E Mikyas Tesfaye Aragaw 2011, Alnarp i Preface This master thesis is inspired by my experience in my two years stay in the Swedish cities, Stockholm, Malmö and Lund. When arriving in these cities, the first thing that fascinated me the most was the urban open spaces. These were public parks, cemetery parks, green ways and gray open spaces. The way they were designed, the way the people used them and the general image they give to the cities attracted my attention. -

Assessment of the Problems of On-Street Parking in the City of Addis Ababa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Academic Repository of Ethiopia ADDIS ABABA SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE AND CIVIL ENGINEERING, DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL ENGINEERING, GRADUATE STUDIES ROAD AND TRANSPORT ENGINEERING STREAM Assessment Of The Problems Of On-Street Parking In The City Of Addis Ababa. (A Case Study: on Megenagna Junction to Safety Intersection Street). BY MIRESA TEFERA ADVISOR ALEMAYEHU AMBO, PhD A thesis submitted to the College of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Graduate Studies of the Addis Ababa Science & Technology University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters of Science in Civil Engineering (Road and Transport Engineering Stream). January, 2017 Addis Ababa 1 ADDIS ABABA SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE AND CIVIL ENGINEERING, DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL ENGINEERING, GRADUATE STUDIES ROAD AND TRANSPORT ENGINEERING STREAM Assessment Of The Problems Of On-Street Parking In The City Of Addis Ababa. (A Case Study: Megenagna Junction To Safety Intersection Street). By Miresa Tefera Approved by The Board of Examiners: Dr. Alemayehu Ambo __________ Advisor Signature Date Dr. Fistum Tesfaye __________ Internal Examiner Signature Date Dr. Bikila Teklu __________ External Examiner Signature Date Dr. Brook Abate __________ Dean, College of Architecture Signature Date and Civil Engineering Mr. Addisu Bekele __________ Head of Civil Eng'g department Signature Date 2 Statement of Certification This is to certify that Miresa Tefera has carried out his research work on the topic entitled “Assessment Of The Problems Of On-Street Parking In The City Of Addis Ababa. A Case Of Megenagna Junction To Safety Intersection Street”. -

Commuter Exposure to Particulate Matters and Total Volatile Organic Compounds at Roadsides in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-018-2116-x ORIGINAL PAPER Commuter exposure to particulate matters and total volatile organic compounds at roadsides in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia A. Embiale1 · F. Zewge1 · B. S. Chandravanshi1 · E. Sahle‑Demessie2 Received: 17 May 2018 / Revised: 28 September 2018 / Accepted: 12 November 2018 © Islamic Azad University (IAU) 2018 Abstract People living in urban areas face diferent air-pollution-related health problems. Commuting is one of the high-exposure periods among various daily activities, especially in high-vehicle-congestion metropolitan areas. The aim of this work was to investigate the commuter exposure assessment to particulate matters with diferent aerodynamic diameter (< 1 µm to total suspended particles) and total volatile organic compounds using sensors called AROCET531S and AEROQUAL series 500, respectively. A total of 10 sub-cities at main roadsides of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, were selected, and the sampling period was during commuting time. The geometric mean of particulate matters with diferent aerodynamic diameters and total volatile organic compounds regardless of sampling time were ranged 6.79–496 and 220–439 µg m−3, respectively. The highest and the lowest concentrations for particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter 1, 2.5, and 4 µm pollutants were seen at Kolfe Keranio and Nefas Silk-Lafto sub-cities, respectively. And, highest and the lowest values for particulate matter with aerody- namic diameter 7 and 10 µm and total suspended particles were noticed at Addis Ketema and Gulelle sub-cities, respectively. Besides, the highest and the lowest values for total volatile organic compounds pollutants were noticed at Addis Ketema and Nefas Silk-Lafto sub-cities, respectively.