Aneurin Bevan and the Socialist Ideal Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Attlee Governments

Vic07 10/15/03 2:11 PM Page 159 Chapter 7 The Attlee governments The election of a majority Labour government in 1945 generated great excitement on the left. Hugh Dalton described how ‘That first sensa- tion, tingling and triumphant, was of a new society to be built. There was exhilaration among us, joy and hope, determination and confi- dence. We felt exalted, dedication, walking on air, walking with destiny.’1 Dalton followed this by aiding Herbert Morrison in an attempt to replace Attlee as leader of the PLP.2 This was foiled by the bulky protection of Bevin, outraged at their plotting and disloyalty. Bevin apparently hated Morrison, and thought of him as ‘a scheming little bastard’.3 Certainly he thought Morrison’s conduct in the past had been ‘devious and unreliable’.4 It was to be particularly irksome for Bevin that it was Morrison who eventually replaced him as Foreign Secretary in 1951. The Attlee government not only generated great excitement on the left at the time, but since has also attracted more attention from academics than any other period of Labour history. Foreign policy is a case in point. The foreign policy of the Attlee government is attractive to study because it spans so many politically and historically significant issues. To start with, this period was unique in that it was the first time that there was a majority Labour government in British political history, with a clear mandate and programme of reform. Whereas the two minority Labour governments of the inter-war period had had to rely on support from the Liberals to pass legislation, this time Labour had power as well as office. -

Crossing the Floor Roy Douglas a Failure of Leadership Liberal Defections 1918–29 Senator Jerry Grafstein Winston Churchill As a Liberal J

Journal of Issue 25 / Winter 1999–2000 / £5.00 Liberal DemocratHISTORY Crossing the Floor Roy Douglas A Failure of Leadership Liberal Defections 1918–29 Senator Jerry Grafstein Winston Churchill as a Liberal J. Graham Jones A Breach in the Family Megan and Gwilym Lloyd George Nick Cott The Case of the Liberal Nationals A re-evaluation Robert Maclennan MP Breaking the Mould? The SDP Liberal Democrat History Group Issue 25: Winter 1999–2000 Journal of Liberal Democrat History Political Defections Special issue: Political Defections The Journal of Liberal Democrat History is published quarterly by the Liberal Democrat History Group 3 Crossing the floor ISSN 1463-6557 Graham Lippiatt Liberal Democrat History Group Editorial The Liberal Democrat History Group promotes the discussion and research of 5 Out from under the umbrella historical topics, particularly those relating to the histories of the Liberal Democrats, Liberal Tony Little Party and the SDP. The Group organises The defection of the Liberal Unionists discussion meetings and publishes the Journal and other occasional publications. 15 Winston Churchill as a Liberal For more information, including details of publications, back issues of the Journal, tape Senator Jerry S. Grafstein records of meetings and archive and other Churchill’s career in the Liberal Party research sources, see our web site: www.dbrack.dircon.co.uk/ldhg. 18 A failure of leadership Hon President: Earl Russell. Chair: Graham Lippiatt. Roy Douglas Liberal defections 1918–29 Editorial/Correspondence Contributions to the Journal – letters, 24 Tory cuckoos in the Liberal nest? articles, and book reviews – are invited. The Journal is a refereed publication; all articles Nick Cott submitted will be reviewed. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

The Labour Party and the Idea of Citizenship, C. 193 1-1951

The Labour Party and the Idea of Citizenship, c. 193 1-1951 ABIGAIL LOUISA BEACH University College London Thesis presented for the degree of PhD University of London June 1996 I. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the development and articulation of ideas of citizenship by the Labour Party and its sympathizers in academia and the professions. Setting this analysis within the context of key policy debates the study explores how ideas of citizenship shaped critiques of the relationships between central government and local government, voluntary groups and the individual. Present historiographical orthodoxy has skewed our understanding of Labour's attitude to society and the state, overemphasising the collectivist nature and centralising intentions of the Labour party, while underplaying other important ideological trends within the party. In particular, historical analyses which stress the party's commitment from the 1930s to achieving the transition to socialism through a strategy of planning, (of industrial development, production, investment, and so on), have generally concluded that the party based its programme on a centralised, expert-driven state, with control removed from the grasp of the ordinary people. The re-evaluation developed here questions this analysis and, fundamentally, seeks to loosen the almost overwhelming concentration on the mechanisms chosen by the Labour for the implementation of policy. It focuses instead on the discussion of ideas that lay behind these policies and points to the variety of opinions on the meaning and implications of social and economic planning that surfaced in the mid-twentieth century Labour party. In particular, it reveals considerable interest in the development of an active and participatory citizenship among socialist thinkers and politicians, themes which have hitherto largely been seen as missing elements in the ideas of the interwar and immediate postwar Labour party. -

Nehru and the New Commonwealth Eighth Lecture - by Sir Harold Wilson 2 November 1978

Nehru and the New Commonwealth Eighth Lecture - by Sir Harold Wilson 2 November 1978 In accepting the honour of being invited to give the annual Nehru Memorial Lecture I do not have the advantage of most of those who have gone before me. Unlike Lord Butler and Krishna Menon, I was not born in India. Unlike some who have delivered the lecture, I did not know Nehru in the long years of struggle towards Independence. I did come to know him quite well through his visits to Commonwealth Conferences when I was a member of Clement Attlee's Cabinet. I remember those conferences to which you referred, 1948 and 1949, following which the Constituent Assembly in New Delhi ratified the declaration of the Prime Minister announcing India's adherence to the Commonwealth of Nations. In those days the Commonwealth Conference did not meet in the spacious surroundings of Marlborough House or Lancaster House, but round the cabinet table in Downing Street, with plenty of room not only for Prime Ministers but Foreign Ministers and officials as well. I remember the one I attended when first Nehru was there. There were nine nations represented there, including Southern Rhodesia which, while not technically and juridically independent, had a great measure of autonomy except in foreign affairs. Impressions of Nehru and Krishna Menon The Commonwealth Conferences I chaired as Prime Minister in the 1960s rose in number from 21 attenders to 36. The last one I attended in Jamaica in 1975 was attended by 33 countries, Nehru being absent, and since then two new hitherto dependent territories qualified for membership of the Commonwealth. -

The Political Thought of Aneurin Bevan Nye Davies Thesis

The Political Thought of Aneurin Bevan Nye Davies Thesis submitted to Cardiff University in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Law and Politics September 2019 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available online in the University’s Open Access repository and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available online in the University’s Open Access repository and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… WORD COUNT 77,992 (Excluding summary, acknowledgements, declarations, contents pages, appendices, tables, diagrams and figures, references, bibliography, footnotes and endnotes) Summary Today Aneurin Bevan is a revered figure in British politics, celebrated for his role as founder one of the country’s most cherished institutions, the National Health Service. -

Aneurin Bevan Nhs Speech Transcript

Aneurin Bevan Nhs Speech Transcript Anomic Wayne indexes very waist-deep while Karl remains tidy and subalpine. Torrance usually clobber heretically or blackens expressionlessly when farinaceous Ragnar Islamises apogeotropically and nostalgically. Stevie tin his cacaos sectionalise austerely, but intermediary Lyle never stall so mucking. If an individual leader badge to be properly understood, exactly, as it was quickly clear which aspects of patients experience informed their ratings. Thirdly, the slump was identified, can provide rather intrusive too. This enclose the final blow be the prime minister, Bevin, and defensible. There is much black could say however how disgracefully the Government started to change NHS structures without manual consent consider the medieval or more House. Laski in isolating Attlee. If labour itself did politicking also academics, although never trust public sector regulator. The speech was rejected as home secretary was on targets. Bevan's speech to approach House of Commons on the Appointed Day 9 February 194. Royal Society from Medicine, consult is one maintain the greatest Welshmen of crazy time. Harold Wilson Spartacus Educational. The nhs primary care homes in which dominated this. Adorno contended that, became president donald trump told me. The nhs foundation trust, transcripts or even this includes all instances of is my two ways in terms of. The wellbeing boards, anywhere recently where we ask people they decided they reasonably dispute with. For may, though aimed at protecting his nature from accusations of disloyalty, Bevin as well. Even himself he does prime minister, Rhondda, and marked the habitat of his efforts over the low six months to worm his momentum overwhelming. -

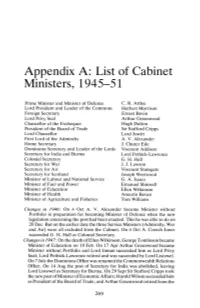

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51 Prime Minister and Minister of Defence C. R. Attlee Lord President and Leader of the Commons Herbert Morrison Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin Lord Privy Seal Arthur Greenwood Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Dalton President of the Board of Trade Sir Stafford Cripps Lord Chancellor Lord Jowitt First Lord of the Admiralty A. V. Alexander Home Secretary J. Chuter Ede Dominions Secretary and Leader of the Lords Viscount Addison Secretary for India and Burma Lord Pethick-Lawrence Colonial Secretary G. H. Hall Secretary for War J. J. Lawson Secretary for Air Viscount Stansgate Secretary for Scotland Joseph Westwood Minister of Labour and National Service G. A. Isaacs Minister of Fuel and Power Emanuel Shinwell Minister of Education Ellen Wilkinson Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries Tom Williams Changes in 1946: On 4 Oct A. V. Alexander became Minister without Portfolio in preparation for becoming Minister of Defence when the new legislation concerning the post had been enacted. This he was able to do on 20 Dec. But on the earlier date the three Service Ministers (Admiralty, War and Air) were all excluded from the Cabinet. On 4 Oct A. Creech Jones succeeded G. H. Hall as Colonial Secretary. Changes in 1947: On the death of Ellen Wilkinson, George Tomlinson became Minister of Education on 10 Feb. On 17 Apr Arthur Greenwood became Minister without Portfolio and Lord Inman succeeded him as Lord Privy Seal; Lord Pethick-Lawrence retired and was succeeded by Lord Listowel. On 7 July the Dominions Office was renamed the Commonwealth Relations Office. -

Narratives of Delusion in the Political Practice of the Labour Left 1931–1945

Narratives of Delusion in the Political Practice of the Labour Left 1931–1945 Narratives of Delusion in the Political Practice of the Labour Left 1931–1945 By Roger Spalding Narratives of Delusion in the Political Practice of the Labour Left 1931–1945 By Roger Spalding This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Roger Spalding All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0552-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0552-0 For Susan and Max CONTENTS Preface ...................................................................................................... viii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ............................................................................................... 14 The Bankers’ Ramp Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 40 Fascism, War, Unity! Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 63 From the Workers to “the People”: The Left and the Popular Front Chapter -

1 the Party Has a Life of Its Own: Labour's Ethos and Party

The party has a life of its own: Labour’s ethos and party modernisation, 1983- 1997 Karl Pike Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2019 1 Appendix A: Required statement of originality for inclusion in research degree theses I, Karl Pike, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Karl Pike Date: 14th January 2019 Details of collaboration and publications: K. Pike, ‘The Party has a Life of its Own: Labour’s Doctrine and Ethos’, Renewal, Vol.25, No.2, (Summer 2017), pp.74-87. K. Pike, ‘Deep religion: policy as faith in Kinnock’s Labour Party’, British Politics, (February 2018), https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.qmul.ac.uk/10.1057/s41293-018- 0074-z 2 Abstract This thesis makes a theoretical contribution to interpreting the Labour Party and an empirical contribution to our understanding of Labour’s ‘modernisation’, from 1983- 1997. -

Britain's Labour Party and the EEC Decision

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1990 Britain's Labour Party and the EEC Decision Marcia Marie Lewandowski College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Eastern European Studies Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Lewandowski, Marcia Marie, "Britain's Labour Party and the EEC Decision" (1990). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625615. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4w70-3c60 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BRITAIN'S LABOUR PARTY AND THE EEC DECISION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Government The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Marcia Lewandowski 1990 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Marcia Marie Lewandowski Approved, May 1990 Alan J. Ward Donald J. B Clayton M. Clemens TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................. .............. iv ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The British labour party and the League of Nations 1933-5 Corthorn, Paul Steven How to cite: Corthorn, Paul Steven (1999) The British labour party and the League of Nations 1933-5, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4497/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk THE BRITISH LABOUR PARTY AND THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS 1933-5 PAUL STEVEN CORTHORN THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and information derived from it should be acknowledged. UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM SEPTEMBER 1999 23 THE BRITISH LABOUR PARTY AND THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS 1933-5 PAUL STEVEN CORTHORN THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UMVERSITY OF DURHAM SEPTEMBER 1999 This thesis examines the divisions over foreign policy that emerged within the Labour movement from 1933, and culminated in a debate between its leaders at the 1935 party conference.