Arxiv:2004.07240V1 [Astro-Ph.CO] 15 Apr 2020 Towards Constant Behavior on Large Scales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ngc Catalogue Ngc Catalogue

NGC CATALOGUE NGC CATALOGUE 1 NGC CATALOGUE Object # Common Name Type Constellation Magnitude RA Dec NGC 1 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:07:16 27:42:32 NGC 2 - Galaxy Pegasus 14.2 00:07:17 27:40:43 NGC 3 - Galaxy Pisces 13.3 00:07:17 08:18:05 NGC 4 - Galaxy Pisces 15.8 00:07:24 08:22:26 NGC 5 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:07:49 35:21:46 NGC 6 NGC 20 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 7 - Galaxy Sculptor 13.9 00:08:21 -29:54:59 NGC 8 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:08:45 23:50:19 NGC 9 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.5 00:08:54 23:49:04 NGC 10 - Galaxy Sculptor 12.5 00:08:34 -33:51:28 NGC 11 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.7 00:08:42 37:26:53 NGC 12 - Galaxy Pisces 13.1 00:08:45 04:36:44 NGC 13 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.2 00:08:48 33:25:59 NGC 14 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.1 00:08:46 15:48:57 NGC 15 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.8 00:09:02 21:37:30 NGC 16 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:04 27:43:48 NGC 17 NGC 34 Galaxy Cetus 14.4 00:11:07 -12:06:28 NGC 18 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:09:23 27:43:56 NGC 19 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:10:41 32:58:58 NGC 20 See NGC 6 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 21 NGC 29 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 22 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.6 00:09:48 27:49:58 NGC 23 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:53 25:55:26 NGC 24 - Galaxy Sculptor 11.6 00:09:56 -24:57:52 NGC 25 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.0 00:09:59 -57:01:13 NGC 26 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:10:26 25:49:56 NGC 27 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.5 00:10:33 28:59:49 NGC 28 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.8 00:10:25 -56:59:20 NGC 29 See NGC 21 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 30 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:10:51 21:58:39 -

Selecting an Award to Write Page 1 of 7 Leadership Awards 1, 2, and 3 Are Judged by an Anonymous Committee Appointed by the FFGC President

How to Select a FFGC Award to write from your Garden Club’s Programs or Events Valerie Seinfeld Civic Awards ? Horticulture ? Community Projects/ Historical ? Flower Show Achievement Awards ? Conservation ? Leadership ? District Awards ? Tree Planting ? Publications & Social Media ? Junior Gardening ? Landscaping ? Miscellaneous Awards ? Special Achievement ? How to Select which FFGC Award to write from your Garden Club’s Programs or Events www.ffgc.org Members Tab - click to drop down and Awards is first. Check back often as new awards may be added each year. Begin by looking at the Category the award falls under. Read it in detail. Does your program or event meet the criteria? This handy document will give you an idea before you go to the computer if there is an award title that matches your program or event. Once you decide on an award to write, download the application form and fill out the top portion. Save it for later when you are ready to start. But Not ALL: Remember most awards, but not all, are due at the same time. Most are sent to the same place, but not all. Most are attention to the Awards Chair, but not all. Make note of exceptions. Reread the award description in detail. Give the Chair of the Program or Event a list of items you need to complete the Award. Ex. Pictures before and after, Budget and where the money came from. How many were involved in this award, all members, percentage of members, community members? Valerie Seinfeld Selecting an Award to Write page 1 of 7 Leadership Awards 1, 2, and 3 are judged by An Anonymous Committee appointed by the FFGC President. -

Appendix a Planning an Astrophotography Imaging Session

Appendix A Planning an Astrophotography Imaging Session One way to obtain a high percentage of successful photographs is to look at imaging a deep space object as a project. The first step of any project is to define the project’s goals and objectives followed by detailed planning and then executing the plan. Perhaps the best way to explain an astrophotography project is by an example. For our example, let’s assume a location at 38° north latitude in a suburban area with moderate levels of light pollution with a skyglow of magnitude 19 per arcsec- ond squared. The imaging kit is an Orion ST-80A 80 mm f/5 refractor, a Canon EOS T3/1100D camera with an interval timer and a Celestron 4 SE mount on a wedge. The current time of the year is early summer and we see an image of the galaxy NGC 2403 posted by someone on an internet forum, in an astronomy maga- zine, etc. The galaxy looks interesting and we decide that we would like to make our own image of it. Before getting heavily involved in planning we need answers to the following questions: • Is the galaxy visible at our viewing location? • When is the optimum time to photograph the galaxy? • Is our equipment capable of capturing a decent image of NGC 2403? The literature tells us that NGC 2403 has an apparent magnitude 8.4, an apparent size of 21.4 × 10.7 arcminutes, and is located in the Constellation Camelopardalis. It is object number 7 in the Caldwell list for small telescopes and is often observed with a pair of binoculars. -

Comparative Plant Resistance in Fifty-Five Tea Accessions, Camellia Sinensis L., in Ibadan, South West, Nigeria

Plant resistance of Camellia sinensis L ( Coleoptera: JBiopest 10(2):146-153 (2017) ComparativeChrysomelidae: plant Bruchinae) resistance in fifty-five tea accessions, Camellia sinensis L., in Ibadan, South West, Nigeria O. M.Azeez ABSTRACT Fifty five accessions comprising both local and exotic clones were assessed for their resistance to field pest at Abarakata farm, CRIN. The accessions derived from Mambilla plateau, CRIN out-station, Taraba State were screened for resistance to infestation by leaf defoliators. Results revealed that there were significant differences among the accessions in terms of the number of holes on the leaf and plant damage both in the dry and raining season. On NGC15, NGC17, NGC19, C235, C357 tea clones recorded less number of holes and total damage of leaves and thus considered highly resistant to field insect pests. Based on the rating, clones NGC 8, NGC12, NGC14, NGC24, NGC27, NGC40, NGC41, NGC42,NGC49, NGC50,NGC51, C68, C270,C318, C359, C377 were significantly resistant to the insect infestations, while NGC18, NGC22, NGC23,NGC25, NGC26, NGC29, NGC35,NGC47, NGC48, NGC53, NGC54, NGC55, C61, C136, C143, C228, C236, C327, C353, C354, C369, C370 were moderately resistant. NGC13, NGC32, NGC37, NGC38, NGC45, NGC46, C56, C74, C108, C363, C367 and C368 were the most susceptible with the highest damage indices values (P<0.05). The range of each of the resistance indices measured in the susceptible clones in both dry and wet season were number of leaf damage (43-51)(37-46), number of leaf holes (18-19)(16-20). Keywords: Clones; tea; resistance; damage; susceptible MS History: 16.10.2017 (Received)-27.11.2017 (Revised)-3.12.2017 (Accepted). -

Minterrornews.Com Special Edition 2006 the Best of Mint Error News

TM minterrornews.com Special Edition 2006 The Best of Mint Error News A Mike Byers Publication Byers Numismatic Corp mikebyers.com TM The Largest Dealer of the World’s Rarest Mint Errors U.S. & World Major Mint Errors • Die Trials • Numismatic Rarities Unique SPECIMEN Silver 1920 SL 25¢ 1838 $5 Die Trial Splasher Certificate Set of 16 Struck on Peru 20C Planchet J-A1838-6 PCGS Certified NGC MS 60 FH Unique PCGS MS 65 UNIQUE Unique 1866 $2½ Struck on a 3 Cent Pair of Indian Head 1¢ Die Caps Barber Half Nickel Planchet Obverse & Reverse Full Obverse Brockage NGC MS 66 PCGS MS 64 PCGS AU 58 UNIQUE Unique Set of Four 1921-S Morgan Dollar 1895-O Barber Dime Paraguay Gold Overstrikes Struck 45% Off-Center Obverse Die Cap NGC Certified NGC MS 63 PCGS MS 64 1846 J-110A $5 Obv Die Trial 1924 SL 25¢ 1862 Indian Head 1¢ Struck on $2½ Trial Double Struck Deep Obverse Die Cap NGC MS 65 BN ANACS AU 55 PCGS MS 62 Unique Set of Three 1887 $3 Indian Gold Proof 1942 Walking Liberty 50¢ Paraguay Gold Overstrikes Triple Struck Struck on Silver 25¢ Planchet NGC Certified PCGS PR 63 PCGS MS 65 Unique Jefferson Nickel 1802/1 $5 Draped Bust Gold 1865 2¢ Die Trial Triple Struck Obverse Deep Obverse Die Cap PCGS Certified ANACS EF 45 & Brockage 1804 $2½ Capped Bust To Right 1898 Barber 25¢ 1945-S WL 50¢ Double Struck Obverse Die Cap & Brockage Struck on El Salvador 25¢ Planchet NGC Fine 15 PCGS MS 62 NGC MS 63 UNQUE 1806 $5 Capped Bust Triple Struck 1865 $1 Indian Gold Proof 1920 Buffalo Nickel Rotated 90° Triple Struck Reverse Struck on Copper Planchet PCGS AU 50 PCGS PR 64 Cameo NGC AU 55 UNIQUE 1874 $1 U.S. -

2012 Tour of Anchorage Final Standings

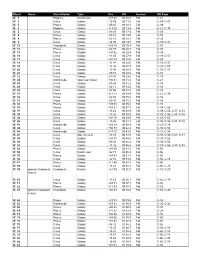

2012 Tour of Anchorage - Final GC after Stage 5 Sheryl Loan wins her record ninth Tour of Anchorage! Overall Place Bib Deficit Time Beginner Men 1 318 Clinton Hodges III Beginner Men 3:41:03 2 327 Norm Sharp Beginner Men 3:41:08 0:00:05 3 319 Peter Malecha Beginner Men 3:41:41 0:00:38 4 320 Tom Schultz Beginner Men 3:48:14 0:07:11 5 325 Eric Anderson Beginner Men 3:48:28 0:07:25 6 302 Michael Fischetti Alaska Velo Sport Beginner Men 3:49:51 0:08:48 7 313 John Lynn Beginner Men 3:50:39 0:09:37 8 364 Steve Kiefer Beginner Men 3:54:05 0:13:02 9 396 Charles Lowell Kaladi-Subway Beginner Men 3:58:09 0:17:06 10 316 Vispi Mistry Beginner Men 4:09:54 0:28:52 11 2 Gunnar Knapp Beginner Men 4:13:46 0:32:43 12 307 Ryan McLaughlin Beginner Men 4:19:00 0:37:57 13 311 Andrew Block Beginner Men 4:25:13 0:44:10 14 305 Gregory Lemons Beginner Men 4:32:33 0:51:30 15 335 Jonathan Woodman Beginner Men 4:41:06 1:00:03 NGC 396 Charles Lowell Kaladi-Subway Beginner Men NGC NGC NGC 338 Keenan Brownsberger Beginner Men NGC NGC NGC 308 Tim Thornleg Beginner Men NGC NGC NGC 329 Daniel McCarthy Beginner Men NGC NGC NGC 333 Mike Shiffer Beginner Men NGC NGC NGC 331 Ben Applegate Beginner Men NGC NGC NGC 304 Jeffrey Campbell Beginner Men NGC NGC NGC 322 Marvin Colbert Speedway Cycles Beginner Men NGC NGC NGC 314 Andrew Cunningham Beginner Men NGC NGC NGC 310 Karl Krenz Beginner Men NGC NGC NGC 303 Peter Mejia Beginner Men NGC NGC NGC 337 Patrick Murray Beginner Men NGC NGC NGC 328 Brett Shepard Beginner Men NGC NGC NGC 330 David Stamp Beginner Men NGC NGC Beginner Women -

HB-NGC Index

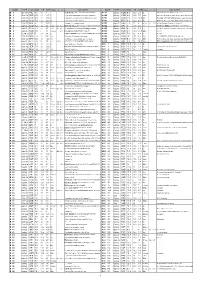

Object Name Constellation Type Dec RA Season HB Page IC 1 Pegasus Double star +27 43 00 08.4 Fall C-21 IC 2 Cetus Galaxy -12 49 00 11.0 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 3 Pisces Galaxy -00 25 00 12.1 Fall C-39 IC 4 Pegasus Galaxy +17 29 00 13.4 Fall C-21, C-39 IC 5 Cetus Galaxy -09 33 00 17.4 Fall C-39 IC 6 Pisces Galaxy -03 16 00 19.0 Fall C-39 IC 8 Pisces Galaxy -03 13 00 19.1 Fall C-39 IC 9 Cetus Galaxy -14 07 00 19.7 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 10 Cassiopeia Galaxy +59 18 00 20.4 Fall C-03 IC 12 Pisces Galaxy -02 39 00 20.3 Fall C-39 IC 13 Pisces Galaxy +07 42 00 20.4 Fall C-39 IC 16 Cetus Galaxy -13 05 00 27.9 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 17 Cetus Galaxy +02 39 00 28.5 Fall C-39 IC 18 Cetus Galaxy -11 34 00 28.6 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 19 Cetus Galaxy -11 38 00 28.7 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 20 Cetus Galaxy -13 00 00 28.5 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 21 Cetus Galaxy -00 10 00 29.2 Fall C-39 IC 22 Cetus Galaxy -09 03 00 29.6 Fall C-39 IC 24 Andromeda Open star cluster +30 51 00 31.2 Fall C-21 IC 25 Cetus Galaxy -00 24 00 31.2 Fall C-39 IC 29 Cetus Galaxy -02 11 00 34.2 Fall C-39 IC 30 Cetus Galaxy -02 05 00 34.3 Fall C-39 IC 31 Pisces Galaxy +12 17 00 34.4 Fall C-21, C-39 IC 32 Cetus Galaxy -02 08 00 35.0 Fall C-39 IC 33 Cetus Galaxy -02 08 00 35.1 Fall C-39 IC 34 Pisces Galaxy +09 08 00 35.6 Fall C-39 IC 35 Pisces Galaxy +10 21 00 37.7 Fall C-39, C-56 IC 37 Cetus Galaxy -15 23 00 38.5 Fall C-39, C-56, C-57, C-74 IC 38 Cetus Galaxy -15 26 00 38.6 Fall C-39, C-56, C-57, C-74 IC 40 Cetus Galaxy +02 26 00 39.5 Fall C-39, C-56 IC 42 Cetus Galaxy -15 26 00 41.1 Fall C-39, C-56, C-57, C-74 IC -

Hickson Compact Groups

Hickson Catalog of Compact Groups of Galaxies A Complete Observing Guide of All 100 Groups Reiner Vogel 2009 Finder charts measure 20° (with 5° circle) and 4° (with 1° circle) and were made with Cartes du Ciel by Patrick Chevalley (http://www.stargazing.net/astropc/) using a catalog generated by Martin Schönball (http://www.schoenball.de/) Images are DSS Images (blue plates, POSS II or SERCJ) and measure 20’ by 20’ (http://archive.stsci.edu/cgi- bin/dss_plate_finder) DSS images copyright notice: The Digitized Sky Survey was produced at the Space Telescope Science Institute under U.S. Government grant NAG W-2166. The images of these surveys are based on photographic data obtained using the Oschin Schmidt Telescope on Palomar Mountain and the UK Schmidt Telescope. The plates were processed into the present compressed digital form with the permission of these institutions. Galaxy Data are from Paul Hickson’s webpage (http://www.astro.ubc.ca/people/hickson/), coordinates 1950.0, and CDS (http://cdsweb.u-strasbg.fr) Group data are based on Paul Hickson’s original data, group coordinates were transformed to 2000 using Cartes du Ciel, visual magnitudes are from Miles Paul's compilation (available on Jim Shield’s webpage http://www.astronomy-mall.com/Adventures.In.Deep.Space/hickcatalog.htm) A selection of the 32 most interesting Hickson Groups also for smaller telescopes can be found on http://www.astronomy-mall.com/Adventures.In.Deep.Space/hicklist.htm). Downloaded at www.reinervogel.net Complete List of Groups HCG Const RA (2000) Dec brightest -

Investigating the Break in the Cepheid Period-Luminosity Relation and Its Implications

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2005 Investigating the break in the Cepheid period-luminosity relation and its implications. Chow-Choong, Ngeow University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Ngeow, Chow-Choong,, "Investigating the break in the Cepheid period-luminosity relation and its implications." (2005). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2004. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2004 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVESTIGATING THE BREAK IN THE CEPHEID PERIOD-LUMINOSITY RELATION AND ITS IMPLICATIONS A Dissertation Presented by CHOW-CHOONG NGEOW Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2005 Department of Astronomy © Copyright by Chow-Choong Ngeow All Rights Reserved INVESTIGATING THE BREAK IN THE CEPHEID PERIOD-LUMINOSITY RELATION AND ITS IMPLICATIONS A Dissertation Presented by CHOW-CHOONG NGEOW Approved as to style and content by: Shashi Kanbur, Chair Ron Snell, Department Chair Department of Astronomy / dedicate this Thesis Dissertation to my parents, Yin-Ngee Ngeow & Chiew-Hong Lim, and to my girl friend, Judy Chen. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to ax^knowledge my advisor, Prof. Shashi Kanbur, for the teaching, guidance, assis- tance, support and encouragement through out my work in this Thesis Dissertation for the past 5 years. -

Variability Analysis of Some Genotypes in Nigeria Tea (Camellia Sinensis) Germplasm

Variability analysis of some genotypes in Nigeria tea (Camellia sinensis) germplasm Olayinka Olufemi Olaniyi 1, Olusola Babatunde Kehinde 2, Amos Adegbola Oloyede 1, Omotayo Olalekan Adenuga 1, Kayode Olufemi Ayegboyin 1, Elizabeth Folasade Mapayi 1, Mohammed Baba Nitsa 1, Feyisetan Omolola Sulaimon 1, * and Tope Emmanuel Ebunola 1 1 Crop Improvement Division, Cocoa Research Institute of Nigeria. 2 Federal University of Agriculture Abeokuta, Nigeria. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 2021, 09(01), 050–061 Publication history: Received on 18 December 2020; revised on 27 December 2020; accepted on 29 December 2020 Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.30574/wjarr.2021.9.1.0491 Abstract Thirty four tea clones were sourced from Cocoa Research Institute of Nigeria tea germplasm and raised through stem cuttings for 10 months in the nursery. The experiment was laid out in a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with 3 replications in 2016. Agronomic and yield data were collected and subjected to analysis of variance. Single linkage cluster analysis (SLCA), principal component analysis (PCA) and FATCLUS analysis were employed to analyse the data. ANOVA showed considerable significant variation p<0.05 among the 34 tea genotypes. The PCA showed that Plant Height (PH) 0.39, Number of Leaves (NL) 0.38, Number of Branches (NB) 0.37, Harvestable Points (HP) 0.31, Stem Diameter 0.39 and Leaf Breadth 0.30 accounted for most of the variations observed. Axes 1, 2 and 3 of the PCA accounted for 37.23%, 15.48% and 10.75% variability respectively with cumulative value of 63.47%. The genotypes were clustered into 7 groups by FASTCLUS Analysis. -

7000 List by Name

NAME TYPE CON MAG S.B. SIZE Class ns bs SAC NOTES NAME TYPE CON MAG S.B. SIZE Class ns bs SAC NOTES M 1 SN Rem TAU 8.4 11 8' Crab Nebula; filaments;pulsar 16m;3C144 -M 99 Galaxy COM 9.9 13.2 5.3' Sc SN 1967h;Norton-diff for small scope M 2 Glob CL AQR 6.5 11 11.7' II Lord Rosse-Dark area near core;* mags 13... -M 100 Galaxy COM 9.4 13.4 7.5' SBbc SN 1901-14-59;NGC 4322 @ 5.2';NGC 4328 @ 6.1' M 3 Glob CL CVN 6.3 11 18.6' VI Lord Rosse-sev dark marks within 5' of center -M 101 Galaxy UMA 7.9 14.9 28.5' SBc P w NGC 5474;SN 1909;spir galax w one heavy arm; M 4 Glob CL SCO 5.4 12 26.3' IX Look for central bar structure -M 102 Galaxy DRA 9.9 12.2 6.5' Sa vBN w dk lane and ansae;NGC 5867 small E neb; M 5 Glob CL SER 5.7 11 19.9' V st mags 11...;superb cluster -M 103 Opn CL CAS 7.4 11 6' III 2 p 40 10.6 in Cas OB8;incl Struve 131 6-9m 14'' M 6 Opn CL SCO 4.2 10 20' III 2 p 80 6.2 Butterfly cluster;51 members to 10.5 mag incl var*- BMM104 Sco Galaxy VIR 8 11.6 8.6' Sab Sombrero Galaxy; H I 43;dark equatorial lane; M 7 Opn CL SCO 3.3 12 80' II 2 r 80 5.6 80 members to 10th mag; Ptolemy's cluster -M 105 Galaxy LEO 9.3 12.8 5.3' E1 P w NGC 3384 @ 7.2';NGC 3389 @ 10 ';Leo Group M 8 Opn CL SGR 4.6 - 15' II 2 m n 6.9 In Lagoon nebula M8;25* mags 7..