The Lincoln Enigma: the Changing Faces of an American Icon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lincoln Studies at the Bicentennial: a Round Table

Lincoln Studies at the Bicentennial: A Round Table Lincoln Theme 2.0 Matthew Pinsker Early during the 1989 spring semester at Harvard University, members of Professor Da- vid Herbert Donald’s graduate seminar on Abraham Lincoln received diskettes that of- fered a glimpse of their future as historians. The 3.5 inch floppy disks with neatly typed labels held about a dozen word-processing files representing the whole of Don E. Feh- renbacher’s Abraham Lincoln: A Documentary Portrait through His Speeches and Writings (1964). Donald had asked his secretary, Laura Nakatsuka, to enter this well-known col- lection of Lincoln writings into a computer and make copies for his students. He also showed off a database containing thousands of digital note cards that he and his research assistants had developed in preparation for his forthcoming biography of Lincoln.1 There were certainly bigger revolutions that year. The Berlin Wall fell. A motley coalition of Afghan tribes, international jihadists, and Central Intelligence Agency (cia) operatives drove the Soviets out of Afghanistan. Virginia voters chose the nation’s first elected black governor, and within a few more months, the Harvard Law Review selected a popular student named Barack Obama as its first African American president. Yet Donald’s ven- ture into digital history marked a notable shift. The nearly seventy-year-old Mississippi native was about to become the first major Lincoln biographer to add full-text searching and database management to his research arsenal. More than fifty years earlier, the revisionist historian James G. Randall had posed a question that helps explain why one of his favorite graduate students would later show such a surprising interest in digital technology as an aging Harvard professor. -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven. -

HI 2108 Reading List

For students of HI 2106 – Themes in modern American history and HI 2018 – American History: A survey READING LISTS General Reading: 1607-1991 Single or two-volume overviews of American history are big business in the American academic world. They are generally reliable, careful and bland. An exception is Bernard Bailyn et al, The Great Republic: a history of the American people which brings together thoughtful and provocative essays from some of America’s top historians, for example David Herbert Donald and Gordon Wood. This two-volume set is recommended for purchase (and it will shortly be available in the library). Other useful works are George Tindall, America: a Narrative History, Eric Foner, Give me Liberty and P.S. Boyer et al, The Enduring Vision all of which are comprehensive, accessible up to date and contain very valuable bibliographies. Among the more acceptable shorter alternatives are M.A. Jones, The Limits of Liberty and Carl Degler, Out of our Past. Hugh Brogan, The Penguin history of the United States is entertaining and mildly idiosyncratic. A recent highly provocative single- volume interpretative essay on American history which places war at the centre of the nation’s development is Fred Anderson and Andrew Cayton, The Dominion of War: Empire and Liberty in North America, 1500-2000 All of the above are available in paperback and one should be purchased. Anthologies of major articles or extracts from important books are also a big commercial enterprise in U.S. publishing. By far the most useful and up-to-date is the series Major problems in American History published by D.C. -

A NEW BIRTH of FREEDOM: STUDYING the LIFE of Lincolnabraham Lincoln at 200: a Bicentennial Survey

Civil War Book Review Spring 2009 Article 3 A NEW BIRTH OF FREEDOM: STUDYING THE LIFE OF LINCOLNAbraham Lincoln at 200: A Bicentennial Survey Frank J. Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Williams, Frank J. (2009) "A NEW BIRTH OF FREEDOM: STUDYING THE LIFE OF LINCOLNAbraham Lincoln at 200: A Bicentennial Survey," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 11 : Iss. 2 . Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol11/iss2/3 Williams: A NEW BIRTH OF FREEDOM: STUDYING THE LIFE OF LINCOLNAbraham Linco Feature Essay Spring 2009 Williams, Frank J. A NEW BIRTH OF FREEDOM: STUDYING THE LIFE OF LINCOLNAbraham Lincoln at 200: A Bicentennial Survey. No president has such a hold on our minds as Abraham Lincoln. He lived at the dawn of photography, and his pine cone face made a haunting picture. He was the best writer in all American politics, and his words are even more powerful than his images. His greatest trial, the Civil War, was the nation’s greatest trial, and the race problem that caused it is still with us today. His death by murder gave his life a poignant and violent climax, and allows us to play the always-fascinating game of “what if?" Abraham Lincoln did great things, greater than anything done by Theodore Roosevelt or Franklin Roosevelt. He freed the slaves and saved the Union, and because he saved the Union he was able to free the slaves. Beyond this, however, our extraordinary interest in him, and esteem for him, has to do with what he said and how he said it. -

Book by Linda Heywood and John Thornton Wins African Studies Prize

December 2008 Book by Linda Heywood and John Thornton wins African Studies prize he annual meeting of the African Studies Association, held in Chicago No- vember 13-16, had as its theme “Knowledge of Africa: The Next Fifty Years.” On November 11 graduate student It is at this event that the winner of the annual Melville J. Herskovits Award T Michael McGuire traveled to Smith is announced, the most important book award in the field of African Studies. Last College, where he addressed an under- year’s winner was Barbara Cooper of Rutgers University (PhD from Boston Univer- graduate seminar studying the Smith sity in 1993). College Relief Unit (one of the non- At the awards ceremony on November 14, the Association revealed that this governmental organizations, or year’s winners were Professors Linda Heywood and John Thornton of Boston Uni- NGOs, his dissertation examines). En- versity for their jointly authored book, Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the titled “Allies Yet Adversaries: The Foundation of the Americas, 1585-1660 (Cambridge University Press, 2007); a third Smith Unit and Its Organizational In- winner was Professor Parker Shipton of BU’s Anthropology Department. teractions in France,” it briefly covered The Heywood-Thornton book narrates the making of a Creole Atlantic world. It the complementary and competitive tells the story of the formative period of African American culture when Angolans relations the Smith Unit had with the were brought to the New Worldthrough the slave trade to Portuguese, English, and French government and several French Dutch colonies. The authors represent various Angolan kingdoms as culturally di- and American NGOs as the Unit verse and changing and show the attitudes of Europeans to the continental Afri- helped reconstruct sixteen devastated cans changing as they encountered African political, religious, cultural, and mili- villages in the Somme region. -

For the People

ForFor thethe PeoplePeople A Ne w s l e t t e r of th e Ab r a h a m Li n c o l n As s o c i a t i o n Volume 2, Number 4 Winter, 2000 Springfield, Illinois Abraham Lincoln Association Endowment Progress by Dr. Robert S. Eckley This may provide an enhancement in Committee are Robert S. Eckley, current income. Chairman, Judith Barringer, Treasurer, he new Abraham Lincoln Assistance is available in gift ALA, Donald H. Funk, Richard E. Association Endowment Fund design from any members of the ALA Hart, Vice President, ALA, and Fred Tis nearing the end of its first full Endowment Committee who are will- B. Hoffmann, and they may be con- year with contributions from ten ing to work with prospective donors tacted through the ALA address at donors. An endowment procedure is or their legal counsel. The Association One Old State Capitol Plaza, in place, and the initial investment board members who serve on this Springfield, IL 62701. placements have been made. We invite all ALA members and friends to con- sider gifts that will enable it to fulfill the Association’s stated mission when Make Your Reservations Now established in Springfield in 1908 to prepare for the centennial of Lincoln’s for February 12 birth. The purpose of the endowment is to strengthen the financial resources of ark your calendars now for sium is “Abraham Lincoln, History, the ALA and to assist in its budgetary February 12. In addition to and the Millennium.” The speakers and planning functions. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Art and Life in America by Oliver W. Larkin Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum | Bush-Reisinger Museum | Arthur M

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Art and Life in America by Oliver W. Larkin Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum | Bush-Reisinger Museum | Arthur M. Sackler Museum. In this allegorical portrait, America is personified as a white marble goddess. Dressed in classical attire and crowned with thirteen stars representing the original thirteen colonies, the figure gives form to associations Americans drew between their democracy and the ancient Greek and Roman republics. Like most nineteenth-century American marble sculptures, America is the product of many hands. Powers, who worked in Florence, modeled the bust in plaster and then commissioned a team of Italian carvers to transform his model into a full-scale work. Nathaniel Hawthorne, who visited Powers’s studio in 1858, captured this division of labor with some irony in his novel The Marble Faun: “The sculptor has but to present these men with a plaster cast . and, in due time, without the necessity of his touching the work, he will see before him the statue that is to make him renowned.” Identification and Creation Object Number 1958.180 People Hiram Powers, American (Woodstock, NY 1805 - 1873 Florence, Italy) Title America Other Titles Former Title: Liberty Classification Sculpture Work Type sculpture Date 1854 Places Creation Place: North America, United States Culture American Persistent Link https://hvrd.art/o/228516 Location Level 2, Room 2100, European and American Art, 17th–19th century, Centuries of Tradition, Changing Times: Art for an Uncertain Age. Signed: on back: H. Powers Sculp. Henry T. Tuckerman, Book of the Artists: American Artist Life, Comprising Biographical and Critical Sketches of American Artists, Preceded by an Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of Art in America , Putnam (New York, NY, 1867), p. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Benjamin Henry Latrobe by Talbot Faulkner Hamlin Benjamin Henry Latrobe by Talbot Faulkner Hamlin

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Benjamin Henry Latrobe by Talbot Faulkner Hamlin Benjamin Henry Latrobe by Talbot Faulkner Hamlin. Our systems have detected unusual traffic activity from your network. Please complete this reCAPTCHA to demonstrate that it's you making the requests and not a robot. If you are having trouble seeing or completing this challenge, this page may help. If you continue to experience issues, you can contact JSTOR support. Block Reference: #7fc8aa90-cf51-11eb-a8fa-33e0b1df654c VID: #(null) IP: 116.202.236.252 Date and time: Thu, 17 Jun 2021 09:50:50 GMT. Benjamin Henry Latrobe. Benjamin Henry Latrobe was born in 1764 at Fulneck in Yorkshire. He was the Second son of the Reverend Benjamin Latrobe (1728 - 86), a minister of the Moravian church, and Anna Margaretta (Antes) Latrobe (1728 - 94), a third generation Pennsylvanian of Moravian Parentage. The original Latrobes had been French Huguenots who had settled in Ireland at the end of the 17th Century. Whilst he is most noted for his work on The White House and the Capitol in Washington, he introduced the Greek Revival as the style of American National architecture. He built Baltimore cathedral, not only the first Roman Catholic Cathedral in America but also the first vaulted church and is, perhaps, Latrobes finest monument. Hammerwood Park achieves importance as his first complete work, the first of only two in this country and one of only five remaining domestic buildings by Latrobe in existence. It was built as a temple to Apollo, dedicated as a hunting lodge to celebrate the arts and incorporating elements related to Demeter, mother Earth, in relation to the contemporary agricultural revolution. -

2012 Legal Heritage of the Civil War Issue

NORTHERN KENTUCKY LAW REVIEW NORTHERN KENTUCKY LAW REVIEW Legal Heritage of the Volume 39 Number 4 Civil War Issue COPYRIGHT © NORTHERN KENTUCKY UNIVERSITY Cite as 39 N. KY. L. REV. (2012) Northern Kentucky Law Review is published four times during the academic year by students of Salmon P. Chase College of Law, Northern Kentucky University, Highland Heights, Kentucky 41099. Telephone: 859/572-5444. Facsimile: 859/572-6159. Member, National Conference of Law Reviews. All sections which appear in this issue are indexed by the H.W. Wilson Company in its Index to Legal Periodicals. Northern Kentucky Law Review articles are also available on microfilm and microfiche through University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Subscription rates are $35.00 per volume, $10.00 per individual issue. If a subscriber wishes to discontinue a subscription at its expiration, notice to that effect should be sent to the Northern Kentucky Law Review office. Otherwise, it will be assumed that renewal of the subscription is desired. Please send all manuscripts to the address given above. No manuscript will be returned unless return is specifically requested by the author. NORTHERN KENTUCKY LAW REVIEW Legal Heritage of the Volume 39 Number 4 Civil War Issue Editor-in-Chief NICHOLAS DIETSCH Executive Editor SEAN PHARR Managing Editors JESSICA KLINGENBERG HEATHER TACKETT PAUL WISCHER Student Articles Editors Lead Articles Editor COLBY COWHERD MARK MUSEKAMP JASON KINSELLA Symposium Editor Kentucky Survey Issue Editor JESSE SHORE JOSH MCINTOSH Administrative -

John/Vitae P. 1 RICHARD R. JOHN (Updated January 2020)

John/Vitae p. 1 RICHARD R. JOHN (updated January 2020) Columbia Journalism School 560 Riverside Drive 18 G Columbia University New York, NY 10027-3212 2950 Broadway New York, NY 10027 email: [email protected] (212) 854-0547 (o); (212) 854-7837 (fax) EDUCATION 1989 Ph.D. Harvard University History of American Civilization 1983 M.A. Harvard University History 1981 B.A. Harvard University Social Studies (magna cum laude) PRIMARY RESEARCH INTERESTS history of communications history of business, technology, and the state since 1700 political economy of communications BOOKS Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010; paperback, 2015; in print. Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1995; paperback, 1998; in print. DISSERTATION “Managing the Mails: The Postal System, Public Policy, and American Political Culture, 1823-1836” co- directed by Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., and David Herbert Donald HONORS Fellow, Guggenheim Foundation, 2019 Thomas S. Berry Lecture, University of Richmond, Richmond, Virginia, March 2018 Visiting Professor, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), Paris, spring 2016 Nanqiang Lecture, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China, May 2012 Visiting Professor, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), Paris, spring 2011 Ralph E. Gomory Prize for the best historical monograph on “the consequences of business activity,” Business History Conference -

PULITZER PRIZE WINNERS in LETTERS © by Larry James

PULITZER PRIZE WINNERS IN LETTERS © by Larry James Gianakos Fiction 1917 no award *1918 Ernest Poole, His Family (Macmillan Co.; 320 pgs.; bound in blue cloth boards, gilt stamped on front cover and spine; full [embracing front panel, spine, and back panel] jacket illustration depicting New York City buildings by E. C.Caswell); published May 16, 1917; $1.50; three copies, two with the stunning dust jacket, now almost exotic in its rarity, with the front flap reading: “Just as THE HARBOR was the story of a constantly changing life out upon the fringe of the city, along its wharves, among its ships, so the story of Roger Gale’s family pictures the growth of a generation out of the embers of the old in the ceaselessly changing heart of New York. How Roger’s three daughters grew into the maturity of their several lives, each one so different, Mr. Poole tells with strong and compelling beauty, touching with deep, whole-hearted conviction some of the most vital problems of our modern way of living!the home, motherhood, children, the school; all of them seen through the realization, which Roger’s dying wife made clear to him, that whatever life may bring, ‘we will live on in our children’s lives.’ The old Gale house down-town is a little fragment of a past generation existing somehow beneath the towering apartments and office-buildings of the altered city. Roger will be remembered when other figures in modern literature have been forgotten, gazing out of his window at the lights of some near-by dwelling lifting high above his home, thinking -

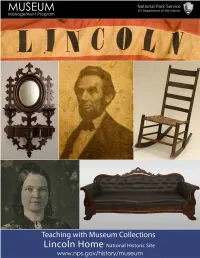

How to Write a Teaching with Museum Collections Lesson Plan

Lincoln- The Candidate: “The Taste is in My Mouth a Little” A. Header Title: Lincoln- The Candidate: “The Taste is in My Mouth a Little” Developed by: Diane Poe- Hazel Dell Elementary School, Springfield, IL George Gerrietts- South Pekin Grade School, South Pekin, IL Paula Shotwell- Iles Elementary School, Springfield, IL Grades 5-8 Number of Sessions and Length of lesson 7 sessions 30-45 minutes each Some projects may require additional time B. Overview of this Collection-Based Lesson Plan Park Name: Lincoln Home National Historic Site, Springfield Illinois Description: These activities focus on the political career of Abraham Lincoln from the Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858 to his election to the Presidency in 1860. Activity 1: Introduction and Warm Up - “How to Read an Object” Activity 2: The Lincoln-Douglas Debates Activity 3: Campaign for the Republican Nomination Activity 4: Campaigning from Home: March 14 – August 8, 1860 Activity 5: Campaign Materials Activity 6: Election of 1860 Activity 7: Campaign Project Essential question. What was the “pathway” by which Abraham Lincoln “traveled” to the Presidency of the United States? C. Museum Collections Used in this Lesson Plan Activity 1: LIHO 6723 – head 1 LIHO 6724 – right hand LIHO 6725 – left hand Activity 2: LIHO 927 – Political Debates of Lincoln & Douglas LIHO 928 – Political Text Book for 1860 Activity 3: LIHO 7328 - Lincoln Portrait from Cooper Union Activity 4: LIHO 5412 – Photograph of rally at Lincoln Home LIHO 1059 – Settee from Lincoln Home 2 LIHO 6760 – Abraham Lincoln’s Calling Card Activity 5: LIHO 6767 – Commemorative Token from 1864 Election LIHO 6768 – Commemorative Token from 1860 Election LIHO 7259 – 1860 Campaign Banner 3 Activity 6: LIHO 10304 – Republican Ticket from 1860 Election D.