Glenburn Precinct (Blocks 16, 30, 60, 71–73, and 94, Kowen)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cartography, Empire and Copyright Law in Colonial Australia Isabella

Cartography, Empire and Copyright Law in Colonial Australia Isabella Alexander Recent scholarship has established the centrality of maps and mapmaking to the imperial project, both as expressions of surveillance, spatial construction and control, as well as in the role maps played in making and supporting claims of property and ownership. Much less attention has been paid to the question of ownership in the map itself. This is important because the person, or entity, who owned the map could determine how the land depicted in the map was portrayed, and how access to that information was disseminated. It also affected how the map was perceived in terms of the authority, or accuracy, of its claims. This article examines several disputes that arose in colonial Australia over the ownership of maps, exploring how different interests arose and came into conflict in relation to their control, dissemination and commercialisation. It suggests that a consideration of these cases reveals the role that copyright law played as a technology of empire. Reading the history of colonial Australia, it is hard to escape the conclusion that ‘[o]ne way or another, almost everything about the history of the Australian colonies was about land’.1 It is a story of dispossession and possession: the indigenous inhabitants were dispossessed, so that the land could be possessed first by the Crown and then by private parties. Possession turned into ownership by operation of the laws that the new arrivals brought with them. But for land to be possessed and owned, it had to be known, and at the end of the eighteenth century the chief method for acquiring knowledge of land was by surveying and mapping it. -

Proceedings of the Historical Society of Queensland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Queensland eSpace Proceedings of the Historical Society of Queensland. At a meeting of the Committee of the Historical Society of Queensland held in October, 1922, certain proposals were made for the celebration of the Hundredth Anni versary of the Discovery of the Brisbane River on 2nd December, 1823. These were communicated to the Bris bane City Council and embodied in the programme eventuaUy carried out. The Society undertook to prepare a manuscript of the field books or journals of Mr. John Oxley, Surveyor General of New South Wales, on the occasions of the discovery of the river, and of his second visit in September, 1824, when he discovered the site of the city. The official celebrations were subsequently postponed tiU August, 1924. The actual date of the hundredth aryiiversary, 2nd December, feU upon a Sunday in 1923. The Mayor of Brisbane, Alderman H. J. Diddams, C.M.G., a foundation member of the Society, invited a large number of pioneers and others, including the President and other representatives of the Society to Newstead, formerly the residence of Captain Wickham, R.N., at the mouth of Breakfast Creek, on the afternoon of Saturday, 1st December, 1923, in sight of the discoverer's first land ing place within the present city area. His ExceUency Sir Matthew Nathan, G.C.M.G., Governor of Queensland and Patron of the Society, read a message from His Majesty the King as follows :— " I desire to congratulate my loyal people of Queensland on the marveUous progress made since the discovery of the Brisbane River a century ago and to convey to them my most cordial wishes for their con tinued happiness and prosperity." Addresses were delivered by His ExceUency, the Premier (the Hon. -

Risky Journeys: the Development of Best Practice Adult Educational Programs to Indigenous People in Rural and Remote Communities

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Education - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2007 Risky Journeys: The Development of Best Practice Adult Educational Programs to Indigenous People in Rural and Remote Communities Roselyn M. Dixon University of Wollongong, [email protected] Sophie E. Constable University of Sydney Robert Dixon University of Sydney Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/edupapers Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Dixon, Roselyn M.; Constable, Sophie E.; and Dixon, Robert: Risky Journeys: The Development of Best Practice Adult Educational Programs to Indigenous People in Rural and Remote Communities 2007, 231-240. https://ro.uow.edu.au/edupapers/229 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Risky Journeys: The Development of Best Practice Adult Educational Programs to Indigenous People in Rural and Remote Communities Roselyn May Dixon, University of Wollongong, NSW, Australia Robert John Dixon, University of Sydney, NSW, Australia Sophie Constable, University of Sydney, NSW, Australia Abstract: The findings from a culturally relevant innovative educational program to support community health through dog health are presented. It will report on the pilot of a program, using a generative curriculum model where Indigenous knowledge is brought into the process of teaching and learning by community members and is integrated with an empirical knowledge base. The characteristics of the pilot program will be discussed. These included locally relevant content, appro- priate learning processes such as the development of personal caring relationships, and supporting different world views. -

3 the Later Maritime Prose

3 THE LATER MARITIME PROSE The scenery here exceeded any thing I had previously seen in Australia — extending for miles along a deep rich valley, clothed with magnificent trees, the beautiful uniformity of which was only interrupted by the turns and windings of the river, which here and there appeared like small lakes The philosophically intriguing qualities of maritime texts are clearest— however skeletally limned in—in our region's earlier exploratory prose or navigation studies and chronicles. Yet similar elements are still present in subsequent maritime texts, even in those constructed in seemingly a more familiar time and ordered navigational age. The unknown and unknowable and so dangerous element is most evident in the texts recording early landings—where white vulnerability and (mercantile) opportunism are both at that time peculiarly heightened. In the later works of the period, the initial undertone of danger becomes blended with the construction of a coastal zone with its own colonial or administrative demands and social patterns of duty. The maritime prose in this chapter has been chosen comprehensively, yet archival searches beyond the scope of this study are likely to yield more. Brief journeys, where one's interest and mindset clearly lie elsewhere, must position the passing region as but a conduit with minimal distinctive or savoured features. Yet even within such over-confident acceptance of the unfamiliar, with a life- style elsewhere, the unknown can. severely disrupt. Accidents experienced as well as the natural phenomena descried, can always emerge as fresh and exciting to fracture the stable construction. Minor difficulties are suppressed in the texts—resulting from the large number of practical journeys undertaken. -

67 SOME NOTES on COORPAROO. (By the Late Professor CUMBRAE STEWART)

67 SOME NOTES ON COORPAROO. (By the late Professor CUMBRAE STEWART). (Read by Mr. C. G. Austin at a meeting of the Historical Society of Queensland, July 26, 1938). When the boat of the colonial cutter "Mermaid" passed up the Brisbane River on Tuesday, December 2nd, 1823, with John Oxley, Surveyor General, of New South Wales, and Lieutenant Stirling of "The Buffs," the mouth of a water course or tributary {o the river was noticed on the southern bank, and marked on the chart. This tributary, afterwards known as Norman Creek, received the waters falling on an area roughly shaped like a horseshoe, the watershed of which is a line of heights ending in Galloway's Hill on the east and on the west in Highgate Hill. On the western side the chief stream feeding the Norman were those which formed the "One Mile Swamp" now, in great part, carried by a tunnel into the river, and, further south, the waters of King fisher Creek. Norman Creek itself receives the waters flowing down from the southern watershed, of which the chief natural feature is Mount Gravatt. On its eastern bank, the Norman Creek is fed by Coorparoo and Bridgewater Creeks, which are water courses rather than permanently flowing streams until they reach salt water. The suburb now knowm as Coorparoo may be described as the ground drained by these twd creeks, swampy in the flats along the Norman, but, for the most part, high lying and well drained, open to the cool sea breezes from the north west, and affording an excellent panoramic view of the city. -

The Impact of Australia's Distinctive Nature and Ecology on Imperial

The impact of Australia’s distinctive nature and ecology on imperial expansion in the first years of settlement in New South Wales Lucinda Janson Australia’s nature and ecology have been shaped over millennia by geological and climatic factors into a distinctive and complex ecosystem. The continent’s Aboriginal peoples adapted to the challenges of a variable and often hostile climate and landscape, and developed a sophisticated means of living off the land. Yet the arrival of a fleet of British ships to what would become known as New South Wales permanently altered this balance. The land would eventually be shaped by these invaders into what Alfred Crosby called a ‘neo-Europe’.1 Australia’s European colonisers had a complex and ever-changing relationship with the Australian landscape. During the early years of settlement in New South Wales, Europeans struggled to establish and maintain an imperial colony in a strange land. Their reluctance to understand the Aborigines and their connection with the indigenous plants and animals initially had harmful consequences for the imperial project. 1 Alfred Crosby, Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 2. 9 MERICI — VOLUME 1, 2015 Overcoming this early resistance, the settlers soon began to adapt their farming practices and even their diet to the new environment. Yet the ‘foreign’ aspects of Australia’s nature and ecology caused many Europeans to react by imposing their own plants and animals in order to ‘improve’ the land. Moreover, while some colonists praised and admired the landscape, others used the image of the city replacing the bush to demonstrate that the Europeans’ imperial achievement had involved a rejection of Australia’s distinctive nature. -

Australian Photography and Transnationalism

Australian Photography and Transnationalism ANNE MAXWELL UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE Transnationalism is a theoretical concept which today is widely used to describe the relations that have formed, and continue to form, across state boundaries (Howard 3). Used initially by scholars in the early 2000s to refer to the flow of goods and scientific knowledge between nations that ‘has increased significantly in modern times beginning with trade and empires in 1500’ (Howard 4), it has in recent years come to include the category of culture, a development that has in turn sparked a flood of publications aimed at interrogating nationalist histories. Among the first of these publications in Australia was Ann Curthoys and Marilyn Lake’s ground-breaking work Connected Worlds (2005), which radically transformed our conception of Australia’s past by repositioning Australian history ‘on the outer rim of Pacific and Indian Ocean studies, as a nodal point in British imperial studies and connected, or cast in a comparative light, with other settler colonial nations’ (Simmonds, Rees and Clark 1). Less than two years later in 2007, David Carter invoked what has come to be called the ‘transnational turn’ when he challenged scholars of Australian literature to focus on ‘the circulation of cultures beneath and beyond the level of the nation’ (Carter 114–19). His call, like that of Curthoys and Lake, was in response to several decades of scholarship emphasising the cultural nationalism which as Robert Dixon, in his compelling study of the photographic and cinematographic works of Frank Hurley observes, ‘began in the 1960s’ and ‘peak[ed] probably in the decade from 1977 to 1987’ (Dixon xxv). -

Glenburn Precinct (Blocks 16, 30, 60, 71–73, and 94, Kowen)

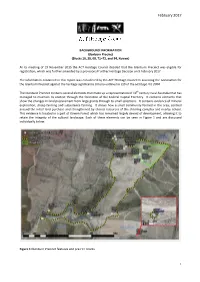

February 2017 BACKGROUND INFORMATION Glenburn Precinct (Blocks 16, 30, 60, 71–73, and 94, Kowen) At its meeting of 19 November 2015 the ACT Heritage Council decided that the Glenburn Precinct was eligible for registration, which was further amended by a provisional Further Heritage Decision on 9 February 2017. The information contained in this report was considered by the ACT Heritage Council in assessing the nomination for the Glenburn Precinct against the heritage significance criteria outlined in s10 of the Heritage Act 2004. The Glenburn Precinct contains several elements that make up a representation of 19th century rural Australia that has managed to maintain its context through the formation of the Federal Capital Territory. It contains elements that show the changes in land procurement from large grants through to small selections. It contains evidence of mineral exploration, sheep farming and subsistence farming. It shows how a small community formed in the area, centred around the initial land purchase and strengthened by shared resources of the shearing complex and nearby school. This evidence is located in a part of Kowen Forest which has remained largely devoid of development, allowing it to retain the integrity of the cultural landscape. Each of these elements can be seen in Figure 1 and are discussed individually below. Figure 1 Glenburn Precinct features and pre-FCT blocks 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION – GLENBURN PRECINCT – NOVEMBER 2015 General background CULTURAL LANDSCAPES The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) defines organically evolved cultural landscapes as those that have resulted ‘from an initial social, economic, administrative, and/or religious imperative and has developed its present form by association with and in response to its natural environment. -

Early Commandants of Moreton

385 EARLY COMMANDANTS OF MORETON BAY [By LOUIS CRANFIELD] (Read before a meeting of the Society on 24 October 1963.) The Moreton Bay Convict Settlement was one of five prin cipal convict stations in early AustraUa, the others being located at Port Macquarie, N.S.W., Macquarie Harbour and Port Arthur in Tasmania, and Norfolk Island. The Moreton Bay station was established following an enquiry conducted by John Thomas Bigge, who visited New South Wales between the years 1819 and 1821. The purpose of the enquiry was to investigate the possibility of abolishing the transportation system. The visit, however, appears to have had the opposite effect, for the 1820's are recognized as the worst years in the convict era. Bigge estimated the cost of buUding the settlement at Moreton Bay to be £4,150, and the annual cost of main taining it to be £27,500. Lt. Henry MiUer was appointed first Commandant and he arrived at Redcliffe, in company with the Surveyor-General, John Oxley, on 14 September 1824. He had charge of approximately 50 soldiers and convicts. UNSUITABLE LOCALITY The locality proved completely unsuited for the station and it was transferred to the present site of Brisbane in November of that year. The reason for the selection of the unsatisfactory site was probably due to Miller's observing the official instructions too closely. The instructions, which were dated 27 August 1824, are as follows: "To provide security and subsistence for the runaways from Port Macquarie." The Commandant was to be guided by the judgment of the Surveyor-General in the selection of the location, which was preferably to be an airy situation, close to fresh water, and not a moment to be lost in the construction of huts for soldiers and convicts. -

353 the Changing Face of Brisbane

353 THE CHANGING FACE OF BRISBANE [By MR. E. D. MELLOR, Acting Surveyor-General.] (Read November 26, 1959.) To illustrate this paper, I arranged that two maps be prepared on a scale of one chain to an inch; one of these maps shows Brisbane as it was at the time of the survey by Robert Dixon in 1840; the other, plotted on a transparent medium, shows the existing alignment of North Quay and William Street area. 1. St. John's; 2. Commandant's House (afterwards Colonial Secretary's Office); 3. Evangelical Church; 4. Capt. Feez' residence; 5. Devonshire House, George St.; 6. Dowse's Wharf; 7. Ship Inn; 8. Queen's Wharf; 9. Commissariat Stores; 10. Ferry to Russell St., Sth. Brisbane. the city streets. By superimposing the latter on the base map the changes which have taken place in the original alignments may be clearly seen; the changes were effected principally in the period when civil juris diction followed the closing of the convict era in 1839.^ Unfortunately, it is impracticable to reproduce these two maps in this publication; however, a copy of part of Robert Dixon's 1840 survey plan is reproduced on page —. It should be noticed that no street names appear on 1.—In 1839 surveyors were sent to Moreton Bay to lay out sites for towns and villages. These were Robert Dixon, James Warner, Stapylton, Tuck and Dunlop. Stapylton and Tuck were murdered by aboriginals near Mt. Lindsay in 1840. Dixon was recalled to Sydney in August 1841 and replaced by Henry Wade. Dixon com mitted the unforgivable crime of publicly commenting on the improper conduct of the then Commandant Gorman. -

Ginninderra Catchment Area Historical Notes

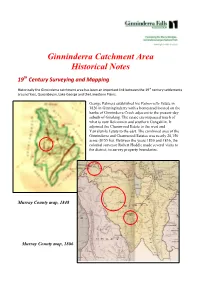

Ginninderra Catchment Area Historical Notes 19th Century Surveying and Mapping Historically the Ginninderra catchment area has been an important link between the 19th century settlements around Yass, Queanbeyan, Lake George and the Limestone Plains. George Palmers established his Palmerville Estate in 1826 in Ginninginderry with a homestead located on the banks of Ginninderra Creek adjacent to the present-day suburb of Giralang. The estate encompassed much of what is now Belconnen and southern Gungahlin. It adjoined the Charnwood Estate to the west and Yarralumla Estate to the east. The combined area of the Ginninderra and Charnwood Estates was nearly 20,150 acres (8155 ha). Between the years 1830 and 1836, the colonial surveyor Robert Hoddle made several visits to the district, to survey property boundaries. Murray County map, 1848 Murray County map, 1886 Robert Hoddle sketch of Ginninderra Falls, 1835. Robert Hoddle map, 1835 The area now known as to us as Gungahlin was originally called after the major waterway, Ginninderra Creek, which begins at Oak Hill, just over the NSW border, and flows west into the Murrumbidgee through Ginninderra Falls. Ginin-ginin-derry is said to mean ‘sparkling, throwing out little rays of light’ in the local Ngunnawal language, and is possibly a description of the waterfall (Cooke, 2010). Robert Hoddle map 1832 (National Library of Australia) Robert Dixon map, published in 1837 Robert Dixon surveyed area in 1828 to sort out unofficial occupation of properties. After Dixon’s survey the district was open to authorised permanent occupation. One Tree Hill Oak Hill Surveyors Hall Hill Charnwood Percival Hill Parkwood Goodwin Palmerville Hill Ginninderra Creek catchment area In 1824 the “King’s Botanist” Allan Cunningham arrived in the district and on 19 April visited the area around Ginninderra and recorded valuable sheep pastures and a large river winding to the north-northeast (presumably the Murrumbidgee River). -

Journal 3: 2012

BLUEHISTORY MOUNTAINS JOURNAL Blue Mountains Association of Cultural Heritage Organisations Issue 3 October 2012 I Blue Mountains History Journal 3: 2012 THE BLUE MOUNTAINS: WHERE ARE THEY? Andy Macqueen PO Box 204 Wentworth Falls NSW 2782 [email protected] Abstract When the name ‘Blue Mountains’ was first applied in New South Wales in 1789 it referred to the extensive ranges that were visible from, and bounded, the colony. It was widely considered in the nineteenth century that the Blue Mountains extended from the Goulburn area in the south to the Hunter Valley in the north. Today the name is applied in various ways, but usually in a very local sense. This evolution reflects the cultural history of the region. Today’s official definition validates the evolved narrative that Blaxland, Wentworth and Lawson completely crossed the Blue Mountains in 1813. Key Words: Blue Mountains, definition, Greater, National Park, maps, explorers. Introduction If people standing at Echo Point or Mount Tomah are asked where they think the Blue Mountains extend to in the landscape before them, a very diverse response is obtained. Few people today have a clear idea of the coverage of the Blue Mountains (Figure 1), and that has been the case since the colony began. It is not a trivial question. For over two centuries the name ‘Blue Mountains’ has been entwined with the story of the region, and indeed of New South Wales. But if the name has had different meanings at different times or in different contexts, it is necessary to understand those meanings if history is to be properly interpreted.