Sources and Problems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

07 July 1980, No 3

AUSTRALIANA SOCIETY NEWSLETTER 1980/3 July 1980 •• • • • •• • •••: •.:• THE AUSTRALIANA SOCIETY NEWSLETTER ISSN 0156.8019 The Australiana Society P.O. Box A 378 Sydney South NSW 2000 1980/3, July 1980 SOCIETY INFORMATION p. k NOTES AND NEWS P-5 EXHIBITIONS P.7 ARTICLES - John Wade: James Cunningham, Sydney Woodcarver p.10 James Broadbent: The Mint and Hyde Park Barracks P.15 Kevin Fahy: Who was Australia's First Silversmith p.20 Ian Rumsey: A Guide to the Later Works of William Kerr and J. M. Wendt p.22 John Wade: Birds in a Basket p.24 NEW BOOKS P.25 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS p.14 OUR CONTRIBUTORS p.28 MEMBERSHIP FORM P.30 Registered for posting as a publication - category B Copyright C 1980 The Australiana Society. All material written or illustrative, credited to an author, is copyright. pfwdaction - aJLbmvt Kzmkaw (02) 816 U46 it Society information NEXT MEETING The next meeting of the Society will be at the Kirribilli Neighbourhood Centre, 16 Fitzroy Street, Kirribilli, at 7-30 pm on Thursday, 7th August, 1980. This will be the Annual General Meeting of the Society when all positions will be declared vacant and new office bearers elected. The positions are President, two Vice-Presidents, Secretary, Treasurer, Editor, and two Committee Members. Nominations will be accepted on the night. The Annual General Meeting will be followed by an AUCTION SALE. All vendors are asked to get there early to ensure that items can be catalogued and be available for inspection by all present. Refreshments will be available at a moderate cost. -

San Martín: Argentine Patriot, American Liberator

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON INSTITUTE OF LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES OCCASIONAL PAPERS No. 25 San Martín: Argentine Patriot, American Liberator John Lynch SAN MARTíN: ARGENTINE PATRIOT, AMERICAN LIBERATOR John Lynch Institute of Latin American Studies 31 Tavistock Square London WC1H 9HA The Institute of Latin American Studies publishes as Occasional Papers selected seminar and conference papers and public lectures delivered at the Institute or by scholars associated with the work of the Institute. John Lynch is Emeritus Professor of Latin American History in the University of London, where he has spent most of his academic career, first at University College, then from 1974 to 1987 as Director of the Institute of Latin American Studies. The main focus of his work has been Spanish America in the period 1750–1850. Occasional Papers, New Series 1992– ISSN 0953 6825 © Institute of Latin American Studies University of London, 2001 San Martín: Argentine Patriot, American Liberator 1 José de San Martín, one of the founding fathers of Latin America, comparable in his military and political achievements with Simón Bolívar, and arguably incomparable as a model of disinterested leadership, is known to history as the hombre necesario of the American revolution. There are those, it is true, who question the importance of his career and reject the cult of the hero. For them the meaning of liberation is to be found in the study of economic struc- tures, social classes and the international conjuncture, not in military actions and the lives of liberators. In this view Carlyle’s discourse on heroes is a mu- seum piece and his elevation of heroes as the prime subject of history a misconception. -

Winter 2012 SL

–Magazine for members Winter 2012 SL Olympic memories Transit of Venus Mysterious Audubon Wallis album Message Passages Permanence, immutability, authority tend to go with the ontents imposing buildings and rich collections of the State Library of NSW and its international peers, the world’s great Winter 2012 libraries, archives and museums. But that apparent stasis masks the voyages we host. 6 NEWS 26 PROVENANCE In those voyages, each visitor, each student, each scholar Elegance in exile Rare birds finds islets of information and builds archipelagos of Classic line-up 30 A LIVING COLLECTION understanding. Those discoveries are illustrated in this Reading hour issue with Paul Brunton on the transit of Venus, Richard Paul Brickhill’s Biography and Neville on the Wallis album, Tracy Bradford on our war of nerves business collections on Olympians such as Shane Gould and John 32 NEW ACQUISITIONS Konrads, and Daniel Parsa on Audubon’s Birds of America, Library takes on Vantage point one of our great treasures. Premier’s awards All are stories of passage, from Captain James Cook’s SL French connection Art of politics voyage of geographical and scientific discovery to Captain C THE MAGAZINE FOR STATE LIBRARY OF NSW BUILDING A STRONG ON THIS DAY 34 FOUNDATION MEMBERS, 8 James Wallis’s album that includes Joseph Lycett’s early MACQUARIE STREET FRIENDS AND VOLUNTEERS FOUNDATION Newcastle and Sydney watercolours. This artefact, which SYDNEY NSW 2000 IS PUBLISHED QUARTERLY 10 FEATURE New online story had found its way to a personal collection in Canada, BY THE LIBRARY COUNCIL PHONE (02) 9273 1414 OF NSW. -

Correcting Misconceptions About the Names Applied to Tasmania’S Giant Freshwater Crayfish Astacopsis Gouldi (Decapoda: Parastacidae)

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 152, 2018 21 CORRECTING MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT THE NAMES APPLIED TO TASMANIA’S GIANT FRESHWATER CRAYFISH ASTACOPSIS GOULDI (DECAPODA: PARASTACIDAE) by Terrence D. Mulhern (with three plates) Mulhern, T.D. 2018 (14:xii) Correcting misconceptions about the names applied to Tasmania’s Giant Freshwater Crayfsh Astacopsis gouldi (Decapoda:Parastacidae). Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 152: 21–26. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.152.21 ISSN 0080–4703. Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, School of Biomedical Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Vic 3010, Australia. Email: [email protected] Tasmania is home to around 35 species of freshwater crayfsh, all but three of which are endemic. Among the endemic freshwater crayfsh, there are three large stream-dwelling species: the Giant Freshwater Crayfsh, Astacopsis gouldi – the world’s largest freshwater invertebrate, the medium-sized A. tricornis and smaller A. franklinii. Errors and confusion surrounding the appropriate Aboriginal names for these species, and the origin and history of the scientifc name of Astacopsis gouldi are outlined. Key Words: Tasmanian freshwater crayfsh, giant freshwater lobster, Giant Freshwater Crayfsh, Astacopsis gouldi Aboriginal words, lutaralipina, tayatitja, scientifc names, William Buelow Gould, Charles Gould. INTRODUCTION tribe in the far south. Plomley also lists a further two variants from Joseph Milligan’s later vocabulary: ‘tayatea’ (Oyster Bay) Tasmania is home to three species of large stream-dwelling and ‘tay-a-teh’ (Bruny Island/South) (Milligan 1859). It is freshwater crayfsh assigned to the endemic genus Astacopsis. important to note that these were English transliterations of Of these three species, Astacopsis gouldi Clark, 1936, known Aboriginal words, as heard by the recorders, none of whom commonly as the Giant Freshwater Crayfsh, or ‘lobster’, is were trained linguists, and interpretation of the signifcance the world’s largest freshwater invertebrate. -

Phanfare Jan/Feb 2009

Newsletter of the Professional Historians’ Association (NSW) No. 234 January – February 2009 PHANFARE Phanfare is the newsletter of the Professional Historians Association (NSW) Inc Published six times a year Annual subscription: Free download from www.phansw.org.au Hardcopy: $38.50 Articles, reviews, commentaries, letters and notices are welcome. Copy should be th received by 6 of the first month of each issue (or telephone for late copy) Please email copy or supply on disk with hard copy attached. Contact Phanfare GPO Box 2437 Sydney 2001 Enquiries Annette Salt, [email protected] Phanfare 2008‐09 is produced by the following editorial collectives: Jan‐Feb & July‐Aug: Roslyn Burge, Mark Dunn, Shirley Fitzgerald, Lisa Murray Mar‐Apr & Sept‐Oct: Rosemary Broomham, Rosemary Kerr, Christa Ludlow, Terri McCormack May‐June & Nov‐Dec: Ruth Banfield, Cathy Dunn, Terry Kass, Katherine Knight, Carol Liston, Karen Schamberger Disclaimer Except for official announcements the Professional Historians Association (NSW) Inc accepts no responsibility for expressions of opinion contained in this publication. The views expressed in articles, commentaries and letters are the personal views and opinions of the authors. Copyright of this publication: PHA (NSW) Inc Copyright of articles and commentaries: the respective authors ISSN 0816‐3774 2 Phanfare no.334 Jan – Feb 2009 PHANFARE No.234 January – February 2009 Contents: President’s Page Virginia Macleod 4 Report ‐ History Council of NSW Mark Dunn 5 Article – Altruism and digital archives Peter Hobbins 6 Book Notes Peter Tyler 8 Review – Bondi Jitterbug Mark Dunn 11 Review – Old Registers DVD Terry Kass 13 Report – PHA visit to the National Archives Janette Pelosi 16 What’s On Christine de Matos 22 Cover image: This beauty contest was uncovered by Mark Dunn while diligently researching at the Mitchell Library photographic possibilities for the interpretation of Tallawarra Power Station. -

Roads Thematic History

Roads and Maritime Services Roads Thematic History THIS PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK ROADS AND TRAFFIC AUTHORITY HERITAGE AND CONSERVATION REGISTER Thematic History Second Edition, 2006 RTA Heritage and Conservation Register – Thematic History – Second Edition 2006 ____________________________________________________________________________________ ROADS AND TRAFFIC AUTHORITY HERITAGE AND CONSERVATION REGISTER Thematic History Second Edition, 2006 Compiled for the Roads and Traffic Authority as the basis for its Heritage and Conservation (Section 170) Register Terry Kass Historian and Heritage Consultant 32 Jellicoe Street Lidcombe NSW, 2141 (02) 9749 4128 February 2006 ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2 RTA Heritage and Conservation Register – Thematic History – Second Edition 2006 ____________________________________________________________________________________ Cover illustration: Peak hour at Newcastle in 1945. Workers cycling to work join the main Maitland Road at the corner of Ferndale Street. Source: GPO1, ML, 36269 ____________________________________________________________________________________ 3 RTA Heritage and Conservation Register – Thematic History – Second Edition 2006 ____________________________________________________________________________________ Abbreviations DMR Department of Main Roads, 1932-89 DMT Department of Motor Transport, 1952-89 GPO1 Government Printer Photo Collection 1, Mitchell Library MRB Main Roads Board, 1925-32 SRNSW State Records of New South -

E-Book Code: REAU1036

E-book Code: REAU1036 Written by Margaret Etherton. Illustrated by Terry Allen. Published by Ready-Ed Publications (2007) © Ready-Ed Publications - 2007. P.O. Box 276 Greenwood Perth W.A. 6024 Email: [email protected] Website: www.readyed.com.au COPYRIGHT NOTICE Permission is granted for the purchaser to photocopy sufficient copies for non-commercial educational purposes. However, this permission is not transferable and applies only to the purchasing individual or institution. ISBN 1 86397 710 4 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012 12345678901234 5 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 -

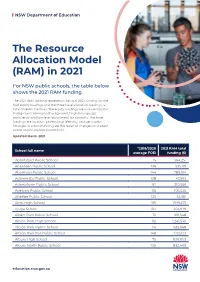

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

Francis Barrallier, Explorer, Surveyor, Engineer, Artillery Officer, Aide-De-Camp, Architect and Ship Designer: Three Years in New South Wales (1800-1803)

FRANCIS BARRALLIER, EXPLORER, SURVEYOR, ENGINEER, ARTILLERY OFFICER, AIDE-DE-CAMP, ARCHITECT AND SHIP DESIGNER: THREE YEARS IN NEW SOUTH WALES (1800-1803) VALERIE LHUEDE' Ensign Barrallier [... discharged] the duties of Military Engineer and Artillery Officer, superintending the Military Defences, Batteries and Cannon of this Settlement, in addition to which he has most arduously and voluntarily executed the duties of Civil Engineer and Surveyor to the advancement of the Geography and the Natural History of the Territory.2 I have informed you [Sir Joseph Banks] in my several letters of the great use Ensign Barrallier, of the NSW Corps, was of to me and the public, first in going to the southward and surveying the coast from Wilson's Promontory to Western Port; next in surveying Hun ter's River, where he went twice; and since then in making journey to the mountains, which was introductory to his undertaking the journey he afterwards performed. [...] As Col. Paterson has thought proper [...] to write me officially that Mr. Barrallier's excursions were contrary to the Duke of York's instructions, I found myself obliged to give him up, and relinquish this highly desirable object for the present. I [was] concerned at it, as the young man has such ardour and perseverance that I judged much public benefit would have resulted to his credit and my satisfaction. [...] In conse quence, I [...] claimed him as my aide-de-camp, and mat the object of discovery should not be totally relinquished, I sent him on an embassy to the King of the Mountains. Governor Philip Gidley King3 Chris Cunningham, in his book Blue Mountains Rediscovered* quotes Mark Twain in Following the Equator (1831) as saying, "Australian history is full of surprises, and adventures, and incongruities, and contradictions and incredibilities, but they are all true, they all happened". -

Sydney Australia Inquests 1826.Pdf

New South Wales Inquests, 1819; 10 June 2008 1 SYD1819 SYDNEY GAZETTE, 10/04/1819 Court of Criminal Jurisdiction Wylde J.A., 7 April 1819 This was a day of serious trial for the murder of WILLIAM COSGROVE , a settlor and district constable upon the Banks of the South Creek, on the first of the present month; by the discharge of the contents of a musket loaded with slugs into his body, of which wounds he died the following day. The prisoners were TIMOTHY BUCKLEY by whom the gun was fired; DAVID BROWN , and TIMOTHY FORD , all of whom had been in the Colony but six of seven months, and prisoners in the immediate employee of Government, and who unhappily had not renounced those propensities which sooner or later were to lead them to an unhappy end. The first witness called was THOMAS COSGROVE , brother of the deceased, whose testimony was conclusive of the fact. The witness stated, that his murdered brother was a district constable at the South Creek; and that he having seen, and believing the three prisoners at the bar to be bushrangers, requested him, the witness, to joining in pursuit of the suspected persons; all of which was readily compiled with, and a pursuit accordingly commenced. This was about one in the afternoon; the deceased went up to the three men (the prisoners at the bar), and found then in conversation with two young men who were brothers of the name of York, one of them a son in law of the deceased. The deceased called to the prisoners at the bar, declaring his willingness to point them out the road to the place they were enquiring for, namely the "Five mile Farm;" but appearing conscious that they were armed bushrangers, he hesitated not to rescue their giving themselves up to him, he being a district constable. -

Ecology of Pyrmont Peninsula 1788 - 2008

Transformations: Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula 1788 - 2008 John Broadbent Transformations: Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula 1788 - 2008 John Broadbent Sydney, 2010. Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula iii Executive summary City Council’s ‘Sustainable Sydney 2030’ initiative ‘is a vision for the sustainable development of the City for the next 20 years and beyond’. It has a largely anthropocentric basis, that is ‘viewing and interpreting everything in terms of human experience and values’(Macquarie Dictionary, 2005). The perspective taken here is that Council’s initiative, vital though it is, should be underpinned by an ecocentric ethic to succeed. This latter was defined by Aldo Leopold in 1949, 60 years ago, as ‘a philosophy that recognizes[sic] that the ecosphere, rather than any individual organism[notably humans] is the source and support of all life and as such advises a holistic and eco-centric approach to government, industry, and individual’(http://dictionary.babylon.com). Some relevant considerations are set out in Part 1: General Introduction. In this report, Pyrmont peninsula - that is the communities of Pyrmont and Ultimo – is considered as a microcosm of the City of Sydney, indeed of urban areas globally. An extensive series of early views of the peninsula are presented to help the reader better visualise this place as it was early in European settlement (Part 2: Early views of Pyrmont peninsula). The physical geography of Pyrmont peninsula has been transformed since European settlement, and Part 3: Physical geography of Pyrmont peninsula describes the geology, soils, topography, shoreline and drainage as they would most likely have appeared to the first Europeans to set foot there. -

The Handbook of World Englishes

The Handbook of World Englishes THOA01 1 19/07/2006, 11:33 AM Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics This outstanding multi-volume series covers all the major subdisciplines within lin- guistics today and, when complete, will offer a comprehensive survey of linguistics as a whole. Already published: The Handbook of Child Language The Handbook of Language and Gender Edited by Paul Fletcher and Brian Edited by Janet Holmes and MacWhinney Miriam Meyerhoff The Handbook of Phonological Theory The Handbook of Second Language Edited by John A. Goldsmith Acquisition Edited by Catherine J. Doughty and The Handbook of Contemporary Semantic Michael H. Long Theory Edited by Shalom Lappin The Handbook of Bilingualism Edited by Tej K. Bhatia and The Handbook of Sociolinguistics William C. Ritchie Edited by Florian Coulmas The Handbook of Pragmatics The Handbook of Phonetic Sciences Edited by Laurence R. Horn and Edited by William J. Hardcastle and Gregory Ward John Laver The Handbook of Applied Linguistics The Handbook of Morphology Edited by Alan Davies and Edited by Andrew Spencer and Catherine Elder Arnold Zwicky The Handbook of Speech Perception The Handbook of Japanese Linguistics Edited by David B. Pisoni and Edited by Natsuko Tsujimura Robert E. Remez The Handbook of Linguistics The Blackwell Companion to Syntax, Edited by Mark Aronoff and Janie Volumes I–V Rees-Miller Edited by Martin Everaert and The Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Henk van Riemsdijk Theory The Handbook of the History of English Edited by Mark Baltin and Chris Collins Edited by Ans van Kemenade and The Handbook of Discourse Analysis Bettelou Los Edited by Deborah Schiffrin, Deborah The Handbook of English Linguistics Tannen, and Heidi E.