Good Film, Bad Jury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

X********X************************************************** * Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made * from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 302 264 IR 052 601 AUTHOR Buckingham, Betty Jo, Ed. TITLE Iowa and Some Iowans. A Bibliography for Schools and Libraries. Third Edition. INSTITUTION Iowa State Dept. of Education, Des Moines. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 312p.; Fcr a supplement to the second edition, see ED 227 842. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibllographies; *Authors; Books; Directories; Elementary Secondary Education; Fiction; History Instruction; Learning Resources Centers; *Local Color Writing; *Local History; Media Specialists; Nonfiction; School Libraries; *State History; United States History; United States Literature IDENTIFIERS *Iowa ABSTRACT Prepared primarily by the Iowa State Department of Education, this annotated bibliography of materials by Iowans or about Iowans is a revised tAird edition of the original 1969 publication. It both combines and expands the scope of the two major sections of previous editions, i.e., Iowan listory and literature, and out-of-print materials are included if judged to be of sufficient interest. Nonfiction materials are listed by Dewey subject classification and fiction in alphabetical order by author/artist. Biographies and autobiographies are entered under the subject of the work or in the 920s. Each entry includes the author(s), title, bibliographic information, interest and reading levels, cataloging information, and an annotation. Author, title, and subject indexes are provided, as well as a list of the people indicated in the bibliography who were born or have resided in Iowa or who were or are considered to be Iowan authors, musicians, artists, or other Iowan creators. Directories of periodicals and annuals, selected sources of Iowa government documents of general interest, and publishers and producers are also provided. -

Past Blackfriars' Theatre Productions

PAST BLACKFRIARS' THEATRE PRODUCTIONS PRODUCTION DATE DIRECTOR Les Miserables: School Edition 2020 Spring Edward Lawrence Clue On Stage 2019 Fall Edward Lawrence Mamma Mia! 2019 Spring Edward Lawrence A Christmas Carol 2018 Fall Edward Lawrence Jesus Christ Superstar 2018 Spring Edward Lawrence Peter and the Starcatcher 2017 Fall Edward Lawrence You're A Good Man, Charlie Brown 2017 Spring Edward Lawrence It's A Wonderful Life 2016 Fall Edward Lawrence Godspell 2016 Spring Edward Lawrence And Then There Were None 2015 Fall Edward Lawrence The Addams Family 2015 Spring Edward Lawrence Uh Oh! Here Comes Christmas 2014 Fall Edward Lawrence Curtains 2014 Spring Edward Lawrence All I Need To Know I Learned in Kindergarten 2013 Fall Edward Lawrence How to Succeed in Business 2013 Spring Edward Lawrence Anything Goes (Alumni Show) 2012 Fall Edward Lawrence Hello Dolly! 2012 Spring Edward Lawrence Our Town 2011 Fall Edward Lawrence Oklahoma 2011 Spring Edward Lawrence Memories and Dreams (Alumni Show) 2010 Fall Edward Lawrence Joseph and Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat 2010 Spring Edward Lawrence M*A*S*H 2009 Fall Edward Lawrence Fiddler on the Roof 2009 Spring Edward Lawrence The Mousetrap 2008 Fall Edward Lawrence Beauty and the Beast 2008 Spring Edward Lawrence No Time For Sergeants 2007 Fall Edward Lawrence High School Musical 2007 Spring Edward Lawrence The Caine Mutiny Court Martial 2006 Fall Edward Lawrence Footloose 2006 Spring Edward Lawrence The Odd Couple 2005 Fall Edward Lawrence Bye Bye Birdie 2005 Spring Edward Lawrence Amadeus 2004 -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

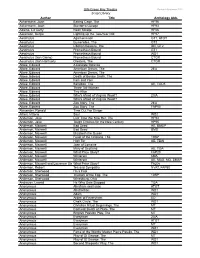

UW-Green Bay Theatre Script Library

UW-Green Bay Theatre Revised: November 2012 Script Library Author Title Anthology Abb. Ackermann, Joan Batting Cage, The HF96 Ackermann, Joan Stanton's Garage HF93 Adams, Liz Duffy Neon Mirage HF06 Aerenson, Benjie Lighting up the Two-Year Old HF97 Aeschylus Agamenmnon GT1, ATOT Aeschylus Eumenides, The GT3 Aeschylus Libation Bearers, The DD, GT2 Aeschylus Prometheus Bound GT1 Aeschylus Prometheus Bound WD1 Aeschylus (tran Grene) Prometheus Bound CTGR Aeschylus (tran Harrison) Oresteia, The CTGR Albee, Edward A Delicate Balance Albee, Edward American Dream, The 2EA Albee, Edward American Dream, The Albee, Edward Death of Bessie Smith, The Albee, Edward Fam and Yam Albee, Edward Sandbox, The AE, TOD5 Albee, Edward Three Tall Women Albee, Edward Tiny Alice Albee, Edward Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? 23IA Albee, Edward Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Albee, Edward Zoo Story, The 2EA Albee, Edward Zoo Story, The FAP50 Alexander, Ronald Time Out For Ginger Alfieri, Vittorio Saul WD2 Anderson, Jane Last Time We Saw Her, The HF94 Anderson, Jane Tough Choices for the New Century HF95 Anderson, Maxwell Bad Seed AE, BMSP Anderson, Maxwell Bad Seed BMS Anderson, Maxwell Elizabeth the Queen Anderson, Maxwell Feast of the Ortolans, The 10SP Anderson, Maxwell High Tor AE, TDAI Anderson, Maxwell Joan of Lorraine Anderson, Maxwell Mary of Scotland AE, TGA Anderson, Maxwell What Price Glory? FAP20 Anderson, Maxwell Winterset 6MA Anderson, Maxwell Winterset AE, MAD, MD, SMAP Anderson, Maxwell and Laurence StallingsWhat Price Glory? FA20s Anderson, Robert -

A History of Production

A HISTORY OF PRODUCTION 2020-2021 2019-2020 2018-2019 Annie Stripped: Cry It Out, Ohio State The Humans 12 Angry Jurors Murders, The Empty Space Private Lies Avenue Q The Wolves The Good Person of Setzuan john proctor is the villain As It Is in Heaven Sweet Charity A Celebration of Women’s Voices in Musical Theatre 2017-2018 2016-2017 2015-2016 The Cradle Will Rock The Foreigner Reefer Madness Sense and Sensibility Upton Abbey Tartuffe The Women of Lockerbie A Piece of my Heart Expecting Isabel 9 to 5 Urinetown Hello, Dolly! 2014-2015 2013-2014 2012-2013 Working The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later The Miss Firecracker Contest Our Town The 25th Annual Putnam County The Drowsy Chaperone Machinal Spelling Bee Anna in the Tropics Guys and Dolls The Clean House She Stoops to Conquer The Lost Comedies of William Shakespeare 2011-2012 2010-2011 2009-2010 The Sweetest Swing in Baseball Biloxi Blues Antigone Little Shop of Horrors Grease Cabaret Picasso at the Lapin Agile Letters to Sala How I Learned to Drive Love’s Labour’s Lost It’s All Greek to Me Playhouse Creatures 2008-2009 2007-2008 2006-2007 Doubt Equus The Mousetrap They’re Playing Our Song Gypsy Annie Get Your Gun A Midsummer Night’s Dream The Importance of Being Earnest Rumors I Hate Hamlet Murder We Wrote Henry V 2005-2006 2004-2005 2003-2004 Starting Here, Starting Now Oscar and Felix Noises Off Pack of Lies Extremities 2 X Albee: “The Sandbox” and “The Zoo All My Sons Twelfth Night Story” Lend Me a Tenor A Day in Hollywood/A Night in the The Triumph of Love Ukraine Babes in Arms -

Scripts and Set Plans for the Television Series the Defenders, 1962-1965 PASC.0129

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1b69q2wz No online items Scripts and Set Plans for the Television Series The Defenders, 1962-1965 PASC.0129 Finding aid prepared by UCLA staff, 2004 UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2020 November 2 Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Scripts and Set Plans for the PASC.0129 1 Television Series The Defenders, 1962-1965 PASC.0129 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: The Defenders scripts and set plans Identifier/Call Number: PASC.0129 Physical Description: 3 Linear Feet(7 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1962-1965 Abstract: The Defenders was televised 1961 to 1965. The series featured E.G. Marshall and Robert Reed as a father-son team of defense attorneys. The program established a model for social-issue type television series that were created in the early sixties. The collection consists of annotated scripts from January 1962 to March 1965. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

"Twelve Angry Men" by Reginald Rose. Dear Parents and Families

News for Union College parents and families. Students perform in "Twelve," a play based on "Twelve Angry Men" by Reginald Rose. Dear Parents and Families: A MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN OF STUDENTS Winter term has been busier than ever, featuring scores of events, from guest lectures, art exhibits and a student theater production of “Twelve” to celebrations of culture, gender and race. Guest lecturer David Clarke spoke about the intersection between religious studies and politics. Students discussed perceptions of time with the Philosophy Club and shared their words at the International Poetry Fest. In addition, a group of students hosted a week of inspiring events to raise awareness of human trafficking, featuring guest speakers from the FBI and Safe Inc., and Corbin Addison, author of A Walk Across the Sun. The College hosted a dozen events commemorating February as Black History Month. During Hijabi for a Day, the campus community learned about the Islamic tradition of Hijab. In addition, the entire campus is busy with Recyclemania, an eight-week recycling competition that pits Union against 400 other schools in the U.S. and Canada. And for the fourth straight year, our students took part in Random Acts of Kindness Week, planned by the Kenney Community Center, with activities and community service on- and off-campus. This has become a welcome Union tradition, turning the coldest month on the calendar into one of the warmest on campus. Please read further for other news from campus. Stephen C. Leavitt Vice President for Student Affairs and Dean of Students NEWS FROM CAMPUS Founders Day Laura Skandera Trombley, a nationally recognized champion of liberal arts education, will deliver the keynote address at Founders Day on Thursday, Feb. -

This Month on Tcm Showcases

WEEKLY THIS MONTH ON TCM SHOWCASES 1 BILLY WILDER COMEDIES 8 AN EVENING IN THE 12TH 15 MAY FLOWERS 22 STARRING CEDRIC HARDWICKE Sergeant York (’41) THE ESSENTIALS CENTURY Stalag 17 (’53) A Foreign Affair (’48) The Blue Dahlia (’46) The Hunchback of Notre Dame (’39) Must-See Classics The Great Escape (’63) Some Like It Hot (’59) The Lion in Winter (’68) Days of Wine and Roses (’62) Nicholas Nickelby (’47) Saturdays at 8:00pm (ET) The Bridge on the River Kwai (’57) The Fortune Cookie (’66) The Adventures of Robin Hood (’38) Please Don’t Eat the Daisies (’60) On Borrowed Time (’39) 5:00pm (PT) King Rat (’65) The Major and the Minor (’42) Robin and Marian (’76) What’s Up, Tiger Lily? (’66) King Solomon’s Mines (’37) A Foreign Affair (’48) Billy Wilder Speaks (’06) Becket (’64) Brother Orchid (’40) The Desert Fox (’51) 29 MEMORIAL DAY WEEKEND WAR The Lion in Winter (’68) The Blue Gardenia (’53) Valley of the Sun (’42) MOVIE MARATHON The Blue Dahlia (’46) 2 GOVERNESSES NOT NAMED MARIA 9 MOTHER’S DAY FEATURES The Hunchback of Notre Dame (’39) You’re in the Army Now (’41) Dragonwyck (’46) So Big (’53) 16 STARRING EDDIE BRACKEN 23 WE GOT YOUR GOAT The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) Buck Privates (’41) All This, and Heaven Too (’40) Gypsy (’62) Hail the Conquering Hero (’44) A Kid for Two Farthings (’56) In Harm’s Way (’65) About Face (’52) The Rising of the Moon (’57) 3 ROBERT OSBORNE’S PICKS 10 GUEST PROGRAMMER: Battle of the Bulge (’65) TCM UNDERGROUND Cult Classics Can’t Help Singing (’44) SHIRLEY JONES 17 STARRING ROSSANO BRAZZI 24 BASED ON -

William Powell ~ 23 Films

William Powell ~ 23 Films William Horatio Powell was born 29 July 1892 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In 1907, he moved with his family to Kansas City, Missouri, where he graduated from Central High School in 1910. The Powells lived just a few blocks away from the Carpenters, whose daughter Harlean also found success in Hollywood as Blonde Bombshell Jean Harlow, although she and Powell did not meet until both were established actors. After school, Powell attended New York City's American Academy Of Dramatic Arts. Work in vaudeville, stock companies and on Broadway followed until, in 1922, aged 30, playing an evil henchman of Professor Moriarty in a production of Sherlock Holmes, his Hollywood career began. More small parts followed and he did sufficiently well that, in 1924, he was signed by Paramount Pictures, where he stayed for the next seven years. Though stardom was elusive, he did eventually attract attention as arrogant film director Lev Andreyev in The Last Command (1928) before finally landing his breakthrough role, that of detective Philo Vance in The Canary Murder Case (1929). Unlike many silent actors, the advent of sound boosted Powell's career. His fine, urbane voice, stage training and comic timing greatly aided his successful transition to the talkies. However, not happy with the type of roles he was getting at Paramount, in 1931 he switched to Warner Bros. His last film for them, The Kennel Murder Case (1933), was also his fourth and last Philo Vance outing. In 1934 he moved again, to MGM, where he was paired with Myrna Loy in Manhattan Melodrama (1934). -

Theater (THE) Courses 1

Theater (THE) Courses 1 THE-106 Stagecraft THEATER (THE) COURSES This course introduces students to the fundamental concepts and practices of play production. Students develop a deeper awareness of THE-101 Introduction to Theater technical production and acquire the vocabulary and skills needed to This course explores many aspects of the theater: the audience, the actor, implement scenic design. These skills involve the proper use of tools the visual elements, the role of the director, theater history, and selected and equipment common to the stage, basic theatre drafting, scene dramatic literature. The goal is to heighten the student's appreciation painting, and prop building. Students will demonstrate skills in written and understanding of the art of the theater. The plays we will encounter and visual communication required to produce theater in a collaborative will range from the Greek tragedies of 2,500 years ago to new works environment. by contemporary playwrights: from Sophocles' Antigone to Lin-Manuel Prerequisites: none Miranda's Hamilton. Students will see and write reviews of theater Credit: 1 productions, both on- and off-campus. This course is appropriate for all Distribution: Literature/Fine Arts students, at all levels. THE-187 Independent Study Prerequisites: none Individual research projects. The manner of study will be determined by Credit: 1 the student in consultation with the instructor. Students must receive Distribution: Literature/Fine Arts written approval of their project proposal from a department Chair before THE-103 Seminars in Theater registering for the course. These seminars focus on specific topics in theater and film. They Prerequisites: none are designed to introduce students to the liberal arts expressed by Credits: 0.5-1 noteworthy pioneers and practitioners in theater and film. -

Elizabeth A. Schor Collection, 1909-1995, Undated

Archives & Special Collections UA1983.25, UA1995.20 Elizabeth A. Schor Collection Dates: 1909-1995, Undated Creator: Schor, Elizabeth Extent: 15 linear feet Level of description: Folder Processor & date: Matthew Norgard, June 2017 Administration Information Restrictions: None Copyright: Consult archivist for information Citation: Loyola University Chicago. Archives & Special Collections. Elizabeth A. Schor Collection, 1909-1995, Undated. Box #, Folder #. Provenance: The collection was donated by Elizabeth A. Schor in 1983 and 1995. Separations: None See Also: Melville Steinfels, Martin J. Svaglic, PhD, papers, Carrigan Collection, McEnany collection, Autograph Collection, Kunis Collection, Stagebill Collection, Geary Collection, Anderson Collection, Biographical Sketch Elizabeth A. Schor was a staff member at the Cudahy Library at Loyola University Chicago before retiring. Scope and Content The Elizabeth A. Schor Collection consists of 15 linear feet spanning the years 1909- 1995 and includes playbills, catalogues, newspapers, pamphlets, and an advertisement for a ticket office, art shows, and films. Playbills are from theatres from around the world but the majority of the collection comes from Chicago and New York. Other playbills are from Venice, London, Mexico City and Canada. Languages found in the collection include English, Spanish, and Italian. Series are arranged alphabetically by city and venue. The performances are then arranged within the venues chronologically and finally alphabetically if a venue hosted multiple productions within a given year. Series Series 1: Chicago and Illinois 1909-1995, Undated. Boxes 1-13 This series contains playbills and a theatre guide from musicals, plays and symphony performances from Chicago and other cities in Illinois. Cities include Evanston, Peoria, Lake Forest, Arlington Heights, and Lincolnshire. -

Johnson Received Two Boards

THREE WED THURS FRI MOSTLY SUNNY SUNNY PARTLY CLOUDY DAY 81% HUMIDITY 71% HUMIDITY 74% HUMIDITY FORECAST 80° | 56° 88° | 71° 90° | 64° THE $1 Vol. 132, No. 38 Holstein, IA 712-364-3131 www.holsteinadvance.com Wednesday, September 20, 2017 G-H, S-C voters elect board members Galva-Holstein and (34 from Galva, 79 from Hol- Schaller-Crestland voters stein and six from absentee went to the polls Sept. 12 to ballots). vote on seven seats on the Curtis Johnson received two boards. 353 yes votes from BC-IG and At Galva-Holstein, Jamie 107 votes from G-H for his Whitmer (District 1), David District 2 Western Iowa Tech Kistenmacher (District 3), Community College board Matthew Wittrock (District seat. 4) and Don Kalin (District 6) At S-C, incumbent Alan were elected. A total of 133, Movall defeated Gary Kron Jr., or 7.28 percent of G-H’s 1,828 175 (107 Schaller, 19 Nema- voters went to the polls, ac- ha, 48 Early, one absentee) to cording to unoficial results. 36 (28 Schaller, two Nemaha Incumbents Whitmer and and six Early) for the Dis- Kistenmacher received 116 trict 1 seat. Incumbent Tim 1122 AAngryngry WWomen:omen: (38 Galva, 78 Holstein and DeLance received 200 votes ADVANCE PHOTO | MIKE THORNHILL ive absentee) and 128 votes (124 Schaller, 21, Nemaha, 54 The Holstein Community Theatre performed “12 Angry Women” Sept. 16 and 17 at the Rosemary Clausen Center for (40 Galva, 82 Holstein and six Early and one absentee) and Performing Arts in Holstein. “12 Angry Women” is a drama based on the Emmy Award winning movie by Reginald Rose, absentee), respectively.