Arming Community Vigilantes in the Niger Delta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr. Modupe Oshikoya, Department of Political Science, Virginia Wesleyan University – Written Evidence (ZAF0056)

Dr. Modupe Oshikoya, Department of Political Science, Virginia Wesleyan University – Written evidence (ZAF0056) 1. What are the major security challenges facing Nigeria, and how effectively is the Nigerian government addressing them? 1.1 Boko Haram The insurgency group known globally as Boko Haram continues to wreak havoc in northeast Nigeria and the countries bordering Lake Chad – Cameroon, Chad and Niger. The sect refers to itself as Jamā'at Ahl as- Sunnah lid-Da'wah wa'l-Jihād [JAS], which in Arabic means ‘People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teaching and Jihad’, and rejects all Western beliefs. Their doctrine embraced the strict adherence to Islam through the establishment of sharia law across all of Nigeria, by directly attacking government and military targets.1 However, under their new leader, Abubakar Shekau, the group transformed in 2009 into a more radical Salafist Islamist group. They increased the number of violent and brutal incursions onto the civilian population, mosques, churches, and hospitals, using suicide bombers and improvised explosive devices (IEDs). The most prominent attack occurred in a suicide car bomb at the UN headquarters in Abuja in August 2011.2 Through the use of guerrilla tactics, Boko Haram’s quest for a caliphate led them to capture swathes of territory in the northeast of the country in 2014, where they indiscriminately killed men, women and children. One of the worst massacres occurred in Borno state in the town of Baga, where nearly an estimated 2,000 people were killed in a few hours.3 This radicalized ideological rhetoric of the group was underscored by their pledge allegiance to Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS) in March 2015, leading them rename themselves as Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWAP).4 One of the most troubling characteristics of the insurgency has been the resultant sexual violence and exploitation of the civilian population. -

Ikwerre Intergroup Relations and Its Impact on Their Culture

83 AFRREV VOL. 11 (2), S/NO 46, APRIL, 2017 AN INTERNATIONAL MULTI-DISCIPLINARY JOURNAL, ETHIOPIA AFRREV VOL. 11 (2), SERIAL NO. 46, APRIL, 2017: 83-98 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v11i2.7 Ikwerre Intergroup Relations and its Impact on Their Culture Chinda, C. Izeoma Department of Foundation Studies Port Harcourt Polytechnic, Rumuola Phone No: +234 703 667 4797 E-mail: [email protected] --------------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract This paper examined the intergroup relations between the Ikwerre of the Niger Delta, South-South geopolitical zone of Nigeria and its impact on their culture. It analyzed the Ikwerre relations with her Kalabari and Okrika coastal neighbours, as well as the Etche, Eleme, Ekpeye, Ogba Abua and the Igbo of Imo state hinterland neighbours. The paper concluded that the internal developments which were stimulated by their contacts impacted significantly on their culture. Key words: Ikwerre, Intergroup Relations, Developments, Culture, Neighbour. Introduction Geographical factors aided the movement of people from one ecological zone to another in migration or interdependent relationships of trade exchange. These exchanges and contacts occurred even in pre-colonial times. The historical roots of inter-group relations of the Ikwerre with her neighbours, dates back to pre-colonial times but became prevalent from the 1850 onward when the Atlantic trade became emphatic on agrarian products as raw materials to the industrial western world. This galvanized the hitherto existing inter-group contact between the Ikwerre and her neighbouring potentates. Copyright © International Association of African Researchers and Reviewers, 2006-2017: www.afrrevjo.net. -

An Assessment of the Socio-Economic Effects of Land Use Trends and Population Growth in Eleme, Rivers State, Nigeria

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 11, Issue 9, September-2020 1737 ISSN 2229-5518 An Assessment of the Socio-economic Effects of Land Use Trends and Population Growth in Eleme, Rivers State, Nigeria Obenade Moses, Ugochi E. Ekwugha, Ogungbemi A. Akinleye, Kanu C. Collins and Henry U. Okeke Abstract – Population growth in Eleme has been rapid over the past 82 years with its attendant pressure on the natural resources of the area. Between 1937 and 2006 the population of Eleme grew from 2,528 to 190,194 and is projected to be above 293,741 in 2019 based on an annual growth rate of 3.4 percent. Using the combined technologies of Geographic Information Systems (GIS), remote sensing (RS) and Demography techniques as its methodology, this paper examines the socio-economic effects of land use trends and population growth in Eleme between 1986 and 2019. The result of this study indicates that human population represents a threat to biodiversity in several ways. Thus if our patterns of consumption remain at the present rate, with more people, we will need to harvest more timber, catch more fish, plow more land for agriculture, dig up more fossil fuels and minerals, build more houses, and use more water. All of these demands impact wild species and increase the levels of pollution. Unless we find ways to dramatically increase crop yield per unit area, it will take much more land than is currently domesticated to feed people in the area if our population continue to grow at the prevailing rate of 3.4 percent annually. -

A Study of Demale Circumcision in Eastern Nigeria: Its Medical Signieicance

A STUDY OF DEMALE CIRCUMCISION IN EASTERN NIGERIA: ITS MEDICAL SIGNIEICANCE INTRODUCTION Nigeria is today the largest Colony and Protectorate under the Union Jack since India gained her independence. It will he re-called that Lagos, today the Federal Capital of Nigeria was created a British Colony in 1862. In January 1900, after cancellation of the Royal Niger Company1s Charter, the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria came into being. In the same year, the territory formerly known as the Niger Coast Protectorate was re named Southern Nigeria Protectorate. In 1906, the Colony of Lagos and its protected territory were amalgamated with the Protectorate of Southern Nigeria under one administration, with Lagos as the seat of the Government. In 1914, by Letters Patent and Order in Council, the Colony and Protectorate of Southern Nigeria and the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria were amalgamated and designated the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria, with Sir Frederick (later Lord) Lugard as the Governor-General. Various constitutional changes have taken place since Lord Lugard1s days. The latest Constitution, the 1. ProQuest Number: 13838901 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13838901 Published by ProQuest LLC(2019). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Ethnic Militias and Conflict in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria: the International Dimensions (1999-2009)

ETHNIC MILITIAS AND CONFLICT IN THE NIGER DELTA REGION OF NIGERIA: THE INTERNATIONAL DIMENSIONS (1999-2009) By Lysias Dodd Gilbert A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Political Science at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR ADEKUNLE AMUWO 2010 DECLARATION Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Graduate Programme in Political Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. I declare that this dissertation is my own unaided work. All citations, references and borrowed ideas have been duly acknowledged. I confirm that an external editor was not used. It is being submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities, Development and Social Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. None of the present work has been submitted previously for any degree or examination in any other University. ______________________________________ Lysias Dodd Gilbert ______________________________________ Date ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page...................................................................................................................................i Certification...............................................................................................................................ii Table of Contents.....................................................................................................................iii Dedication................................................................................................................................vii -

Political Violence and Terrorism

Florya Chronicles of Political Economy - Year 2 Number 2 - 2016 (123-145) Mining Eng. x x x x x x x x x x x x Political Violence and Terrorism: Insight Nano- technol ogy x Into Niger Delta Militancy and Boko Haram Nuclea r Energy x x Pharm 1 aceut x x x Özüm Sezin UZUN 2 Textile x x x x X Yusuf Saheed ADEGBOYEGA Touris m x x x x X x x x x x x x x X x x x Abstract Source: Adapted by the author from the National Development and The aim of this article is to examine the nexus between the following: Growth Strategy Plans of respective African countries. 1) the political violence and terrorism practiced by Niger Delta militants and Boko Haram insurgents in Nigeria, and 2) the governance of Nigeria. The article focuses on the historical trend of political violence since the amalgamation of the country and the impacts of terrorism. Before Nigerian independence, the country was organized by colonial powers under a protectorate system of both Northern and Southern regions, with people of different tribes and cultures living under different patterns of administrative governance. In 1914, colonial powers amalgamated the regions into one state, aiming for an easier administrative system. After amalgamation, a movement for self- governance emerged among the peoples of the newly united regions, though the only thing that both protectorates shared peacefully was the name of the country: Nigeria. The subsequent struggle for ethnic supremacy and the incidence of regional disparity, among other factors, 1 PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science and International Relations, Istanbul Aydın University. -

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Proponent Indorama Eleme Fertilizer And

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Proponent Indorama Eleme Fertilizer and Chemicals Limited (IEFCL) is a company organized and existing under the laws of Nigeria, with its registered office at Indorama Petrochemicals Complex, Eleme, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria. IEFCL manufactures 2300 MTPD Ammonia & 4000 MTPD Urea Fertilizer (IEFCL-Train 1) at its Eleme manufacturing complex. IEFCL is undertaking the development of IEFCL-Train2 fertilizer project to increase the production of Urea adjacent to the IEFCL-Train 1 within the existing manufacturing Indorama complex at Eleme. Need for the EIA This project has been categorized as category one project by the Federal Ministry of Environment (FMENV), who confirmed the need to conduct a full blown EIA. Terms of reference (TOR) The Terms of Reference for this Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) study include the following: Determination of the baseline environmental profile in and around the proposed project site. Rendering a qualitative and quantitative description of the physical, chemical, biological and social environments relevant to the project. Documentation of significant signposts, including the identification of potential impact and risks of the project on the surrounding environment at large. Recommendations and implementation of strategies to eliminate or reduce identified adverse impacts and risks Production of an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report with effective Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) EIA Objectives The objectives of the EIA are: Assessment of the state of the environment Establishment of environmental issues and factors associated with the proposed fertilizer project. Assessment and forecast of all possible and potential impacts of the proposed project on components of the environment in terms of magnitude and importance. -

Cranfield University Chigozie Emmanuel Amadi School of Applied Sciences the Niger Delta: Aspects of Human Health Risk Associate

CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY CHIGOZIE EMMANUEL AMADI SCHOOL OF APPLIED SCIENCES THE NIGER DELTA: ASPECTS OF HUMAN HEALTH RISK ASSOCIATED WITH THE PETROLEUM INDUSTRY M.Phil Academic Year: 2010- 2014 Supervisor: DR TERRY P. BROWN November, 2014 CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF APPLIED SCIENCES Toxicology, Health and Environment M.Phil Academic Year 2010-2014 CHIGOZIE EMMANUEL AMADI The Niger Delta: Aspects of Human Health Risk Associated with the Petroleum Industry Supervisor: Terry P. Brown November 2014 © Cranfield University 2014. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the copyright owner. ABSTRACT The Niger Delta has been described as one of the most petroleum-polluted places in the world. The oil and gas industry located in this region is the economic mainstay of Nigeria and has contributed to key aspects of life in our modern society. However, the indigenous nationalities and residents of the Niger Delta have been exposed to appalling environmental conditions due to the operations of the upstream petroleum industry within their communities. Whereas much is known about the environmental consequences of the operations of the oil and gas industries, including the fallout of crude oil spillage incidences, comparatively, very little is known about the risks to human health due to exposures to these environmental conditions. This could be a source of fear and frustration. The knowledge about the human health repercussions of the upstream petroleum industry operations in the Niger Delta is nonexistent. This study investigated some aspects of risk to human health in the Niger Delta due to the operations of the petroleum industry, especially carcinogenic risk. -

Election Results Transmitted to Server, INEC Ad-Hoc Officers Tell Tribunal

Mele Kyari: NNPC will Raise Bar on Transparency Promises to fix nation’s refineries by 2023 To unveil new roadmap in couple of weeks Kasim Sumaina in Abuja Corporation (NNPC) with Kyari, who promised to He spoke in Abuja at a join me to unveil the NNPC short and long term growth a pledge to continuously make the nation’s refineries valedictory ceremony for his Roadmap towards global objectives of the corporation as Mallam Mele Kyari assumed entrench transparency, functional by 2023, said in a predecessor, Dr. Maikanti Baru. excellence and the roadmap we transit to a national energy duty yesterday as the Group accountability and performance few weeks he would unveil Kyari said: “In the next will guide our aspirations to champion.” Managing Director of the excellence across all the oil his agenda for the nation’s couple of weeks, the COOs achieve sustained outstanding Nigerian National Petroleum corporation’s operations. oil sector. (chief operating officers) will performance to meet the Continued on page 8 Osinbajo: Ethno-Religious Suspicion Nigeria’s Greatest Problem... Page 6 Tuesday 9 July, 2019 Vol 24. No 8856. Price: N250 www.thisdaylive.com T RU N TH & REASO EIGHTY HEART CHEERS... L-R: Chief Bisi Akande, Ambassador Babagana Kingibe, Dr. Obafemi Hamzat, Governor Abdullahi Ganduje, a guest, Governor Dapo Abiodun, Senate President Ahmed Lawan, Vice President Yemi Osinbajo, Oba Rilwan Akiolu, another guest, Mrs Derinola Osoba, Chief Olusegun Osoba, a guest and Senator Bola Tinubu, during the presentation of Osoba’s book: Battlelines: Adventures into Journalism and Politics, to mark his 80th birthday in Lagos...yesterday KOLA OLASUPO Election Results Transmitted to Server, INEC Ad-hoc Officers Tell Tribunal Atiku, PDP call witnesses, tender more documents Alex Enumah in Abuja Two of the six witnesses called by the petitioners said Some witnesses in the hearing they served as ad-hoc staff of of the petition filed by the INEC and testified that results Peoples Democratic Party were transmitted electronically (PDP) and its presidential to the commission’s server. -

Directory of Development Organizations

EDITION 2010 VOLUME I.B / AFRICA DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2010, Volume I: Africa The directory of development organizations, listing 63.350 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance, -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

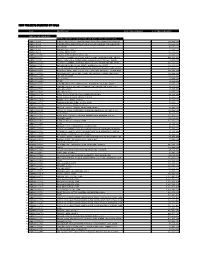

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

Nigeria's Niger Delta

Africa Development, Vol. XXXIV, No. 2, 2009, pp. 103–128 © Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, 2009 (ISSN 0850-3907) Nigeria’s Niger Delta: Understanding the Complex Drivers of Violent Oil-related Conflict Cyril Obi* Abstract This paper explores the complex roots and dimensions of the Niger Delta conflict which has escalated from ethnic minority protests against the federal Nigerian State-Oil Multinationals’ alliance in the 1990’s to the current insurgency that has attracted worldwide attention. It also raises some conceptual issues drawn from ‘snapshots’ taken from various perspectives in grappling with the complex roots of the oil- related conflict in the paradoxically oil-rich but impoverished region as an important step in a nuanced reading of the local, national and international ramifications of the conflict and its implications for Nigeria’s development. The conflict is then located both in the struggle of ethnic minority groups for local autonomy and the control of their natural resources (including oil), and the contradictions spawned by the transnational production of oil in the region. The transition from resistance – as-protest – to insurgency, as represented by attacks on state and oil company targets by the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND), is also critically analyzed. Résumé Cet article explore les racines et les dimensions complexes du conflit dans le delta du Niger qui a évolué à partir des protestations de la minorité ethnique contre l’alliance entre l’État fédéral nigérian et des multinationales pétrolières dans les années 1990, pour aboutir à l’actuelle insurrection qui a attiré l’attention du monde entier.