Explorations Into the Yoga-Dance Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rooted Elements a Kinesthetic Approach Connecting Our Children to Their Nnei R and Outer World Alisha Meyer the University of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Graduate School Professional Papers 2012 Rooted Elements A Kinesthetic Approach Connecting Our Children to Their nneI r and Outer World Alisha Meyer The University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Recommended Citation Meyer, Alisha, "Rooted Elements A Kinesthetic Approach Connecting Our Children to Their nneI r and Outer World" (2012). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1385. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1385 This Professional Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROOTED ELEMENTS A KINESTHETIC APPROACH CONNECTING OUR CHILDREN TO THEIR INNER AND OUTER WORLD By ALISHA BRIANNE MEYER BA Elementary Education, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, 2003 Professional Paper presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Fine Arts, Integrated Arts and Education The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2012 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Associate Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Karen Kaufmann, Chair Fine Arts Jillian Campana, Committee Member Fine Arts Rick Hughes, Committee Member Fine Arts © COPYRIGHT by Alisha Brianne Meyer 2012 All Rights Reserved ii Meyer, Alisha, M.A., May 2012 Integrating Arts into Education Rooted Elements Chairperson: Karen Kaufmann Rooted Elements is a thematic naturalistic guide for classroom teachers to design engaging lessons focused in the earth elements. -

Omega's 2010 Being Yoga Conference Retreat Brings 25+ Top Teachers to the Hudson Valley

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Chrissa Pullicino August 4, 2010 Office: 845.266.4444, ext. 404 Omega’s 2010 Being Yoga Conference Retreat Brings 25+ Top Teachers to the Hudson Valley Senior Teachers Offer Classes to Preserve the Rich Tradition of Yoga RHINEBECK, NY –Today Omega Institute, one of the nation’s most trusted sources for yoga education, announced its annual Being Yoga Conference Retreat will be held on its Rhinebeck, New York campus, from August 20 through 22. The event offers an in-depth exploration of the many facets of yoga practice—from therapeutic to philosophical. “Since 1977, Omega has been a place where people from all walks of life come for lifelong learning, inspired living, and building community,” said Carla Goldstein, director of external affairs and the Women’s Institute at Omega. “During Being Yoga, beginner and experienced yoga practitioners gather in community to learn from leading teachers about the depth of this ancient tradition and the promising ways yoga can enhance their modern lifestyle,” concluded Goldstein. In addition to physical yoga practice, the Being Yoga Conference Retreat will offer classes on a wide range of topics, including health and wellness practices such as meditation, vegetarian cooking, and dance. Guests of Being Yoga will design their own schedule, choosing from more than 50 dynamic classes, to explore what it means to “live your yoga.” In addition to choosing classes, guests can spend time in quiet contemplation, make new friends during meals and community gatherings, relax with a session at the Omega Wellness Center, and explore the outdoors. The conference opens Friday evening August 20, at 7:30 p.m. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Choreographers and Yogis: Untwisting the Politics of Appropriation and Representation in U.S. Concert Dance A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Jennifer F Aubrecht September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Chairperson Dr. Anthea Kraut Dr. Amanda Lucia Copyright by Jennifer F Aubrecht 2017 The Dissertation of Jennifer F Aubrecht is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I extend my gratitude to many people and organizations for their support throughout this process. First of all, my thanks to my committee: Jacqueline Shea Murphy, Anthea Kraut, and Amanda Lucia. Without your guidance and support, this work would never have matured. I am also deeply indebted to the faculty of the Dance Department at UC Riverside, including Linda Tomko, Priya Srinivasan, Jens Richard Giersdorf, Wendy Rogers, Imani Kai Johnson, visiting professor Ann Carlson, Joel Smith, José Reynoso, Taisha Paggett, and Luis Lara Malvacías. Their teaching and research modeled for me what it means to be a scholar and human of rigorous integrity and generosity. I am also grateful to the professors at my undergraduate institution, who opened my eyes to the exciting world of critical dance studies: Ananya Chatterjea, Diyah Larasati, Carl Flink, Toni Pierce-Sands, Maija Brown, and rest of U of MN dance department, thank you. I thank the faculty (especially Susan Manning, Janice Ross, and Rebekah Kowal) and participants in the 2015 Mellon Summer Seminar Dance Studies in/and the Humanities, who helped me begin to feel at home in our academic community. -

Beingyogapressrelease

For Immediate Release Contact: Chrissa Pullicino October 29, 2007 Phone: 201.951.8767 Omega Institute to Host Being Yoga Conference in Florida More than 35 Top, National Yoga Instructors to Teach Participants How to “Live Your Yoga” RHINEBECK, NY – In what might be characterized as a surprise to some, yoga, which in Sanskrit means “union,” is considered one of the “fastest growing trends in the United States,” according to Google Trends, a search engine that compares the world’s interest in given topics by analyzing their popularity online, in the news, and geographically. That development is, according to an Omega spokesperson, “partially the result of the work we’ve been doing at Omega Institute for 30 years.” It’s also one of the reasons Omega is hosting a “Being Yoga” Conference in Florida this November, according to Carla Goldstein, Omega’s Director of External Affairs. The conference will be held from November 2-5, 2007, in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. “Here at Omega we’ve known for many years what others are discovering every day: that yoga holds tremendous potential for strengthening and healing us as individuals and society,” said Ms. Goldstein. “As more people practice yoga we grow the possibility to create a society with more compassion and less violence.” Guests of the conference, which is being held at the Harbor Beach Marriott Resort & Spa, will have the opportunity to immerse themselves in the study and practice of yoga in its many forms and to learn what it means to live yoga on and off the mat. While yoga is now available in many communities, education may be limited to the style and approach of a particular teacher, making it challenging for students to get comprehensive exposure to the richness of the tradition. -

Ashtanga Yoga As Taught by Shri K. Pattabhi Jois Copyright ©2000 by Larry Schultz

y Ashtanga Yoga as taught by Shri K. Pattabhi Jois y Shri K. Pattabhi Jois Do your practice and all is coming (Guruji) To my guru and my inspiration I dedicate this book. Larry Schultz San Francisco, Califórnia, 1999 Ashtanga Ashtanga Yoga as taught by shri k. pattabhi jois Copyright ©2000 By Larry Schultz All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reprinted without the written permission of the author. Published by Nauli Press San Francisco, CA Cover and graphic design: Maurício Wolff graphics by: Maurício Wolff & Karin Heuser Photos by: Ro Reitz, Camila Reitz Asanas: Pedro Kupfer, Karin Heuser, Larry Schultz y I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead. His faithful support and teachings helped make this manual possible. forward wenty years ago Ashtanga yoga was very much a fringe the past 5,000 years Ashtanga yoga has existed as an oral tradition, activity. Our small, dedicated group of students in so when beginning students asked for a practice guide we would TEncinitas, California were mostly young, hippie types hand them a piece of paper with stick figures of the first series with little money and few material possessions. We did have one postures. Larry gave Bob Weir such a sheet of paper a couple of precious thing – Ashtanga practice, which we all knew was very years ago, to which Bob responded, “You’ve got to be kidding. I powerful and deeply transformative. Practicing together created a need a manual.” unique and magical bond, a real sense of family. -

Destination Within Sacred Homework

Destination Within Sacred Homework You will have three assignments and an exam to finish in order to complete your 200 hour Certification. These are assigned with love, knowing they will enhance and enrich your yoga practice to the extent that you devote time and focus to them. I personally have completed projects of a similar nature and found them extremely beneficial and enriching in both my personal yoga practice and my teaching career. You will complete the following (a total of 53 hours of homework) for certification: Practice Teaching, recording, and taking your own classes 7x Reading Projects – 7 books and book reports Embodiment Project Anatomy DVD & Coloring Sheets Practice Homework Final Exam You should work on these in the intervening 6 months between our 2 modules. The exam will take place at home after both modules are completed. Budget your time wisely and get your work done as early as possible. The four months will pass quicker than you think. You may also take time after the 2 nd module to finish the homework. You will not receive your certificate until the homework is complete – it is part of the course curriculum. Practice Teaching You will need an audio recorder for this exercise. If you have a smartphone it’s possible you can use that. You will design seven different sequences. One will be Prana Flow Vinyasa, one will be Forrest yoga and the other five can be any format you choose. You will design the sequences. You will then teach the class and record yourself teaching it. This can be a regular class you are teaching to the public, a private class you teach to volunteers, or you can have a ghost class where you just speak into the audio recorder with no live students present. -

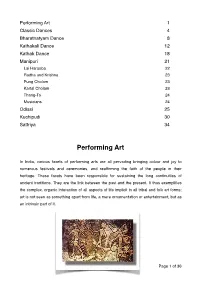

Classical Dances Have Drawn Sustenance

Performing Art 1 Classic Dances 4 Bharatnatyam Dance 8 Kathakali Dance 12 Kathak Dance 18 Manipuri 21 Lai Haraoba 22 Radha and Krishna 23 Pung Cholam 23 Kartal Cholam 23 Thang-Ta 24 Musicians 24 Odissi 25 Kuchipudi 30 Sattriya 34 Performing Art In India, various facets of performing arts are all pervading bringing colour and joy to numerous festivals and ceremonies, and reaffirming the faith of the people in their heritage. These facets have been responsible for sustaining the long continuities of ancient traditions. They are the link between the past and the present. It thus exemplifies the complex, organic interaction of all aspects of life implicit in all tribal and folk art forms; art is not seen as something apart from life, a mere ornamentation or entertainment, but as an intrinsic part of it. Page !1 of !36 Pre-historic Cave painting, Bhimbetka, Madhya Pradesh Under the patronage of Kings and rulers, skilled artisans and entertainers were encouraged to specialize and to refine their skills to greater levels of perfection and sophistication. Gradually, the classical forms of Art evolved for the glory of temple and palace, reaching their zenith around India around 2nd C.E. onwards and under the powerful Gupta empire, when canons of perfection were laid down in detailed treatise - the Natyashastra and the Kamasutra - which are still followed to this day. Through the ages, rival kings and nawabs vied with each other to attract the most renowned artists and performers to their courts. While the classical arts thus became distinct from their folk roots, they were never totally alienated from them, even today there continues a mutually enriching dialogue between tribal and folk forms on the one hand, and classical art on the other; the latter continues to be invigorated by fresh folk forms, while providing them with new thematic content in return. -

Bridging the Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances As a Source of Dance/Movement Therapy, a Literature Review

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses (GSASS) Spring 5-16-2020 Bridging The Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances as a source of Dance/Movement Therapy, A Literature Review. Ruta Pai Lesley University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses Part of the Art Education Commons, Counseling Commons, Counseling Psychology Commons, Dance Commons, Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pai, Ruta, "Bridging The Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances as a source of Dance/Movement Therapy, A Literature Review." (2020). Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses. 234. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses/234 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences (GSASS) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. BRIDGING THE GAP 1 Bridging the Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances as a source of Dance/Movement Therapy, A Literature Review. Capstone Thesis Lesley University August 5, 2019 Ruta Pai Dance/Movement Therapy Meg Chang, EdD, BC-DMT, LCAT BRIDGING THE GAP 2 ABSTRACT Indian Classical Dances are a mirror of the traditional culture in India and therefore the people in India find it easy to connect with them. These dances involve a combination of body movements, gestures and facial expressions to portray certain emotions and feelings. -

List of Hatha Yoga Postures, English and Sanskrit

Hatha Yoga Postures List English and Sanskrit Names Indexed by Type and Textbook Descriptions My Yoga and Chi Kung Class Exercises List By Michael P. Garofalo, M.S. Valley Spirit Yoga, Red Bluff, California Adho Downward Voc Adho Mukha Vrksasana Balancing on Hands, Handstand HBalP LoY287, YS361 Adho Mukha Svanasana Downward Facing Dog PP, Res, Mod3 Loy110, YtIY90, BSYB108, HYI30, AHY482, YA224, YS360 Agni Sara or Bidalasana Cat KP, BB BSYF128, HYI116, AHY193, YS376 Agni Sara Sunbird, Cat/Cow Variation KP BSYF132, AHY194 Agnistambhasana Fire Log, Two Footed King Pigeon SitP YS362 Ahimsa Not Harming, Non-Violence, Not Killing, Yama Voc Akarna Dhanurasana Shooting Bow Pose SitP YS362 Alanasana Lunge, Crescent Lunge StdP, BB BSYF166, HYI38 Alternate Nostril Breathing Nādī Shodhana Prānāyāma SitP LoY445-448, HYI16 Anantasana Side Leg Lift, Vishnu’s Serpent Couch LSP LoY246, YtIY87 Anjaneyasana Lunge, Low or High Lunge StdP, StdBalP YS364 Anji Stambhasana SitP Apanāsana Knees to Chest SupP BSYF182, HYI180 Aparigraha Noncovetousness, Not Greedy, Yama Voc Ardha Half, Partial, Modified Voc Ardha Baddha Padmottanasana Half Bound Lotus Intense Stretch Pose StdP, StdBalP YS365 Ardha Chandrasana Half Moon Balancing StdP, StdBalP LoY74, YtIY30, BSYF94, HYI74, YS366 Ardha Navasana Boat Modified SitP LoY111 Ardha Matsyendrasana I Lord of the Fishes Spinal Twist TwP, Mod4, SitP LoY259, YtIY74, BSYF154, HYI128-131, YS367 Ardha Padmasana Half Cross Legged Seated SitP YtIY54 Ardha Salabhasana Half Locust PP, BB, Mod4 LoY99, YtIY92, BSYF136, HYI110, AHY297, YA218 Ardha Uttanasana Half Forward Fold, Monkey StdP YS368 Asana Posture, Position, Pose Voc Ashta Chandrasana High Lunge, Crescent StdP, StdBalP YS368 Hatha Yoga and Chi Kung Class Postures List By Michael P. -

March 2020 Easy Pose with Prayer Hands Sukhasana-Namaste

Lord of the Dance Pose January 2020 Natarajasana 1 2 3 4 Happy New Year 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Martin Luther King Chinese New Year 26 27 28 29 30 31 NOTES: Inspired by America’s Warriors Model Name: N/A Standing Pigeon Pose February 2020 Tada Kapotasana 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Groundhog Day 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Valentine’s Day 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 . 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 NOTES: Original image by Robert Sturman Model Name: Angelo Carongcong Easy Pose with Prayer Hands March 2020 Sukhasana-Namaste 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mahashivaratri 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Daylight Savings 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 St. Patrick’s Day 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 NOTES: Original image by Robert Sturman Model Name: Michael Narvid Tree Pose with Prayer Hands April 2020 Vrksasana-Namaste 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Good Friday 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Easter 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Earth Day 26 27 28 29 30 NOTES: Original image by Robert Sturman Model: Susan Alden Side Plank Pose May 2020 Vasisthasana 1 2 Cinco de Mayo 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Mother’s Day 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Armed Forces Day 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Memorial Day NOTES: Inspired by America’s Warriors Model Name: N/A Easy Pose with Conscious Breathing Hands June 2020 Sukhasana – Conscious Breathing Hands 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Flag Day 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Father’s Day 28 29 30 NOTES: Original image by Robert Sturman Model Name: Rebecca Smith Mountain Pose with Prayer Hands July 2020 Tadasana - Namaste 1 2 3 4 Independence Day 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 -

Arm Balances and Inversions

Leverage and Power: Arm Balances and Inversions Essential Dynamics • Arm-balancing is empowering, inspiring, and, well, hard. In fact, the challenging nature of arm-balancing often leads students to overwork and rely on raw force instead of technique and focus. • The intensity of these postures can also lead to an attraction/aversion complex: Students will tend to be attracted to their striking beauty and either push, push, push to get there, or they’ll take a bathroom break and disconnect from their practice. • What often gets overlooked is that arm balances require you to relax deeply and release many of your joints and muscles. You need a lot of suppleness in your groins, hamstrings, hips, knees, and torso just to get into the shape of most of these poses; once you develop this, you won’t have to work so hard. • Many people struggle with these postures because they simply don’t understand how to do them—not necessarily because they’re not strong or flexible enough. • In order to learn these postures, most people need them broken down into small, accessible components. • Focus on preparatory poses that open your joints and get your body deeply familiar with the shape of each of the arm-balances. • Cultivate a playful, curious, and non-striving attitude. Notice if you become overly intense in your desire to perform the pose or, conversely, if you’re tempted to throw in the towel because they seem too challenging. If that happens, let go and search for the delicate balance between effort and relaxation. Use the exploration of these poses to practice meeting any challenge with understanding, acceptance, and resilience. -

Kathak Through the Ages, the Last Choreography of Guru Maya Rao in 2014, Video Projection in the Background Adds to the Dynamism of the Choreography

PAPER 4 Detail Study Of Kathak, Nautch Girls, Nritta, Nritya, Different Gharana-s, Present Status, Institutions, Artists Module 20 Modern Development And Future Trends In Kathak Kathak though an ancient dance form, with clear established history, has grown to a massive body of work, making it veer towards what is contemporary and modern. The words contemporary and modern are two different terms in context of art. Any art form, design, film, fashion, music can be contemporary. Each generation or time cycle brings something to the table of this development in society but modern means a whole new language. It means new structure, new grammar and new form. So, in dance when we speak of a modern Kathak, what does it imply? Kathak has certain grammar and structure, as with any and most dance forms. Thus, when we say modern Kathak, it doesn’t mean we break the grammar or change costume - that is just innovation or making it more in tune with contemporary desires of a society at any given point of time. 1 Many believe that Kumudhini Lakhia’s solo performance entitled Duvidha was a turning point of Kathak as a dance form. She founded the Kadamb School of Dance and Music in Ahmedabad in 1967 and has done more than 70 successful productions all over the world. Her choreographies include Dhabkar / धबकार, Yugal / युगऱ, Atah Kim / अथ: ककम, The Peg, Okha-Haran / ओखा हरण, Sama Samvadan / सम संवाद, Suverna / सुवण,ण Bhav Krida / भाव क्रीड़ा, Golden Chains, Kolaahal / कोऱाहऱ, Mushti / मुष्टि to name a few.