25 Kraitsowits Ac

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(C) 1978 by Random House, Inc. Introduction: "The Dean of Science

A Del Rey Book - Published by Ballantine Books Copyright (c) 1978 by Random House, Inc. Introduction: "The Dean of Science Fiction" Copyright (c) 1978 by J. J. Pierce All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Ballantine Books of Canada, Ltd., Toronto, Canada. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 78-52210 ISBN 0-345-25800-2 Manufactured in the United States of America First Edition: April 1978 Cover art by H. R. Van Dongen ACKNOWLEDGMENTS "Sidewise in Time," copyright (c) 1934 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Stories, June 1934. "Proxima Centauri," co~yright (c) 1935 by Street & Smith Pub.. lications, Inc., for Astounding Stories, March 1935. - "The Fourth-dimensional Demonstrator," copyright (c) 1935 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Stories, December 1935. "First Contact," copyright (c) 1945 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Science Fiction, May 1945. "The Ethical Equations," copyright (c) 1945 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Science Fiction, June 1945. "Pipeline to Pluto," copyright (c) 1945 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Science Fiction, August 1945. "The Power," copyright (c) 1945 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Science Fiction, September 1945. "A Logic Named Joe," copyright (c) 1946 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Science Fiction, March 1946. "Symbiosis," copyright (c) 1947 for Collier's Magazine, January 1947. "The Strange Case of John Kingman," copyright (c) 1948 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Science Fiction, May 1948. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

FANTASY NEWS TEN CENTS the Science Fiction Weekly Newspaper Volume 4, Number 21 Sunday, May 12

NEWS PRICE: WHILE THREE IT’S ISSUES HOT! FANTASY NEWS TEN CENTS the science fiction weekly newspaper Volume 4, Number 21 Sunday, May 12. 1940 Whole Number 99 FAMOUS FANTASTIC FACTS SOCIAL TO BE GIVEN BY QUEENS SFL THE TIME STREAM The next-to-last QSFL meeting which provided that the QSFL in Fantastic Novels, long awaited The Writer’s Yearbook for 1940 of the 39-40 season saw an attend vestigate the possibilities of such an companion magazine to Famous contains several items of consider ance of close to thirty authors and idea. The motion was passed by a Fantastic Mysteries, arrived on the able interest to the science fiction fans. Among those present were majority with Oshinsky. Hoguet. newsstands early this week. This fan. There is a good size picture of Malcolm Jameson, well know stf- and Unger on investigating com new magazine presents the answer Fred Pohl, editor of Super Science author; Julius Schwartz and Sam mittee. It was pointed out that if to hundreds of stfans who wanted and Astonishing, included in a long Moskowitz, literary agents special twenty fans could be induced to pay to read the famous classics of yester pictorial review of all Popular Pub izing in science fiction; James V. ten dollars apiece it would provide year and who did not like to wait lications; there is also, the informa Taurasi. William S. Sykora. Mario two hundred dollars which might months for them to appear in serial tion that Harl Vincent has had ma Racic, Jr., Robert G. Thompson, be adequate to rent a “science fiction terial in Detective Fiction Weekly form. -

To Sunday 31St August 2003

The World Science Fiction Society Minutes of the Business Meeting at Torcon 3 th Friday 29 to Sunday 31st August 2003 Introduction………………………………………………………………….… 3 Preliminary Business Meeting, Friday……………………………………… 4 Main Business Meeting, Saturday…………………………………………… 11 Main Business Meeting, Sunday……………………………………………… 16 Preliminary Business Meeting Agenda, Friday………………………………. 21 Report of the WSFS Nitpicking and Flyspecking Committee 27 FOLLE Report 33 LA con III Financial Report 48 LoneStarCon II Financial Report 50 BucConeer Financial Report 51 Chicon 2000 Financial Report 52 The Millennium Philcon Financial Report 53 ConJosé Financial Report 54 Torcon 3 Financial Report 59 Noreascon 4 Financial Report 62 Interaction Financial Report 63 WSFS Business Meeting Procedures 65 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Saturday…………………………………...... 69 Report of the Mark Protection Committee 73 ConAdian Financial Report 77 Aussiecon Three Financial Report 78 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Sunday………………………….................... 79 Time Travel Worldcon Report………………………………………………… 81 Response to the Time Travel Worldcon Report, from the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention…………………………… 82 WSFS Constitution, with amendments ratified at Torcon 3……...……………. 83 Standing Rules ……………………………………………………………….. 96 Proposed Agenda for Noreascon 4, including Business Passed On from Torcon 3…….……………………………………… 100 Site Selection Report………………………………………………………… 106 Attendance List ………………………………………………………………. 109 Resolutions and Rulings of Continuing Effect………………………………… 111 Mark Protection Committee Members………………………………………… 121 Introduction All three meetings were held in the Ontario Room of the Fairmont Royal York Hotel. The head table officers were: Chair: Kevin Standlee Deputy Chair / P.O: Donald Eastlake III Secretary: Pat McMurray Timekeeper: Clint Budd Tech Support: William J Keaton, Glenn Glazer [Secretary: The debates in these minutes are not word for word accurate, but every attempt has been made to represent the sense of the arguments made. -

Program Book

GREETINGS to The 2 1st WO RETD SCIENCE E I C T I O KT C CONVENTION Th.e 2 1st 'WOFiLTD SCIENCE FICTION C ONVENTION VPtz shinqton, <DC 31 August 1 September 1 q e 3 2 September 'y am Cammittee: CRAFTY CHAIRMAN .................................... George Scithers TACHYLEGIC TREASURER ....................................... Bill Evans DESPOTIC DIPLOMAT .......................................... Bob Pavlat EXTEMPORANIZING EDITOR .................................... Dick Eney FLAMBOYANT FOLIATOR .................................... Chick Derry RECRUDESCENT RELIC ....................................... Joe Sarno MEMORIALIST of MISDEEDS.................................... Bob Madle TARTAREAN TABULIST .................................... Bill Osten PUBLICISTEAN PHOTOGRAPHIST .............................. Tom Haughey _A.n Appreciation of Murray £ein$ter It was in the year 1919 or '20, when I was fifteen and every fine fantasy story I read was an electric experience, that I read "The Mad Planet". It was a terrific nightmare vision and instantly I added the name of Murray Leinster to the list that already held A. Merritt, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and a few others. I have been reading and admiring his stories ever since, and I hope they go on forever. Mr. Leinster is a professional, in the finest sense of the word, meaning that he has the skills of his profession at his fingertips. And his profession is that of a master story-teller. His stories take hold of you from the first page and build with a sheer craftmanship and econ omy of effort that are the envy and despair of anyone who has ever tried to do the same thing. In science-fiction, imagination is even more important than writ ing skill, and the boldness of his imaginative concepts is one big rea son why Murray Leinster’s name has been up there in the bright lights for so long. -

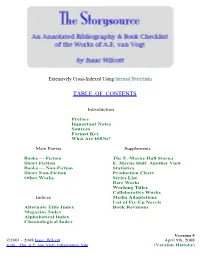

Table of Contents

Extensively Cross-Indexed Using Internal Hyperlinks TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Preface Important Notes Sources Format Key What Are ISBNs? Main Entries Supplements Books — Fiction The E. Mayne Hull Stories Short Fiction E. Mayne Hull: Another View Books — Non-Fiction Statistics Short Non-Fiction Production Chart Other Works Series List Rare Works Working Titles Collaborative Works Indices Media Adaptations List of Fix-Up Novels Alternate Title Index Book Revisions Magazine Index Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Version 5 ©2001 - 2008 Isaac Wilcott April 9th, 2008 Icshi: The A.E. van Vogt Information Site (Version History) Preface This new document, the Storysource, replaces both the Database and Compendium by combining the two. (I suppose you could call this a "fix-up" bibliography since it is the melding of previously "published" material into a new unified whole. And, in the true van Vogtian tradition, I've not only revised it but I've given it a new title as well.) The last versions of both are still available for download as a single ZIP file for those who would like them for whatever reason. The format of the Compendium has been retained with only a few alterations while adding the bibliographic information of the Database. A section for short stories has accordingly been added. The ugly and outdated Database is eliminated, while retaining all of its positive traits, and the usefulness of the Compendium is drastically improved. No longer will you have to jump between the two while looking something up — all information has been pooled into just one document. This new format's interface is more intuitive, alphabetically arranged rather than chronological, and with all items thoroughly cross- indexed with internal hyperlinks. -

For Fans by Fans: Early Science Fiction Fandom and the Fanzines

FOR FANS BY FANS: EARLY SCIENCE FICTION FANDOM AND THE FANZINES by Rachel Anne Johnson B.A., The University of West Florida, 2012 B.A., Auburn University, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Department of English and World Languages College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities The University of West Florida In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2015 © 2015 Rachel Anne Johnson The thesis of Rachel Anne Johnson is approved: ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Baulch, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Earle, Ph.D., Committee Chair Date Accepted for the Department/Division: ____________________________________________ _________________ Gregory Tomso, Ph.D., Chair Date Accepted for the University: ____________________________________________ _________________ Richard S. Podemski, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank Dr. David Earle for all of his help and guidance during this process. Without his feedback on countless revisions, this thesis would never have been possible. I would also like to thank Dr. David Baulch for his revisions and suggestions. His support helped keep the overwhelming process in perspective. Without the support of my family, I would never have been able to return to school. I thank you all for your unwavering assistance. Thank you for putting up with the stressful weeks when working near deadlines and thank you for understanding when delays -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction

Andrew May Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction Editorial Board Mark Alpert Philip Ball Gregory Benford Michael Brotherton Victor Callaghan Amnon H Eden Nick Kanas Geoffrey Landis Rudi Rucker Dirk Schulze-Makuch Ru€diger Vaas Ulrich Walter Stephen Webb Science and Fiction – A Springer Series This collection of entertaining and thought-provoking books will appeal equally to science buffs, scientists and science-fiction fans. It was born out of the recognition that scientific discovery and the creation of plausible fictional scenarios are often two sides of the same coin. Each relies on an understanding of the way the world works, coupled with the imaginative ability to invent new or alternative explanations—and even other worlds. Authored by practicing scientists as well as writers of hard science fiction, these books explore and exploit the borderlands between accepted science and its fictional counterpart. Uncovering mutual influences, promoting fruitful interaction, narrating and analyzing fictional scenarios, together they serve as a reaction vessel for inspired new ideas in science, technology, and beyond. Whether fiction, fact, or forever undecidable: the Springer Series “Science and Fiction” intends to go where no one has gone before! Its largely non-technical books take several different approaches. Journey with their authors as they • Indulge in science speculation—describing intriguing, plausible yet unproven ideas; • Exploit science fiction for educational purposes and as a means of promoting critical thinking; • Explore the interplay of science and science fiction—throughout the history of the genre and looking ahead; • Delve into related topics including, but not limited to: science as a creative process, the limits of science, interplay of literature and knowledge; • Tell fictional short stories built around well-defined scientific ideas, with a supplement summarizing the science underlying the plot. -

Eng 4936 Syllabus

ENG 4936 (Honors Seminar): Reading Science Fiction: The Pulps Professor Terry Harpold Spring 2019, Section 7449 Time: MWF, per. 5 (11:45 AM–12:35 PM) Location: Little Hall (LIT) 0117 office hours: M, 4–6 PM & by appt. (TUR 4105) email: [email protected] home page for Terry Harpold: http://users.clas.ufl.edu/tharpold/ e-Learning (Canvas) site for ENG 4936 (registered students only): http://elearning.ufl.edu Course description The “pulps” were illustrated fiction magazines published between the late 1890s and the late 1950s. Named for the inexpensive wood pulp paper on which they were printed, they varied widely as to genre, including aviation fiction, fantasy, horror and weird fiction, detective and crime fiction, railroad fiction, romance, science fiction, sports stories, war fiction, and western fiction. In the pulps’ heyday a bookshop or newsstand might offer dozens of different magazines on these subjects, often from the same publishers and featuring work by the same writers, with lurid, striking cover and interior art by the same artists. The magazines are, moreover, chock-full of period advertising targeted at an emerging readership, mostly – but not exclusively – male and subject to predictable The first issue of Amazing Stories, April 1926. Editor Hugo Gernsback worries and aspirations during the Depression and Pre- promises “a new sort of magazine,” WWII eras. (“Be a Radio Expert! Many Make $30 $50 $75 featuring the new genre of a Week!” “Get into Aviation by Training at Home!” “scientifiction.” “Listerine Ends Husband’s Dandruff in 3 Weeks!” “I’ll Prove that YOU, too, can be a NEW MAN! – Charles Atlas.”) The business end of the pulps was notoriously inconstant and sometimes shady; magazines came into and went out of publication with little fanfare; they often changed genres or titles without advance notice. -

Science Fiction's Inception in Interwar Pulp Magazines

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-6-2021 Amazing Stories: Science Fiction’s Inception in Interwar Pulp Magazines Zachary Doe CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/760 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Amazing Stories: Science Fiction’s Inception in Interwar Pulp Magazines By Zachary Doe Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (English), Hunter College, The City University of New York 2021 04/17/2021 Professor Jeff Allred Thesis Sponsor 04/17/2021 Professor Alan Vardy Second Reader 2 The approach to the imaginary locality, or localized daydream, practiced by the genre of [Science Fiction] is a supposedly factual one. Columbus’ (technically or genealogically non-fictional) letter on the Eden he glimpsed beyond the Orinoco mouth, and Swift’s (technically non-factual) voyage to ‘Laputa, Balnibarbi, Glubbdubdrib, Luggnagg and Japan,’ stand at the opposite ends of a ban between imaginary and factual possibilities. Thus, SF takes off from a fictional (‘Literary’) hypothesis and develops it with extrapolating and totalizing (‘scientific’) rigor– in genre, Columbus and Swift are more alike than different. –Darko Suvin, “On the Poetics of the Science Fiction Genre” Science Fiction is not about the future; it uses the future as a narrative convention to present significant distortions of the present. -

Son-WSFA 181&2 Miller 1975-04-01

SON OF T H E ' W S*F A J 0 U R N A L .. SF/Fantasy News/Reviow 'Zine — 1st & 2nd Apr- ’75 Issues — 25^ each*, 10/$.2xP0 Editor St Publisher: Don Miller —------- Vol, 31, #Ts 1 & 2; Whole Nos. 181 &-182 In, This Issue — ' ' . IN‘ THIS ISSUE; IN BRIEF (misc. notes/announcements); COLOPHON .............. .. pg 1 THE'’ CON GAME: Mid-April 175 thru Early May 175 ................ .. -.............. -. =» pg 2 THE LOCAL SCENE; Radio Notes; Miscellany .......... .......................................... pp 2,1 BOOKWORLD: Book Reviews (SF/Fantasy, by Don D'Ammassa, Jim Goldfrank; Non-Fiction, by Jim Goldfrank; Mystery/Suspense/Adventure/etc,, by Don D'Ammassa, Sheila D'Ammassa); Review Extracts (SF/Fantagy, Non-Fiction); Books. Announced; Books Received; pp 3-10,1 MAGAZINARAMA: Prozines (& Somi-Prozines) Received .................— .. pp 11-13 THE AMATEUR PRESS: Fanzines Received ............................................a'.... pp lb-20 SF MART: Classified Ads ....................................... ...... pg 2u ON THE MOVE.: Changes-pf-Address, etc. ............. ............ pg 20 EN PASSANT: Lettercolumn (Don D'Ammassa, Martin Last, Floyd Poill/Mary M. Schmidt, WAHF's (Linda Bushyager, Camille Cazedessus, Tom Cobb, Don D'Ammassa, James Ellis, Jim Goldfrank, Tom Mason, Norbert Spel.ner. Howard Thompson, et al) ................................................................................ .. pp 21-22 BOOKWORLD: REVIEW EXTRACTS (Non-Fiction) (Cont. from pg. 6) — prospectors, and conquistadores. There's even a Manilla galleon which periodically emerges from the shifting sand dunes along Oregon's coast, only soon to vanish again, taking-.1 ' its treasure chests and bullion with it.' . , fast-moving and certainly diverting") THE LOCAL SCENE: MISCELLANY (Cont. from pg. 2) — p.mc 2h/h» ## Sleeper at Loyola College Student Center 7:30 & 9:30 p.m.