Microworlds: Building Powerful Ideas in the Secondary School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compiler Error Messages Considered Unhelpful: the Landscape of Text-Based Programming Error Message Research

Working Group Report ITiCSE-WGR ’19, July 15–17, 2019, Aberdeen, Scotland Uk Compiler Error Messages Considered Unhelpful: The Landscape of Text-Based Programming Error Message Research Brett A. Becker∗ Paul Denny∗ Raymond Pettit∗ University College Dublin University of Auckland University of Virginia Dublin, Ireland Auckland, New Zealand Charlottesville, Virginia, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Durell Bouchard Dennis J. Bouvier Brian Harrington Roanoke College Southern Illinois University Edwardsville University of Toronto Scarborough Roanoke, Virgina, USA Edwardsville, Illinois, USA Scarborough, Ontario, Canada [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Amir Kamil Amey Karkare Chris McDonald University of Michigan Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur University of Western Australia Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA Kanpur, India Perth, Australia [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Peter-Michael Osera Janice L. Pearce James Prather Grinnell College Berea College Abilene Christian University Grinnell, Iowa, USA Berea, Kentucky, USA Abilene, Texas, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT of evidence supporting each one (historical, anecdotal, and empiri- Diagnostic messages generated by compilers and interpreters such cal). This work can serve as a starting point for those who wish to as syntax error messages have been researched for over half of a conduct research on compiler error messages, runtime errors, and century. Unfortunately, these messages which include error, warn- warnings. We also make the bibtex file of our 300+ reference corpus ing, and run-time messages, present substantial difficulty and could publicly available. -

The Comparability Between Modular and Non-Modular

THE COMPARABILITY BETWEEN MODULAR AND NON-MODULAR EXAMINATIONS AT GCE ADVANCED LEVEL Elizabeth A Gray PhD INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 1 ABSTRACT The prime concern of this thesis is the comparability of two types of assessment now prevalent in Advanced level GeE examinations. The more conventional linear scheme assesses all candidates terminally, and the only way to improve the grade awarded is to re-take the whole examination. In contrast, the relatively new modular schemes of assessment include testing opportunities throughout the course of study. This not only has formative effects but allows quantifiable improvements in syllabus results through the medium of the resit option. There are obvious differences between the two schemes, but this does not necessarily imply that they are not comparable in their grading standards. It is this standard which the thesis attempts to address by considering the different variabilities of each of the schemes, and how these might impinge upon the outcomes of the grading process as evidenced in the final grade distributions. A key issue is that of legitimate and illegitimate variabilities - the former perhaps allowing an improvement in performance while maintaining grading standards; the latter possibly affecting the grading standard because its effect was not fully taken into account in the awarding process. By looking at a linear and modular syllabus in mathematics, the differences between the two are investigated, and although not fully generalisable, it is clear that many of the worries which were advanced when modular schemes were first introduced are groundless. Most candidates are seen to use the testing flexibility to their advantage, but there is little evidence of over-testing. -

The Education Column

The Education Column by Juraj Hromkovicˇ Department of Computer Science ETH Zürich Universitätstrasse 6, 8092 Zürich, Switzerland [email protected] Learn to Program?Program to Learn! Matthias Hauswirth Università della Svizzera italiana [email protected] Abstract Learning to program may make students more employable, and it may make them better thinkers. However, the most important reason for learning to program may well be that it enables an entirely new way of learning.1 1 Why Everyone Should Learn to Program We are in a gold rush in computer science education. Countless school districts, states, countries, non-profits, and startups rush to offer computer science, or cod- ing, for all. The goal—or gold?—too often is seen in empowering students to get great future-proof jobs. This first goal—programming to earn—is fine, but it is much too limited. A broader goal looks at computer science education as general education that helps students to become critical thinkers. Like the headmaster of my school, who recommended I study Latin because it would make me a better thinker. It probably did. And so did studying computer science. This second goal—programming to think—is great. However, I claim that there is a third, even greater, goal for teaching computer science to each and every person on the planet. Read on! 2 Computer Language as a Medium In “Computer Science: Reflections on the Field, Reflections from the Field” [6], Gerald Jay Sussman (MIT) writes an essay called “The Legacy of Computer Sci- ence.” There he cites from his own landmark programming textbook “Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs” (SCIP) [1]: 1 This article is based on a blog post previously published at https://medium.com/ @mathau/learning-to-program-programming-to-learn-c2c3d71d4d1d The computer revolution is a revolution in the way we think and in the way we express what we think. -

A Simplified Introduction to Virus Propagation Using Maple's Turtle Graphics Package

E. Roanes-Lozano, C. Solano-Macías & E. Roanes-Macías.: A simplified introduction to virus propagation using Maple's Turtle Graphics package A simplified introduction to virus propagation using Maple's Turtle Graphics package Eugenio Roanes-Lozano Instituto de Matemática Interdisciplinar & Departamento de Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales, Sociales y Matemáticas Facultad de Educación, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain Carmen Solano-Macías Departamento de Información y Comunicación Facultad de CC. de la Documentación y Comunicación, Universidad de Extremadura, Spain Eugenio Roanes-Macías Departamento de Álgebra, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain [email protected] ; [email protected] ; [email protected] Partially funded by the research project PGC2018-096509-B-100 (Government of Spain) 1 E. Roanes-Lozano, C. Solano-Macías & E. Roanes-Macías.: A simplified introduction to virus propagation using Maple's Turtle Graphics package 1. INTRODUCTION: TURTLE GEOMETRY AND LOGO • Logo language: developed at the end of the ‘60s • Characterized by the use of Turtle Geometry (a.k.a. as Turtle Graphics). • Oriented to introduce kids to programming (Papert, 1980). • Basic movements of the turtle (graphic cursor): FD, BK RT, LT. • It is not based on a Cartesian Coordinate system. 2 E. Roanes-Lozano, C. Solano-Macías & E. Roanes-Macías.: A simplified introduction to virus propagation using Maple's Turtle Graphics package • Initially robots were used to plot the trail of the turtle. http://cyberneticzoo.com/cyberneticanimals/1969-the-logo-turtle-seymour-papert-marvin-minsky-et-al-american/ 3 E. Roanes-Lozano, C. Solano-Macías & E. Roanes-Macías.: A simplified introduction to virus propagation using Maple's Turtle Graphics package • IBM Logo / LCSI Logo (’80) 4 E. -

Co-Teaching Computer Science Across Borders

Session 3 L@S ’20, August 12–14, 2020, Virtual Event, USA Co-Teaching Computer Science Across Borders: Human-Centric Learning at Scale Chris Piech Lisa Yan Lisa Einstein Stanford University Stanford University Stanford University Stanford, CA, USA Stanford, CA, USA Stanford, CA, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Ana Saavedra Baris Bozkurt Eliska Sestakova Stanford University Izmir Demokrasi Universitesi Czech Technical University Stanford, CA, USA Izmir, Turkey Prague, Czech Republic [email protected] [email protected] eliska.sestakova@fit.cvut.cz Ondrej Guth Nick McKeown Czech Technical University Stanford University Prague, Czech Republic Stanford, CA, USA ondrej.guth@fit.cvut.cz [email protected] ABSTRACT CCS Concepts Programming is fast becoming a required skill set for stu- •Social and professional topics ! Computing education; dents in every country. We present CS Bridge, a model for CS1; cross-border co-teaching of CS1, along with a correspond- ing open-source course-in-a-box curriculum made for easy INTRODUCTION localization. In the CS Bridge model, instructors and student- Computer science education has made substantial progress teachers from different countries come together to teach a towards the goal of CS for All in the United States, online, short, stand-alone CS1 course to hundreds of local high school and in some regions of the world. However, there is mounting students. The corresponding open-source curriculum has been evidence of a growing global digital divide, where access to specifically designed to be easily adapted to a wide variety of CS education is heavily dependant on which region you were local teaching practices, languages, and cultures. -

Papert's Microworld and Geogebra: a Proposal to Improve Teaching Of

Creative Education, 2019, 10, 1525-1538 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce ISSN Online: 2151-4771 ISSN Print: 2151-4755 Papert’s Microworld and Geogebra: A Proposal to Improve Teaching of Functions Carlos Vitor De Alencar Carvalho1,4, Lícia Giesta Ferreira De Medeiros2, Antonio Paulo Muccillo De Medeiros3, Ricardo Marinho Santos4 1State University Center of Western, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil 2CEFET/RJ, Valença, RJ, Brazil 3Rio de Janeiro Federal Institute (IFRJ), Pinheiral, RJ, Brazil 4Vassouras University, Vassouras, RJ, Brazil How to cite this paper: De Alencar Car- Abstract valho, C. V., De Medeiros, L. G. F., De Me- deiros, A. P. M., & Santos, R. M. (2019). This paper discusses how to improve teaching of Mathematics in Brazilian Papert’s Microworld and Geogebra: A Pro- schools, based on Seymour Papert’s Constructionism associated with Infor- posal to Improve Teaching of Functions. mation Technology tools. Specifically, this work introduces the construction- Creative Education, 10, 1525-1538. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2019.107111 ist microworld, a digital environment where students are able to build their knowledge interactively, in this case, using dynamic mathematics software Received: June 6, 2019 GeoGebra. Accepted: July 14, 2019 Published: July 17, 2019 Keywords Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and Microworld, GeoGebra, Seymour Papert, Information Technologies in Scientific Research Publishing Inc. Education This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Open Access 1. Introduction This research’s main goal is to present a proposal to help Brazilian teachers im- prove their educational practices. -

Polish Python: a Short Report from a Short Experiment Jakub Swacha Department of IT in Management, University of Szczecin, Poland [email protected]

Polish Python: A Short Report from a Short Experiment Jakub Swacha Department of IT in Management, University of Szczecin, Poland [email protected] Abstract Using a programming language based on English can pose an obstacle for learning programming, especially at its early stage, for students who do not understand English. In this paper, however, we report on an experiment in which higher-education students who have some knowledge of both Python and English were asked to solve programming exercises in a Polish-language-based version of Python. The results of the survey performed after the experiment indicate that even among the students who both know English and learned the original Python language, there is a group of students who appreciate the advantages of the translated version. 2012 ACM Subject Classification Social and professional topics → Computing education; Software and its engineering → General programming languages Keywords and phrases programming language education, programming language localization, pro- gramming language translation, programming language vocabulary Digital Object Identifier 10.4230/OASIcs.ICPEC.2020.25 1 Introduction As a result of the overwhelming contribution of English-speaking researchers to the conception and development of computer science, almost every popular programming language used nowadays has a vocabulary based on this language [15]. This can be seen as an obstacle for learning programming, especially at its early stage, for students whose native language is not English [11]. In their case, the difficulty of understanding programs is augmented by the fact that keywords and standard library function names mean nothing to them. Even in the case of students who speak English as learned language, they are additionally burdened with translating the words to the language in which they think. -

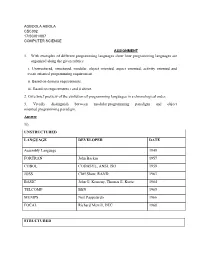

1. with Examples of Different Programming Languages Show How Programming Languages Are Organized Along the Given Rubrics: I

AGBOOLA ABIOLA CSC302 17/SCI01/007 COMPUTER SCIENCE ASSIGNMENT 1. With examples of different programming languages show how programming languages are organized along the given rubrics: i. Unstructured, structured, modular, object oriented, aspect oriented, activity oriented and event oriented programming requirement. ii. Based on domain requirements. iii. Based on requirements i and ii above. 2. Give brief preview of the evolution of programming languages in a chronological order. 3. Vividly distinguish between modular programming paradigm and object oriented programming paradigm. Answer 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN John Backus 1957 COBOL CODASYL, ANSI, ISO 1959 JOSS Cliff Shaw, RAND 1963 BASIC John G. Kemeny, Thomas E. Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS Neil Pappalardo 1966 FOCAL Richard Merrill, DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL 58 Friedrich L. Bauer, and co. 1958 ALGOL 60 Backus, Bauer and co. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada United States Department of Defence 1980 Accent R NIS 1980 Action! Optimized Systems Software 1983 Alef Phil Winterbottom 1992 DASL Sun Micro-systems Laboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL W Niklaus Wirth, Tony Hoare 1966 APL Larry Breed, Dick Lathwell and co. 1966 ALGOL 68 A. Van Wijngaarden and co. 1968 AMOS BASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin Stiropoulos 1990 Alice ML Saarland University 2000 Agda Ulf Norell;Catarina coquand(1.0) 2007 Arc Paul Graham, Robert Morris and co. 2008 Bosque Mark Marron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* Thinking Machine 1987 Actor Charles Duff 1988 Aldor Thomas J. Watson Research Center 1990 Amiga E Wouter van Oortmerssen 1993 Action Script Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript Andreas Jönsson 2003 Boo Rodrigo B. -

4 MICRO WORLDS: TRANSFORMING EDUCA TION 1 Seymour Papert

MICRO WORLDS: 4 TRANSFORMING EDUCA TION 1 Seymour Papert Arts and Media Technology Center Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge. MA Looking at how computers are used in education, one is tempted to start classifying. It's a little dangerous to do this, but I would like to start off with a very crude classification of three ways of using computers, just to place a certain set of problems into perspective. First, as tutorials in one sense or another - which is by far the most widespread, best known, and earliest use - where the computer serves as a sort of mechanized instructor. Secondly, as tools for doing something else: as calculators, word processors, simulators, or whatever. And thirdly, a different concept altogether: as microworlds. Here I shall concentrate on the notion of microworld and talk about its relations both to computers and to theories of learning. The other uses of computers surely have a role - but they are not what will revolutionize education. One microworld which is already widely known is the Logo turtle mi croworld. Briefly, this world is inhabited by a small object on the screen. In some versions, it is shaped like a triangle, in others, like an actual turtle. To make it move and draw lines, you talk to it by typing commands on the keyboard. For example, if you say FORWARD 50, the turtle will move in the direction it's facing and draw a line 50 units long, 50 "turtle steps" children might say. Then if you say RIGHT 90, it will turn 90 degrees. And then you can tell it to go forward again, or back, turn through any angle, or lift its pen up so it moves without leaving a trace. -

Logo Philosophy and Implementation TABLE of CONTENTS

Logo Philosophy and Implementation TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION What is Logo? Who Needs It? by Seymour Papert ................................................... IV THE COMPUTER IN COSTA RICA: A New Door to Educational and Social Opportunities Photographs accompanying each chapter are used by Clotilde Fonseca ........................................................... 2 with permission of the authors. THE SAINT PAUL LOGO PROJECT: The samba school photograph in the Brazil chapter is used with permission An American Experience of the photographer John Maier Jr. by Geraldine Kozberg and Michael Tempel ............................ 22 THE RUSSIAN SCHOOL SYSTEM AND THE LOGO APPROACH: Two Methods Worlds Apart Graphic design by Le groupe Flexidée by Sergei Soprunov and Elena Yakovleva ............................... 48 © Logo Computer Systems Inc. 1999 A LOGO POSTCARD FROM ARGENTINA All rights reserved. by Horacio C. Reggini .................................................................... 78 No part of the document contained herein may be reproduced, stored LOGO IN AUSTRALIA: in retrieval systems or transmitted, in any form or by any means, A Vision of Their Own photocopying, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without by Jeff Richardson ............................................................ 96 the prior approval from Logo Computer Systems Inc. THE CONSTRUCTIONIST APPROACH: Legal deposit, 1st semester 1999 The Integration of Computers ISBN 2-89371-494-3 in Brazilian Public Schools Printed 2-99 by Maria Elizabeth B. Almeida -

Cross-Listed with Computer Science) Spring 2005 Wednesday, 1:30-4:30 PM Annenberg 303, North Learning Studio

A CONSTRUCTIONIST APPROACH TO THE DESIGN OF LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS Learning Sciences 426 (cross-listed with Computer Science) Spring 2005 Wednesday, 1:30-4:30 PM Annenberg 303, North Learning Studio Professor: Uri Wilensky Address: Annenberg 311 Phone: 847-467-3818 E-mail: [email protected] TAs: Paulo Blikstein (467-3859 [email protected]) & Josh Unterman (467-2816 [email protected]) Course Web Site: http://ccl.northwestern.edu/courses/cd2005/ Course Instructors: [email protected] Course Members (students and faculty): [email protected] Course Description This course is a hands-on practicum in designing and building technology-enabled curricula and/or educational software. We will use many rich software toolkits designed to enable novice programmers to get their “hands dirty” doing iterative software design. In addition to the hands-on component, the course is also designed to introduce you to the Constructionist Learning design perspective. This perspective, first named by Seymour Papert and greatly influenced by the work of Jean Piaget, is very influential in the learning sciences today. The Constructionist approach starts with the assumption that teaching cannot successfully proceed by simply transferring knowledge to students’ heads. Skillful teaching starts with the current state of knowledge of the student. In order for students to learn effectively, they need to construct the knowledge structures for themselves. In this class, we will engage in the construction of artifacts and, through such constructions, explore and evaluate the design of construction kits and tools to enable learners to construct motivating and powerful artifacts. In the spirit of Constructionism, students in this course will self-construct their own understanding of the educational software and of the literature through constructing artifacts (both physical and virtual) and engaging in reflective discussion of both the artifacts and the tools used to construct them. -

Direct Manipulation of Turtle Graphics

Master Thesis Direct Manipulation of Turtle Graphics Matthias Graf September 30, 2014 Supervisors: Dr. Veit Köppen & Prof. Dr. Gunter Saake Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg Prof. Dr. Marian Dörk University of Applied Sciences Potsdam Abstract This thesis is centred around the question of how dynamic pictures can be created and manipulated directly, analogous to drawing images, in an attempt to overcome traditional abstract textual program representations and interfaces (coding). To explore new ideas, Vogo1 is presented, an experimental, spatially-oriented, direct manipulation, live programming environment for Logo Turtle Graphics. It allows complex abstract shapes to be created entirely on a canvas. The interplay of several interface design principles is demonstrated to encourage exploration, curiosity and serendipitous discoveries. By reaching out to new programmers, this thesis seeks to question established programming paradigms and expand the view of what programming is. 1http://mgrf.de/vogo/ 2 Contents 1 Introduction5 1.1 Research Question.................................6 1.2 Turtle Graphics..................................6 1.3 Direct Manipulation................................8 1.4 Goal......................................... 10 1.5 Challenges..................................... 12 1.6 Outline....................................... 14 2 Related Research 15 2.1 Sketchpad..................................... 15 2.2 Constructivism................................... 16 2.3 Logo........................................ 19 2.4