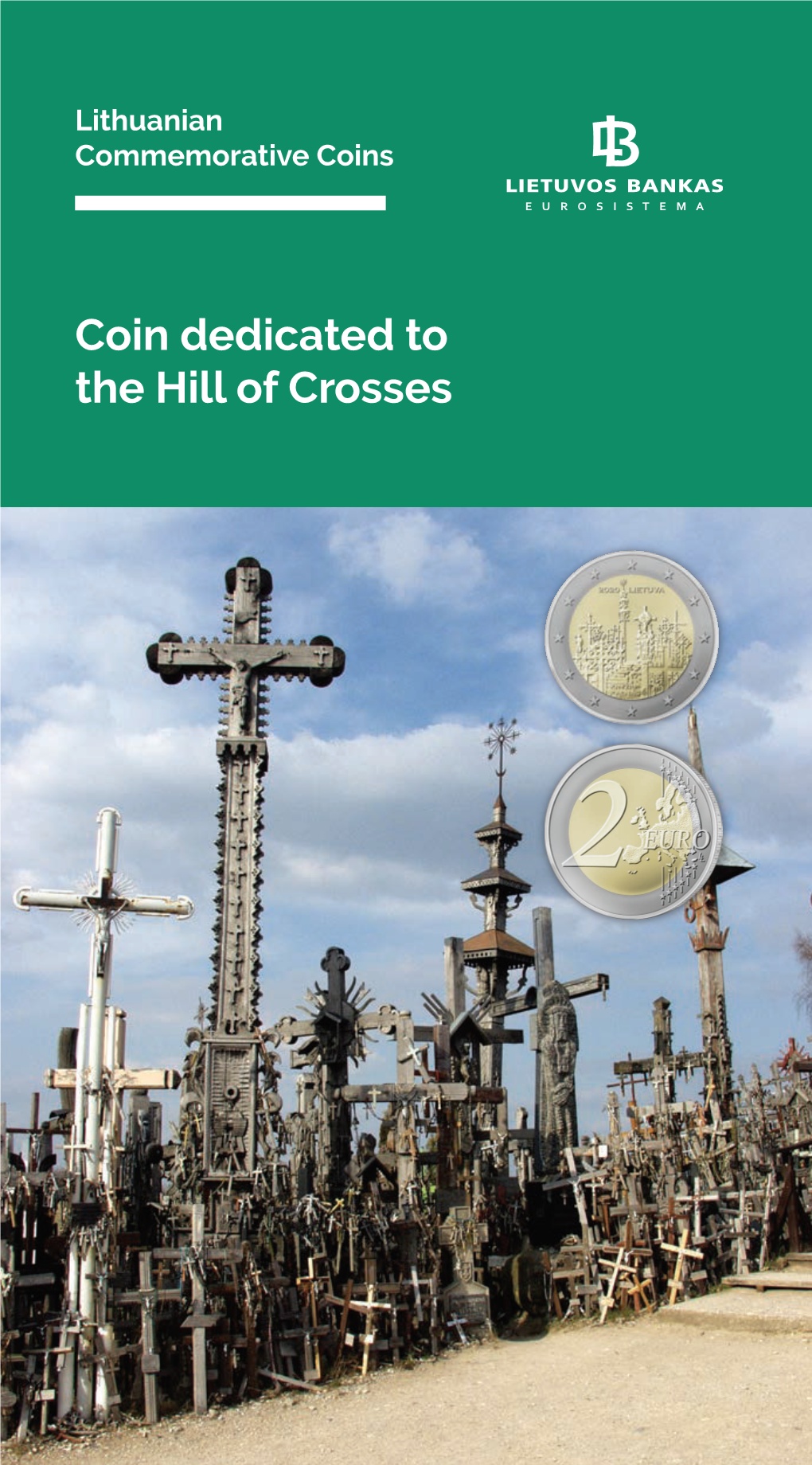

Coin Dedicated to the Hill of Crosses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irena Krzywicka and Hiratsuka Raichō – Life, Activity, Work

INTERCULTURAL RELATIONS ◦ RELACJE MIĘDZYKULTUROWE ◦ 2020 ◦ 2 (8) https://doi.org/10.12797/RM.02.2020.08.11 Zofia Prażuch1 IRENA KRZYWICKA AND HIRATSUKA RAICHŌ – LIFE, ACTIVITY, WORK Abstract The main aim of this article is to draw a comparison between two female fig- ures – Hiratsuka Raichō from Japan and Irena Krzywicka from Poland. Despite the fact that these two women lived in different countries and came from to- tally different cultural backgrounds, they fought for a better future for women. Both Irena Krzywicka and Hiratsuka Raichō lived during a difficult time of war and were witnesses to dynamic political and social changes in their respective countries. As in historical terms, this was the very beginning of feminist move- ment, both in Poland and Japan, their lives and activities fall within the period of the first wave of feminism. Key words: Hiratsuka Raichō, Irena Krzywicka, Poland, Japan, feminism, mar- riage, motherhood, women’s activism INTRODUCTION At the beginning of the 20th century, a trend towards women gaining emancipation became visible, one which enabled women to obtain an ap- propriate education and professional positions, as well as allowing new op- portunities to open up for them. Over the years, increased activism has re- sulted in the regulation of women’s rights in various areas of life. Activities such as the fight for gender equality, marriage, motherhood, birth control, pacifism, and gaining the right to participate in political life intensified. As women began to unite, support each other and set up various char- ity organisations and trade unions, they became politically active. As this 1 MA Student; Jagiellonian University in Kraków; ORCID: 0000-0002-0249-3131; [email protected]. -

Acta 114.Indd

ARCHIVE* In the interwar years, social sciences developed in East Central Europe along with nation-states and their increasingly apparent weaknesses. Polish sociolo- gists of the period, whose intellectual formation dated back to the last decades of the European empires, coped with the challenges of their time and commented on modern ideologies, mass movements, sudden social dislocations, and economic depressions. Stefan Czarnowski (1879–1937), a member of the Durkheim school and a disciple of Henri Hubert (1872–1927) and Marcel Mauss (1872–1950), was one of them. A historian of culture, he specialised in Celtic history and was among the founding fathers of Polish sociology.1 His outstand- ing works include Le culte des héros et ses conditions sociales: Saint Patrick, héros national de l’Irlande;2 a collection of essays published post- humously as Kultura [Culture],3 and a methodological study Założenia meto- dologiczne w badaniu rozwoju społeczeństw ludzkich [ Methodological * The work on this introduction was supported by NPRH grant no. 0133/ NPRH4/H1b/83/2015. 1 For a complete edition of Stefan Czarnowski’s works, see Stefan Czarnowski, Dzieła, 5 vols., ed. by Nina Assorodobraj and Stefan Ossowski (Warszawa, 1956). German scholar Max Spohn is presently working on a fi rst complete intellectual biography of Czarnowski. The existing reliable discussions include: Nina Assoro- dobraj, ‘Życie i dzieło Stefana Czarnowskiego’, in Czarnowski, Dzieła, v, 105–56; Marek Jabłonowski (ed.), Stefan Czarnowski z perspektywy siedemdziesięciolecia (War- szawa, 2008); Kornelia Kończal and Joanna Wawrzyniak, ‘Posłowie’/‘Postface’, in Stefan Czarnowski, Listy do Henri Huberta i Marcela Maussa (1905–1937) / Lettres à Henri Hubert et à Marcel Mauss (1905–1937), ed. -

Work Ethos Or Counter-Ideology of Work? Danuta Walczak-Duraj*

Warsaw Forum of Economic Sociolog y 7:1(13) Spring 2016 Warsaw School of Economics; Collegium of Socio-Economics; Institute of Philosophy, Sociolog y and Economic Sociolog y Work Ethos or Counter-ideology of Work? Danuta Walczak-Duraj* Abstract While attempting to answer a question in the title of this paper !rst of all, basic intentions that inspired to formulate such a topic should be explained. "e bottom line is whether in the re#ections of representatives of sociology of work or sociology of economy, referring to contextual perception and analysis of labour relations in Poland, some focus should be put on the issues concerning rede!ning the essence and content of work ethos, or rather on an analysis of a set of factors, both of endogenic and exogenous nature, which contribute to a broadly understood counter-ideology of work. "erefore, this paper presents an attempt to indicate twofold types of phenomena and processes; on the one hand, those that in#uence a process of individualization and fragmentation of work ethos in Poland; on the other one, those which a$ect content of major motivation and interpretation schemes mentioned by employees, which may become presumptions to the development of counter-ideology of work. In such circumstances, a role of work ethos in creating economic harmony, which is a special case of axionormative harmony, decreases signi!cantly and loses its explicitly social character while increasingly becoming only one of dimensions of individual identity, professional biography or a personality pro!le of an individual. -

WA303 27640 2010-100 APH-08 O

Acta Poloniae Historica 100, 2009 PL ISSN 0001-6892 Magdalena Micińska THE POLISH INTELLIGENTSIA IN THE YEARS 1864-1918 The middle 1860s were an important turning-point in the history of the Polish nation, especially that of its educated elites. The tragic defeat of the January Uprising (1863-4) was followed by a period of heavy political repressions, profound social changes, economic challenges and intellectual revaluations. This period faced the Polish intellectual elites with the greatest challenges in their history and at the same time it began the decades when this stratum enjoyed a hitherto unknown social prestige. This was a time when the intelligentsia set itself tasks to which it could not aspire ever after. The people in the area within Russian partition underwent brutal repressions that affected not only the intellectual elite, but society as a whole. The human losses suffered in insurgent battles and summary executions were augmented by ensuing deportations to Siberia, the Caucasus and into the Russian Empire, which embraced about 40,000 insurgents and members of their families, eliminating them for many years, sometimes for ever, from the country’s life. Arrests and deportations were accompanied by confiscations of property. It is very hard to es tablish the percentage of the intelligentsia among the deportees (the Russian sources did not distinguish this social category), but certainly they included the most active individuals, those most conscious of and dedicated to the idea of a prompt reconstruction of independent Poland. Soon after the downfall of the January Uprising the Russians started a process of the liquidation of the separate character of Congress Poland. -

Migration to the Self: Education, Political Economy, and Religious Authority in Polish Communities by Kathleen Wroblewski a Diss

Migration to the Self: Education, Political Economy, and Religious Authority in Polish Communities by Kathleen Wroblewski A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Brian Porter-Szűcs, Chair Associate Professor Robert Bain Professor Howard Brick Professor Jeffrey Veidlinger Mary Kathleen Wroblewski [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-5001-8829 © Kathleen Wroblewski 2018 DEDICATION For Chad and Zosia, with love ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS When Josh Cole called me to let me know I had been admitted to Michigan, he ended our conversation by asking me to inform the department as soon as I had made my decision. I laughed and told him that as UM was the only place I had applied to, I’d likely accept. While I wouldn’t necessarily recommend that unorthodox approach to others, I have no regrets. My experience at Michigan has been a joy, and I am profoundly grateful to have had the opportunity to work with a number of exceptional scholars. My committee has been supportive from start to finish. First and foremost, I need to thank my advisor, Brian Porter-Szűcs, for his mentorship over the years. Brian supervised my undergraduate honors thesis at UM, and it was this experience that convinced me I wanted to pursue a career in history. I appreciate the combination of intellectual rigor, professionalism, and compassion that Brian brings to graduate mentoring, and I’ve no doubt that I’ll draw from his strong example as I transition to my next role as assistant professor. -

Flying Universities: Educational Movements in Poland 1882-1905 and 1977-1981, a Socio-Historical Analysis

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1997 Flying Universities: Educational Movements in Poland 1882-1905 and 1977-1981, a Socio-Historical Analysis Gregory A. Lukasik Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, and the Educational Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lukasik, Gregory A., "Flying Universities: Educational Movements in Poland 1882-1905 and 1977-1981, a Socio-Historical Analysis" (1997). Master's Theses. 3379. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3379 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLYING UNIVERSITIES: EDUCATIONAL MOVEMENTS IN POLAND 1882-1905 AND 1977-1981, A SOCIO-HISTORICAL ANALYSIS by Gregory A. Lukasik A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements forthe Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology West em Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1997 FL YING UNIVERSITIES: EDUCATIONAL MOVEl\.,ffiNTSIN POLAND 1882-1905 AND 1977-1981, A SOCIO-HISTORICAL ANALYSIS Gregory A. Lukasik, M.A. WesternMichigan University, 1997 In Poland in 1977, a group of intellectuals formed an independent educational enterprise under the name "Flying University." Interestingly, the original "Flying University" was organized by a group of radical professorsnearly a century earlier, at a time when the Polish state disappeared fromthe political map of Europe. I was interested in seeing whether the two were the same, as their common name would suggest, or if they differedin any respect. -

Irena Krzywicka and Hiratsuka Raichō – Life, Activity, Work

INTERCULTURAL RELATIONS ◦ RELACJE MIĘDZYKULTUROWE ◦ 2020 ◦ 2 (8) https://doi.org/10.12797/RM.02.2020.08.11 Zofia Prażuch1 IRENA KRZYWICKA AND HIRATSUKA RAICHŌ – LIFE, ACTIVITY, WORK Abstract The main aim of this article is to draw a comparison between two female fig- ures – Hiratsuka Raichō from Japan and Irena Krzywicka from Poland. Despite the fact that these two women lived in different countries and came from to- tally different cultural backgrounds, they fought for a better future for women. Both Irena Krzywicka and Hiratsuka Raichō lived during a difficult time of war and were witnesses to dynamic political and social changes in their respective countries. As in historical terms, this was the very beginning of feminist move- ment, both in Poland and Japan, their lives and activities fall within the period of the first wave of feminism. Key words: Hiratsuka Raichō, Irena Krzywicka, Poland, Japan, feminism, mar- riage, motherhood, women’s activism INTRODUCTION At the beginning of the 20th century, a trend towards women gaining emancipation became visible, one which enabled women to obtain an ap- propriate education and professional positions, as well as allowing new op- portunities to open up for them. Over the years, increased activism has re- sulted in the regulation of women’s rights in various areas of life. Activities such as the fight for gender equality, marriage, motherhood, birth control, pacifism, and gaining the right to participate in political life intensified. As women began to unite, support each other and set up various char- ity organisations and trade unions, they became politically active. As this 1 MA Student; Jagiellonian University in Kraków; ORCID: 0000-0002-0249-3131; [email protected]. -

Konferencja.Europejki.W.Polityce

Instytut Historyczny Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego Institut für Geschichte Technische Universität Dresden Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich serdecznie zapraszają na międzynarodową konferencję naukową, która odbędzie się w dniach 12 grudnia 2016 roku: Europejki w polityce od czasów nowożytnych do współczesności Wykłady otwarte: Czas: 1 XII 2016 r., godz. 17:30 Miejsce: Barbara: infopunkt, kawiarnia, kultura dr Dietlind Hüchtker (Leipzig) Performance und Performativität. Politische Bewegungen in Galizien Performans i performatywność. Ruchy polityczne w Galicji (wykład tłumaczony) Czas: 2 XII 2016 r., godz. 16:30 M i e j s c e : Z a k ł ad Narodowy im. Ossolińskich dr Dobrochna Kałwa (Warszawa) Feministyczne utopie i dystopie – historia polskich debat wokół politycznej partycypacji kobiet Day I 1 XII 2016 Judith Märksch (TU Dresden) Geschlecht, Klasse und Ethnie auf dem Arbeitsmarkt der Instytut Historyczny Bundesrepublik Deutschland 19641969 Szewska 49, Wrocław Gender, Class and Race at the Labour Market of the Federal Republic of Gemany 14:0014:30 Conference opening Dorota Wiśniewska (UWr) commentary Conference programme prof. Rościsław Żerelik (UWr) prof. Susanne Schötz (TU Dresden) Jessica Bock (TU Dresden) Der lange dr hab. Leszek Ziątkowski, prof. UWr. (UWr) Atem. Der ostdeutsche Frauenaufbruch Europejki w polityce od czasów dr Angelique LeszczawskiSchwerk (TU Dresden) zwischen Pluralisierung, Professionalisierung und institutionelle Integration am Beispiel nowożytnych do współczesności 14:3015:10 Session I Leipzigs in den 1990er -

Nationalism and Archaeology in Europe

Margarita Diaz-Andreu, Timothy Champion, eds.. Nationalism and Archaeology in Europe. Boulder and San Francisco: Westview Press, 1996. vi + 314 pp. $59.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-8133-3051-8. Reviewed by Charles C. Kolb Published on H-SAE (September, 1997) Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein This book is neither a history of archaeologi‐ are those of the reviewer and not of his employer cal research--as in the tradition of the writings of or any other federal agency. Because this is an Brew (1968), Daniel (1975), Trigger (1989), or Wil‐ electronic book review in ASCII format, it is not ley and Sabloff (1993)--nor is it a summary of Eu‐ possible to insert appropriate accents and diacriti‐ ropean archaeology in the manner of the late Stu‐ cal marks, and this reviewer offers his apologies art Piggott's (1966) well-known text or Phillips' to the contributors. (1980) more recent synthesis. From another per‐ Nationalism and Archaeology in Europe spective, it is not a methodical review of archaeol‐ ogy as a science (see Pollard and Heron 1996). Introduction However, what we do have is a well-crafted set of In this assessment, I shall provide introducto‐ social science and humanities-oriented essays that ry comments, consider the scope and place of the collectively report the development of archaeolo‐ compendium in sociocultural history, summarize gy as a discipline in the context of national politi‐ the salient points from each of the essays, and cal history for several European polities. The book then assess the book as a whole. I believe that the is similar in scope to Kohl and Fawcett's edited set significance of the essays in the volume goes well of nation-state case studies entitled Nationalism, beyond European studies and further afield than Politics, and the Practice of Archaeology (1995) merely the history of archaeology or perceptions which contains fve chapters on western Europe, and theories about the nation state and its agen‐ four on eastern Europe and Eurasia, and four on cies and institutions. -

Ludwika Karpińska, “Polish Lady Philosopher” – a Forgotten Forerunner of Polish Psychoanalysis

Psychiatr. Pol. ONLINE FIRST Nr 27 Published ahead of print 30 June, 2015 www.psychiatriapolska.pl ISSN 0033-2674 (PRINT), ISSN 2391-5854 (ONLINE) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12740/PP/OnlineFirst/44946 Ludwika Karpińska, “Polish Lady Philosopher” – a forgotten forerunner of Polish psychoanalysis Edyta Dembińska, Krzysztof Rutkowski Department of Psychotherapy, Jagiellonian University Medical College Summary The paper presents the profile of the psychologist, Ludwika Karpińska-Woyczyńska, the first Polish woman who acted for the popularisation of psychoanalysis and experimental psy- chology. Karpińska belonged to the first generation of the “Polish Freudians”, a group which also involved Ludwik Jekels, Stefan Borowiecki, Herman Nunberg, Jan Nelken and Karol de Beaurain. Karpińska’s difficult path to gain higher education will be presented. The paper lays an emphasis on Karpińska’s contribution to the development of the international psychoa- nalysis and offers an overview of her most significant psychoanalytic publications (Polish and foreign ones) up to the outbreak of World War I. It demonstrates her participation in scientific conferences and collaboration with the most important psychoanalytical centres in Zurich and Vienna together with their representatives (Jung, Freud, Jekels) drawing simultaneous attention to the broader historical background of the presented events. Karpińska’s post-war work was inextricably linked to the research on intelligence quotient of children and youth and psychotechnical studies. Furthermore, the paper illustrates the activities of the Municipal Psychological Lab in Lodz, where Karpińska was a Head between 1920 and 1930, as well as her scientific achievements in intelligence quotient research, most significant publications of 1921-1930, her collaboration with foreign centres of a similar profile and the efforts she made to establish the Vocational Guidance Service. -

LIFE and CHIMERA: FRAMING MODERNISM in POLAND By

LIFE AND CHIMERA: FRAMING MODERNISM IN POLAND by JUSTYNA DROZDEK Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Anne Helmreich Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August, 2008 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________ candidate for the ______________________degree *. (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Copyright © 2008 by Justyna Drozdek All rights reserved To mama and tata Table of Contents List of Figures 2 Acknowledgements 7 Abstract 9 Introduction 11 Chapter 1: Poland: A Historical and Artistic Context 38 Chapter 2: Life’s Editorial Directions: Crafting a Modernist Journal 74 Chapter 3: Life’s Visual Program: From Tropes to “Personalities” 124 Chapter 4: Chimera and Zenon Przesmycki’s Polemical Essays: Artistic Ideals 165 Chapter 5: Chimera’s Visual Program: Evocation and the Imagination 210 Conclusion 246 Appendix A: Tables of Contents for Life (1897-1900) 251 Appendix B: Tables of Contents for Chimera (1901-1907) 308 Figures 341 Selected Bibliography 389 1 List of Figures Figure 1. Jan Matejko. Skarga’s Sermon [Kazanie Skargi]. 1864. Oil on canvas. 224 x 397 cm. Royal Castle, Warsaw. Figure 2. Karel Hlaváček. Cover for Moderní revue. 1897. Figure 3. Wojciech Weiss. Youth (Młodość). 1899. Reproduced in Life 4, no. 1 (1900): 2. Figure 4. Gustav Vigeland. Hell. 1897. Bronze. National Galley, Oslo. Two fragments of the relief were reproduced in Life 3, 7 (1899). -

Introduction

TT 67-56012 SELECTED WORKS of Janusz Korczak PUBLISHED FOR THE NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION, WASHINGTON, D.C., BY THE SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS FOREIGN COOPERATION CENTER OF THE CENTRAL INSTITUTE FOR SCIENTIFIC, TECHNICAL AND ECONOMIC INFORMATION WARSAW, POLAND, 1967 1 Table of Contents PREFACE ............................................................................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 12 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.................................................................................................................28 THE APPLICATION .........................................................................................................................29 EDUCATIONAL FACTORS.............................................................................................................33 Introductory Remarks .................................................................................................................33 I. Public School - First Grade.................................................................................................35 II. Kindergarten and First Grade In A Private School For Girls ...................................38 III. Helcia ......................................................................................................................................42 IV. Stefan......................................................................................................................................