The Regional Uniqueness of English Field Systems?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bridge Barn Spinks Lane | Heydon | Norfolk | NR11 6RF BIG SKY COUNTRY

Bridge Barn Spinks Lane | Heydon | Norfolk | NR11 6RF BIG SKY COUNTRY “Wide open horizons, far reaching views, spectacular sunrises enjoyed from your door, there’s no light pollution and no neighbours to disturb, if you want the perfect paradise, this barn you’ll adore. A home with real heart, finished with attention to detail, the sense of quality throughout is clear, while the outbuilding and plot have potential in spades, the location an attraction and a place to hold dear.” KEY FEATURES • An Impressive and Versatile Converted Barn, standing in 2.75 acres of Formal Gardens • Four Bedrooms; Two Bathrooms; Two Receptions • Stunning Open Plan Kitchen; Separate Utility • Contemporary Wooden Staircase; Fireplace with Wood Burner • A wonderful Secluded Location, with No Near Neighbours, yet within Striking Distance of the Market Town of Holt • A Large Range of Outbuildings; Triple Cart Lodge; Additional Parking • Stunning Views in All Directions • The Accommodation extends to 2,838sq.ft • Energy Rating: E On a quiet lane surrounded by open countryside, this barn-style home sits in just under three acres of land, including a large workshop with office and full plumbing. It’s all set between the attractive and desirable towns of Aylsham and Holt, close to the North Norfolk coast and to a number of pretty villages. Whether it’s walking or stargazing, growing your own or horse riding, whether you want a traditional home or a modern build, a workshop or a large garden, this one ticks so many boxes and really has to be seen to be fully appreciated. The Character And The Contemporary This is effectively a modern home, having been built from the site of a bungalow around a decade ago. -

Marriott's Way Walking and Cycling Guide

Marriott’s Way Walking and Cycling Guide 1 Introduction The routes in this guide are designed to make the most of the natural Equipment beauty and cultural heritage of Marriott’s Way, which follows two disused Even in dry weather, a good pair of walking boots or shoes is essential for train lines between the medieval city of Norwich and the historic market the longer routes. Some of Marriott’s Way can be muddy so in some areas a town of Aylsham. Funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, they are a great way road bike may not be suitable and appropriate footwear is advised. Norfolk’s to delve deeper into this historically and naturally rich area. A wonderful climate is drier than much of the county but unfortunately we can’t array of habitats await, many of which are protected areas, home to rare guarantee sunshine, so packing a waterproof is always a good idea. If you are wildlife. The railway heritage is not the only history you will come across, as lucky enough to have the weather on your side, don’t forget sun cream and there are a series of churches and old villages to discover. a hat. With loops from one mile to twelve, there’s a distance for everyone here, whether you’ve never walked in the countryside before or you’re a Other considerations seasoned rambler. The landscape is particularly flat, with gradients being kept The walks and cycle loops described in these pages are well signposted to a minimum from when it was a railway, but this does not stop you feeling on the ground and detailed downloadable maps are available for each at like you’ve had a challenge. -

Beech Grove NORWICH, NORFOLK

Beech Grove NORWICH, NORFOLK A collection of 2 & 3 bedroom Shared Ownership homes situated within the quaint village of Horsford A home of your own ww Welcome to Contents Beech Grove Welcome to Beech Grove 3 Nestled in a village six miles north of Norwich, you’ll find an attractive new community of houses. Built in the traditional style, yet designed for contemporary living, Living at Beech Grove 4 Beech Grove offers the perfect location to put down roots and enjoy country life. Local area 6 This collection of two and three bedroom houses are Site plan 10 beautifully designed in a traditional style, yet full of modern touches. Every home has been built to the Floor plans 12 highest standards and the site has been carefully landscaped to create shared spaces that build a true Specification 16 sense of community. Legal & General Affordable Homes is offering a unique 18 Shared Ownership explained opportunity to purchase a new home here through Shared Ownership. Thanks to this scheme, you can own your A guide to owning your own home 20 home with a lower deposit than is required to buy outright or with other buying schemes. About Legal & General Affordable Homes 22 The village of Horsford 2 3 Living at Beech Grove Beautifully designed Town and Country Homes are traditionally built and designed Horsford is a rural village in the stunning with your lifestyle in mind. Norfolk countryside and just 6 miles to the bustling city of Norwich. Sit back and make plans Natural choice The neutral décor gives you the chance to Live on the edge of a village looking out make your own decisions about colours onto farmland, with woods nearby. -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 20.3 Socc Stakeholder Mailing List

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 20.3 SoCC Stakeholder Mailing List Applicant: Norfolk Vanguard Limited Document Reference: 5.1 Pursuant to APFP Regulation: 5(2)(q) Date: June 2018 Revision: Version 1 Author: BECG Photo: Kentish Flats Offshore Wind Farm This page is intentionally blank. Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Appendices Parish Councils Bacton and Edingthorpe Parish Council Witton and Ridlington Parish Council Brandiston Parish Council Guestwick Parish Council Little Witchingham Parish Council Marsham Parish Council Twyford Parish Council Lexham Parish Council Yaxham Parish Council Whinburgh and Westfield Parish Council Holme Hale Parish Council Bintree Parish Council North Tuddenham Parish Council Colkirk Parish Council Sporle with Palgrave Parish Council Shipdham Parish Council Bradenham Parish Council Paston Parish Council Worstead Parish Council Swanton Abbott Parish Council Alby with Thwaite Parish Council Skeyton Parish Council Melton Constable Parish Council Thurning Parish Council Pudding Norton Parish Council East Ruston Parish Council Hanworth Parish Council Briston Parish Council Kempstone Parish Council Brisley Parish Council Ingworth Parish Council Westwick Parish Council Stibbard Parish Council Themelthorpe Parish Council Burgh and Tuttington Parish Council Blickling Parish Council Oulton Parish Council Wood Dalling Parish Council Salle Parish Council Booton Parish Council Great Witchingham Parish Council Aylsham Town Council Heydon Parish Council Foulsham Parish Council Reepham -

North Norfolk District Council (Alby

DEFINITIVE STATEMENT OF PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY NORTH NORFOLK DISTRICT VOLUME I PARISH OF ALBY WITH THWAITE Footpath No. 1 (Middle Hill to Aldborough Mill). Starts from Middle Hill and runs north westwards to Aldborough Hill at parish boundary where it joins Footpath No. 12 of Aldborough. Footpath No. 2 (Alby Hill to All Saints' Church). Starts from Alby Hill and runs southwards to enter road opposite All Saints' Church. Footpath No. 3 (Dovehouse Lane to Footpath 13). Starts from Alby Hill and runs northwards, then turning eastwards, crosses Footpath No. 5 then again northwards, and continuing north-eastwards to field gate. Path continues from field gate in a south- easterly direction crossing the end Footpath No. 4 and U14440 continuing until it meets Footpath No.13 at TG 20567/34065. Footpath No. 4 (Park Farm to Sunday School). Starts from Park Farm and runs south westwards to Footpath No. 3 and U14440. Footpath No. 5 (Pack Lane). Starts from the C288 at TG 20237/33581 going in a northerly direction parallel and to the eastern boundary of the cemetery for a distance of approximately 11 metres to TG 20236/33589. Continuing in a westerly direction following the existing path for approximately 34 metres to TG 20201/33589 at the western boundary of the cemetery. Continuing in a generally northerly direction parallel to the western boundary of the cemetery for approximately 23 metres to the field boundary at TG 20206/33611. Continuing in a westerly direction parallel to and to the northern side of the field boundary for a distance of approximately 153 metres to exit onto the U440 road at TG 20054/33633. -

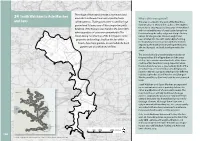

24 South Walsham to Acle Marshes and Fens

South Walsham to Acle Marshes The village of Acle stands beside a vast marshland 24 area which in Roman times was a great estuary Why is this area special? and Fens called Gariensis. Trading ports were located on high This area is located to the west of the River Bure ground and Acle was one of those important ports. from Moulton St Mary in the south to Fleet Dyke in Evidence of the Romans was found in the late 1980's the north. It encompasses a large area of marshland with considerable areas of peat located away from when quantities of coins were unearthed in The the river along the valley edge and along tributary Street during construction of the A47 bypass. Some valleys. At a larger scale, this area might have properties in the village, built on the line of the been divided into two with Upton Dyke forming beach, have front gardens of sand while the back the boundary between an area with few modern impacts to the north and a more fragmented area gardens are on a thick bed of flints. affected by roads and built development to the south. The area is basically a transitional zone between the peat valley of the Upper Bure and the areas of silty clay estuarine marshland soils of the lower reaches of the Bure these being deposited when the marshland area was a great estuary. Both of the areas have nature conservation area designations based on the two soil types which provide different habitats. Upton Broad and Marshes and Damgate Marshes and Decoy Carr have both been designated SSSIs. -

Spacious Linked Barn Conversion

SPACIOUS LINKED BARN CONVERSION FOX BARN, HORSFORD, NORFOLK The Property This spacious linked barn conversion is nearing completion to a high standard and is set in a quiet semi-rural location, on the edge of the village of Horsford. The main body of the barn is oak clad and has been thatched. The additional single storey wings have tiled roofs and are of brick and flint construction. The accommodation has been arranged largely over the ground floor with a magnificent first floor sitting room with the provision for a central wood burner. The attractive ground floor entrance leads down to the large kitchen/dining room with central island, finished in high quality shaker-style units and will have granite work surfaces. There are four bedrooms; three of which have adjoining bath or shower rooms. There is also a cloakroom on the first floor. Outside The property is approached via initially a shared driveway that then sweeps around the neighbouring barn to the private drive to the property where there is ample parking for several vehicles. There is a large farm pole barn and the remaining gardens are largely grassed with mature hedging and trees. The garden in all extends to 0.642 of an acre (est). Situation Fox Barn is situated at the edge of the well served village of Horsford with local facilities including post office, shop, takeaway and public house. Horsford is just under 2 miles from Norwich Airport. Norwich city centre is 5½ miles distant and the nearly completed Northern Distributer Road is just under a mile away, which will link all the major trunk roads out of the city and give ease of access around to the University of East Anglia, Life Science Research Park and hospital. -

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office This list summarises the Norfolk Record Office’s (NRO’s) holdings of parish (Church of England) registers and of transcripts and other copies of them. Parish Registers The NRO holds registers of baptisms, marriages, burials and banns of marriage for most parishes in the Diocese of Norwich (including Suffolk parishes in and near Lowestoft in the deanery of Lothingland) and part of the Diocese of Ely in south-west Norfolk (parishes in the deanery of Fincham and Feltwell). Some Norfolk parish records remain in the churches, especially more recent registers, which may be still in use. In the extreme west of the county, records for parishes in the deanery of Wisbech Lynn Marshland are deposited in the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, whilst Welney parish records are at the Cambridgeshire Record Office. The covering dates of registers in the following list do not conceal any gaps of more than ten years; for the populous urban parishes (such as Great Yarmouth) smaller gaps are indicated. Whenever microfiche or microfilm copies are available they must be used in place of the original registers, some of which are unfit for production. A few parish registers have been digitally photographed and the images are available on computers in the NRO's searchroom. The digital images were produced as a result of partnership projects with other groups and organizations, so we are not able to supply copies of whole registers (either as hard copies or on CD or in any other digital format), although in most cases we have permission to provide printout copies of individual entries. -

Next the Sea: Eccles and the Anthroposcenic

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Nottingham Next the Sea: Eccles and the Anthroposcenic David Matless Accepted for publication in the Journal of Historical Geography, May 2018 Abstract This paper considers the Anthroposcenic, whereby landscape becomes emblematic of processes marking the Anthropocene, through a specific site, Eccles on the northeast coast of Norfolk, England. The coast has become a key landscape for reflections on the Anthropocene, not least through processes of erosion and sea level change; the title phrase ‘next the sea’ here carries both spatial and temporal meaning. Through Eccles the paper investigates cultural-historical Anthropocene signatures over the past two centuries. Between 1862 and 1895 a church tower stood on Eccles beach; in preceding decades the tower was half-buried in sand dunes, but emerged after these were eroded by the sea. In 1895 the tower fell in a storm, although fragments remained intermittently visible over the following century, depending on the state of the beach. The paper takes Eccles tower as a focus for the exploration of themes indicative and/or anticipatory of the Anthropocene, including sea defence and geological speculation on land and sea levels, Eccles featuring in Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology. The tower became a visitor attraction, and discussions around the 1895 fall are examined, in relation to the spectacle of ruin, claims over the site, and anxieties over defence. The periodic beach exposure of bones from the former churchyard prompted reflections on mortality, also present in literary engagements with Eccles by figures such as Henry Rider Haggard. -

Deliverable / Developable Housing Commitments in Broadland 1 April 2017 NPA

Deliverable / Developable Housing Commitments in Broadland 1 April 2017 NPA Net Parish Address Ref Homes 2016/17 Blofield Land off Wyngates 20130296 49 Blofield Land off Blofield Corner Road 20162199 36 Blofield Land East of Plantation Road 20141044 14 Blofield Land Adj. 20 Yarmouth Road 20141710 30 Land South of Yarmouth Road and North Blofield 20150700 73 of Lingwood Road Land South of Yarmouth Road and North Blofield 20150794 30 of Lingwood Road, Phase II Former Piggeries, Manor Farm, Yarmouth Blofield 20150262 13 Road Blofield Land at Yarmouth Road 20160488 175 Vauxhall Mallards & Land Rear of Hillside, Brundall 20141816 21 Strumpshaw Road Drayton Land Adj. Hall Lane 20130885 250 Drayton Land East of School Road DRA 2 20 Land to the North East Side of Church Great and Little Plumstead 20161151 11 Road Great and Little Plumstead Land at Former Little Plumstead Hospital 20160808 109 Hellesdon C T D Tile House, Eversley Road 20152077 65 Land at Hospital Grounds, southwest of Hellesdon HEL1 300 Drayton Road Hellesdon Royal Norwich Golf Course 20151770 1,000 Horsford Land at Sharps Hall Farm 20130547 7 Horsford Land to the East of Holt Road,Horsford 20161770 259 Horsham & Newton St Faiths Land East of Manor Road HNF1 60 Old Catton 11 Dixons Fold 20160257 15 Old Catton Repton House 20151733 7 Salhouse Land Adj. 24 Norwich Road 20141505 2 Thorpe St. Andrew Pinebanks 20160425 231 Thorpe St. Andrew Land at Griffin Lane 20160423 71 Oasis Sport and Leisure Centre, 4 Pound Thorpe St. Andrew 20151132 27 Lane Thorpe St. Andrew 27 Yarmouth Road 20161542 25 Thorpe St. -

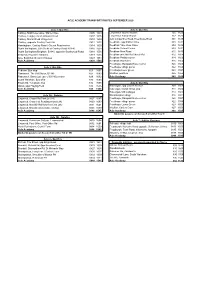

Acle Academy Bus Timetables Sept 2020.Xlsx

ACLE ACADEMY TRANSPORT ROUTES SEPTEMBER 2020 Acle 1: Our Hire Acle 5: Our Hire Cantley, Malthouse Lane / Marie Close 0805 1604 Limpenhoe council houses 755 1625 Cantley, Langley Road, Winsdor Road 0807 1606 Limpenhoe Falcon House 757 1623 Cantley, Manor Road Village Hall 0810 1609 Junc Limpenhoe Road, Freethorpe Road 801 1619 Cantley, opposite Cantley Cock PH 0812 1602 Reedham, opp Station Drive 803 1617 Hassingham, Cantley Road / Church Road corner 0814 1600 Reedham Yare View Close 804 1616 South Burlingham, 50m South of Cantley Road /B1140 0816 1558 Reedham School Corner 809 1611 South Burlingham/Beighton, B1140, opposite Southwood Road 0818 1556 Reedham New Road 810 1610 Beighton, Hopewell Gardens 0819 1555 Reedham junc Mill Rd Church Rd 812 1608 Acle, Beighton rd council houses 0823 1551 Reedham Pettitts corner 814 1606 Acle Academy 0830 1545 Reedham Hall Farm 816 1604 Freethorpe, Rampant Horse corner 820 1600 Acle 2: Our Hire Freethorpe village pump 822 1558 Pedham, Bus stop 823 1607 Freethorpe lower green 823 1557 Panxworth, The Old Stores, B1140 827 1603 Moulton, post box 825 1555 Panxworth, Barns just east of B1140 junction 828 1602 Acle Academy 840 1545 South Walsham, Bus Shltr 830 1600 Pilson Gn, Telephone box 832 1558 Acle 6: Our Hire Upton, Opp Playing Field 835 1555 Halvergate, opp Church Avenue 809 1608 Acle Academy 845 1548 Halvergate Marsh rd bus stop 811 1606 Halvergate Mill Cottages 813 1604 Acle 3A - Dolphin Wickhampton village 816 1601 Lingwood, Chapel Rd/Pack Ln (3A) 0827 1605 Freethorpe, Rampant Horse corner 820