Growing up in Michigan, 1949–1974

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OPUNTIA Books About the Spread of the Human Race Through the Galaxy, Done As Spenglerian History

LET ALL THE NUMBER OF THE STARS GIVE LIGHT by Dale Speirs CITIES IN FLIGHT (1970, hardcover) by James Blish is a omnibus of four OPUNTIA books about the spread of the human race through the galaxy, done as Spenglerian history. The books were written in various lengths between 1950 and 1962, some of which are fix-ups of short stories, and others rearranged for the 1970 omnibus edition, which is the text I review here.. Canada Day 2014 279 I read the series once in the early 1970s as a teenager in rural Red Deer, a second time in the 1980s as a yuppie in Calgary, and for the third and final time as I thin out my library. It made quite an impression on teenaged Dale, now a stranger to me, living as he did in a rural area where nothing ever happened, and Opuntia is published by Dale Speirs, Calgary, Alberta. Since you are reading where all of the kids couldn’t wait until they could escape to the big city. Fifty this only online, my real-mail address doesn’t matter. My eek-mail address (as years later, having spent the majority of my life as a suburban homeowner, my the late Harry Warner Jr liked to call it) is: [email protected] view of the series is not and cannot be the same. When sending me an emailed letter of comment, please include your name and town in the message. Conjures The Wandering Stars. The first book in the omnibus is THEY SHALL HAVE STARS. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1961-08-10

allza Stioofs' Kh-rushchev Sours Celebration· with 'Superbomb' Tnreats or' 6th Title MOSCOW IA'I - Premier Khrusb· his most belligerent in months, he Ibombs are already powerful enough I The reception itself, which fol.\ standing atop the Lenin-stalin I Khrushchev beg a D pleasanU, Iwould permit enough money to be are our principles, but If yon tr7 daev Wednesday night climaxed a tried to temper it by repeatedly to . wipe out most cities at one lowed a massive. parade through tomb, IM;gan with a str~ orebes- with remarks about Titov', flight diverted to helping UDderdeveloped to frighten us -" bUoyant day celebrating the Soviet milcing his warnings with this strike. Red Square reV1e\lfed by Tltov Ira playmg as guests arrived. and the hope that disannameDI nations. At this point he dropped the sen I AAU Meet Union's power in outer space with phrase: "We do not want war." , "4 f "" "' " ".. " Then he began to warm up. He tence and continued: "They triet • grim boast that Soviet scientists "r don't want to cast a shadow It said that Western threats would to frighten Lenin and failed. De ULADELPHIA !A'I - ~ (Ill make a bOmb far bigger tban on today with such grim reality," DOt prevent the Soviet Union from they think they can frighten us "" £inest woman swimmer, ~ anY ever built before. he said. But this was exacUy what signing a peace treaty with East fnrty years later in ligbt of all out I·to·retire Chris von SaIIta, ~ He warned that he would give happened. Diplomats gatbered in Germany, thus giving the Eatt strength?" It for an unprecedented liz bis scientists the signal to build corners to translate the words German regime control over west· In an apparent challenge to the s as she leads the Santa CII!1 it if prospects (or peace do not among themselves and read them em access rights to Berlin. -

Central Skagit Rural Partial County Library District Regular Board Meeting Agenda April 15, 2021 7:00 P.M

DocuSign Envelope ID: 533650C8-034C-420C-9465-10DDB23A06F3 Central Skagit Rural Partial County Library District Regular Board Meeting Agenda April 15, 2021 7:00 p.m. Via Zoom Meeting Platform 1. Call to Order 2. Public Comment 3. Approval of Agenda 4. Consent Agenda Items Approval of March 18, 2021 Regular Meeting Minutes Approval of March 2021 Payroll in the amount of $38,975.80 Approval of March 2021 Vouchers in the amount of $76,398.04 Treasury Reports for March 2021 Balance Sheet for March 2021 (if available) Deletion List – 5116 Items 5. Conflict of Interest 5. Communications 6. Director’s Report 7. Unfinished Business A. Library Opening Update B. Art Policy (N or D) 8. New Business A. Meeting Room Policy (N) B. Election of Officers 9. Other Business 10. Adjournment There may be an Executive Session at any time during the meeting or following the regular meeting. DocuSign Envelope ID: 533650C8-034C-420C-9465-10DDB23A06F3 Legend: E = Explore Topic N = Narrow Options D = Decision Information = Informational items and updates on projects Parking Lot = Items tabled for a later discussion Current Parking Lot Items: 1. Grand Opening Trustee Lead 2. New Library Public Use Room Naming Jeanne Williams is inviting you to a scheduled Zoom meeting. Topic: Board Meeting Time: Mar 18, 2021 07:00 PM Pacific Time (US and Canada) Every month on the Third Thu, until Jan 20, 2022, 11 occurrence(s) Mar 18, 2021 07:00 PM Apr 15, 2021 07:00 PM May 20, 2021 07:00 PM Jun 17, 2021 07:00 PM Jul 15, 2021 07:00 PM Aug 19, 2021 07:00 PM Sep 16, 2021 07:00 PM Oct 21, 2021 07:00 PM Nov 18, 2021 07:00 PM Dec 16, 2021 07:00 PM Jan 20, 2022 07:00 PM Please download and import the following iCalendar (.ics) files to your calendar system. -

Fiction) Anderson, Kevin J

Abbott, Karen Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy Abe, Shana Queen of Dragons Abe, Shana The Dream Thief Abe, Shana The Smoke Thief Achebe, Chinua Things Fall Apart Adams, Doug The Restaurant at the End of the Universe Adams, Richard Watership Down Adcock, Thomas Dark Maze Adler, Elizabeth The Property of a Lady Ahern, Cecelia If you could See Me Now Akst, Daniel St. Burl's Obituary Albee, Edward Who's Afraid of Virginia Wolf Albom, Mitch For One More Day Albom, Mitch The Five People You Meet in Heaven (2) Albom, Mitch The Time Keeper Alcott, Louisa May Little Women (One In House) (2) Alexander, Bruce Blind Justice Alison, Jane The Love Artist Allen, Dwight Judge Allende, Isabel Daughter of Fortune Allende, Isabel Portrait in Sepia Allende, Isabel Zorro Allison, Dorothy Bastard out of Carolina Alvarez, Julia How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents Amory, Cleveland The Cat and the Curmudgeon Amory, Cleveland The Cat Who Came for Christmas Anaya, Rudolfo Bless Me, Ultima Anderson, Catherine Comanche Magic Anderson, Catherine Comanche Moon Anderson, Catherine Morning Light Anderson, Kent Night Dogs Anderson, Kevin J. Hidden Empire (Sci Fi) Anderson, Kevin & Doug Beason Lethal Exposure (Sci Fi) Anderson, Kevin J. Of Fire and Night (Science Fiction) Anderson, Kevin J. Scattered Suns (Science Fiction) Anderson, Susan Baby Don't Go Andreas, Steve Is There Life Before Death? Anderson, Susan Getting Lucky Andrews, Mary Kay Blue Christmas (large print) Andrews, V.C. Delia's Crossing Ansay, A. Manette Vinegar Hill Archer, Jeffrey A Matter of Honor Archer, -

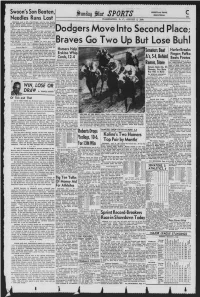

Dodgers Move Into Second Place; Braves Go Two up but Lose Buhl

Swoon's Son Beaten, RESORTS and TRAVEL C Sunday J&faf SPORTS EDUCATIONAL Needles Runs Last WASHINGTON, D. C., AUGUST 5, 1956 CHICAGO, Aug. 4 UP).— Two ! Chicago, won by four lengths of the Nation’s top thorough- over Swoon’s Son in the one-mile breds suffered defeats under a Sheridan for 3-year-olds. Ridden broiling sun at Washington Park by Willie Shoemaker, Ben A. today. Jones returned $16.20, $3.60 and Swoon’s Son was whipped by $2.80. Ben A. Jones in the featured Swoon's Son, previously un- year, Dodgers $27,475 Sheridan Handicap, and beaten in five races this Move Place; Needles, Into Second the Kentucky Derby and went off the l-to-2 favorite. He Belmont Stakes winner was was coupled in the betting with eighth and last in an overnight Dark Toga, who finished third. handicap on the grass in which Fabius, the Winner, a new American six-furlong turf ran fourth. mark was set. Ridden by Dave Erb, who Burnt Child, a 5-year-old, won piloted him in the Derby and the six-furlong event with a Up W’as Braves Belmont, Neddies last out of Go Two But Lose Buhl the gate and the six-furlong dis- Picture on Page C-6 tance proved far too short for his famed stretch drive. record clocking or 1:09 4£ and Needles set sail after the pace- Homers Help Hurler Breaks paid $64.60 to win. Needles, mak- setter, Suthern Accent, and fast- Senators Beat ing his first start against older closing Burnt Child down the Whip horses and his debut on the stretch, but he just reached the Erskine Finger; Pafko grass, was using the race as a rear of the pack when the race prep for the SIOO,OOO-added was over. -

A. Arnold the Erotics of Colonialism in Contemporary French West Indian

A. Arnold The erotics of colonialism in contemporary French West Indian literary culture Argues that creolité, antillanité and Negritude are not only masculine but masculinist as well. They permit only male talents to emerge within these movements and push literature written by women into the background. Concludes that in the French Caribbean there are 2 literary cultures: the one practiced by male creolistes and the other practiced by a disparate group of women writers. In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 68 (1994), no: 1/2, Leiden, 5-22 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl A. JAMES ARNOLD THE EROTICS OF COLONIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY FRENCH WEST INDIAN LITERARY CULTURE The créolité movement has inherited from its antecedents, antillanité and Negritude, a sharply gendered identity. Like them, it is not only masculine but masculinist. Like them, it permits only male talents to emerge within the movement, to carry its seal of approval. And, like them, it pushes literature written by women into the background. This characteristic is not, however, unique to the French West Indies. It can be found, mutatis mutandis, across the Caribbean archipelago with its variations on the "repeating island," in Antonio Benitez-Rojo's (1992:1-29) felicitous expression. In a word, créo- lité is the latest avatar of the masculinist culture of the French West Indies, which is being steadily challenged by the more recently emerged, less theo- retically articulated, womanist culture, to borrow a term from the Anglo- phone West Indies. These two sharply gendered cultural visions are cur- rently in a state of competition and struggle. -

OWNER-RATED CARS! I.D a 6.00X16 J 11.38 100% Cold Ruhh.R V*W Tr««D« 'S Only Logan Gives You a Signed Statement from '^ Wmtwak «M*.S T.Ipxis the Former Owner

• THE EVENING STAR, Washington, D. C. combe said, and he looked It. Surgery --- TMUaSDAT. JUNE 37. for mmsm ItSl Umpire - C-4 , “Those were real tape-measure jy p - —m—Lr —l_ ALLENTOWN. Pa.. June 27 . MAJOR (/t) 39-year-old Jobs.” LEAGUE BOX SCORES —Jim Honochick, ! Where do Jaycees MILLER FIELDS BUICK American League umpire, may the fit ln? Well, they're staging a cam- Tfte area's newest Buick dealer Busby Says YANKS, 3; INDIANS, 1 PIRATES, 15-5; CUBS, 5-5 WHITE SOX, 7; RED SOX, be operated on today for a kid- New Power 5 paign ney to elect a president and Cleveland. A.H.O.A. New Verb. A.H.O.A. FIRST OAME ('hirst# A.H.O.A. Boot** A.H.O.A. ailment. He was stricken they’re doing it Smith.3b 4 10 1 Rl'dson,2b Slid 1 Pittsburgh A.H.O.A. Chieagu AHOA Aparlclo.ss 4 o 5 4 piersall.cf 4 () 4 (I at beginning of 1 around and in Raines.2b A 1 2 4 McD Id.is 4 0 2 1 I Maz'aki.'.’b 8 2 15 Morgan.2b 3 o o 1 Fox,2b 512 3 Klaus.ss 53 1 the the Cleve- the hotel 1 . 2 5 downtown where the Swing Werti,lb 3210 0 Mantle.cl 32 4 0) Vlrdon,cf 5 2 2 (> Wise.2b 101 I l Mtnoso.lf 4 1 4 Ii Williams.lf 3 110 I land-New York game ln Yankee Is to .VWilliam on Collins, lb 2 ofl o• IPen'on.rf 1 0 0 u 4Bolger 1 n 0 0 Doby.cf 3 3 1 (I Vernon,lb Dodgers are staying. -

Kindle Unlimited Mystery Crime Fiction Page 1 Last

Kindle Unlimited Mystery Crime Fiction Last First Series/Title Genre Setting Comment* Allingham Margery Albert Campion series – The Fashion in Shrouds 1930s classic police procedural England Armstrong Charlotte Various, A Dram of Poison Classic 1950s American suspense, humor Various Atwood Russell Payton Sherwood series – East of A, Losers Live Longer Contemporary, PI East Village Various series and many standalone: Dan Starkey series – Contemporary, PI, humorous; unnamed neurotic Divorcing Jack; Man with No Name series – Mystery Man The bookstore owner, amateur sleuth; disgraced Bateman Colin Case of the Jack Russell; standalone – Cycle of Violence reporter Belfast; Northern Ireland S Pseudonym of Susannah Gregory. Sir Geoffrey Mappestone Beaufort Simon series – Deadly Inheritance (earlier books are not available) Knight during the Crusades Wales Beinhart Larry Tony Cassella series – No One Rides for Free Contemporary wise-cracking PI New York Bernhardt William Various, Ben Kincaid series – Primary Justice Contemporary legal thrillers Tulsa, OK Bishop Paul Various, Det. Faye Croaker series – Kill Me Again Contemporary, police procedural Los Angeles R Blevins Meredith Mystic Cafe/Annie Szabo series – The Hummingbird Wizard Contemporary, gypsies, humorous California S Block Lawrence Various, but not his series work Bowen Peter Gabriel Du Pré series – Coyote Wind Cattle inspector, amateur sleuth Montana Brand Christianna Three classic British police series – Green for Danger WWII England Breslin Jimmy Various – The Gang That Couldn't Shoot Straight Contemporary, mobsters New York City Quint McCauley series – Murder in Store, Error in Judgment; Contemporary, ex-cop, head of security, PI; Brod D. C. Robyn Guthrie series – Getting Sassy, Getting Lucky freelance writer, caper Chicago area Various, Roberts & Brant – The White Trilogy; standalone – Bruen Ken Her Last Call to Louis MacNiece Contemporary, noir, violent London R Buchan John Various, Richard Hannay series – The Thirty-Nine Steps Classic WWI spy thriller England Cain James M. -

Dec 11 Cover.Qxd 11/5/2020 2:39 PM Page 1 Allall Starstar Cardscards Volumevolume 2828 Issueissue #5#5

ASC080120_001_Dec 11 cover.qxd 11/5/2020 2:39 PM Page 1 AllAll StarStar CardsCards VolumeVolume 2828 IssueIssue #5#5 We are BUYING! See Page 92 for details Don’t Miss “CyberMonday” Nov. 30th!!! It’s Our Biggest Sale of theYear! (See page 7) ASC080120_001_Dec 11 cover.qxd 11/5/2020 2:39 PM Page 2 15074 Antioch Road To Order Call (800) 932-3667 Page 2 Overland Park, KS 66221 Mickey Mantle Sandy Koufax Sandy Koufax Willie Mays 1965 Topps “Clutch Home Run” #134 1955 Topps RC #123 Centered! 1955 Topps RC #123 Hot Card! 1960 Topps #200 PSA “Mint 9” $599.95 PSA “NM/MT 8” $14,999.95 PSA “NM 7” $4,999.95 PSA “NM/MT 8” Tough! $1,250.00 Lou Gehrig Mike Trout Mickey Mantle Mickey Mantle Ban Johnson Mickey Mantle 1933 DeLong #7 2009 Bowman Chrome 1952 Bowman #101 1968 Topps #280 1904 Fan Craze 1953 Bowman #59 PSA 1 $2,499.95 Rare! Auto. BGS 9 $12,500.00 PSA “Good 2” $1,999.95 PSA 8 $1,499.95 PSA 8 $899.95 PSA “VG/EX 4” $1,799.95 Johnny Bench Willie Mays Tom Brady Roger Maris Michael Jordan Willie Mays 1978 Topps #700 1962 Topps #300 2000 Skybox Impact RC 1958 Topps RC #47 ‘97-98 Ultra Star Power 1966 Topps #1 PSA 10 Low Pop! $999.95 PSA “NM 7” $999.95 Autographed $1,399.95 SGC “NM 7” $699.95 PSA 10 Tough! $599.95 PSA “NM 7” $850.00 Mike Trout Hank Aaron Hank Aaron DeShaun Watson Willie Mays Gary Carter 2011 Bowman RC #101 1954 Topps RC #128 1964 Topps #300 2017 Panini Prizm RC 1952 Bowman #218 1981 Topps #660 PSA 10 - Call PSA “VG/EX 4” $3,999.95 PSA “NM/MT 8” $875.00 PSA 10 $599.95 PSA 3MK $399.95 PSA 10 $325.00 Tough! ASC080120_001_Dec 11 cover.qxd -

Price 1 $45,000.00 2 $15,500.00 3 $32,000.00 4

Lot # Description Price 1 Complete Set of (33) 1954 Red Heart Baseball all PSA Graded $45,000.00 2 1911 T3 Turkey Red Ty Cobb Cabinet-Checklist Back PSA 5 EX $15,500.00 3 1933 Delong #7 Lou Gehrig SGC 88 NM/MT 8 $32,000.00 4 1932 U.S. Caramel #26 Lou Gehrig SGC 88 NM/MT 8 $21,000.00 5 1932 U.S. Caramel #32 Babe Ruth SGC 86 NM+ 7.5 $25,000.00 6 1956 World Champion New York Yankees Team Signed Baseball with 24 Signatures PSA/DNA LOA $4,500.00 7 1954 New York Giants Signed Baseball with 29 Signatures including HOF'ers Willie Mays, Leo Durocher, & Monte Irvin PSA/DNA$4,500.00 LOA 8 1911 T205 Gold Border Cy Young PSA 8 NM-MT $19,995.00 9 1907-09 Novelty Cutlery/Postcard Ty Cobb/H. Wagner PSA 6 EX-MT $17,500.00 10 Babe Ruth Dual Signed Check PSA/DNA AUTHENTIC $5,500.00 11 Babe Ruth Single Signed Check PSA/DNA 8 NM-MT $4,950.00 12 1921-1931 Babe Ruth H&B Game Used Professional Model Bat Mears LOA $20,000.00 13 1933 Goudey #53 Babe Ruth SGC 86 NM+ 7.5 $26,000.00 14 1930 Roger's Peet #48 Babe Ruth PSA 5 EX $4,495.00 15 1909-11 T206 Piedmont Ty Cobb Portrait, Green Background SGC 86 NM+ 7.5 $30,000.00 16 1909-11 T206 Piedmont Ty Cobb Portrait, Green Background 350 Subjects Factory #25 SGC 60 EX 5 $4,500.00 17 1910 T213 Coupon Cigarette Ty Cobb SGC 50 VG/EX 4 $4,000.00 18 1912 T202 Hassan Triple Folder T.Cobb/C.O'Leary Fast Work at Third PSA 8 NM-MT $10,995.00 19 1911 T205 Gold Border Ty Cobb PSA 7 NM $15,000.00 20 1909-11 T206 Sweet Caporal Ty Cobb Portrait, Red Background 350 Subjects Factory #30 SGC 84 NM 7 $4,895.00 21 1909-11 T206 Sweet Caporal -

The Rugs of Nero Wolfe Et Al

―Huh?‖ ―Shut up,‖ he hissed, and he meant it. 2011 GAZETTE WRITING CONTEST WINNER Taking his handkerchief, he started moving slowly through the room. As far as I could see, nothing was wrong. The Rugs of Nero Wolfe Et Al. Then I saw Harold. Stephen C. Jett1 He was sitting in his chair, as always, with a copy of Shakespeare's son- THE BROWNSTONE ON WEST 35th STREET nets on his lap, the same way I had seen him a thousand times. He was- n‘t reading, however, nor would he ever read anything again. Blood had ccording to Rex Stout‘s novels, detective Nero Wolfe owns and dripped down to the pages, landing on the phrase ―Lilies that fester lives in an old brownstone house located between 10th and 11th smell far worse than weeds.‖ Avenues on the south side of West 35th Street, Manhattan, New A York City (the number is variously given as 618, 902, 909, 914, 918, Living in the Village for some years, I had seen a lot of odd things, but 922, 924, and 938). Nero Wolfe is a man of refined tastes in many they were more like Neal Cassady hanging naked from a chandelier things, including cuisine, Orchidae, books, and comfortable furnishings. singing ―Mairzy Doats.‖ This one struck me speechless. The last category includes Oriental rugs. Others before me have tackled the question as to what kinds of rugs Wolfe and his assistant Archie Not Goodwin. He turned on me, angrily. ―Is this your idea of being Goodwin have possessed (Baring-Gould 1970:41; Gotwald 1993:175-78; cute?‖ he snapped. -

1957 Topps Baseball Checklist

1957 Topps Baseball Checklist 1 Ted Williams 2 Yogi Berra 3 Dale Long 4 Johnny Logan 5 Sal Maglie 6 Hector Lopez 7 Luis Aparicio 8 Don Mossi 9 Johnny Temple 10 Willie Mays 11 George Zuverink 12 Dick Groat 13 Wally Burnette 14 Bob Nieman 15 Robin Roberts 16 Walt Moryn 17 Billy Gardner 18 Don Drysdale 19 Bob Wilson 20 Hank Aaron 21 Frank Sullivan 22 Jerry Snyder 23 Sherm Lollar 24 Bill Mazeroski 25 Whitey Ford 26 Bob Boyd 27 Ted Kazanski 28 Gene Conley 29 Whitey Herzog 30 Pee Wee Reese 31 Ron Northey 32 Hersh Free Hershell Freeman on Card 33 Jim Small 34 Tom Sturdivant 35 Frank Robinson 36 Bob Grim 37 Frank Torre 38 Nellie Fox 39 Al Worthington 40 Early Wynn 41 Hal Smith Hal W. Smith on Card 42 Dee Fondy 43 Connie Johnson 44 Joe DeMaestri Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 45 Carl Furillo 46 Bob Miller Robert J. Miller on Card 47 Don Blasingame 48 Bill Bruton 49 Daryl Spencer 50 Herb Score 51 Clint Courtney 52 Lee Walls 53 Clem Labine 54 Elmer Valo 55 Ernie Banks 56 Dave Sisler 57 Jim Lemon 58 Ruben Gomez 59 Dick Williams 60 Billy Hoeft 61 Dusty Rhodes 62 Billy Martin 63 Ike Delock 64 Pete Runnels 65 Wally Moon 66 Brooks Lawrence 67 Chico Carrasquel 68 Ray Crone 69 Roy McMillan 70 Richie Ashburn 71 Murry Dickson 72 Bill Tuttle 73 George Crowe 74 Vito Valentinetti 75 Jimmy Piersall 76 Roberto Clemente 77 Paul Foytack 78 Vic Wertz 79 Lindy McDaniel 80 Gil Hodges 81 Herm Weh Herman Wehmeier on Card 82 Elston Howard 83 Lou Skizas 84 Moe Drabowsky 85 Larry Doby 86 Bill Sarni 87 Tom Gorman 88 Harvey Kuenn 89 Roy Sievers 90 Warren Spahn 91 Mack Burk Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 2 92 Mickey Vernon 93 Hal Jeffcoat 94 Bobby Del Greco 95 Mickey Mantle 96 Hank Aguirre 97 Yankees Team Card 98 Alvin Dark 99 Bob Keegan 100 W.