Mancini, Antonio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mancini, Antonio

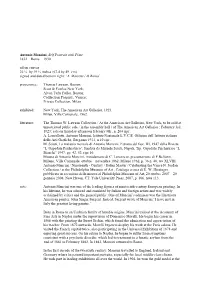

Antonio Mancini, Self Portrait with Plate 1852 – Rome – 1930 oil on canvas 26 ½ by 19 ¼ inches (67.4 by 49 cm) signed and dated bottom right: ‘A. Mancini / di Roma’ provenance: Thomas Lawson, Boston; Scott & Fowles New York; Alvan Tufts Fuller, Boston; Colllection Pospisil , Venice; Private Collection, Milan exhibited: New York, The American Art Galleries, 1923. Milan, Villa Comunale, 1962. literature: The Thomas W. Lawson Collection / At the American Art Galleries, New York, to be sold at unrestricted public sale / in the assembly hall / of The American Art Galleries ; February 3rd, 1923; sale on thursday afternoon february 8th., n. 204 ripr.. A. Lancellotti, Antonio Mancini, Istituto Nazionale L.V.C.E. Officine dell’Istituto italiano delle Arti Grafiche, Bergamo 1931, n.10 ripr.. M. Sciuti, La malattia mentale di Antonio Mancini, Estratto del fasc. III, 1947 della Rivista “L’Ospedale Psichiatrico”, fondata da Michele Sciuti, Napoli, Tip. Ospedale Psichiatrico “L. Bianchi” 1947, pp. 42, 52, ripr 16. Mostra di Antonio Mancini, introduzione di C. Lorenzetti, presentazione di F.Bellonzi, Milano, Villa Comunale, ottobre – novembre 1962, Milano 1962, p. 36 n. 48, tav XLVIII. Antonio Mancini / Nineteenth - Century / Italian Master / Celebrating the Vance N. Jordan Collection / at the Philadelphia Museum of Art , Catalogo a cura di U. W. Hiesinger, pubblicato in occasione della mostra al Philadelphia Museum of Art, 20 ottobre 2007 – 20 gennaio 2008, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007, p. 106, nota 113. note: Antonio Mancini was one of the leading figures of nineteenth-century European painting. In his lifetime, he was admired and emulated by Italian and foreign artists and was widely acclaimed by critics and the general public. -

NGA | 2017 Annual Report

N A TIO NAL G ALL E R Y O F A R T 2017 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Board of Trustees COMMITTEE Buffy Cafritz (as of September 30, 2017) Frederick W. Beinecke Calvin Cafritz Chairman Leo A. Daly III Earl A. Powell III Louisa Duemling Mitchell P. Rales Aaron Fleischman Sharon P. Rockefeller Juliet C. Folger David M. Rubenstein Marina Kellen French Andrew M. Saul Whitney Ganz Sarah M. Gewirz FINANCE COMMITTEE Lenore Greenberg Mitchell P. Rales Rose Ellen Greene Chairman Andrew S. Gundlach Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary of the Treasury Jane M. Hamilton Richard C. Hedreen Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Helen Lee Henderson Chairman President David M. Rubenstein Kasper Andrew M. Saul Mark J. Kington Kyle J. Krause David W. Laughlin AUDIT COMMITTEE Reid V. MacDonald Andrew M. Saul Chairman Jacqueline B. Mars Frederick W. Beinecke Robert B. Menschel Mitchell P. Rales Constance J. Milstein Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Pappajohn Sally Engelhard Pingree David M. Rubenstein Mitchell P. Rales David M. Rubenstein Tony Podesta William A. Prezant TRUSTEES EMERITI Diana C. Prince Julian Ganz, Jr. Robert M. Rosenthal Alexander M. Laughlin Hilary Geary Ross David O. Maxwell Roger W. Sant Victoria P. Sant B. Francis Saul II John Wilmerding Thomas A. Saunders III Fern M. Schad EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Leonard L. Silverstein Frederick W. Beinecke Albert H. Small President Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Michelle Smith Chief Justice of the Earl A. Powell III United States Director Benjamin F. Stapleton III Franklin Kelly Luther M. -

Vincenzo Gemito (1852-1929) October 2019 Sculptor of the Neapolitan Soul from 15 October 2019 to 26 January 2020

PRESS KIT Vincenzo Gemito (1852-1929) October 2019 Sculptor of the Neapolitan soul from 15 October 2019 to 26 January 2020 Tuesday to Sunday 10am to 6pm INFORMATIONS Late opening Friday until 9pm www.petitpalais.paris.fr . Museo e Certosa di San Martino, Photo STUDIO SPERANZA STUDIO Photo Head of a young boy Naples. Fototeca del polo museale della campaniaNaples. Fototeca Vincenzo Gemito, PRESS OFFICER : Mathilde Beaujard [email protected] / + 33 1 53 43 40 14 Exposition organised in With the support of : collaboration with : Vincenzo Gemito (1852-1929), Sculptor of the Neapolitan soul- from 15 October 2019 to 26 January 2020 SOMMAIRE Press release p. 3 Guide to the exhibition p. 5 The Exhibition catalogue p. 11 The Museum and Royal Park of Capodimonte p. 12 Paris Musées, a network of Paris museums p. 19 About the Petit Palais p. 20 Practical information p. 21 2 Vincenzo Gemito (1852-1929), Sculptor of the Neapolitan soul- from 15 October 2019 to 26 January 2020 PRESS RELEASE At the opening of our Neapolitan season, the Petit Pa- lais is pleased to present work by sculptor Vincenzo Gemito (1852-1929) that has never been seen in France. Gemito started life abandoned on the steps of an or- phanage in Naples. He grew up to become one of the greatest sculptors of his era, celebrated in his home- town and later in the rest of Italy and Europe. At the age of twenty-five, he was a sensation at the Salon in Paris and, the following year, at the 1878 Universal Ex- position. -

ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 3: ISSN 2640-8511 Introduction

ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 3: ISSN 2640-8511 Introduction ITALIAN MODERN ART - ISSUE 3 | INTRODUCTION italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/introduction-3 Raffaele Bedarida | Silvia Bignami | Davide Colombo Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), Issue 3, January 2020 https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/methodologies-of- exchange-momas-twentieth-century-italian-art-1949/ ABSTRACT A brief overview of the third issue of Italian Modern Art dedicated to the MoMA 1949 exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art, including a literature review, methodological framework, and acknowledgments. If the study of artistic exchange across national boundaries has grown exponentially over the past decade as art historians have interrogated historical patterns, cultural dynamics, and the historical consequences of globalization, within such study the exchange between Italy and the United States in the twentieth-century has emerged as an exemplary case.1 A major reason for this is the history of significant migration from the former to the latter, contributing to the establishment of transatlantic networks and avenues for cultural exchange. Waves of migration due to economic necessity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries gave way to the smaller in size but culturally impactful arrival in the U.S. of exiled Jews and political dissidents who left Fascist Italy during Benito Mussolini’s regime. In reverse, the presence in Italy of Americans – often participants in the Grand Tour or, in the 1950s, the so-called “Roman Holiday” phenomenon – helped to making Italian art, past and present, an important component in the formation of American artists and intellectuals.2 This history of exchange between Italy and the U.S. -

Ontdek Schilder, Pastellist, Tekenaar Antonio Mancini

52247 Antonio Mancini man / Italiaans schilder, pastellist, tekenaar Kwalificaties schilder, pastellist, tekenaar Nationaliteit/school Italiaans Geboren Albano Laziale/Rome 1852-11-14 Bénézit, Hiesinger, Thieme/Becker and Vollmer: Rome. Saur-index: Rome or Albano Laziale Overleden Rome 1930-12-28 Deze persoon/entiteit in andere databases 53 treffers in RKDimages als kunstenaar 12 treffers in RKDlibrary als onderwerp Verder zoeken in RKDartists& Geboren 1852-11-14 Sterfplaats Rome Plaats van werkzaamheid Napels Plaats van werkzaamheid Venetië Plaats van werkzaamheid Ischia, Isola d' (eiland) Plaats van werkzaamheid Milaan Plaats van werkzaamheid Parijs Plaats van werkzaamheid Rome Plaats van werkzaamheid Londen (Engeland) Plaats van werkzaamheid Dublin Plaats van werkzaamheid Terracina Plaats van werkzaamheid München Plaats van werkzaamheid Berlijn Plaats van werkzaamheid Neurenberg Plaats van werkzaamheid Keulen Plaats van werkzaamheid Nederland Plaats van werkzaamheid Frascati Plaats van werkzaamheid Minori (Italië) Plaats van werkzaamheid Formia Kwalificaties schilder Kwalificaties pastellist Kwalificaties tekenaar Onderwerpen figuurvoorstelling Onderwerpen genrevoorstelling Onderwerpen landschap (als genre) Onderwerpen naaktfiguur Onderwerpen portret Onderwerpen kinderportret Onderwerpen zelfportret Onderwerpen christelijk religieuze voorstelling Onderwerpen strandgezicht Opleiding Istituto di Belle Arti di Napoli Standplaats archief archief Firma E.J. van Wisselingh & Co. Standplaats archief archief Kees Maks Biografische gegevens -

Callisto Fine Arts

CALLISTO FINE ARTS 17 Georgian House 10 Bury Street London SW1Y 6AA +44 (0)207 8397037 [email protected] www.callistoart.com Antonio Mancini (Rome, 1852-1930) Portrait of woman Pastel on paper applied on canvas, 75 x 60 cm Signed on the top left corner: A Mancini Exhibitions: Galleria Milano, Arte Moderna, Milano 1932, n. 4395 (label on the back) The work is archived in the Archive and Catalogue of Paintings by Antonio Mancini, with n. 56(1)0220 AV Our elegant Portrait of a Lady is one of the marvellous large pastels applied on canvas made by Antonio Mancini at the apex of his career as portraitist. The technique closely resembles that of his well-known oil paintings, revealing the mellowness of the medium chosen by the artist and a sapient use of colours – in our Portrait, an ochre-black palette, lightened up by the luminous whites and the few colourful details in the woman’s dress and make-up. White is also used by Mancini to draw the essential elements of the room CALLISTO FINE ARTS 17 Georgian House 10 Bury Street London SW1Y 6AA +44 (0)207 8397037 [email protected] www.callistoart.com in which the lady, wearing festive clothes in the Belle Époque fashion, is sitting gazing at the painter. The beholder perceives the portrait as particularly ephemeral because of the pastel technique which is characterised by swift and unruly touches. However, Mancini manages to imprison the essence of his model. Her talking eyes, half-closed lips and her fiddling with her fur, indeed, reveal an intimacy which was probably evident to those who knew the beautiful woman, and which still creates a strong bond with those admiring her nowadays. -

6F0e350f7233ac7a561ed2c5099

sovracoperta Enrico.pdf 1 11/10/16 15:03 193767_TIL_Volume_Mancini.indd 1 11/10/16 11:33 Il Piccolo Savoiardo Storia ed Analisi di un Capolavoro a cura di Cinzia Virno 193767_TIL_Volume_Mancini.indd 2 11/10/16 11:33 Il Piccolo Savoiardo Storia ed Analisi di un Capolavoro a cura di Cinzia Virno 193767_TIL_Volume_Mancini.indd 3 11/10/16 11:33 ANTONIO MANCINI (1852 – 1930) Il Piccolo Savoiardo Storia ed Analisi di un Capolavoro 20 Ottobre – 18 Dicembre 2016 Via Senato, 45 – Milano Progetto espositivo / Exhibition design Referenze fotografche / Photos Angelo Enrico Archivio Mancini - Studio Cinzia Virno, Roma Galleria Enrico, Milano Catalogo a cura di / Catalogue edited by Gallerie Maspes, Milano Cinzia Virno Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles Studio Fotograco erotti, Milano Traduzione / Translation Arkadia Translations, Milano Un ringraziamento particolare a Francesco Luigi Maspes ed Elisabetta Staudacher, per la collaborazione e la disponibilità Progetto grafco / Graphic design project nel fornire documentazione d’archivio della Collezione Rossello. Ales Bonaccorsi A special thank to Francesco Luigi Maspes and Elisabetta Staudacher for their collaboration and willingness to provide documentation Assicurazioni / Insurance on Rossello Collection. Ciaccio Borker, Milano Si ringrazia inoltre / Thanks also to Distribuzione libraria / Book distribution Eredi Rossello, Dunia Grandi, aul Nicholls, Antiga Edizioni Chiara revosti, Stella Seitun ISBN 978-88-99657-47-5 © 2016 Antiga Edizioni © 2016 ENRICO • GALLERIE D’ARTE MILANO • Via Senato, 45 -

Another History: Contemporary Italian Art in America Before 1949

ISSN 2640-8511 ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 3: Another History: Contemporary Italian Art in America Before 1949 ANOTHER HISTORY: CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN AMERICA BEFORE 1949 0 italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/another-history-contemporary-italian-art-in- Sergio Cortesini Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth- Century Italian Art” (1949), Issue 3, January 2020 ABSTRACT This essay looks at modern Italian art circulating in the United States in the interwar period. Prior to the canonization of recent decades of Italy’s artistic scene through MoMA’s 1949 show Twentieth-Century Italian Art, the Carnegie International exhibitions of paintings in Pittsburgh were the premier stage in America for Italian artists seeking the spotlight. Moreover, the Italian government actively sought to promote its own positive image as a patron state in world fairs, and through art gallery exhibitions. Drawing mostly on primary sources, this essay explores how the identity of modern Italian art was negotiated in the critical discourses and in the interplay between Italian and American promoters. While in Italy much of the criticism boasted a self-assuring “untranslatable” character of national art through the centuries, and was obsessed by the chauvinistic ambition of regaining cultural primacy, especially against the French, the returns for those various artists and patrons who ventured to conquer the American art scene were meager. Rather than successfully affirming the modern Italian school, they remained largely entangled in a shadow zone, between -

Download PDF Version

Jean-Luc Baroni Lucian Freud: A Walk to the Office (no. 55 ), actual size JEAN-LUC BARONI PAINTINGS SCULPTURES DRAWINGS 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am very grateful to Alexandra Chaldecott and Joanna Watson for their dedication in researching and writing this catalogue. Christopher Apostle, Francesca Baldassari, Jean-Marc Baroni, my son Pietro Baroni, Antonio Berni, Giuseppe Bertini, Anna Bozena Kowalczyk, Christina Buley-Uribe, Suzanna Caviglia, Hugo Chapman, Martin Clayton, Pierre Etienne, Chris Fischer, Saverio Fontini, Daniel Greiner, Neil Jeffares, Paul Joannides, Mattia Jona, Annemarie Jordan Gschwend, Neil Jeffares, William Jordan, Francesco Leone, Laurie and Emmanuel Marty de Cambiaire, Laetitia Masson, Alessandro Morandotti, Ekaterina Orekhova, Anna Ottani Cavina, Francesco Petrucci, Anna Reynolds, Aileen Ribeiro, Jane Roberts, Clare Robertson, Cristiana Romalli, Annalisa Scarpa, Paul Taylor and the Warburg Institute, Cinzia Virno, Emanuele Volpi, Joanna Woodall, Selina Woodruff-Van der Geest, Tiziana Zennaro. Last but not least, I am also very grateful to my wife Cristina for her unrelenting patience and for her continued help and support. Jean-Luc Baroni All enquiries should be addressed to Jean-Luc Baroni at Jean-Luc Baroni Ltd., 7/8 Mason’s Yard, Duke Street, St. James’s, London, SW1Y 6BU. Tel: +44 (20) 7930-5347 e-mail: [email protected] © Copyright Jean-Luc Baroni Ltd., 2014 Designed by Saverio Fontini - Printed in Italy by Viol’Art – Florence – email: [email protected] renze.it 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am very grateful to Alexandra -

Pier Francesco Mola Coldrerio, Ticino 1612 - 1666 Rome

JEAN-LUC BARONI Paintings Drawings Sculptures Rosalba Carriera, no. 7 (detail) JEAN-LUC BARONI Paintings Drawings Sculptures 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am very grateful to Alexandra Chaldecott and Joanna Watson for their dedication in researching and writing the catalogue, and Saverio Fontini of Viol’Art for his valuable assistance and his creatively designed catalogue. I would also like to thank the following people for their help and advice in the preparation of this catalogue: My brother Jean-Marc, my sons Matteo and Pietro, Fabio Benzi, Donatella Biagi Maino, Marco Simone Bolzoni, Maria Teresa Caracciolo, Bruno Chenique, Keith Christiansen, Jean-Pierre Cuzin, Pierre Etienne, Marco Fagioli, Catherine Monbeig Goguel, Philippe Grunchec, Bob Haboldt, Marta Innocenti, Holger Jacob-Friesen, Neil Jeffares, Fritz Koreny, Marina Korobko, Annick Lemoine, Francesco Leone, Emmanuel et Laurie Marty de Cambiaire, Isabelle Mayer-Michalon, Christof Metzger, Jane Munro, Anna Ottani Cavina, Gianni Papi, Francesco Petrucci, Jane Roberts, Bernardina Sani, Bert Schepers and the Centrum Rubenianum, Keith Sciberras, Francesco Solinas, Rick Scorza, Paul Taylor and the Warburg Institute, Edouard Vignot, Alexandra Zvereva. Last but not least, I am equally grateful to my wife Cristina for her unrelenting patience and for her continued help and support. Jean-Luc Baroni All enquiries should be addressed to Jean-Luc Baroni at Jean-Luc Baroni Ltd. 7-8 Mason’s Yard, Duke Street, St. James’s, London SW1Y 6BU Tel. [44] (20) 7930-5347 e-mail: [email protected] www.jlbaroni.com © Copyright Jean-Luc Baroni Ltd., 2016 Designed and printed by ViolArt - Florence e-mail: [email protected] Front cover: Théodore Géricault, Portrait of Eugène Delacroix, no.12 (detail).