Chad in Its Regional Environment: Political Alliances and Ad Hoc Military Coalitions LIBYA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

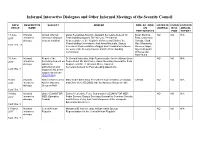

Informal Interactive Dialogues and Other Informal Meetings of the Security Council (As of 13 December 2019)

Informal Interactive Dialogues and Other Informal Meetings of the Security Council (as of 13 December 2019) DATE/ VENUE DESCRIPTIVE SUBJECT BRIEFERS NON‐SC / LISTED IN: NAME NON‐UN PARTICIPANTS JOURNAL SC ANNUAL POW REPORT 27 November 2019 Informal Peace consolidation in Abdoulaye Bathily, former head of the UN Regional Office for Central None NO NO N/A Conf. Rm. 7 interactive West Africa/UNOWAS Africa (UNOCA) and the author of the independent strategic review of dialogue the UN Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS); Bintou Keita (Assistant Secretary‐General for Africa); Guillermo Fernández de Soto Valderrama (Permanent Representative of Colombia and Peace Building Commission Chair) 28 August 2019 Informal The situation in Burundi Michael Kingsley‐Nyinah (Director for Central and Southern Africa United Republic of NO NO N/A Conf. Rm. 6 interactive Division, DPPA/DPO), Jürg Lauber (Switzerland PR as Chair of PBC Tanzania dialogue Burundi configuration) 31 July 2019 Informal Peace and security in Amira Elfadil Mohammed Elfadil (AU Comissioner for Social Affairs), Democratic Republic NO NO N/A Conf. Room 7 interactive Africa (Ebola outbreak in David Gressly (Ebola Emergency Response Coordinator), Mark Lowcock of the Congo dialogue the DRC) (Under‐Secretary‐General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator), Michael Ryan (WHO Health Emergencies Programme Executive Director) 7 June 2019 Informal The situation in Libya Mr. Pedro Serrano, Deputy Secretary General of the European External none NO NO N/A Conf. Rm. 7 interactive (Resolution 2292 (2016) Action Service dialogue implementation) 21 March 2019 Informal The situation in the Joost R. Hiltermann (Program Director for Middle East & North Africa, NO NO N/A Conf. -

SIPRI Yearbook 2004: Armaments, Disarmament and International

Annex B. Chronology 2003 NENNE BODELL and CONNIE WALL For the convenience of the reader, key words are indicated in the right-hand column, opposite each entry. They refer to the subject-areas covered in the entry. Definitions of the acronyms appear in the glossary on page xviii. The dates are according to local time. 1 Jan. The Document on Confidence- and Security-Building Meas- Black Sea; ures in the Naval Field in the Black Sea, signed on 25 Apr. CBMs 2002 by Bulgaria, Georgia, Romania, Russia, Turkey and Ukraine, enters into force. 1 Jan. The mission of the OSCE Assistance Group to Chechnya OSCE; ceases its activities as the Organization for Security and Chechnya Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) participating states are unable to agree on an extension of its mandate. 1 Jan. The European Union Police Mission (EUPM) begins its work EU; Bosnia and in Sarajevo. It is the first EU civil crisis-management mission Herzegovina within the framework of the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP). 6 Jan. The Board of Governors of the International Atomic Energy North Korea; Agency (IAEA) adopts Resolution GOV/2003/3 on the imple- IAEA; mentation of NPT safeguards in North Korea, demanding the Safeguards re-admission of IAEA inspectors to North Korea. 9 Jan. Chadian Foreign Minister Mahamat Saleh Annadif and Chad Alliance Nationale de la Résistance (ANR, National Resistance Army) representative Mahamat Garfa sign, in Libreville, Gabon, a peace agreement providing for an immediate cease- fire and a general amnesty for all ANR fighters and supporters. 10 Jan. The Government of North Korea announces its immediate North Korea; withdrawal from the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and its NPT; total freedom from the binding force of its NPT safeguards Safeguards agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), but states that it has no intention to produce nuclear weapons. -

S/PV.8229 the Situation in Mali 11/04/2018

United Nations S/ PV.8229 Security Council Provisional Seventy-third year 8229th meeting Wednesday, 11 April 2018, 10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Meza-Cuadra ............................... (Peru) Members: Bolivia (Plurinational State of) ..................... Mr. Llorentty Solíz China ......................................... Mr. Zhang Dianbin Côte d’Ivoire ................................... Mr. Tanoh-Boutchoue Equatorial Guinea ............................... Mr. Ndong Mba Ethiopia ....................................... Mr. Alemu France ........................................ Mr. Delattre Kazakhstan .................................... Mr. Tumysh Kuwait ........................................ Mr. Alotaibi Netherlands .................................... Mr. Van Oosterom Poland ........................................ Ms. Wronecka Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Polyanskiy Sweden ....................................... Mr. Skoog United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .. Ms. Pierce United States of America .......................... Ms. Tachco Agenda The situation in Mali Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Mali (S/2018/273) This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy of the record and sent under the signature of a member -

War Crimes Prosecution Watch, Vol. 15, Issue 4

War Crimes Prosecution Watch Editor-in-Chief David Krawiec FREDERICK K. COX Volume 15 - Issue 4 INTERNATIONAL LAW CENTER April 11, 2020 Technical Editor-in-Chief Erica Hudson Founder/Advisor Michael P. Scharf Managing Editors Matthew Casselberry Faculty Advisor Alexander Peters Jim Johnson War Crimes Prosecution Watch is a bi-weekly e-newsletter that compiles official documents and articles from major news sources detailing and analyzing salient issues pertaining to the investigation and prosecution of war crimes throughout the world. To subscribe, please email [email protected] and type "subscribe" in the subject line. Opinions expressed in the articles herein represent the views of their authors and are not necessarily those of the War Crimes Prosecution Watch staff, the Case Western Reserve University School of Law or Public International Law & Policy Group. Contents AFRICA NORTH AFRICA Libya Course of coronavirus pandemic across Libya, depends on silencing the guns (UN News) Libya government: ‘UAE drones targeted post office in Sirte’ (Middle East Monitor) CENTRAL AFRICA Central African Republic Sudan & South Sudan Democratic Republic of the Congo Convicted Congolese Warlord Escapes. Again. (Human Rights Watch) WEST AFRICA Côte d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast) Lake Chad Region — Chad, Nigeria, Niger, and Cameroon Mali Atrocity Alert No. 196: Yemen, South Sudan and Mali (reliefweb) Liberia Belgian investigators drag feet on Martina Johnson; Liberia’s War Criminal (Global News Network) George Dweh, Notorious Civil War Actor, Is Dead (Daily -

S/2016/281 Security Council

United Nations S/2016/281 Security Council Distr.: General 28 March 2016 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Mali I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 2227 (2015), by which the Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) until 30 June 2016 and requested me to report every three months on the situation in Mali, focusing on progress in the implementation of the Agreement on Peace and Reconciliation in Mali and the efforts of MINUSMA to support it. It covers the period from 17 December 2015 to 18 March 2016. II. Major political developments 2. While the reporting period was characterized by some progress in the implementation of the peace agreement, maintaining the new momentum that had emerged towards the end of 2015, significant challenges remained. The Government took steps to advance political and institutional reforms, decentralization and the cantonment and disarmament, demobilization and reintegration processes. The Government, the Coordination des mouvements de l’Azawad (CMA) and the Platform coalition of armed groups constructively participated in all deliberations of the Agreement Monitoring Committee and renewed their commitment to accelerating the implementation of the agreement. Those positive developments notwithstanding, the reporting period also saw continued delays in the implementation of key provisions of the agreement, such as the establishment of interim authorities in the north. This has been the priority of the signatory armed groups. Implementation of the peace agreement: political and institutional measures 3. On 18 January, in Algiers, Algeria convened a high-level consultative meeting of the members of the Agreement Monitoring Committee to encourage the Malian parties to revive the peace process and implement the agreement without further delay. -

Monthly Forecast

September 2013 Monthly Forecast 2 In Hindsight: Overview Penholders 3 Status Update since our August Forecast Australia will preside over the Security Council Assistance Mission in Somalia, most likely by 4 Small Arms in September. its head and Special Representative of the Sec- A debate on small arms is planned during the retary-General Nicholas Kay and AU Special 6 Central African Republic high-level week of the General Assembly. The Representative Mahamat Saleh Annadif (both Prime Minister of Australia may preside with likely to brief by videoconferencing). 7 Liberia other members likely to be represented at min- Briefings in consultations are likely on: 8 Sierra Leone isterial or higher levels. The Secretary-General is • current issues of concern, under the “horizon 10 Guinea-Bissau expected to brief and a resolution is the expected scanning” formula, by a top official from the 11 Libya outcome. Department of Political Affairs; 12 South Sudan and The quarterly debate on the situation in • Sudan and South Sudan issues, twice, on at Sudan Afghanistan is also expected, with Ján Kubiš, the least one of these occasions most likely by Special Representative of the Secretary-Gen- Special Envoy of the Secretary-General Haile 14 Somalia eral and head of the UN Assistance Mission in Menkerios; 16 Yemen Afghanistan, likely to brief. • Guinea-Bissau, by the Secretary-General’s 17 UNDOF (Golan Heights) A briefing onYemen is expected by the Sec- Special Representative and head of the UN 18 Afghanistan retary-General’s Special Advisor, Jamal Beno- Integrated Peacebuilding Office in Guinea- 20 Notable Dates mar, as well as the Secretary-General of the Gulf Bissau, José Ramos-Horta; Cooperation Council, Abdullatif bin Rashid Al- • the Secretary-General’s report on the UN Zayani, and a senior representative of Yemen. -

S/PV.8497 the Situation in Mali 29/03/2019

United Nations S/ PV.8497 Security Council Provisional Seventy-fourth year 8497th meeting Friday, 29 March 2019, 2.30 p.m. New York President: Mr. Le Drian ................................... (France) Members: Belgium ....................................... Mr. Pecsteen de Buytswerve China ......................................... Mr. Ma Zhaoxu Côte d’Ivoire ................................... Mr. Amon-Tanoh Dominican Republic .............................. Mr. Singer Weisinger Equatorial Guinea ............................... Mrs. Mele Colifa Germany ...................................... Mr. Maas Indonesia. Mr. Djani Kuwait ........................................ Mr. Alotaibi Peru .......................................... Mr. Meza-Cuadra Poland ........................................ Ms. Wronecka Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Polyanskiy South Africa ................................... Mr. Matjila United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .. Lord Ahmad United States of America .......................... Mr. Hale Agenda The situation in Mali Report of the Secretary-General on the implementation of paragraph 4 of Security Council resolution 2423 (2018) (S/2019/207) Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Mali (S/2019/262) . This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages -

Informal Interactive Dialogues and Other Informal Meetings of the Security Council

Informal Interactive Dialogues and Other Informal Meetings of the Security Council DATE/ DESCRIPTIVE SUBJECT BRIEFER NON- SC / NON- LISTED IN LISTED LISTED IN VENUE NAME UN JOURNAL IN SC ANNUAL PARTICIPANTS POW REPORT 19 June Informal Annual informal Oscar Fernández-Taranco, Assistant Secretary-General for Brazil, Burkina NO NO N/A 2017 interactive interactive dialogue Peacebuilding Support; Tae-Yul Cho, Permanent Faso, Cameroon, dialogue on peacebuilding Representative of the Republic of Korea and Chair of the Canada, Chad, Peacebuilding Commission; Ihab Awad Moustafa, Deputy Mali, Mauritania, Conf. Rm. 12 Permanent Representative of Egypt and Coordinator between Morocco, Niger, the work of the Security Council and the Peacebuilding Nigeria Republic Commission of Korea and Switzerland 15 June Informal Report of the Dr. Donald Kaberuka, High Representative for the African Union NO NO N/A 2017 interactive Secretary-General on Peace Fund, Mr. Atul Khare, Under-Secretary-General for Field dialogue options for Support, and Mr. El-Ghassim Wane, Assistant authorization and Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations Conf. Rm. 7 support to AU peace support operations (S/2017/454) 9 June Informal Haiti / Activities of the Marc-André Blanchard, Permanent Representative of Canada Canada NO NO N/A 2017 interactive Ad Hoc Advisory and Chair of the ECOSOC Ad Hoc Advisory Group on Haiti dialogue Group on Haiti Conf. Rm. 7 31 May Informal Libya / EUNAVFOR Enrico Credentino, Force Commander of EUNAVFOR MED; NO NO N/A 2017 interactive MED (Operation Pedro Serrano, Deputy Secretary General for Common Security dialogue Sophia) and Defence Policy and Crisis Response at the European External Action Service Conf. -

Political Manipulation at Home, Military Intervention Abroad, Challenging Times Ahead

[PEACEW RKS [ DÉBY’S CHAD POLITICAL MANIPULATION AT HOME, MILITARY INTERVENTION ABROAD, CHALLENGING TIMES AHEAD Jérôme Tubiana and Marielle Debos ABOUT THE REPORT This report examines Chad’s political system, which has kept President Idriss Déby in power for twenty-seven years, and recent foreign policy, which is most notable for a series of regional military interventions, to assess the impact of domestic politics on Chad’s current and future regional role—and vice versa. A joint publication of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) and the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), the report is derived from several hundred interviews conducted in Chad, the Central African Republic, Niger, France, and other countries, between October 2015 and October 2017 as well as desk research. Unless otherwise cited, statements in this report are drawn from these interviews. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jérôme Tubiana is a researcher who specializes in Chad, Sudan, and South Sudan. He has conducted numerous field research missions in conflict areas for various organizations, most notably the Small Arms Survey and the International Crisis Group. His publications include two studies on Darfur for USIP, a book on the Darfur conflict (Chroniques du Darfour, 2010), and various articles in Foreign Affairs, Foreign Policy, the London Review of Books, and Le Monde diplomatique. Marielle Debos is an associate professor in political science at the University Paris Nanterre and a member of the Institute for Social Sciences of Politics. Before her appointment at Nanterre, she was a Marie Curie fellow at the University of California, Berkeley. She is the author of Living by the Gun in Chad: Combatants, Impunity and State Formation (2016). -

AU Special Representative Relocates to Mogadishu Meets with Visiting Burundi Delegation

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA African Union Mission for Somalia P.O. Box 20182- 00200; Tel: (+254-20) 271 3755/56/58; Fax: 271 3766, Nairobi, Kenya PRESS RELEASE (For immediate release) AU Special Representative relocates to Mogadishu meets with visiting Burundi delegation Mogadishu – February 10th, 2013; The Special Representative of the Chairperson of the African Union Commission (SRCC) for Somalia, Ambassador Mahamat Saleh Annadif has today officially relocated to Mogadishu, Somalia. Ambassador Annadif who took over the position of SRCC for Somalia in November last year has been operating in Nairobi, Kenya. Meanwhile, the AU Special Representative for Somalia, Ambassador Mahamat Saleh Annadif has met with the visiting Burundi delegation comprising mainly Members of Parliament which paid a coutesy call on him in his office in Mogadishu. Ambassador Annadif expressed his appreciation to members of the delegation for taking time off their busy schedule to travel to Mogadishu to witness for themselves the good work that Burundi soldiers in conjunction with their colleagues from other African countries are doing to help Somalia achieve peace and stability. “Somalia is in the process of rebuilding its infrastructure as peace is returning to the country after more than two decades of civil war. This is therefore a very important time for you to visit your Somali counterparts to share ideas that can benefit the two countries”. He said. The delegation which arrived today and expected to leave on Thursday, will hold meetings with representatives of the Federal Government of Somalia, Members of Parliament, troops from the Burundi Contingent serving under AMISOM.Leader of the delegation, Mr. -

July 11, 2014

A Week in the Horn 11.7.2013 News in Brief Parliament adopts budget for the Ethiopian fiscal year 2007 (2014-15) Third anniversary of South Sudan’s independence: new calls for peace Ethiopia’s economic growth to be higher than previously estimated says IMF Second National Business Conference held in Addis Ababa An attack on Somalia’s Presidential Palace Failure to understand AU and IGAD aims in Somalia News in Brief African Union AU Commission Chairperson, Dr Zuma, expressed readiness to work together with the new members of the AU Panel of the Wise appointed at the Malabo Summit: Dr Lakhdar Brahimi (Algeria); Mr. Edem Kodjo (Togo); Dr Albina Faria de Assis Pereira Africano (Angola); Dr Luisa Diogo (Mozambique) and Dr Specioza Naigaga Wandira Kazibwe (Uganda). The Chairperson paid tribute to the outgoing Panel, chaired by the late President Ahmed Ben Bella, whose members, former President Kenneth Kaunda, Dr Salim Ahmed Salim, Madame Marie Madeleine Kalala-Ngoy, and Dr Mary Chinery Hesse, become Friends of the Panel. The World Food Program (WFP) and the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) have launched an urgent appeal to address a funding shortfall that has already resulted in reduced monthly food allocations for nearly 800,000 refugees in 22 African countries. WFP is appealing for US$186 million to maintain its food assistance through the end of the year; UNHCR is asking for $39 million to fund nutritional support and food security activities. Worst affected are refugees in Chad, Central African Republic and South Sudan. Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma, on Thursday (July 10) appointed Dr. -

Africa's Cities of the Future

April 2016 www.un.org/africarenewal Africa’s cities of the future ccccc Interview: Joan Clos, UN-Habitat Bamboo: Africa’s untapped potential CONTENTS April 2016 | Vol. 30 No. 1 4 SPECIAL FEATURE COVER STORY Africa’s cities of the future 6 Kigali sparkles on the hills 8 Lagos wears a new look Joan Clos: Urbanization is a tool for development 10 UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (in orange tie) 12 Abidjan regains it glamour at the closing of the Climate Summit in Paris last December. UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe ALSO IN THIS ISSUE 14 David Nabarro: No one will be left behind 16 Africa looks to its entrepreneurs Mbeki panel ramps up war against illicit financial flows 18 Editor-in-Chief 20 Boost in Japan-Africa ties Masimba Tafirenyika 22 Bamboo: Africa’s untapped potential Managing Editor The Paris climate deal and Africa 26 Zipporah Musau 28 Solar: Harvesting the sun 30 A new Burkina Faso in the making? Sub-editor Kingsley Ighobor 32 Terrorism overshadows internal conflicts 36 Somalia rising from the ashes Staff Writer 41 Speaking SDGs in African languages Franck Kuwonu Research & Media Liaison DEPARTMENTS Pavithra Rao 3 Watch Design & Production 42 Wired Paddy D. Ilos, II 43 Books 43 Appointments Administration Dona Joseph Cover photo: Kigali, the capital city of Rwanda. Panos/Sven Torfinn Distribution Atar Markman Africa Renewal is published in English and French organizations. Articles from this magazine may be by the Strategic Communications Division of the freely reprinted, with attribution to the author and United Nations Department of Public Information. to “United Nations Africa Renewal,” and a copy Its contents do not necessarily reflect the views of of the reproduced article would be appreciated.