Pyroclastic Eruptions (Pyroclastic from Greek Meaning “Fire-Broken”)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety: Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety

Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety: Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety Edited by Thomas J. Casadevall U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 2047 Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety held in Seattle, Washington, in July I991 @mposium sponsored by Air Line Pilots Association Air Transport Association of America Federal Aviation Administmtion National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Geological Survey amposium co-sponsored by Aerospace Industries Association of America American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Flight Safety Foundation International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth's Interior National Transportation Safety Board UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Map Distribution Box 25286, MS 306, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S.Government Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety (1st : 1991 Seattle, Wash.) Volcanic ash and aviation safety : proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety I edited by Thomas J. Casadevall ; symposium sponsored by Air Line Pilots Association ... [et al.], co-sponsored by Aerospace Indus- tries Association of America ... [et al.]. p. cm.--(US. Geological Survey bulletin ; 2047) "Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety held in Seattle, Washington, in July 1991." Includes bibliographical references. -

A Detection of Milankovitch Frequencies in Global Volcanic Activity

A detection of Milankovitch frequencies in global volcanic activity Steffen Kutterolf1*, Marion Jegen1, Jerry X. Mitrovica2, Tom Kwasnitschka1, Armin Freundt1, and Peter J. Huybers2 1Collaborative Research Center (SFB) 574, GEOMAR, Wischhofstrasse 1-3, 24148 Kiel, Germany 2Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA ABSTRACT 490 k.y. in the Central American Volcanic Arc A rigorous detection of Milankovitch periodicities in volcanic output across the Pleistocene- (CAVA; Fig. 1). We augment these data with Holocene ice age has remained elusive. We report on a spectral analysis of a large number of 42 tephra layers extending over ~1 m.y. found well-preserved ash plume deposits recorded in marine sediments along the Pacifi c Ring of in Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) and Fire. Our analysis yields a statistically signifi cant detection of a spectral peak at the obliquity Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Legs offshore period. We propose that this variability in volcanic activity results from crustal stress changes of Central America. The marine tephra records associated with ice age mass redistribution. In particular, increased volcanism lags behind in Central America are dated using estimated the highest rate of increasing eustatic sea level (decreasing global ice volume) by 4.0 ± 3.6 k.y. sedimentation rates and/or through correlation and correlates with numerical predictions of stress changes at volcanically active sites. These with radiometrically dated on-land deposits results support the presence of a causal link between variations in ice age climate, continental (e.g., Kutterolf et al., 2008; also see the GSA stress fi eld, and volcanism. -

Extending the Late Holocene White River Ash Distribution, Northwestern Canada STEPHEN D

ARCTIC VOL. 54, NO. 2 (JUNE 2001) P. 157– 161 Extending the Late Holocene White River Ash Distribution, Northwestern Canada STEPHEN D. ROBINSON1 (Received 30 May 2000; accepted in revised form 25 September 2000) ABSTRACT. Peatlands are a particularly good medium for trapping and preserving tephra, as their surfaces are wet and well vegetated. The extent of tephra-depositing events can often be greatly expanded through the observation of ash in peatlands. This paper uses the presence of the White River tephra layer (1200 B.P.) in peatlands to extend the known distribution of this late Holocene tephra into the Mackenzie Valley, northwestern Canada. The ash has been noted almost to the western shore of Great Slave Lake, over 1300 km from the source in southeastern Alaska. This new distribution covers approximately 540000 km2 with a tephra volume of 27 km3. The short time span and constrained timing of volcanic ash deposition, combined with unique physical and chemical parameters, make tephra layers ideal for use as chronostratigraphic markers. Key words: chronostratigraphy, Mackenzie Valley, peatlands, White River ash RÉSUMÉ. Les tourbières constituent un milieu particulièrement approprié au piégeage et à la conservation de téphra, en raison de l’humidité et de l’abondance de végétation qui règnent en surface. L’observation des cendres contenues dans les tourbières permet souvent d’élargir notablement les limites spatiales connues des épisodes de dépôts de téphra. Cet article recourt à la présence de la couche de téphra de la rivière White (1200 BP) dans les tourbières pour agrandir la distribution connue de ce téphra datant de l’Holocène supérieur dans la vallée du Mackenzie, située dans le Nord-Ouest canadien. -

(2000), Voluminous Lava-Like Precursor to a Major Ash-Flow

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 98 (2000) 153–171 www.elsevier.nl/locate/jvolgeores Voluminous lava-like precursor to a major ash-flow tuff: low-column pyroclastic eruption of the Pagosa Peak Dacite, San Juan volcanic field, Colorado O. Bachmanna,*, M.A. Dungana, P.W. Lipmanb aSection des Sciences de la Terre de l’Universite´ de Gene`ve, 13, Rue des Maraıˆchers, 1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland bUS Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Rd, Menlo Park, CA, USA Received 26 May 1999; received in revised form 8 November 1999; accepted 8 November 1999 Abstract The Pagosa Peak Dacite is an unusual pyroclastic deposit that immediately predated eruption of the enormous Fish Canyon Tuff (ϳ5000 km3) from the La Garita caldera at 28 Ma. The Pagosa Peak Dacite is thick (to 1 km), voluminous (Ͼ200 km3), and has a high aspect ratio (1:50) similar to those of silicic lava flows. It contains a high proportion (40–60%) of juvenile clasts (to 3–4 m) emplaced as viscous magma that was less vesiculated than typical pumice. Accidental lithic fragments are absent above the basal 5–10% of the unit. Thick densely welded proximal deposits flowed rheomorphically due to gravitational spreading, despite the very high viscosity of the crystal-rich magma, resulting in a macroscopic appearance similar to flow- layered silicic lava. Although it is a separate depositional unit, the Pagosa Peak Dacite is indistinguishable from the overlying Fish Canyon Tuff in bulk-rock chemistry, phenocryst compositions, and 40Ar/39Ar age. The unusual characteristics of this deposit are interpreted as consequences of eruption by low-column pyroclastic fountaining and lateral transport as dense, poorly inflated pyroclastic flows. -

Mount Vesuvius Is Located on the Gulf of Naples, in Italy

Mount Vesuvius is located on the Gulf of Naples, in Italy. It is close to the coast and lies around 9km from the city of Naples. Despite being the only active volcano on mainland Europe, and one of the most dangerous volcanoes, almost 3 million people live in the immediate area. Did you know..? Mount Vesuvius last erupted in 1944. Photo courtesy of Ross Elliot(@flickr.com) - granted under creative commons licence – attribution Mount Vesuvius is one of a number of volcanoes that form the Campanian volcanic arc. This is a series of volcanoes that are active, dormant or extinct. Vesuvius Campi Flegrei Stromboli Mount Vesuvius is actually a Vulcano Panarea volcano within a volcano. Mount Etna Somma is the remain of a large Campi Flegrei del volcano, out of which Mount Mar di Sicilia Vesuvius has grown. Did you know..? Mount Vesuvius is 1,281m high. Mount Etna is another volcano in the Campanian arc. It is Europe’s most active volcano. Mount Vesuvius last erupted in 1944. This was during the Second World War and the eruption caused great problems for the newly arrived Allied forces. Aircraft were destroyed, an airbase was evacuated and 26 people died. Three villages were also destroyed. 1944 was the last recorded eruption but scientists continue to monitor activity as Mount Vesuvius is especially dangerous. Did you know..? During the 1944 eruption, the lava flow stopped at the steps of the local church in the village of San Giorgio a Cremano. The villagers call this a miracle! Photo courtesy of National Museum of the U.S. -

Eruption Styles

eerruuppttiioonn ssttyylleess OIKOS > volcano > mechanism >eruption styles z z z Why do some volcanoes erupt violently and others do not? The z z viscosity of magma and lava determines how a volcano will behave. z z Volcanoes that are highly explosive and therefore dangerous to z z people are built-up as highly viscous magma that forces its way to z z the surface, often exploding violently as trapped gasses try to z z escape. Volcanoes that are less explosive and less of a threat to z z people are made up of very fluid magmas. Fluid magma allows z z gasses to escape and therefore are less explosive. There are three z z factors that determine the viscosity of a magma and its resulting z z z lava: z z a) chemical composition of magma: which means silica content z z (amount of SiO2). Magma with a high silica content are sticky and z more viscous. b) magma temperature e viscosity: usually lava is between 600 and 1200 degrees Celcius. Basaltic lavas have the highest temperatures up to 1200 C. Rhyolitic and andesitic lavas are cooler when they erupt. The higher the temperature, the less vacuous magma will be. c) volume of dissolved gasses in magma. As gasses escape from magma in the vent as pressure is released, they propel material out in an explosive way. As magma moves to the surface through a vent, the confining pressure of the surrounding environment decreases rapidly. This reduction of the confining pressure allows the dissolved gases to be released suddenly. The escaping gases in the magma expand and may occupy hundreds of times their original volume. -

Explosive Eruptions

Explosive Eruptions -What are considered explosive eruptions? Fire Fountains, Splatter, Eruption Columns, Pyroclastic Flows. Tephra – Any fragment of volcanic rock emitted during an eruption. Ash/Dust (Small) – Small particles of volcanic glass. Lapilli/Cinders (Medium) – Medium sized rocks formed from solidified lava. – Basaltic Cinders (Reticulite(rare) + Scoria) – Volcanic Glass that solidified around gas bubbles. – Accretionary Lapilli – Balls of ash – Intermediate/Felsic Cinders (Pumice) – Low density solidified ‘froth’, floats on water. Blocks (large) – Pre-existing rock blown apart by eruption. Bombs (large) – Solidified in air, before hitting ground Fire Fountaining – Gas-rich lava splatters, and then flows down slope. – Produces Cinder Cones + Splatter Cones – Cinder Cone – Often composed of scoria, and horseshoe shaped. – Splatter Cone – Lava less gassy, shape reflects that formed by splatter. Hydrovolcanic – Erupting underwater (Ocean or Ground) near the surface, causes violent eruption. Marr – Depression caused by steam eruption with little magma material. Tuff Ring – Type of Marr with tephra around depression. Intermediate Magmas/Lavas Stratovolcanoes/Composite Cone – 1-3 eruption types (A single eruption may include any or all 3) 1. Eruption Column – Ash cloud rises into the atmosphere. 2. Pyroclastic Flows Direct Blast + Landsides Ash Cloud – Once it reaches neutral buoyancy level, characteristic ‘umbrella cap’ forms, & debris fall. Larger ash is deposited closer to the volcano, fine particles are carried further. Pyroclastic Flow – Mixture of hot gas and ash to dense to rise (moves very quickly). – Dense flows restricted to valley bottoms, less dense flows may rise over ridges. Steam Eruptions – Small (relative) steam eruptions may occur up to a year before major eruption event. . -

Canadian Volcanoes, Based on Recent Seismic Activity; There Are Over 200 Geological Young Volcanic Centres

Volcanoes of Canada 1 V4 C.J. Hickson and M. Ulmi, Jan. 3, 2006 • Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics Where do volcanoes occur? Driving forces • Volcano chemistry and eruption types • Volcanic Hazards Pyroclastic flows and surges Lava flows Ash fall (tephra) Lahars/Debris Flows Debris Avalanches Volcanic Gases • Anatomy of an Eruption – Mt. St. Helens • Volcanoes of Canada Stikine volcanic belt Presentation Outline Anahim volcanic belt Wells Gray – Clearwater volcanic field 2 Garibaldi volcanic belt • USA volcanoes – Cascade Magmatic Arc V4 Volcanoes in Our Backyard Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics In Canada, British Columbia and Yukon are the host to a vast wealth of volcanic 3 landforms. V4 How many active volcanoes are there on Earth? • Erupting now about 20 • Each year 50-70 • Each decade about 160 • Historical eruptions about 550 Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics • Holocene eruptions (last 10,000 years) about 1500 Although none of Canada’s volcanoes are erupting now, they have been active as recently as a couple of 4 hundred years ago. V4 The Earth’s Beginning Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 5 V4 The Earth’s Beginning These global forces have created, mountain Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics ranges, continents and oceans. 6 V4 continental crust ic ocean crust mantle Where do volcanoes occur? Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 7 V4 Driving Forces: Moving Plates Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 8 V4 Driving Forces: Subduction Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 9 V4 Driving Forces: Hot Spots Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 10 V4 Driving Forces: Rifting Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics Ocean plates moving apart create new crust. -

Largest Explosive Eruption in Historical Times in the Andes at A.D

b- Largest explosive eruption in historical times in the Andes at A.D. Huaynaputina volcano, 1600, southern Peru Jean-Claude ThOuret* IRD and Instituto Geofisicodel PerÚ, Calle Calatrava 21 6. Urbanización Camino Real, La Molina, Lima 12, Perú Jasmine Davila Instituto Geofísico del Perú, Lima, Perú Jean-Philippe Eissen IRD Centre de Brest BP 70, 29280 Plouzane Cedex, France ABSTRACT lent [DREI volume. km': Table The The largest esplosive eruption (volcanic explosivity index of 6) in historical times in the 4.4-5.6 I). tephra is composed of -SO% pumice with rhyolitic Andes took place in 1600 at Huaynaputina volcano in southern Peru. According to chroni- A.D. glass, crystals (mostly amphibole and bio- cles, the eruption began on February 19 with a Plinian phase and lasted until March 6. Repeated 15% tite), and 5% xenoliths including hydrothermally tephra falls, pyroclastic flows, and surges devastated an area 70 x 40 kni? west of the vent and altered fragments from the volcanic and sedimen- affected all of southern Peru, and earthquakes shook the city of Arequipa 75 km away. Eight tnry bedrock, and a small amount of accessory lwa deposits, totaling 10.2-13.1 km3 in bulk volume, are attributed to this eruption: (1) a widespread, fragments. The erupted pumice is a white, , -S.1 kn3 pumice-fall deposit; (2) channeled ignimbrites (1.6-2 km3) with (3) ground-surge and medium-potassicdacite (average SiO, and ash-cloud-surge deposits; (4) widespread co-ignimbrite ash layers; (5) base-surge deposits; (6) 63.6% 1.85% hlgO) of the potassic calc-alkalic suite. -

Eruption Dynamics of Magmatic/Phreatomagmatic Eruptions of Low-Viscosity Phonolitic Magmas: Case of the Laacher See Eruption (Eifel, Germany)

FACULTEIT WETENSCHAPPEN Opleiding Master in de Geologie Eruption dynamics of magmatic/phreatomagmatic eruptions of low-viscosity phonolitic magmas: Case of the Laacher See eruption (Eifel, Germany) Gert-Jan Peeters Academiejaar 2011–2012 Scriptie voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad Van Master in de Geologie Promotor: Prof. Dr. V. Cnudde Co-promotor: Dr. K. Fontijn, Dr. G. Ernst Leescommissie: Prof. Dr. P. Vandenhaute, Prof. Dr. M. Kervyn Foreword There are a few people who I would like to thank for their efforts in helping me conduct the research necessary to write this thesis. Firstly, I would specially like to thank my co-promotor Dr. Karen Fontijn for all the time she put into this thesis which is a lot. Even though she was abroad most of the year, she was always there to help me and give me her opinion/advice whether by e-mail or by Skype and whether it was in the early morning or at midnight. Over the past three years, I learned a lot from her about volcanology and conducting research in general going from how volcanic deposits look on the field and how to sample them to how to measure accurately and systematically in the laboratory to ultimately how to write scientifically. I would also like to thank my promoter Prof. Dr. Veerle Cnudde for giving me the opportunity to do my thesis about volcanology even though it is not in her area of expertise and the opportunity to use the µCT multiple times. I thank the entire UGCT especially Wesley De Boever, Tim De Kock, Marijn Boone and Jan Dewanckele for helping me with preparing thin sections, drilling subsamples, explaining how Morpho+ works, solving problems when Morpho+ decided to crash etc. -

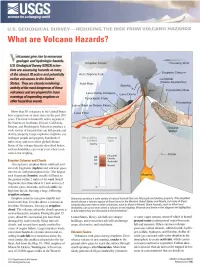

What Are Volcano Hazards?

USGS science for a changing world U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY REDUCING THE RISK FROM VOLCANO HAZARDS What are Volcano Hazards? \7olcanoes give rise to numerous T geologic and hydrologic hazards. Eruption Cloud Prevailing Wind U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) scien tists are assessing hazards at many Eruption Column of the almost 70 active and potentially Ash (Tephra) Fall active volcanoes in the United Landslide (Debris Avalanche) States. They are closely monitoring Acid Rain Bombs activity at the most dangerous of these Pyroclastic Flow volcanoes and are prepared to issue Lava Dome Collapse x Lava Dome warnings of impending eruptions or Pyroclastic Flow other hazardous events. Lahar (Mud or Debris Flow)jX More than 50 volcanoes in the United States Lava Flow have erupted one or more times in the past 200 years. The most volcanically active regions of the Nation are in Alaska, Hawaii, California, Oregon, and Washington. Volcanoes produce a wide variety of hazards that can kill people and destroy property. Large explosive eruptions can endanger people and property hundreds of miles away and even affect global climate. Some of the volcano hazards described below, such as landslides, can occur even when a vol cano is not erupting. Eruption Columns and Clouds An explosive eruption blasts solid and mol ten rock fragments (tephra) and volcanic gases into the air with tremendous force. The largest rock fragments (bombs) usually fall back to the ground within 2 miles of the vent. Small fragments (less than about 0.1 inch across) of volcanic glass, minerals, and rock (ash) rise high into the air, forming a huge, billowing eruption column. -

Explosive Caldera-Forming Eruptions and Debris-Filled Vents: Gargle Dynamics Greg A

https://doi.org/10.1130/G48995.1 Manuscript received 26 February 2021 Revised manuscript received 15 April 2021 Manuscript accepted 20 April 2021 © 2021 The Authors. Gold Open Access: This paper is published under the terms of the CC-BY license. Explosive caldera-forming eruptions and debris-filled vents: Gargle dynamics Greg A. Valentine* and Meredith A. Cole Department of Geology, University at Buffalo, 126 Cooke Hall, Buffalo, New York 14260, USA ABSTRACT conservation equations solved for both gas and Large explosive volcanic eruptions are commonly associated with caldera subsidence and particles, which are coupled through momentum ignimbrites deposited by pyroclastic currents. Volumes and thicknesses of intracaldera and (drag) and heat exchange (as in Sweeney and outflow ignimbrites at 76 explosive calderas around the world indicate that subsidence is com- Valentine, 2017; Valentine and Sweeney, 2018). monly simultaneous with eruption, such that large proportions of the pyroclastic currents The same approach was used to study discrete are trapped within the developing basins. As a result, much of an eruption must penetrate phreatomagmatic explosions in debris-filled its own deposits, a process that also occurs in large, debris-filled vent structures even in the vents (Sweeney and Valentine, 2015; Sweeney absence of caldera formation and that has been termed “gargling eruption.” Numerical et al., 2018), but here we focus on sustained dis- modeling of the resulting dynamics shows that the interaction of preexisting deposits (fill) charges. The simplified two-dimensional (2-D), with an erupting (juvenile) mixture causes a dense sheath of fill material to be lifted along axisymmetric model domain extends to an alti- the margins of the erupting jet.