Assessing Eruption Column Height in Ancient Flood Basalt Eruptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety: Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety

Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety: Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety Edited by Thomas J. Casadevall U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 2047 Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety held in Seattle, Washington, in July I991 @mposium sponsored by Air Line Pilots Association Air Transport Association of America Federal Aviation Administmtion National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Geological Survey amposium co-sponsored by Aerospace Industries Association of America American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Flight Safety Foundation International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth's Interior National Transportation Safety Board UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Map Distribution Box 25286, MS 306, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S.Government Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety (1st : 1991 Seattle, Wash.) Volcanic ash and aviation safety : proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety I edited by Thomas J. Casadevall ; symposium sponsored by Air Line Pilots Association ... [et al.], co-sponsored by Aerospace Indus- tries Association of America ... [et al.]. p. cm.--(US. Geological Survey bulletin ; 2047) "Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety held in Seattle, Washington, in July 1991." Includes bibliographical references. -

(2000), Voluminous Lava-Like Precursor to a Major Ash-Flow

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 98 (2000) 153–171 www.elsevier.nl/locate/jvolgeores Voluminous lava-like precursor to a major ash-flow tuff: low-column pyroclastic eruption of the Pagosa Peak Dacite, San Juan volcanic field, Colorado O. Bachmanna,*, M.A. Dungana, P.W. Lipmanb aSection des Sciences de la Terre de l’Universite´ de Gene`ve, 13, Rue des Maraıˆchers, 1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland bUS Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Rd, Menlo Park, CA, USA Received 26 May 1999; received in revised form 8 November 1999; accepted 8 November 1999 Abstract The Pagosa Peak Dacite is an unusual pyroclastic deposit that immediately predated eruption of the enormous Fish Canyon Tuff (ϳ5000 km3) from the La Garita caldera at 28 Ma. The Pagosa Peak Dacite is thick (to 1 km), voluminous (Ͼ200 km3), and has a high aspect ratio (1:50) similar to those of silicic lava flows. It contains a high proportion (40–60%) of juvenile clasts (to 3–4 m) emplaced as viscous magma that was less vesiculated than typical pumice. Accidental lithic fragments are absent above the basal 5–10% of the unit. Thick densely welded proximal deposits flowed rheomorphically due to gravitational spreading, despite the very high viscosity of the crystal-rich magma, resulting in a macroscopic appearance similar to flow- layered silicic lava. Although it is a separate depositional unit, the Pagosa Peak Dacite is indistinguishable from the overlying Fish Canyon Tuff in bulk-rock chemistry, phenocryst compositions, and 40Ar/39Ar age. The unusual characteristics of this deposit are interpreted as consequences of eruption by low-column pyroclastic fountaining and lateral transport as dense, poorly inflated pyroclastic flows. -

Volcanic Landforms: the Landform Which Is Formed from the Material Thrown out to the Surface During Volcanic Activity Is Called Extrusive Landform

Download Testbook App Volcanic Geography NCERT Notes Landforms For UPSC ABOUT VOLCANIC LANDFORM: Volcanic landform is categorised into two types they are:extrusive and intrusive landforms. This division is done based on whether magma cools within the crust or above the crust. By the cooling process of magma different types of rock are formed. Like: Plutonic rock, it is a rock which is magma within the crust whereas Igneous rock is formed by the cooling of lava above the surface. Along with that “igneous rock” term is also used to refer to all rocks of volcanic origin. Extrusive Volcanic Landforms: The landform which is formed from the material thrown out to the surface during volcanic activity is called extrusive landform. The materials which are thrown out during volcanic activity are: lava flows, pyroclastic debris, volcanic bombs, ash, dust and gases such as nitrogen compounds, sulphur compounds and minor amounts of chlorine, hydrogen and argon. Conical Vent and Fissure Vent: Conical Vent: It is a narrow cylindrical vent through which magma flows out violently. Such vents are commonly seen in andesitic volcanism. Fissure vent: Such vent is a narrow, linear through which lava erupts with any kind of explosive events. Such vents are usually seen in basaltic volcanism. Mid-Ocean Ridges: The volcanoes which are found in oceanic areas are called mid-ocean ridges. In them there is a system of mid-ocean ridges stretching for over 70000 km all through the ocean basins. And the central part of such a ridge usually gets frequent eruptions. Composite Type Volcanic Landforms: Such volcanic landforms are also called stratovolcanoes. -

Magma Emplacement and Deformation in Rhyolitic Dykes: Insight Into Magmatic Outgassing

MAGMA EMPLACEMENT AND DEFORMATION IN RHYOLITIC DYKES: INSIGHT INTO MAGMATIC OUTGASSING Presented for the degree of Ph.D. by Ellen Marie McGowan MGeol (The University of Leicester, 2011) Initial submission January 2016 Final submission September 2016 Lancaster Environment Centre, Lancaster University Declaration I, Ellen Marie McGowan, hereby declare that the content of this thesis is the result of my own work, and that no part of the work has been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere. This thesis is dedicated to Nan-Nar, who sadly passed away in 2015. Nan, you taught our family the importance and meaning of love, we love you. Abstract Exposed rhyolitic dykes at eroded volcanoes arguably provide in situ records of conduit processes during rhyolitic eruptions, thus bridging the gap between surface and sub-surface processes. This study involved micro- to macro-scale analysis of the textures and water content within shallow (emplacement depths <500 m) rhyolitic dykes at two Icelandic central volcanoes. It is demonstrated that dyke propagation commenced with the intrusion of gas- charged currents that were laden with particles, and that the distribution of intruded particles and degree of magmatic overpressure required for dyke propagation were governed by the country rock permeability and strength, with pre-existing fractures playing a pivotal governing role. During this stage of dyke evolution significant amounts of exsolved gas may have escaped. Furthermore, during later magma emplacement within the dyke interiors, particles that were intruded and deposited during the initial phase were sometimes preserved at the dyke margins, forming dyke- marginal external tuffisite veins, which would have been capable of facilitating persistent outgassing during dyke growth. -

Video Monitoring Reveals Pulsating Vents and Propagation Path of Fissure Eruption During the March 2011 Pu'u

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 330 (2017) 43–55 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jvolgeores Video monitoring reveals pulsating vents and propagation path of fissure eruption during the March 2011 Pu'u 'Ō'ō eruption, Kilauea volcano Tanja Witt ⁎,ThomasR.Walter GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Section 2.1: Physics of Earthquakes and Volcanoes, Telegrafenberg, 14473 Potsdam, Germany article info abstract Article history: Lava fountains are a common eruptive feature of basaltic volcanoes. Many lava fountains result from fissure erup- Received 12 April 2016 tions and are associated with the alignment of active vents and rising gas bubbles in the conduit. Visual reports Received in revised form 18 November 2016 suggest that lava fountain pulses may occur in chorus at adjacent vents. The mechanisms behind such a chorus of Accepted 18 November 2016 lava fountains and the underlying processes are, however, not fully understood. Available online 5 December 2016 The March 2011 eruption at Pu'u 'Ō'ō (Kilauea volcano) was an exceptional fissure eruption that was well mon- fi fi Keywords: itored and could be closely approached by eld geologists. The ssure eruption occurred along groups of individ- Kilauea volcano ual vents aligned above the feeding dyke. We investigate video data acquired during the early stages of the Fissure eruption eruption to measure the height, width and velocity of the ejecta leaving eight vents. Using a Sobel edge-detection Vent migration algorithm, the activity level of the lava fountains at the vents was determined, revealing a similarity in the erup- Bubbling magma tion height and frequency. -

Explosive Eruptions

Explosive Eruptions -What are considered explosive eruptions? Fire Fountains, Splatter, Eruption Columns, Pyroclastic Flows. Tephra – Any fragment of volcanic rock emitted during an eruption. Ash/Dust (Small) – Small particles of volcanic glass. Lapilli/Cinders (Medium) – Medium sized rocks formed from solidified lava. – Basaltic Cinders (Reticulite(rare) + Scoria) – Volcanic Glass that solidified around gas bubbles. – Accretionary Lapilli – Balls of ash – Intermediate/Felsic Cinders (Pumice) – Low density solidified ‘froth’, floats on water. Blocks (large) – Pre-existing rock blown apart by eruption. Bombs (large) – Solidified in air, before hitting ground Fire Fountaining – Gas-rich lava splatters, and then flows down slope. – Produces Cinder Cones + Splatter Cones – Cinder Cone – Often composed of scoria, and horseshoe shaped. – Splatter Cone – Lava less gassy, shape reflects that formed by splatter. Hydrovolcanic – Erupting underwater (Ocean or Ground) near the surface, causes violent eruption. Marr – Depression caused by steam eruption with little magma material. Tuff Ring – Type of Marr with tephra around depression. Intermediate Magmas/Lavas Stratovolcanoes/Composite Cone – 1-3 eruption types (A single eruption may include any or all 3) 1. Eruption Column – Ash cloud rises into the atmosphere. 2. Pyroclastic Flows Direct Blast + Landsides Ash Cloud – Once it reaches neutral buoyancy level, characteristic ‘umbrella cap’ forms, & debris fall. Larger ash is deposited closer to the volcano, fine particles are carried further. Pyroclastic Flow – Mixture of hot gas and ash to dense to rise (moves very quickly). – Dense flows restricted to valley bottoms, less dense flows may rise over ridges. Steam Eruptions – Small (relative) steam eruptions may occur up to a year before major eruption event. . -

LERZ) Eruption of Kīlauea Volcano: Fissure 8 Prognosis and Ongoing Hazards

COOPERATOR REPORT TO HAWAII COUNTY CIVIL DEFENSE Preliminary Analysis of the ongoing Lower East Rift Zone (LERZ) eruption of Kīlauea Volcano: Fissure 8 Prognosis and Ongoing Hazards Prepared by the U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory July 15, 2018 (V 1.1) Introduction In late April 2018, the long-lived Puʻu ʻŌʻō vent collapsed, setting off a chain of events that would result in a vigorous eruption in the lower East Rift Zone of Kīlauea Volcano, as well as the draining of the summit lava lake and magmatic system and the subsequent collapse of much of the floor of the Kīlauea caldera. Both events originated in Lava Flow Hazard Zone (LFHZ) 1 (Wright et al, 1992), which encompasses the part of the volcano that is most frequently affected by volcanic activity. We examine here the possible and potential impacts of the ongoing eruptive activity in the lower East Rift Zone (LERZ) of Kīlauea Volcano, and specifically that from fissure 8 (fig. 1). Fissure 8 has been the dominant lava producer during the 2018 LERZ eruption, which began on May 3, 2018, in Leilani Estates, following intrusion of magma from the middle and upper East Rift Zone, as well as the volcano’s summit, into the LERZ. The onset of downrift intrusion was accompanied by collapse of the Puʻu ʻŌʻō vent, which started on April 30 and lasted several days. Kīlauea Volcano's shallow summit magma reservoir began deflating on about May 2, illustrating the magmatic connection between the LERZ and the summit. Early LERZ fissures erupted cooler lava that had likely been stored within the East Rift Zone, but was pushed out in front of hotter magma arriving from farther uprift. -

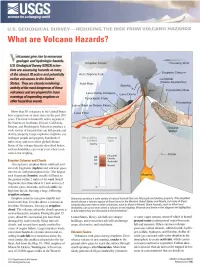

What Are Volcano Hazards?

USGS science for a changing world U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY REDUCING THE RISK FROM VOLCANO HAZARDS What are Volcano Hazards? \7olcanoes give rise to numerous T geologic and hydrologic hazards. Eruption Cloud Prevailing Wind U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) scien tists are assessing hazards at many Eruption Column of the almost 70 active and potentially Ash (Tephra) Fall active volcanoes in the United Landslide (Debris Avalanche) States. They are closely monitoring Acid Rain Bombs activity at the most dangerous of these Pyroclastic Flow volcanoes and are prepared to issue Lava Dome Collapse x Lava Dome warnings of impending eruptions or Pyroclastic Flow other hazardous events. Lahar (Mud or Debris Flow)jX More than 50 volcanoes in the United States Lava Flow have erupted one or more times in the past 200 years. The most volcanically active regions of the Nation are in Alaska, Hawaii, California, Oregon, and Washington. Volcanoes produce a wide variety of hazards that can kill people and destroy property. Large explosive eruptions can endanger people and property hundreds of miles away and even affect global climate. Some of the volcano hazards described below, such as landslides, can occur even when a vol cano is not erupting. Eruption Columns and Clouds An explosive eruption blasts solid and mol ten rock fragments (tephra) and volcanic gases into the air with tremendous force. The largest rock fragments (bombs) usually fall back to the ground within 2 miles of the vent. Small fragments (less than about 0.1 inch across) of volcanic glass, minerals, and rock (ash) rise high into the air, forming a huge, billowing eruption column. -

Explosive Caldera-Forming Eruptions and Debris-Filled Vents: Gargle Dynamics Greg A

https://doi.org/10.1130/G48995.1 Manuscript received 26 February 2021 Revised manuscript received 15 April 2021 Manuscript accepted 20 April 2021 © 2021 The Authors. Gold Open Access: This paper is published under the terms of the CC-BY license. Explosive caldera-forming eruptions and debris-filled vents: Gargle dynamics Greg A. Valentine* and Meredith A. Cole Department of Geology, University at Buffalo, 126 Cooke Hall, Buffalo, New York 14260, USA ABSTRACT conservation equations solved for both gas and Large explosive volcanic eruptions are commonly associated with caldera subsidence and particles, which are coupled through momentum ignimbrites deposited by pyroclastic currents. Volumes and thicknesses of intracaldera and (drag) and heat exchange (as in Sweeney and outflow ignimbrites at 76 explosive calderas around the world indicate that subsidence is com- Valentine, 2017; Valentine and Sweeney, 2018). monly simultaneous with eruption, such that large proportions of the pyroclastic currents The same approach was used to study discrete are trapped within the developing basins. As a result, much of an eruption must penetrate phreatomagmatic explosions in debris-filled its own deposits, a process that also occurs in large, debris-filled vent structures even in the vents (Sweeney and Valentine, 2015; Sweeney absence of caldera formation and that has been termed “gargling eruption.” Numerical et al., 2018), but here we focus on sustained dis- modeling of the resulting dynamics shows that the interaction of preexisting deposits (fill) charges. The simplified two-dimensional (2-D), with an erupting (juvenile) mixture causes a dense sheath of fill material to be lifted along axisymmetric model domain extends to an alti- the margins of the erupting jet. -

Eruptive Proceses Responsible for Fall Tephra in the Upper Miocene Peralta Tuff, Jemez Mountains, New Mexico Sharon Kundel and Gary A

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/58 Eruptive proceses responsible for fall tephra in the Upper Miocene Peralta Tuff, Jemez Mountains, New Mexico Sharon Kundel and Gary A. Smith, 2007, pp. 268-274 in: Geology of the Jemez Region II, Kues, Barry S., Kelley, Shari A., Lueth, Virgil W.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 58th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 499 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 2007 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. -

Lunar Crater Volcanic Field (Reveille and Pancake Ranges, Basin and Range Province, Nevada, USA)

Research Paper GEOSPHERE Lunar Crater volcanic field (Reveille and Pancake Ranges, Basin and Range Province, Nevada, USA) 1 2,3 4 5 4 5 1 GEOSPHERE; v. 13, no. 2 Greg A. Valentine , Joaquín A. Cortés , Elisabeth Widom , Eugene I. Smith , Christine Rasoazanamparany , Racheal Johnsen , Jason P. Briner , Andrew G. Harp1, and Brent Turrin6 doi:10.1130/GES01428.1 1Department of Geology, 126 Cooke Hall, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York 14260, USA 2School of Geosciences, The Grant Institute, The Kings Buildings, James Hutton Road, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH 3FE, UK 3School of Civil Engineering and Geosciences, Newcastle University, Newcastle, NE1 7RU, UK 31 figures; 3 tables; 3 supplemental files 4Department of Geology and Environmental Earth Science, Shideler Hall, Miami University, Oxford, Ohio 45056, USA 5Department of Geoscience, 4505 S. Maryland Parkway, University of Nevada Las Vegas, Las Vegas, Nevada 89154, USA CORRESPONDENCE: gav4@ buffalo .edu 6Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 610 Taylor Road, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854-8066, USA CITATION: Valentine, G.A., Cortés, J.A., Widom, ABSTRACT some of the erupted magmas. The LCVF exhibits clustering in the form of E., Smith, E.I., Rasoazanamparany, C., Johnsen, R., Briner, J.P., Harp, A.G., and Turrin, B., 2017, overlapping and colocated monogenetic volcanoes that were separated by Lunar Crater volcanic field (Reveille and Pancake The Lunar Crater volcanic field (LCVF) in central Nevada (USA) is domi variable amounts of time to as much as several hundred thousand years, but Ranges, Basin and Range Province, Nevada, USA): nated by monogenetic mafic volcanoes spanning the late Miocene to Pleisto without sustained crustal reservoirs between the episodes. -

Controls on Lunar Basaltic Volcanic Eruption Structure and Morphology: 2 Gas Release Patterns in Sequential Eruption Phases 3 L

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lancaster E-Prints 1 Controls on Lunar Basaltic Volcanic Eruption Structure and Morphology: 2 Gas Release Patterns in Sequential Eruption Phases 3 L. Wilson1,2 and J. W. Head2 4 1Lancaster Environment Centre, Lancaster University, Lancaster LA1 4YQ, UK 5 2Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences, Brown University, Providence, RI 6 02912 USA 7 8 Key Points: 9 Relationships between a diverse array of lunar mare effusive and explosive volcanic 10 deposits and landforms have previously been poorly understood. 11 Four stages in the generation, ascent and eruption of magma and gas release patterns are 12 identified and characterized. 13 Specific effusive, explosive volcanic deposits and landforms are linked to these four 14 stages in lunar mare basalt eruptions in a predictive and integrated manner. 15 16 Abstract 17 Assessment of mare basalt gas release patterns during individual eruptions provides the basis for 18 predicting the effect of vesiculation processes on the structure and morphology of associated 19 features. We subdivide typical lunar eruptions into four phases: Phase 1, dike penetrates to the 20 surface, transient gas release phase; Phase 2, dike base still rising, high flux hawaiian eruptive 21 phase; Phase 3, dike equilibration, lower flux hawaiian to strombolian transition phase; Phase 4, 22 dike closing, strombolian vesicular flow phase. We show how these four phases of mare basalt 23 volatile release, together with total dike volumes, initial magma volatile content, vent 24 configuration and magma discharge rate, can help relate the wide range of apparently disparate 25 lunar volcanic features (pyroclastic mantles, small shield volcanoes, compound flow fields, 26 sinuous rilles, long lava flows, pyroclastic cones, summit pit craters, irregular mare patches 27 (IMPs) and ring moat dome structures (RMDSs)) to a common set of eruption processes.