Navicula: a Psychedelic Grunge Band from Bali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sòouünd Póetry the Wages of Syntax

SòouÜnd Póetry The Wages of Syntax Monday April 9 - Saturday April 14, 2018 ODC Theater · 3153 17th St. San Francisco, CA WELCOME TO HOTEL BELLEVUE SAN LORENZO Hotel Spa Bellevue San Lorenzo, directly on Lago di Garda in the Northern Italian Alps, is the ideal four-star lodging from which to explore the art of Futurism. The grounds are filled with cypress, laurel and myrtle trees appreciated by Lawrence and Goethe. Visit the Mart Museum in nearby Rovareto, designed by Mario Botta, housing the rich archive of sound poet and painter Fortunato Depero plus innumerable works by other leaders of that influential movement. And don’t miss the nearby palatial home of eccentric writer Gabriele d’Annunzio. The hotel is filled with contemporary art and houses a large library https://www.bellevue-sanlorenzo.it/ of contemporary art publications. Enjoy full spa facilities and elegant meals overlooking picturesque Lake Garda, on private grounds brimming with contemporary sculpture. WElcome to A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC The 23rd Other Minds Festival is presented by Other Minds in 2 Message from the Artistic Director association with ODC Theater, 7 What is Sound Poetry? San Francisco. 8 Gala Opening All Festival concerts take place at April 9, Monday ODC Theater, 3153 17th St., San Francisco, CA at Shotwell St. and 12 No Poets Don’t Own Words begin at 7:30 PM, with the exception April 10, Tuesday of the lecture and workshop on 14 The History Channel Tuesday. Other Minds thanks the April 11, Wednesday team at ODC for their help and hard work on our behalf. -

Other Minds 19 Official Program

SFJAZZ CENTER SFJAZZ MINDS OTHER OTHER 19 MARCH 1ST, 2014 1ST, MARCH A FESTIVAL FEBRUARY 28 FEBRUARY OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC Find Left of the Dial in print or online at sfbg.com WELCOME A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED TO OTHER MINDS 19 NEW MUSIC The 19th Other Minds Festival is 2 Message from the Executive & Artistic Director presented by Other Minds in association 4 Exhibition & Silent Auction with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program and SFJazz Center 11 Opening Night Gala 13 Concert 1 All festival concerts take place in Robert N. Miner Auditorium in the new SFJAZZ Center. 14 Concert 1 Program Notes Congratulations to Randall Kline and SFJAZZ 17 Concert 2 on the successful launch of their new home 19 Concert 2 Program Notes venue. This year, for the fi rst time, the Other Minds Festival focuses exclusively on compos- 20 Other Minds 18 Performers ers from Northern California. 26 Other Minds 18 Composers 35 About Other Minds 36 Festival Supporters 40 About The Festival This booklet © 2014 Other Minds. All rights reserved. Thanks to Adah Bakalinsky for underwriting the printing of our OM 19 program booklet. MESSAGE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WELCOME TO OTHER MINDS 19 Ever since the dawn of “modern music” in the U.S., the San Francisco Bay Area has been a leading force in exploring new territory. In 1914 it was Henry Cowell leading the way with his tone clusters and strumming directly on the strings of the concert grand, then his students Lou Harrison and John Cage in the 30s with their percussion revolution, and the protégés of Robert Erickson in the Fifties with their focus on graphic scores and improvisation, and the SF Tape Music Center’s live electronic pioneers Subotnick, Oliveros, Sender, and others in the Sixties, alongside Terry Riley, Steve Reich and La Monte Young and their new minimalism. -

Downloaded From

Gunem Catur in the Sunda region of West Java : indigenous communication on MAC plant knowledge and practice within the Arisan in Lembang, Indonesia Djen Amar, S.C. Citation Djen Amar, S. C. (2010, October 19). Gunem Catur in the Sunda region of West Java : indigenous communication on MAC plant knowledge and practice within the Arisan in Lembang, Indonesia. Leiden Ethnosystems and Development Programme Studies. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/16092 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/16092 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). GUNEM CATUR IN THE SUNDA REGION OF WEST JAVA: INDIGENOUS COMMUNICATION ON THE MAC PLANT KNOWLEDGE AND PRACTICE WITHIN THE ARISAN IN LEMBANG, INDONESIA Siti Chaerani Djen Amar ii Gunem Catur in the Sunda Region of West Java: Indigenous Communication on MAC Plant Knowledge and Practice within the Arisan in Lembang, Indonesia iii iv Gunem Catur in the Sunda Region of West Java: Indigenous Communication on MAC Plant Knowledge and Practice within the Arisan in Lembang, Indonesia Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof.mr.dr. P.F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op dinsdag 19 oktober 2010 klokke 16.15 uur door Siti Chaerani Djen Amar geboren te Bandung, Indonesia in 1941 v Promotiecommisie: Promotor: Prof. Dr. L.J. Slikkerveer Overige leden: Prof.Dr. A.H. -

The Symbolic Regionalism on the Architectural Expression Design of Kupang Town-Hall

The Symbolic Regionalism on The Architectural Expression Design of Kupang Town-Hall Yohanes Djarot Purbadi1*, Reginaldo Christophori Lake2, Fransiscus Xaverius Eddy Arinto3 1,3Universitas Atma Jaya, Yogyakarta, Indonesia 2Universitas Katolik Widya Mandira, Kupang, Indonesia 1*[email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Published: 31 December 2020 This study aimed to explain the synthesis design approach of the architectural expression in the Town Hall building of Kupang city. This is necessary due to the need for Town Halls, as public facilities, to reflect technically correct building standards, environment, and the aspects of political symbolism. Kupang Town Hall design uses the roof image expression of the Timor, Flores, and Sumba ethnic architecture in a harmonious composition and this means it is an example of an ethnic architectural synthesis in a modern building which represents a function, meaning, modernity, and local cultural identity. This research employed the social semiotics method to examine the design in relation to the surrounding social life context and the design was found to be produced from the symbolic regionalism approach which involved mixing the architectural images of Timorese, Flores, and Sumba ethnicities to modernize and conserve ethnic architecture and represent the cultural identity of East Nusa Tenggara. This, therefore, means architectural synthesis methods which are established on the symbolic regionalism approach have the potential to be used in designing public facilities in different places of Indonesia to reveal local cultural identities in modern buildings through symbolism based on an ethnic architectural image. Keyword: Architecture expression, Ethnic architecture, Symbolic regionalism, Town-hall design 71 Journal of Design and Built Environment, Vol 20(3) 71-84, December 2020 Y.D. -

Pedoman Akademik 2019-2020

Pedoman Akademik dan Kemahasiswaan Universitas Sriwijaya Tahun Akademik 2019/2020 i Pedoman Akademik dan Kemahasiswaan Universitas Sriwijaya Tahun Akademik 2019/2020 KATA PENGANTAR Buku Pedoman Akademik dan Kemahasiswaan ini merupakan revisi Buku Pedoman Akademik 2018/2019 yang dilakukan Tim yang bekerja berdasarkan Surat Tugas Rektor Universitas Sriwijaya No: 0108/UN9/BAK.ST/2019. Buku ini terdiri dari 6 bab, memuat informasi umum meliputi penyelenggaraan kegiatan Akademik dan Kemahasiswaan di lingkungan Universitas Sriwijaya. Informasi lebih rinci mengenai penyelenggaraan kegiatan Tridharma untuk masing – masing Prodi dapat dilihat pada pedoman akademik masing-masing fakultas/program. Bab kesatu secara umum memuat informasi tentang Universitas Sriwijaya.Pada bab kedua dan selanjutnya berisi informasi teknis tentang prosedur, jalur penerimaan mahasiswa baru, peraturan akademik dan kemahasiswaan, beasiswa, asrama, transkrip, ijazah, wisuda dan lain-lain. Contoh formulir yang dipergunakan dalam pelayanan administrasi akademik dan kemahasiswaan disediakan didalam buku ini untuk mahasiswa yang memerlukan. Buku Pedoman ini masih memerlukan penyempurnaan agar dapat memenuhi kebutuhan informasi bagi pihak- pihak yang memerlukan, untuk itu masukan dari semua pihak sangat kami harapkan, sehingga pada edisi yang akan datang Buku Pedoman Akademik dan Kemahasiswaan ini menjadi lebih baik. Ucapan terima kasih secara khusus disampaikan kepada seluruh anggota tim dan para pihak yang telah berpartisipasi dalam menyusun buku ini. Semoga buku ini dapat -

From Koyasan to Borobudur Nasirun & Tanada Koji from Koyasan to Borobudur Nasirun & Tanada Koji

FROM KOYASAN TO BOROBUDUR NASIRUN & TANADA KOJI FROM KOYASAN TO BOROBUDUR NASIRUN & TANADA KOJI 16 JANUARY - 28 FEBRUARY 2016 at Mizuma Gallery in Tokyo, Nasirun DIALOGUE BETWEEN TWO CULTURES had a one-night stay in the spiritual NASIRUN AND TANADA KOJI city of Koyasan, the birthplace of Shingon Buddhism. This short stay in Koyasan left him with a very This exhibition is a dialogue in Indonesia often revere earth profound impression. Nasirun’s between Nasirun’s Javanese visual and natural spirits as the life-giving painting ‘Abstraksi Aura Alam’ language of wayang and Tanada mother. After the adoption of (Abstraction of Nature’s Aura) Koji’s ichiboku-zukuri, the ancient Hinduism, this mother figure was presented in this exhibition was traditional Japanese wood carving identified as Prithvi, the Hindu inspired by the Japanese garden in technique where sculptures are goddess of earth. Mother figure the Kongobuji Temple where the made by using single blocks of depicted in the series of paintings of archbishop of Koyasan Shingon-shu, wood. More over, the dialogue is Ibu Pertiwi is an analogy of Matsunaga Yukei, greeted Nasirun. mainly about their cultural points of Indonesia: a country and a mother view regarding the human for its people. To me the artworks presented in existence. this exhibition are beyond words Collaborative works between that I can think of, or knowledge In his artworks, Tanada Koji often Tanada Koji and Nasirun entitled that I can share. These artworks are depicts the figures of adolescent ‘sun and moon’ presented in this about deep and profound feelings. boys and girls. -

Rekind Untuk Ibu Pertiwi" Redaksi Menyapa

on i ovat N N I • k or w m a e T • l a N o i s s e f o r P • y t i r g e t N I • E S H Volume II/Maret 2020 R E K I N D Buletin PT Rekayasa Industri "Rekind untuk Ibu Pertiwi" Redaksi Menyapa REKIND UNTUK IBU PERTIWI Pagi-pagi kulihat gadis Di stasiun karet kala gerimis Semangat pagi Rekindist! Biar gerimis tetap optimis! Buletin Rekind Volume II siap menemani hari anda. “Rekind untuk Ibu Pertiwi” adalah tema yang diusung pada kesempatan ini. Sebagai wujud semangat Rekind di tahun 2020, tim buletin ingin mengulik dedikasi Rekind terhadap Indonesia di awal tahun ini. Dedikasi Rekind terhadap ibu pertiwi di awal tahun ini, terwujud dalam berbagai aktivitas Rekind, pengembangan infrastruktur Indonesia dalam PLTP Muara Laboh, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) dalam pengembangan kompetensi masyarakat Lansia, serta kepedulian dan ketanggapan Rekind dalam menanggulangi bencana alam. Perayaan tahun baru merupakan tragedi menyedihkan bagi warga ibukota, Rekind ikut membantu dengan memberikan fasilitas perahu karet dan bala bantuan bagi masyarakat Kalibata, Pejaten, dan sekitarnya. Rekindist akan melihat upaya Rekind dalam antisipasi banjir. Berbeda dengan ibukota, di Sumatera Barat, Rekindist merayakannya dengan peresmian PLTP Muara Laboh dan pencapaian Safety Manhours. Pembaca akan kami ajak berkeliling site Muara Laboh, mulai dari proyek, aktivitas Rekindist di site, hingga wisata di sekitar Muara Laboh. Aktivitas korporat di Rekind juga tak ketinggalan untuk dibahas. Keseruan Hi-Protein Day hingga program CSR Rekind yaitu “IMPALA Integrated Community”. Selain itu, Rekindist akan mengenal lebih dalam profil ketua Rekinnovation sebuah ajang pencarian inovasi , Teguh Arwansyah. -

Society for Ethnomusicology Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology Abstracts Musicianship in Exile: Afghan Refugee Musicians in Finland Facets of the Film Score: Synergy, Psyche, and Studio Lari Aaltonen, University of Tampere Jessica Abbazio, University of Maryland, College Park My presentation deals with the professional Afghan refugee musicians in The study of film music is an emerging area of research in ethnomusicology. Finland. As a displaced music culture, the music of these refugees Seminal publications by Gorbman (1987) and others present the Hollywood immediately raises questions of diaspora and the changes of cultural and film score as narrator, the primary conveyance of the message in the filmic professional identity. I argue that the concepts of displacement and forced image. The synergistic relationship between film and image communicates a migration could function as a key to understanding musicianship on a wider meaning to the viewer that is unintelligible when one element is taken scale. Adelaida Reyes (1999) discusses similar ideas in her book Songs of the without the other. This panel seeks to enrich ethnomusicology by broadening Caged, Songs of the Free. Music and the Vietnamese Refugee Experience. By perspectives on film music in an exploration of films of four diverse types. interacting and conducting interviews with Afghan musicians in Finland, I Existing on a continuum of concrete to abstract, these papers evaluate the have been researching the change of the lives of these music professionals. communicative role of music in relation to filmic image. The first paper The change takes place in a musical environment which is if not hostile, at presents iconic Hollywood Western films from the studio era, assessing the least unresponsive towards their music culture. -

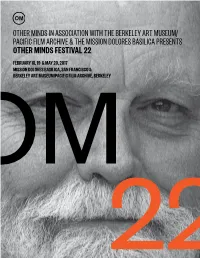

Other Minds in Association with the Berkeley Art

OTHER MINDS IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE BERKELEY ART MUSEUM/ PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE & THE MISSION DOLORES BASILICA PRESENTS OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL 22 FEBRUARY 18, 19 & MAY 20, 2017 MISSION DOLORES BASILICA, SAN FRANCISCO & BERKELEY ART MUSEUM/PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE, BERKELEY 2 O WELCOME FESTIVAL TO OTHER MINDS 22 OF NEW MUSIC The 22nd Other Minds Festival is present- 4 Message from the Artistic Director ed by Other Minds in association with the 8 Lou Harrison Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive & the Mission Dolores Basilica 9 In the Composer’s Words 10 Isang Yun 11 Isang Yun on Composition 12 Concert 1 15 Featured Artists 23 Film Presentation 24 Concert 2 29 Featured Artists 35 Timeline of the Life of Lou Harrison 38 Other Minds Staff Bios 41 About the Festival 42 Festival Supporters: A Gathering of Other Minds 46 About Other Minds This booklet © 2017 Other Minds, All rights reserved 3 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR WELCOME TO A SPECIAL EDITION OF THE OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL— A TRIBUTE TO ONE OF THE MOST GIFTED AND INSPIRING FIGURES IN THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN CLASSICAL MUSIC, LOU HARRISON. This is Harrison’s centennial year—he was born May 14, 1917—and in addition to our own concerts of his music, we have launched a website detailing all the other Harrison fêtes scheduled in his hon- or. We’re pleased to say that there will be many opportunities to hear his music live this year, and you can find them all at otherminds.org/lou100/. Visit there also to find our curated compendium of Internet links to his work online, photographs, videos, films and recordings. -

Lampiran Surat : Nomor : 117/B3.1/Km/2016 Tanggal : 19 Februari 2016

LAMPIRAN SURAT : NOMOR : 117/B3.1/KM/2016 TANGGAL : 19 FEBRUARI 2016 DAFTAR PENERIMA HIBAH PROGRAM KREATIVITAS MAHASISWA (PKM) UNTUK PERGURUAN TINGGI NEGERI TAHUN 2016 NO. NAMA PELAKSANA JUDUL KEGIATAN PERGURUAN TINGGI SKEMA 1 Febry Crunchy On Chocolate : Camilan Cokelat dalam Jar Institut Pertanian Bogor PKMK Nata de Taro - Pemanfaatan Limbah Cair Tepung Talas 2 Fatimatus Zuhro Institut Pertanian Bogor PKMK sebagai Oleh-Oleh Khas Bogor pluma (painted feather accesories) inovasi bisnis bulu 3 Fathya Fiddini Elfajri Institut Pertanian Bogor PKMK unggas handcraft KROTO BESEK: BUDIDAYA KROTO DENGAN SISTEM 4 Tatang Dwi Utomo BESEK SOLUSI MENGHASILKAN SIKLUS PRODUKSI Institut Pertanian Bogor PKMK KROTO YANG CEPAT "Del'covy" Delicious Anchovy: Ikan Teri Medan Ready 5 Hafizh Abdul Aziz Institut Pertanian Bogor PKMK to Eat dengan Varian Rasa Gurinori Snack Daun Singkong: Produk Nori 6 Hayah Afifah Termodifikasi Pangan Lokal Bergizi Institut Pertanian Bogor PKMK O.. I SEE sebagai Sarana Meningkatkan Pengetahuan 7 Rose Anwarni Institut Pertanian Bogor PKMK tentang Laut untuk Dunia International "SARI PERFUME": PARFUM ISLAMI BERBAHAN Muhammad Fikri Abdul 8 MINYAK ATSIRI LOKAL SEBAGAI PRODUK UNGGULAN Institut Pertanian Bogor PKMK Alim INDONESIA ROK TU-IN-ROK SEBAGAI INOVASI USAHA DENGAN 9 Priyanti DESAIN ROK YANG DIGUNAKAN BOLAK-BALIK Institut Pertanian Bogor PKMK MELALUI PEMANFAATAN KAIN PRODUK LOKAL TEH KUKU IPB INOVASI TEH TERBARU BERBAHAN 10 Abdul Salam DASAR KUMIS KUCING DENGAN PEMANIS ALAMI Institut Pertanian Bogor PKMK RENDAH KALORI "WALL-MUSH" Hiasan Edukatif Pertanian Berbasis 11 Lutfi Ilham Pradipta Institut Pertanian Bogor PKMK Budidaya Jamur Agripedia : Usaha Pertanian Berbasis Syariah Sebagai 12 David Anwar Institut Pertanian Bogor PKMK Wadah Inovasi Pertanian yang Solutif dan Inovatif PORL Pomade Rumput Laut Sargassum sp. -

Social and Political Effects of Pop Bali Alternatif on Balinese Society: the Example of "Xxx"1

IJAPS, Vol. 9, No. 1 (January 2013) SOCIAL AND POLITICAL EFFECTS OF POP BALI ALTERNATIF ON BALINESE SOCIETY: THE EXAMPLE OF "XXX"1 Kaori Fushiki2 Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Japan email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This article will clarify how the music genre "Pop Bali Alternatif" affects contemporary Balinese society, both socially and politically. The article focuses on the band "XXX" (Triple X), whose major hit "Puputan Badung" was released in 2006. Recent studies on the "Pop Bali" genre by Balinese researchers have divided it into two main streams: "Pop Bali Konventional" and "Pop Bali Alternatif." In contrast with the former, which is deeply connected with traditional Balinese music, "Pop Bali Alternatif" includes a variety of influences. For this reason, it exerts a powerful social influence, particularly on young people. The activities of "Pop Bali Alternatif" band members, which are covered extensively by mass media, are quickly imitated by their fans. How did this system come about? What kind of albums/songs produced by these bands have influenced the young and to what extent? Finally, how do the historical backgrounds and surroundings of "Pop Bali 1 A number of people and organisations gave me valuable assistance as I wrote this paper. I would like to thank Professor I Gusti Made Sutjaja of Universitas Udanaya (UNUD), Mas Rucitadewi of Bali Post, Made Adnyana of Bali Music Magazine at the time, I Gusti Ngurah Rahman Murthana of Jayagiri production and Otsubo Noriko of Setsunan University. The research for this paper was supported by API Fellowship 2006–2007 and the JSPS Institutional Program for Young Researcher Overseas Visits 2010. -

Dicari Kultur Kehutanan Terbaru

Rimba Indonesia Daftar Isi Volume 54, Desember 2014 04 Revolusi Mental Rimbawan Indonesia 02 Daftar Isi 03 Pengantar Redaksi Sekarang adalah saat yang tepat bagi rimbawan untuk mem 03 Pengasuh Majalah Rimba Indonesia posisikan ulang perannya dalam kehidupan bangsa. Gugatan Artikel Utama gugatan masyarakat terhadap 04 Revolusi Mental Rimbawan Indonesia profesi rimbawan justru harus 08 Revolusi Mental dan Etika Rimbawan dipandang sebagai cambuk untuk kemajuan. Rimbawan harus berubah apabila tidak ingin digilas oleh perubahan jaman, dan kontribusi rimbawan Artikel Pendukung untuk bangsa harus selalu meningkat. 18 Dicari Kultur Kehutanan Terbaru 08 Revolusi Mental dan Etika Rimbawan 21 Memahami dan Mencegah Tindak Kriminal Revolusi mental para rimbawan (Kejahatan) dalam mengem ban tugasnya 26 Rimbawan di Era Dunia yang Sedang Berubah menurut penulis memerlukan (Foresters in A Changing World) Refleksi 50 Tahun pemaha man tentang “etika” dan Fakultas KehutananUniversitas Gadjah Mada menerapkan dalam tanggungjawab profesionalnya sebagai rimbawan. Rimbawan seharusnya mendalami, Sekilas Info memahami Etika Ekologi Dalam ketika mengemban 32 Keberadaan dan Peran Relawan Jaringan tugasnya. Penulis mengajukan Sepuluh Etika Rimbawan, Rimbawan, Lima Tahun Kedepan (2014–2019) untuk kita bahas dan renungkan bersama sama, sebagai 35 Kepemimpinan Mojo bagian dari Revolusi Mental Rimbawan Indonesia. Kalau para rimbawan mampu melaksanakan beberapa etika saja dari 36 Opini: Juru Mudi Kehutanan Pada Kabinet Presiden kesepuluh etika tersebut, Insya Allah, akan terjadi perubahan Jokowi–Jusuf Kalla perubahan sikap mental yang mendasar di tingkat masyarakat 37 Rimbawan Berprestasi dalam Kesehatan (Mencapai di pinggiran hutan yang kehidupannya sangat tergantung dari Usia 80 Tahun Atau Lebih) sumberdaya hutan tersebut. Apalagi kalau mampu menerapkan semua etika tersebut. 38 1001 Khasiat Manfaat Tempe 18 Dicari Kultur Kehutanan Terbaru Apa dan Siapa Tantangan rimbawan dalam peran 41 Ir.