Growth Rings:Communitiesand Trees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Native Plants

- AA GUIDEGUIDE TOTO THETHE NATIVENATIVE PLANTS,PLANTS, NATURALNATURAL PLANTPLANT COMMUNITIESCOMMUNITIES ANDAND THETHE EXOTICEXOTIC ANDAND INVASIVEINVASIVE SPECIESSPECIES OFOF EASTEAST HAMPTONHAMPTON TOWNTOWN EAST HAMPTON TOWN Natural Resources Department TableTable ofof Contents:Contents: Spotted Beebalm (Monarda punctata) Narrative: Pages 1-17 Quick Reference Max Clearing Table: Page 18 Map: East Hampton Native Plant Habitats Map TABS: East Hampton Plant Habitats (1-12); Wetlands flora (13-15): 1. Outer Dunes Plant Spacing 2. Bay Bluffs 3. Amagansett Inner Dunes (AID) 4. Tidal Marsh (TM) Table: A 5. Montauk Mesic Forest (MMF) 6. Montauk Moorland (MM) guideline for the 7. North of Moraine Coastal Deciduous (NMCD) 8. Morainal Deciduous (MD) 9. Pine Barrens or Pitch Pine Oak Forest (PB) (PPO) number of 10. Montauk Grasslands (MG) 11. Northwest Woods (NWW) plants needed 12. Old Fields 13. Freshwater Wetlands 14. Brackish Wetlands and Buffer for an area: 15. East Hampton Wetland Flora by Type Page 19 Native Plants-Resistance to Deer Damage: Pages 20-21 Local Native Plant Landscapers, Arborists, Native Plant Growers and Suppliers: Pages 22-23 Exotic and Invasive Species: Pages 24-33 Native Wildflower Pictures: Pages 34-45 Samdplain Gerardia (Agalinas acuta) Introduction to our native landscape What is a native plant? Native plants are plants that are indigenous to a particular area or region. In North America we are referring to the flora that existed in an area or region before European settlement. Native plants occur within specific plant communities that vary in species composition depending on the habitat in which they are found. A few examples of habitats are tidal wetlands, woodlands, meadows and dunelands. -

Native Seed Collection Methods6

G UIDELINES NATIVE SEED COLLECTION METHODS6 Seed collection is an activity that can be can be used. It stresses the importance of undertaken by people of all ages and skill preparation and planning for seed collection levels, and can be very satisfying. Any and the need to collect mature seed. robust person with some basic knowledge We assume that you already have some and equipment can easily and inexpensively experience of collecting native plant seed collect native seeds. For those involved in and a basic knowledge of how to accurately community revegetation projects, seed identify flora in the field, understand plant collection is a great way to learn more reproduction, seed biology and ecology, and about the plants being used and gives when and where to collect seed. You can communities greater ownership of all stages find out more about these subjects from in the revegetation cycle. various sources, such as standard botanical However, collecting native seed on a larger references, textbooks, field keys and local scale (for example, in every season and for a knowledge. There are also other guidelines wide range of plants) is a demanding from FloraBank that provide important endeavour. Making such an activity cost- information about seed collection. They effective adds an extra element of difficulty. include: There may be many natural, logistical and • Guideline 4: Keeping records about native bureaucratic hurdles to overcome – one seed collections could spend a lifetime learning to collect native seed efficiently in one region; only a • Guideline 5: Seed collection from woody handful of people can do it for the plants of plants for local revegetation, and their whole State, or of Australia. -

STORMWATCH: TEAM ACHILLES #20 "NEW BEGINNINGS" by Micah Ian Wright First Draft 12/17/03

STORMWATCH: TEAM ACHILLES #20 "NEW BEGINNINGS" by Micah Ian Wright First Draft 12/17/03 Wildstorm Comics 888 Prospect Avenue La Jolla, CA 92037 StormWatch: Team Achilles #20 “Meet the New Boss: Same As The Old Boss” Written by Micah Ian Wright First Draft December 17, 2003 PAGE 1 PANEL ONE Widescreen establishing shot of the exterior of the United Nations Palais Des Nations building (see reference page). BORDERLESS LOCATION CAPTION United Nations Palais Des Nations Geneva, Switzerland PANEL TWO Inside the building in the long hallway which runs around the building (see reference page). Several diplomats from several continents and dressed in suits or ethnic clothing styles stare in shock as Ben Santini walks out of a glowing Project Entry Circle, wearing his US Army Military Uniform, speaking into a cel phone.. SANTINI Okay, Tefibi, I’m inside. Now what? TEFIBI (CEL PHONE) Turn East. The Director-General’s office is at the center of the hallway. TEFIBI (CEL PHONE) Before you do anything else, though, put the earpatch on the bone directly behind your ear. PANEL THREE C/U as Santini puts a small flesh-colored sticky bandage behind his right ear. It looks like one a small round band-aid, but instead of a bandage in the center, there is a thin layer of electronics. SANTINI It’s on. TEFIBI (CEL PHONE) Okay, SW One is going to say something into your earpatch. EARBUD CAPTION (this should be a TINY caption, colored the same color as Ben Santini’s Radio Talk captions, it’s just an indicator that information is passing to Santini) .. -

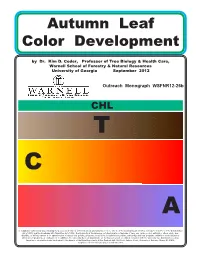

Fall Color Pub 12-26

Autumn Leaf Color Development by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care, Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources University of Georgia September 2012 Outreach Monograph WSFNR12-26b CHL T C red A In compliance with federal law, including the provisions of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Sections 503 and 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the University of Georgia does not discriminate on the basis of race, sex, religion, color, national or ethnic origin, age, disability, or military service in its administration of educational policies, programs, or activities; its admissions policies; scholarship and loan programs; athletic or other University- administered programs; or employment. In addition, the University does not discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation consistent with the University non-discrimination policy. Inquiries or complaints should be directed to the director of the Equal Opportunity Office, Peabody Hall, 290 South Jackson Street, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602. Telephone 706-542-7912 (V/TDD). Fax 706-542-2822. Autumn Leaf Color Development by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care Trees have many strategies for life. Some grow fast and die young, others grow slow and live a long time. Some trees colonize new soils and new space, while other trees survive and thrive in the midst of old forests. A number of trees invest in leaves which survive several growing seasons, while other trees grow new leaves every growing season. One of the most intriguing and beautiful result of tree life strategies is autumn leaf coloration among deciduous trees. -

The Magazine of the Arnold Arboretum VOLUME 77 • NUMBER 4

The Magazine of the Arnold Arboretum VOLUME 77 • NUMBER 4 The Magazine of the Arnold Arboretum VOLUME 77 • NUMBER 4 • 2020 CONTENTS Arnoldia (ISSN 0004–2633; USPS 866–100) 2 Uncommon Gardens is published quarterly by the Arnold Arboretum Ben Goulet-Scott of Harvard University. Periodicals postage paid at Boston, Massachusetts. 6 Revisiting the Mystery of the Bartram Oak Subscriptions are $20.00 per calendar year Andrew Crowl, Ed Bruno, Andrew L. Hipp, domestic, $25.00 foreign, payable in advance. and Paul Manos Remittances may be made in U.S. dollars, by 12 Collector on a Grand Scale: The Horticultural check drawn on a U.S. bank; by international Visions of Henry Francis du Pont money order; or by Visa, Mastercard, or American Express. Send orders, remittances, requests to Carter Wilkie purchase back issues, change-of-address notices, 24 Eternal Forests: The Veneration of and all other subscription-related communica- Old Trees in Japan tions to Circulation Manager, Arnoldia, Arnold Arboretum, 125 Arborway, Boston, MA 02130- Glenn Moore and Cassandra Atherton 3500. Telephone 617.524.1718; fax 617.524.1418; 32 Each Year in the Forest: Spring e-mail [email protected] Andrew L. Hipp Arnold Arboretum members receive a subscrip- Illustrated by Rachel D. Davis tion to Arnoldia as a membership benefit. To become a member or receive more information, 41 How to See Urban Plants please call Wendy Krauss at 617.384.5766 or Jonathan Damery email [email protected] 44 Spring is the New Fall Postmaster: Send address changes to Kristel Schoonderwoerd Arnoldia Circulation Manager The Arnold Arboretum Front and back cover: Sargent cherry (Prunus sargentii) 125 Arborway was named, in 1908, in honor of Charles Sprague Sargent, Boston, MA 02130–3500 the first director of the Arnold Arboretum. -

Extraordinary Encounters: an Encyclopedia of Extraterrestrials and Otherworldly Beings

EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS An Encyclopedia of Extraterrestrials and Otherworldly Beings Jerome Clark B Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright © 2000 by Jerome Clark All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Clark, Jerome. Extraordinary encounters : an encyclopedia of extraterrestrials and otherworldly beings / Jerome Clark. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57607-249-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)—ISBN 1-57607-379-3 (e-book) 1. Human-alien encounters—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BF2050.C57 2000 001.942'03—dc21 00-011350 CIP 0605040302010010987654321 ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper I. Manufactured in the United States of America. To Dakota Dave Hull and John Sherman, for the many years of friendship, laughs, and—always—good music Contents Introduction, xi EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS: AN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF EXTRATERRESTRIALS AND OTHERWORLDLY BEINGS A, 1 Angel of the Dark, 22 Abductions by UFOs, 1 Angelucci, Orfeo (1912–1993), 22 Abraham, 7 Anoah, 23 Abram, 7 Anthon, 24 Adama, 7 Antron, 24 Adamski, George (1891–1965), 8 Anunnaki, 24 Aenstrians, 10 Apol, Mr., 25 -

Rethinking Webcomics: Webcomics As a Screen Based Medium

Dennis Kogel Digital Culture Department of Art and Culture Studies 16.01.2013 MA Thesis Rethinking Webcomics: Webcomics as a Screen Based Medium JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO Tiedekunta – Faculty Laitos – Department Humanities Art and Culture Studies Tekijä – Author Dennis Kogel Työn nimi – Title Rethinking Webcomics: Webcomics as a Screen Based Medium Oppiaine – Subject Työn laji – Level Digital Culture MA Thesis Aika – Month and year Sivumäärä – Number of pages January 2013 91 pages Tiivistelmä – Abstract So far, webcomics, or online comics, have been discussed mostly in terms of ideologies of the Internet such as participatory culture or Open Source. Not much thought, however, has been given to webcomics as a new way of making comics that need to be studied in their own right. In this thesis a diverse set of webcomics such as Questionable Content, A Softer World and FreakAngels is analyzed using a combination of N. Katherine Hayles’ Media Specific Analysis (MSA) and the neo-semiotics of comics by Thierry Groensteen. By contrasting print- and web editions of webcomics, as well as looking at web-only webcomics and their methods for structuring and creating stories, this thesis shows that webcomics use the language of comics but build upon it through the technologies of the Web. Far from more sensationalist claims by scholars such as Scott McCloud about webcomics as the future of the comic as a medium, this thesis shows that webcomics need to be understood as a new form of comics that is both constrained and enhanced by Web technologies. Although this thesis cannot be viewed as a complete analysis of the whole of webcomics, it can be used as a starting point for further research in the field and as a showcase of how more traditional areas of academic research such as comic studies can benefit from theories of digital culture. -

Leaves of Grass

Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman AN ELECTRONIC CLASSICS SERIES PUBLICATION Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman is a publication of The Electronic Classics Series. This Portable Document file is furnished free and without any charge of any kind. Any person using this document file, for any pur- pose, and in any way does so at his or her own risk. Neither the Pennsylvania State University nor Jim Manis, Editor, nor anyone associated with the Pennsylvania State University assumes any responsibility for the material contained within the document or for the file as an electronic transmission, in any way. Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman, The Electronic Clas- sics Series, Jim Manis, Editor, PSU-Hazleton, Hazleton, PA 18202 is a Portable Document File produced as part of an ongoing publication project to bring classical works of literature, in English, to free and easy access of those wishing to make use of them. Jim Manis is a faculty member of the English Depart- ment of The Pennsylvania State University. This page and any preceding page(s) are restricted by copyright. The text of the following pages are not copyrighted within the United States; however, the fonts used may be. Cover Design: Jim Manis; image: Walt Whitman, age 37, frontispiece to Leaves of Grass, Fulton St., Brooklyn, N.Y., steel engraving by Samuel Hollyer from a lost da- guerreotype by Gabriel Harrison. Copyright © 2007 - 2013 The Pennsylvania State University is an equal opportunity university. Walt Whitman Contents LEAVES OF GRASS ............................................................... 13 BOOK I. INSCRIPTIONS..................................................... 14 One’s-Self I Sing .......................................................................................... 14 As I Ponder’d in Silence............................................................................... -

Urban Forest Bibliography

Urban Forestry Bibliography Created by the Forest Service Northern Research Station February 26, 2008 1969. "Colourful Street Trees." Nature 221:10-&. 1987. "DE-ICING WITH SALT CAN HARM TREES." Pp. C.7 in New York Times. 1993. "Urban arborcide." Environment 35:21. 1995. "Proceedings of the 1995 Watershed Management Symposium." in Watershed Management Symposium - Proceedings. 1998. "Cooling hot cities with trees." Futurist 32:13-13. 1998. "Tree Guard 5 - latest from Netlon." Forestry and British Timber:36. 2000. "ANOTHER FINE MESH!" Forestry and British Timber:24. 2000. "Nortech Sells Tree Guard Product for $850,000." PR Newswire:1. 2000. "One Texas town learns the value of its trees." American City & County 115:4. 2000. "Texas City relies on tree canopy to reduce runoff." Civil Engineering 70:18-18. 2001. "Proceedings: IEEE 2001 International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium." in International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), vol. 3. 2001. "Protective Gear for New York City Trees." American Forests 107:18. 2001. "Trees May Not Be So Green!" Hart's European Fuels News 5:1. 2002. "Fed assessment forecasts strong timber inventories, more plantations." Timber Harvesting 50:7. 2002. "Proceedings: 2002 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. 24th Canadian Symposium on Remote Sensing." in International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), vol. 3. 2002. "Toledo, Ohio - Recycled rubber mulch used on rooftop garden." Biocycle 43:21-21. 2002. "TREE SHELTERS: Lower lining life." Forestry and British Timber:58. 2003. "The forest lawn siphon project - An HDD success story." Geodrilling International 11:12-14. 2003. "Trenchless technology." Public Works 134:28-29. -

Rhetorical Transformations of Trees in Medieval England: From

RHETORICAL TRANSFORMATIONS OF TREES IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND: FROM MATERIAL CULTURE TO LITERARY REPRESENTATION Jodi Elisabeth Grimes, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2008 APPROVED: Robert K. Upchurch, Major Professor Nicole D. Smith, Committee Member Jacqueline Vanhoutte, Committee Member David Holdeman, Chair of Department of English Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Grimes, Jodi Elisabeth. Rhetorical Transformations of Trees in Medieval England: From Material Culture to Literary Representation. Doctor of Philosophy (English), December 2008, 212 pp., 7 illustrations, bibliography, 301 titles. Literary texts of medieval England feature trees as essential to the individual and communal identity as it intersects with nature, and the compelling qualities and organic processes associated with trees help vernacular writers interrogate the changing nature of this character. The early depiction of trees demonstrates an intimacy with nature that wanes after the tenth-century monastic revival, when the representation of trees as living, physical entities shifts toward their portrayal as allegorical vehicles for the Church’s didactic use. With the emergence of new social categories in the late Middle Ages, the rhetoric of trees moves beyond what it means to forge a Christian identity to consider the role of a ruler and his subjects, the relationship between humans and nature, and the place of women in society. Taking as its fundamental premise that people in wooded regions develop a deep-rooted connection to trees, this dissertation connects medieval culture and the physical world to consider the variety of ways in which Anglo-Saxon and post-Norman vernacular manuscripts depict trees. -

2010Sdccexclusiveschecklist.Pdf

258 WEST AUTHENTIC SIGNATURES (Items @ SUICIDE CLOTHING Booth J08) __ Glee's Heather Morris Autographed Trading Card $25 - 258 pieces __ Supernatural’s Misha Collins Autographed Trading Card $35 - 400 pieces __ True Blood’s Brit Morgan Autographed Trading Card $15 - 500 pieces __ True Blood’s Kristin Bauer Autographed Trading Card $15 - 500 pieces __ True Blood’s Patrick Gallagher Autographed Trading Card $10 - 500 pieces 2000 AD Booth 2301 __ Judge Dredd T-Shirt $30 - 150 pieces ACME ARCHIVES Booth 5429 __ Star Wars Character Key Chewbacca Print $35 - 750 pieces __ HALO: Reach "Evolutions" Green Variant Print $75 - 100 pieces APPLEHEAD FACTORY Booth 4923 __ Abnormal Cyrus Comic Con Apron Edition $20 - 150 pieces – comes with Monster Mouth Rita Mortis keychain and pin ARCANA COMIC STUDIOS Booth 2415 __ The Citizens #1 Comic Book Limited to 250 pieces ARTBOX ENTERTAINMENT Booth 2335 __ Harry Potter Trading Cards ASPEN MLT INC. Booth 2321 __ Fathom: Blue Descent #1 Comic Book $5 - 500 pieces __ The Scourge #0 Comic Book $5 - 1,000 pieces AVATAR PRESS Booth 2701 __ Alan Moore Signed Light of Thy Countenance Leather Hardcover Comic Book $65 - 350 pieces __ Alan Moore's Neonomicon #1 Comic Book $4 - 1,500 pieces __ Alan Moore's Neonomicon Hornbook Artifact Edition Comic Book $10 - 500 pieces __ Anna Mercury Vol 1 Signed Leather Hardcover Comic Book $50 - 350 pieces __ Crossed: Family Values #2 Comic Book $6 - 750 pieces __ Crossed Mask Free while supplies last - 2,000 pieces __ Fevre Dreams #2 Comic Book $4 - 1,000 pieces __ Freakangels 2010 -

Hunter S. Thompson, Transmetropolitan, and the Evolution from Author To

Hunter S. Thompson, Transmetropolitan, and the Evolution from Author to Character By Ashlee Amanda Nelson A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Literature Victoria University of Wellington 2014 2 Table of Contents Figures Page 3 Acknowledgements Page 4 Abstract Page 5 Introduction Page 7 Chapter One Page 12 Chapter Two Page 38 Chapter Three Page 68 Conclusion Page 95 Works Cited Page 98 3 Figures Fig. 1 p. 41 Spider Jerusalem’s car (Transmetropolitan 1:10) Fig. 2 p. 43 Spider Jerusalem (Transmetropolitan 1:4) and Hunter Thompson (Ancient Gonzo Wisdom) Fig. 3 p. 43 Spider Jerusalem (Transmetropolitan 1:28) and Hunter Thompson as drawn by Ralph Steadman in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (14) Fig. 4 p. 45 Mitchell Royce (Transmetropolitan 1:20) and Jann Wenner (Bazilian) Fig. 5 p. 50 Spider’s articles (Transmetropolitan 4:40) Fig. 6 p. 53 Spider acting out an imaginary conversation (Transmetropolitan 5:12) Fig. 7 p. 57 “The Beast” (Transmetropolitan 1:94) Fig. 8 p. 60 The “The Smiler” (Transmetropolitan 3:45) Fig. 9 p. 82 Spider’s article (Transmetropolitan 1:65) Fig. 10 p. 83 Spider’s journalism (Transmetropolitan 3:53) Fig. 11 p. 84 Fonts and speech box styles (Transmetropolitan 5:63-64) Fig. 12 p. 86 Spider’s interviews with the homeless (Transmetropolitan 7:106) Fig. 13 p. 87 Spider’s article juxtaposed against him writing it (Transmetropolitan 7:109) Fig. 14 p. 88 Article by Spider (Transmetropolitan 5:38) Fig. 15 p.