The Finer Worlds of Warren Ellis William James Allred University of Arkansas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Charismatic Leadership and Cultural Legacy of Stan Lee

REINVENTING THE AMERICAN SUPERHERO: THE CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP AND CULTURAL LEGACY OF STAN LEE Hazel Homer-Wambeam Junior Individual Documentary Process Paper: 499 Words !1 “A different house of worship A different color skin A piece of land that’s coveted And the drums of war begin.” -Stan Lee, 1970 THESIS As the comic book industry was collapsing during the 1950s and 60s, Stan Lee utilized his charismatic leadership style to reinvent and revive the superhero phenomenon. By leading the industry into the “Marvel Age,” Lee has left a multilayered legacy. Examples of this include raising awareness of social issues, shaping contemporary pop-culture, teaching literacy, giving people hope and self-confidence in the face of adversity, and leaving behind a multibillion dollar industry that employs thousands of people. TOPIC I was inspired to learn about Stan Lee after watching my first Marvel movie last spring. I was never interested in superheroes before this project, but now I have become an expert on the history of Marvel and have a new found love for the genre. Stan Lee’s entire personal collection is archived at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center in my hometown. It contains 196 boxes of interviews, correspondence, original manuscripts, photos and comics from the 1920s to today. This was an amazing opportunity to obtain primary resources. !2 RESEARCH My most important primary resource was the phone interview I conducted with Stan Lee himself, now 92 years old. It was a rare opportunity that few people have had, and quite an honor! I use clips of Lee’s answers in my documentary. -

Toys and Action Figures in Stock

Description Price 1966 Batman Tv Series To the B $29.99 3d Puzzle Dump truck $9.99 3d Puzzle Penguin $4.49 3d Puzzle Pirate ship $24.99 Ajani Goldmane Action Figure $26.99 Alice Ttlg Hatter Vinimate (C: $4.99 Alice Ttlg Select Af Asst (C: $14.99 Arrow Oliver Queen & Totem Af $24.99 Arrow Tv Starling City Police $24.99 Assassins Creed S1 Hornigold $18.99 Attack On Titan Capsule Toys S $3.99 Avengers 6in Af W/Infinity Sto $12.99 Avengers Aou 12in Titan Hero C $14.99 Avengers Endgame Captain Ameri $34.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Iron $14.99 Avengers Infinite Grim Reaper $14.99 Avengers Infinite Hyperion $14.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Axe Cop $15.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Dr Doo Doo $12.99 Batman Arkham City Ser 3 Ras A $21.99 Batman Arkham Knight Man Bat A $19.99 Batman Batmobile Kit (C: 1-1-3 $9.95 Batman Batmobile Super Dough D $8.99 Batman Black & White Blind Bag $5.99 Batman Black and White Af Batm $24.99 Batman Black and White Af Hush $24.99 Batman Mixed Loose Figures $3.99 Batman Unlimited 6-In New 52 B $23.99 Captain Action Thor Dlx Costum $39.95 Captain Action's Dr. Evil $19.99 Cartoon Network Titans Mini Fi $5.99 Classic Godzilla Mini Fig 24pc $5.99 Create Your Own Comic Hero Px $4.99 Creepy Freaks Figure $0.99 DC 4in Arkham City Batman $14.99 Dc Batman Loose Figures $7.99 DC Comics Aquaman Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Batman Dark Knight B $6.99 DC Comics Batman Wood Figure $11.99 DC Comics Green Arrow Vinimate $9.99 DC Comics Shazam Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Super -

BATMAN Vs SUPERMAN What Would Superman Drive, What Should Batman Drive and Where Could Wonder Woman Store Her Outfit?

WIN A PULSAR BRUCE WAYNE’S JEEP WATCH PEUGEOT ADD FUEL OFFERS WORTH DUCHESS OF CAMBRIDGE PLAYS TENNIS £145 SHORTLISTED FOR NEWSPRESS MAGAZINE OF THE YEAR BATMAN vs SUPERMAN What would Superman drive, what should Batman drive and where could Wonder Woman store her outfit? Your magazine featuring the stars, their cars and more... freecarmag.co.uk 1 FUELLED BY FUN This ISSUEweek 30 / 2016 Batman vs Superman: Dawn of Justice. We don’t understand why there are a couple of superheroes slugging it out like a wrestling bout, with Wonder Woman watching disapprovingly. However, we are looking forward to making sense of it all very soon at the local multiplex. We’ve got a superhero of our own Free Car Mag, or possibly Margaret, but we are too frightened to call her that. Well she’s more than qualified to tell other superheroes and even super villains what to drive. There is still time to win yourself a brilliant Pulsar watch. All you have to do is sign up to get notification of the latest issue. If you have already signed up, then you are already in with a chance. Tell all your friends and family, because we don’t spam you with nonsense, or pass your details on. We are good like that. 4 News Events Celebs – Made in Chelsea We are also doing very well at the moment. Shortlisted as and Duchess of Cambridge Consumer Magazine and Editor of the Year in the Newspress 6 Batman vs Superman Awards after only being around for a year, it has taken a real 8 Supercars for Superheroes superhuman effort I can tell you. -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

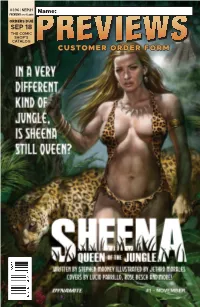

Customer Order Form

#396 | SEP21 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Sep21 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:51 AM GTM_Previews_ROF.indd 1 8/5/2021 8:54:18 AM PREMIER COMICS NEWBURN #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 A THING CALLED TRUTH #1 IMAGE COMICS 38 JOY OPERATIONS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 84 HELLBOY: THE BONES OF GIANTS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 86 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMPOSTER SYNDROME #1 IDW PUBLISHING 114 SHEENA, QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 132 POWER RANGERS UNIVERSE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 184 HULK #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-4 Sep21 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:11 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Guillem March’s Laura #1 l ABLAZE The Heathens #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Fathom: The Core #1 l ASPEN COMICS Watch Dogs: Legion #1 l BEHEMOTH ENTERTAINMENT 1 Tuki Volume 1 GN l CARTOON BOOKS Mutiny Magazine #1 l FAIRSQUARE COMICS Lure HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 The Overstreet Guide to Lost Universes SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Carbon & Silicon l MAGNETIC PRESS Petrograd TP l ONI PRESS Dreadnoughts: Breaking Ground TP l REBELLION / 2000AD Doctor Who: Empire of the Wolf #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2029 #9 l TITAN COMICS The Man Who Shot Chris Kyle: An American Legend HC l TITAN COMICS Star Trek Explorer Magazine #1 l TITAN COMICS John Severin: Two-Fisted Comic Book Artist HC l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING The Harbinger #2 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Lunar Room #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 My Hero Academia: Ultra Analysis Character Guide SC l VIZ MEDIA Aidalro Illustrations: Toilet-Bound Hanako Kun Ark Book SC l YEN PRESS Rent-A-(Really Shy!)-Girlfriend Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Lupin III (Lupin The 3rd): Greatest Heists--The Classic Manga Collection HC l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT APPAREL 2 Halloween: “Can’t Kill the Boogeyman” T-Shirt l HORROR Trese Vol. -

Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko

Law Text Culture Volume 16 Justice Framed: Law in Comics and Graphic Novels Article 10 2012 Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Swinburne University of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Bainbridge, Jason, Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko, Law Text Culture, 16, 2012, 217-242. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Abstract The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. This relationship has also informed superhero comics themselves – going all the way back to Superman’s debut in Action Comics 1 (June 1938). As DC President Paul Levitz says of the development of the superhero: ‘There was an enormous desire to see social justice, a rectifying of corruption. Superman was a fulfillment of a pent-up passion for the heroic solution’ (quoted in Poniewozik 2002: 57). This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Spider-Man, The Question and the Meta-Zone: Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Bainbridge Introduction1 The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. -

Sloane Drayson Knigge Comic Inventory (Without

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Number Donor Box # 1,000,000 DC One Million 80-Page Giant DC NA NA 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 A Moment of Silence Marvel Bill Jemas Mark Bagley 2002 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alex Ross Millennium Edition Wizard Various Various 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Open Space Marvel Comics Lawrence Watt-Evans Alex Ross 1999 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alf Marvel Comics Michael Gallagher Dave Manak 1990 33 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 2 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 3 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 4 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 5 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 6 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Aphrodite IX Top Cow Productions David Wohl and Dave Finch Dave Finch 2000 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 600 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 601 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 602 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 603 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 -

Released 19Th August 2020 BOOM!

Released 19th August 2020 BOOM! STUDIOS JAN201335 ANGEL SEASON 11 LIBRARY ED HC APR201364 FAITHLESS II #3 CVR A LLOVET APR201365 FAITHLESS II #3 CVR B EROTICA CONNECTING VAR JUN200787 FIREFLY #19 CVR A MAIN ASPINALL JUN200788 FIREFLY #19 CVR B KAMBADAIS VAR FEB201290 GO GO POWER RANGERS TP VOL 07 APR201373 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL AGE RESISTANCE #10 CVR A FINDEN APR201374 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL AGE RESISTANCE #10 CVR B MATTHEWS CO APR201371 ONCE & FUTURE #10 FEB201340 OVER GARDEN WALL SOULFUL SYMPHONIES TP JUN200764 POWER RANGERS DRAKKON NEW DAWN #1 CVR A MAIN SECRET JUN200767 POWER RANGERS DRAKKON NEW DAWN #1 FOIL VAR JUN208619 POWER RANGERS RANGER SLAYER #1 (2ND PTG) MAR201359 QUOTABLE GIANT DAYS GN JUN208620 SOMETHING IS KILLING CHILDREN #7 (2ND PTG) DARK HORSE COMICS APR200392 ART OF DRAGON PRINCE HC JAN200399 CYBERPUNK 2077 KITSCH PUZZLE JAN200400 CYBERPUNK 2077 NEOKITSCH PUZZLE JUN200310 DRAGON AGE BLUE WRAITH HC DC COMICS MAR200619 BATMAN BY GRANT MORRISON OMNIBUS HC VOL 03 OCT190663 GREEN ARROW LONGBOW HUNTERS OMNIBUS HC VOL 01 DYNAMITE APR201139 BETTIE PAGE #1 KANO LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201140 BETTIE PAGE #1 LINSNER LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201138 BETTIE PAGE #1 YOON LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201266 GEORGE RR MARTIN A CLASH OF KINGS #6 CVR A MILLER APR201267 GEORGE RR MARTIN A CLASH OF KINGS #6 CVR B RUBI APR201154 GREEN HORNET #1 JOHNSON LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201153 GREEN HORNET #1 WEEKS LTD VIRGIN VAR MAR201221 JAMES BOND #6 RICHARDSON LTD VIRGIN CVR MAR201231 KILLING RED SONJA #3 CVR A WARD MAR201232 KILLING RED SONJA #3 CVR B GEDEON HOMAGE APR201283 -

Elementary, My Dear Readers

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Elementary, My Dear Readers NCIS (which stands for Naval Criminal Investigative Service) is an extremely popular “police procedural” television drama that has spun off as a New Orleans series. NCIS: New Orleans, which airs Tuesday nights on CBS, is set in the Crescent City and it would be highly unusual if you haven’t seen the show filming around town. It premiered on September 23, 2014. The episodes revolve around a fictional team of agents led by Special Agent Dwayne Cassius “King” Pride, Special Agent Christopher LaSalle, and Special Agent Meredith Brody. They handle criminal investigations involving the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps. If the NCIS team seems to be everywhere you look these days, allow yourself to travel back in literary time and imagine another famous detective team present all around you. Even if their bailiwick was late Victorian England, I seem to feel their presence all around this historic city. Perhaps you will, too. Arthur Conan Doyle penned his first Sherlock Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, in novel form in 1886 at the age of 27. In it Holmes expounded: “Criminal cases are continually hinging upon that one point. A man is suspected of a crime months perhaps after it has been committed. His linen or clothes are examined and brownish stains discovered upon them. Are they blood stains, or mud stains, or rust stains, or fruit stains, or what are they? That is a question which has puzzled many an expert, and why? Because there was no reliable test. -

Mapping Black Ash Dominated Stands Using Geospatial and Forest Inventory Data in Northern Minnesota, USA Peder S

892 ARTICLE Mapping black ash dominated stands using geospatial and forest inventory data in northern Minnesota, USA Peder S. Engelstad, Michael J. Falkowski, Anthony W. D’Amato, Robert A. Slesak, Brian J. Palik, Grant M. Domke, and Matthew B. Russell Abstract: Emerald ash borer (EAB; Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire, 1888) has been a persistent disturbance for ash forests in the United States since 2002. Of particular concern is the impact that EAB will have on the ecosystem functioning of wetlands dominated by black ash (Fraxinus nigra Marsh.). In preparation, forest managers need reliable and complete maps of black ash dominated stands. Traditionally, forest survey data from the United States Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) Program have provided rigorous measures of tree species at large spatial extents but are limited when providing estimates for smaller management units (e.g., stands). Fortunately, geospatial data can extend forest survey information by generating predictions of forest attributes at scales finer than those of the FIA sampling grid. In this study, geospatial data were integrated with FIA data in a randomForest model to estimate and map black ash dominated stands in northern Minnesota in the United States. The model produced low error rates (overall error = 14.5%; area under the curve (AUC) = 0.92) and was strongly informed by predictors from soil saturation and phenology. These results improve upon FIA-based spatial estimates at national extents by providing forest managers with accurate, fine-scale maps (30 m spatial resolution) of black ash stand dominance that could ultimately support landscape-level EAB risk and vulnerability assessments. Key words: compound topographic index (CTI), remote sensing, black ash, emerald ash borer, forest inventory. -

The Authority: Earth Inferno and Other Stories V. 3 Free

FREE THE AUTHORITY: EARTH INFERNO AND OTHER STORIES V. 3 PDF Mark Millar,Frank Quitely,Chris Weston | 160 pages | 01 Aug 2002 | DC Comics | 9781563898549 | English | United States Earth Inferno for sale online | eBay This article is a list of story arcs for the Wildstorm comic book The Authority presented in chronological order of release. The Authority make their first public appearance to stop Kaizen Gamorraan old enemy of Stormwatchwho wants to take advantage of Stormwatch's breakup to take revenge upon the world. To do this he uses engineered supersoldiers to destroy first Moscow and then part of London. The Authority does not manage to stop the attack on London, then predicts the third and final attack in Los Angeles which is averted with heavy civilian casualties. Midnighter uses the Carrier to destroy the superhuman clone factory on Gamorra's island. The Authority have to stop an invasion by a parallel Earth, specifically a parallel Britain called Sliding Albion. As it turns out, Jenny Sparks has met them before when their The Authority: Earth Inferno and Other Stories v. 3 first appeared in Sliding Albion is a world where open contact between aliens the blues and humans during the 16th century led to interbreeding and an imperialist culture similar to the Victorian British Empire. After the Authority repel the initial wave of attacks, Jenny takes the Carrier to the Sliding Albion universe where they destroy London and Italy and what's left of the blues' regime along with it. In an all-frequencies message, she tells the people to take advantage of the second chance and "We are the Authority. -

Apollo Investment Corporation (“AINV” Or the “Company”) for the Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2020

2020 ANNUAL REPORT Dear Fellow Shareholders, We are pleased to present you with the annual report for Apollo Investment Corporation (“AINV” or the “Company”) for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2020. As we write this year's letter, the world is facing both a significant health and economic crisis due to the outbreak of the novel coronavirus (“COVID-19”, “coronavirus”, or “pandemic”). We hope this letter finds you safe and in good health. In our annual shareholder letters, we typically review our results for the year and provide our outlook for the next fiscal year. In this year’s letter, we will also focus on how AINV was positioned entering this challenging period, and how we are navigating the current environment. First and foremost, on behalf of everyone at AINV, we want to express our appreciation to all those who are working tirelessly to keep us safe and maintain essential services. We offer our deepest sympathy to all those who have been affected by the coronavirus. Our priority continues to be the health and well-being of our stakeholders and the employees of the Company’s Investment Adviser, Apollo Investment Management, L.P., an affiliate of Apollo Global Management, Inc., (together with its affiliates, “Apollo Global”). Apollo has fully transitioned to a remote work environment while ensuring full business continuity. A Review of Fiscal Year 2020 Looking back at fiscal year 2020, we continued to make significant progress executing our de-risking investment strategy to prepare for potential headwinds, if not an economic downturn such as the one we are currently experiencing.