Rethinking Webcomics: Webcomics As a Screen Based Medium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JKA918 Manga Studies (JB, VT2019) (1) Studying Manga: Introduction to the Research Field Inside and Outside of Japan JB (2007)

JKA918 Manga Studies (JB, VT2019) (1) Studying manga: Introduction to the research field inside and outside of Japan JB (2007), “Considering Manga Discourse: Location, Ambiguity, Historicity”. In Japanese Visual Culture, edited by Mark MacWilliams, pp. 351-369. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe [e-book]; JB (2016), Chapter 8 “Manga, which Manga? Publication Formats, Genres, Users,” in Japanese Civilization in the 21st Century. New York: Nova Science Publishers, ed. Andrew Targowski et al., pp. 121-133; Kacsuk, Zoltan (2018), “Re-Examining the ‘What is Manga’ Problematic: The Tension and Interrelationship between the ‘Style’ Versus ‘Made in Japan’ Positions,” Arts 7, 26; https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0752/7/3/26 (2) + (3) Archiving popular media: Museum, database, commons (incl. sympos. Archiving Anime) JB (2012), “Manga x Museum in Contemporary Japan,” Manhwa, Manga, Manhua: East Asian Comics Studies, Leipzig UP, pp. 141-150; Azuma, Hiroki ((2009), Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals, UP of Minnesota; ibid. (2012), “Database Animals,” in Ito, Mizuko, ed., Fandom Unbound: Otaku Culture in a Connected World, Yale UP, pp. 30–67. [e-book] (4) Manga as graphic narrative 1: Tezuka Osamu’s departure from the ‘picture story’ Pre- reading: ex. Shimada Keizō, “The Adventures of Dankichi,” in Reading Colonial Japan: Text, Context, and Critique, ed. Michele Mason & Helen Lee, Stanford UP, 2012, pp. 243-270. [e-book]; Natsume, Fusanosuke (2013). “Where Is Tezuka?: A Theory of Manga Expression,” Mechademia vol. 8, pp. 89-107 [e-journal]; [Clarke, M.J. (2017), “Fluidity of figure and space in Osamu Tezuka’s Ode to Kirihito,” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 26pp. -

Doing Social Sciences Via Comics and Graphic Novels. an Introduction

Re-formats: Envisioning Sociology – peer-reviewed Sociologica. V.15 N.1 (2021) https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1971-8853/12773 ISSN 1971-8853 Doing Social Sciences Via Comics and Graphic Novels. An Introduction Eduardo Barberis* a Barbara Grüning b a Department of Economics, Society, Politics, University of Urbino Carlo Bo (Italy) b Department of Sociology and Social Research, University of Milan-Bicocca (Italy) Submitted: March 16, 2021 – Revised version: April 25, 2021 Accepted: May 8, 2021 – Published: May 26, 2021 Abstract Visual communication is far from new and is almost as old as the social sciences. In the last decades, the interest in the visual dimension of society as well as towards the visual as expression of local and global cultures increased to the extent that specific disciplinary approaches took root — e.g. visual anthropology and visual sociology. Nevertheless, it seems to us that whereas they are mostly engaged in collecting visual data and analyzing visual cultural products, little attention is paid to one of the original uses of visual mate- rial in ethnographic and social research, that is communicating social sciences. Depart- ing from some general questions, such as how visualizing sociological concepts, what role non-textual stimuli play in sociology, how they differentiate according to the kind of pub- lic, and how we can critically and reflexively assess the social and disciplinary implications of visualizations of empirical research, we collect in the special issues contributions from social scientists and comics artists who materially engaged in the production of social sci- ences via comics and graphic narratives. The article is divided into three parts. -

Text and Image in Translation

CLEaR, 2016, 3(2), ISSN 2453 - 7128 DOI: 10.1515/clear - 2016 - 0013 Text and Image in T ranslation Milena Yablonsky Pedagogical University of Cracow, Poland [email protected] Abstract The primary objective of the following paper is t he analysis of selected issues related to the translation of comic books. The paper aims at investigating the relationships between the text and the image and their implications in the process of translation. It reflects on the status of the translation of comics/graphic novels - a still largely unexp loited area within Translation Studies and briefly presents a definition and specificity of the genre. Moreover, it discusses Jakobson’s (1971) tripartite distinction into interlinguistic, intralinguistic and intersemiotic translation. The paper concludes with the analysis of certain issues associated with the Polish translation of V like Vendetta by Alan Moore, a text that is copious with intertextual and cultural references. Keywords: graphic novel, comics, V like Vendetta , Jakobson, constrained translat ion, intertextuality Introduction The translation of comic books still occupies a rather unexploited area within the discipline of Translation Studies, maybe due to the fact that it “might be perceived as a field of l esser interest” (Zanettin 273) and comics are usually regarded as an artistic form of a lower status. In Dictionary of Translation Studies by Shuttleworth and Cowie there is no t a single entry on comics. They refer to them only when they explain the term “multi - medial texts” ( 109 - 1 10) as: “ . The multi - medial category consists of texts in which the ver bal content is supplemented by elements in other media; however, all such texts will also simultaneously belong to one of the other, main text - type . -

The History of Web Comics Pdf Free Download

THE HISTORY OF WEB COMICS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK T. Campbell | 192 pages | 06 Jun 2006 | Antarctic Press Inc | 9780976804390 | English | San Antonio, Texas, United States The History of Web Comics PDF Book When Alexa goes to put out the fire, her clothes get burnt away, and she threatens Sam and Fuzzy with the fire extinguisher. Columbus: Ohio State U P. Stanton , Eneg and Willie in his book 'The Adventures of Sweet Gwendoline' have brought this genre to artistic heights. I would drive back and forth between Massachusetts and Connecticut in my little Acura, with roof racks so I could put boxes of shirts on top of the car. I'll split these up where I think best using a variety of industry information. Kaestle et. The Creators Issue. To learn more or opt-out, read our Cookie Policy. Authors are more accessible to their readers than before, and often provide access to works in progress or to process videos based on requests about how they create their comics. Thanks to everyone who's followed our work over the years and lent a hand in one way or another. It was very meta. First appeared in July as shown. As digital technology continues to evolve, it is difficult to predict in what direction webcomics will develop. The History of EC Comics. Based on this analysis, I argue that webcomics present a valuable archive of digital media from the early s that shows how relationships in the attention economy of the digital realm differ from those in the economy of material goods. -

Body Bags One Shot (1 Shot) Rock'n

H MAVDS IRON MAN ARMOR DIGEST collects VARIOUS, $9 H MAVDS FF SPACED CREW DIGEST collects #37-40, $9 H MMW INV. IRON MAN V. 5 HC H YOUNG X-MEN V. 1 TPB collects #2-13, $55 collects #1-5, $15 H MMW GA ALL WINNERS V. 3 HC H AVENGERS INT V. 2 K I A TPB Body Bags One Shot (1 shot) collects #9-14, $60 collects #7-13 & ANN 1, $20 JASON PEARSON The wait is over! The highly anticipated and much debated return of H MMW DAREDEVIL V. 5 HC H ULTIMATE HUMAN TPB JASON PEARSON’s signature creation is here! Mack takes a job that should be easy collects #42-53 & NBE #4, $55 collects #1-4, $16 money, but leave it to his daughter Panda to screw it all to hell. Trapped on top of a sky- H MMW GA CAP AMERICA V. 3 HC H scraper, surrounded by dozens of well-armed men aiming for the kill…and our ‘heroes’ down DD BY MILLER JANSEN V. 1 TPB to one last bullet. The most exciting BODY BAGS story ever will definitely end with a bang! collects #9-12, $60 collects #158-172 & MORE, $30 H AST X-MEN V. 2 HC H NEW XMEN MORRION ULT V. 3 TPB Rock’N’Roll (1 shot) collects #13-24 & GS #1, $35 collects #142-154, $35 story FÁBIO MOON & GABRIEL BÁ art & cover FÁBIO MOON, GABRIEL BÁ, BRUNO H MYTHOS HC H XMEN 1ST CLASS BAND O’ BROS TP D’ANGELO & KAKO Romeo and Kelsie just want to go home, but life has other plans. -

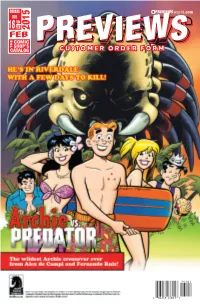

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 FEB 2015 FEB COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/8/2015 3:45:07 PM Feb15 IFC Future Dudes Ad.indd 1 1/8/2015 9:57:57 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Shield #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Sonic/Mega Man: Worlds Collide: The Complete Epic TP l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Badlands #75 l AVATAR PRESS INC Extinction Parade Volume 2: War TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Lady Mechanika: The Tablet of Destinies #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS UFOlogy #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Lumberjanes Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Masks 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Jungle Girl Season 3 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Uncanny Season 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Supermutant Magic Academy GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Rick & Morty #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Bloodshot Reborn #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC GYO 2-in-1 Deluxe Edition HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books l COMICS Taschen’s The Bronze Age Of DC Comics 1970-1984 HC l COMICS Neil Gaiman: Chu’s Day at the Beach HC l NEIL GAIMAN Darth Vader & Friends HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection Special #5: Klingon Bird-of-Prey l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #2 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man Magazine #3 l COMICS Doctor Who Special #40 l DOCTOR WHO 2 TRADING CARDS Topps 2015 Baseball Series 2 Trading Cards l TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL DC Heroes: Aquaman Navy T-Shirt l PREVIEWS EXCLUSIVE WEAR 2 DC Heroes: Harley Quinn “Cells” -

Microsoft Visual Basic

$ LIST: FAX/MODEM/E-MAIL: aug 23 2021 PREVIEWS DISK: aug 25 2021 [email protected] for News, Specials and Reorders Visit WWW.PEPCOMICS.NL PEP COMICS DUE DATE: DCD WETH. DEN OUDESTRAAT 10 FAX: 23 augustus 5706 ST HELMOND ONLINE: 23 augustus TEL +31 (0)492-472760 SHIPPING: ($) FAX +31 (0)492-472761 oktober/november #557 ********************************** __ 0079 Walking Dead Compendium TPB Vol.04 59.99 A *** DIAMOND COMIC DISTR. ******* __ 0080 [M] Walking Dead Heres Negan H/C 19.99 A ********************************** __ 0081 [M] Walking Dead Alien H/C 19.99 A __ 0082 Ess.Guide To Comic Bk Letterin S/C 16.99 A DCD SALES TOOLS page 026 __ 0083 Howtoons Tools/Mass Constructi TPB 17.99 A __ 0019 Previews October 2021 #397 5.00 D __ 0084 Howtoons Reignition TPB Vol.01 9.99 A __ 0020 Previews October 2021 Custome #397 0.25 D __ 0085 [M] Fine Print TPB Vol.01 16.99 A __ 0021 Previews Oct 2021 Custo EXTRA #397 0.50 D __ 0086 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.01 14.99 A __ 0023 Previews Oct 2021 Retai EXTRA #397 2.08 D __ 0087 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.02 14.99 A __ 0024 Game Trade Magazine #260 0.00 N __ 0088 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.03 14.99 A __ 0025 Game Trade Magazine EXTRA #260 0.58 N __ 0089 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.04 14.99 A __ 0026 Marvel Previews O EXTRA Vol.05 #16 0.00 D __ 0090 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.05 14.99 A IMAGE COMICS page 040 __ 0091 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.06 16.99 A __ 0028 [M] Friday Bk 01 First Day/Chr TPB 14.99 A __ 0092 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.07 16.99 A __ 0029 [M] Private Eye H/C DLX 49.99 A __ 0093 [M] Sunstone Book 01 H/C 39.99 A __ 0030 [M] Reckless -

Adult Comics

9780415606899.c:Layout 1 22/8/10 20:00 Page 1 ISBN 978-0-415-60689-9 90000 9 780415 606899 Adult Comics In a society where a comic equates with knockabout amusement for children, the sudden pre-eminence of adult comics, on everything from political satire to erotic fantasy, has predictably attracted an enormous amount of attention. Adult comics are part of the cultural landscape in a way that would have been unimaginable a decade ago. In this first survey of its kind, Roger Sabin traces the history of comics for older readers from the end of the nineteenth century to the present. He takes in the pioneering titles pre-First World War, the underground 'comix' of the 1960s and 1970s, 'fandom' in the 1970s and 1980s, and the boom of the 1980s and 1990s (including 'graphic novels' and Viz.). Covering comics from the United States, Europe and Japan, Adult Comics addresses such issues as the graphic novel in context, cultural overspill and the role of women. By taking a broad sweep, Sabin demonstrates that the widely-held notion that comics 'grew up' in the late 1980s is a mistaken one, largely invented by the media. Adult Comics: An Introduction is intended primarily for student use, but is written with the comic enthusiast very much in mind. Roger Sabin is a freelance arts journalist, living and working in London. He has written about comics for several national news- papers and magazines, including The Guardian, The Independent and New Statesman and Society. THE NEW ACCENT SERIES General Editor: Terence Hawkes Alternative Shakespeares 1, ed. -

Comic Books: Superheroes/Heroines, Domestic Scenes, and Animal Images

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1980 Volume II: Art, Artifacts, and Material Culture Comic Books: Superheroes/heroines, Domestic Scenes, and Animal Images Curriculum Unit 80.02.03 by Patricia Flynn The idea of developing a unit on the American Comic Book grew from the interests and suggestions of middle school students in their art classes. There is a need on the middle school level for an Art History Curriculum that will appeal to young people, and at the same time introduce them to an enduring art form. The history of the American Comic Book seems appropriately qualified to satisfy that need. Art History involves the pursuit of an understanding of man in his time through the study of visual materials. It would seem reasonable to assume that the popular comic book must contain many sources that reflect the values and concerns of the culture that has supported its development and continued growth in America since its introduction in 1934 with the publication of Famous Funnies , a group of reprinted newspaper comic strips. From my informal discussions with middle school students, three distinctive styles of comic books emerged as possible themes; the superhero and the superheroine, domestic scenes, and animal images. These themes historically repeat themselves in endless variations. The superhero/heroine in the comic book can trace its ancestry back to Greek, Roman and Nordic mythology. Ancient mythologies may be considered as a way of explaining the forces of nature to man. Examples of myths may be found world-wide that describe how the universe began, how men, animals and all living things originated, along with the world’s inanimate natural forces. -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

Apr COF C1:Customer 3/8/2012 3:24 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 18APR 2012 APR E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG IFC Darkhorse Drusilla:Layout 1 3/8/2012 12:24 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page April:gem page v18n1.qxd 3/8/2012 11:16 AM Page 1 THE MASSIVE #1 STAR WARS: KNIGHT DARK HORSE COMICS ERRANT— ESCAPE #1 (OF 5) DARK HORSE COMICS BEFORE WATCHMEN: MINUTEMEN #1 DC COMICS MARS ATTACKS #1 IDW PUBLISHING AMERICAN VAMPIRE: LORD OF NIGHTMARES #1 DC COMICS / VERTIGO PLANETOID #1 IMAGE COMICS SPAWN #220 SPIDER-MEN #1 IMAGE COMICS MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 3/8/2012 11:40 AM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Strawberry Shortcake Volume 2 #1 G APE ENTERTAINMENT The Art of Betty and Veronica HC G ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Bleeding Cool Magazine #0 G BLEEDING COOL 1 Radioactive Man: The Radioactive Repository HC G BONGO COMICS Prophecy #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Pantha #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 Power Rangers Super Samurai Volume 1: Memory Short G NBM/PAPERCUTZ Bad Medicine #1 G ONI PRESS Atomic Robo and the Flying She-Devils of the Pacific #1 G RED 5 COMICS Alien: The Illustrated Story Artist‘s Edition HC G TITAN BOOKS Alien: The Illustrated Story TP G TITAN BOOKS The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen III: Century #3: 2009 G TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Harbinger #1 G VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC Winx Club Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA BOOKS & MAGAZINES Flesk Prime HC G ART BOOKS DC Chess Figurine Collection Magazine Special #1: Batman and The Joker G COMICS Amazing Spider-Man Kit G COMICS Superman: The High Flying History of America‘s Most Enduring -

PDF Download Reinventing Comics How Imagination and Technology

REINVENTING COMICS HOW IMAGINATION AND TECHNOLOGY ARE REVOLUTIONIZING AN ART FORM 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Scott McCloud | 9780060953508 | | | | | Reinventing Comics How Imagination and Technology Are Revolutionizing an Art Form 1st edition PDF Book That said, this is a fascinating book for a number of reasons. TM: You made a point in Understanding Comics about how time equals space in comics. But there is a stunning jewel in the surrounding stone, and if you chipped away everything else the book would still be worth whatever you paid for it these days probably like a quarter for this chapter alone. We have in stock every item we list. This is a very long book, so people have time to adjust to my style. Whereas Understanding Comics was a timeless philosophical study for the sake of the art, Reinventing Comics moors itself firmly in the late 90s, exhaustively studying the history and industry of comics as it stood in the 90s and how it may shape up in the then-future. SM: I agree with you to an extent about there being a fundamental reader participation component to comics and that achieving that transparency in comics is a lot harder than it is in novels. But I was looking for a strong emotional effect. As others have noted, "Reinventing Comics" is more a product of its time and thus less timeless than McCloud's "Understanding Comics. May 09, zilby rated it it was ok Shelves: kw. That I put enough speed bumps [in] the growing complexity of those pages, that people would more naturally slow down. -

Foregrounding Narrative Production in Serial Fiction Publishing

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2017 To Start, Continue, and Conclude: Foregrounding Narrative Production in Serial Fiction Publishing Gabriel E. Romaguera University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Romaguera, Gabriel E., "To Start, Continue, and Conclude: Foregrounding Narrative Production in Serial Fiction Publishing" (2017). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 619. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/619 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TO START, CONTINUE, AND CONCLUDE: FOREGROUNDING NARRATIVE PRODUCTION IN SERIAL FICTION PUBLISHING BY GABRIEL E. ROMAGUERA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2017 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF Gabriel E. Romaguera APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Valerie Karno Carolyn Betensky Ian Reyes Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2017 Abstract This dissertation explores the author-text-reader relationship throughout the publication of works of serial fiction in different media. Following Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of authorial autonomy within the fields of cultural production, I trace the outside influence that nonauthorial agents infuse into the narrative production of the serialized. To further delve into the economic factors and media standards that encompass serial publishing, I incorporate David Hesmondhalgh’s study of market forces, originally used to supplement Bourdieu’s analysis of fields.